Early Load Dispatch

|

|

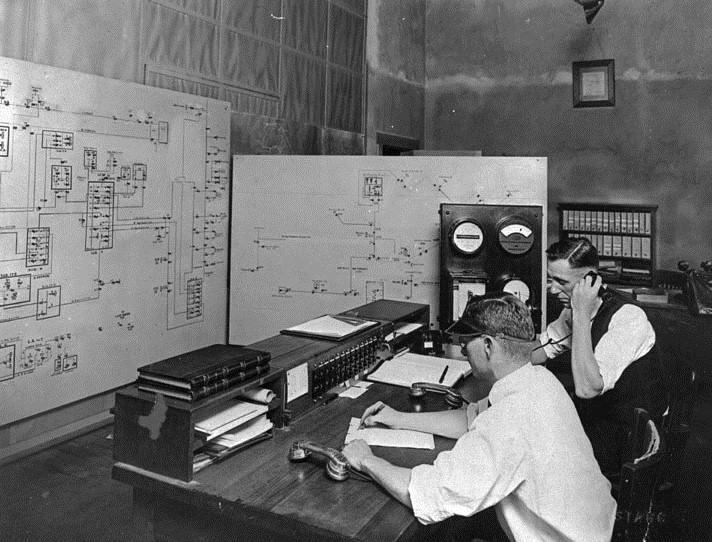

| (1925)* - The Nerve Center of the Power System is the Load Dispatcher's Office. |

LADWP Historic Archive

May, 1930 –

The Los Angeles City-owned Bureau of Power and Light is the largest City-owned and operated system in the United States. It is operated at a high rate of efficiency.

Working 24 hours a day to maintain uninterrupted service is the office of the Load Dispatcher. The prime object of the dispatcher is to see that the main high tension system is kept alive and at proper voltage and frequency for normal service.

Since 1917 when the Bureau of Power and Light went into operation, P. J. Vogel has been Chief Load Dispatcher and for many years had charge of the Main Receiving station the City as well. Under his supervision are the men who sit in front of a large chart or map which resembles a huge traffic map of a railroad system.

Continuous electrification of the Bureau’s extensive electrical system requires 24 hours of vigilance. Operation of the Power Bureau’s system involves many details of major importance, Mr. Vogel points out. These include:

The receiving and recording of the amount of water flowing in the aqueduct and the elevation and quantity of water in Fairmount Reservoir. Calculating schedules of power available from aqueduct water flowing through power houses. Determining application of power schedules at power houses with reference to time, amount, efficiency and purchased energy input schedules. Determining and dispatching machine running schedules at power plants with reference to efficiency and standby power.

The dispatcher must keep in constant touch with all parts of the electric system and see that it is kept in a normal state of operation, and that the proper complement of equipment is kept in operations to insure good service.

“We must exercise extreme caution in regard to disconnecting and taking electrical equipment out of service before workmen make repairs on transmission lines, station and other electrical apparatus,” said Mr. Vogel.

“We must handle the system during trouble, initiate communications and orders to all parts of it for the quick restoration of service.”

In other words, the Load Dispatcher has a 24-hour a day job, with plenty of action every hour.^

|

|

| (1935)* - P. J. Vogel, chief system load dispatcher, examining one of the graphs which show fluctuation in power demands on the municipal electric system. |

LADWP Historic Archive

P. J. Vogel, chief system load dispatcher, examining one of the graphs which show fluctuation in power demands on the municipal electric system

January 1936 – Los Angeles’ eating, working and sleeping habits are an open book to the Load Dispatchers of the municipal Power Bureau.

By means of graphs and curves plotted daily under the direction of P. J. Vogel, chief system load dispatcher, these and other interesting facts about Los Angeles and its citizens are recorded daily. Information is compiled by adding the total amount of energy purchased from the Edison system to the output of the Bureau’s hydro-generating plants.

Los Angeles begins to stir at five in the morning, the chart shows, with electric demand gradually increasing until about seven. From that time on the graph points sharply upward as factory motors being to turn and the city’s business swings into action.

Between nine-thirty and eleven the city is busiest, activity dropping off at noon and then climbing back until an afternoon high is reached between two and three. A possibility that the siesta of early California days is yet observed in Los Angeles is indicated by the afternoon chart tracery, which never touches the high mark of the morning.

At four-thirty Los Angeles workers begin to call it a day, the sensitive recorder shows. Electric use drops temporarily but between five thirty and six the highest demand of the entire 24 hours is registered.

This is explained as an overlapping of residential requirements, when lights are turned on for the evening, with those of business and industries that operate until around six. As these end their day, the total amount of electricity used begins a long, gradual drop until the street lights are switched off in the morning and another day starts.

It is noteworthy that at no time during the evening is there an abrupt break to signify a favored bedtime, upsetting the statement sometimes made that this is a nine o’clock town.

The effect of the five day week is noticeable in the Saturday morning peak, which is well below that of any other workday morning. It also is evident that of those business opening for the day, many close at noon. The usual drop shown at that hour climbs only slightly afterward.

Sunday is a day of rest, according to the tell-tale cart. Early risers are few and the day’s high mark is not reached until about two hours later than usual.

So far as business activity is concerned, July Fourth is the most extensively celebrated holiday, with Thanksgiving and Christmas close behind. On the Fourth, demand for electricity’s services hits the low point of the year.

Financial experts who study electric output figures as one of the important indexes of business find an interesting picture of the depression years in Los Angeles in the valleys and peaks of the Power Bureau charts. The theory that Los Angeles is the last to feel depression effects is borne out in its electric pulse.

Until 1930 the trend was steadily up. In 1931 the average showed no gain or loss. In 1932 the break came, going steadily downhill until June, 1933. So far as electric output is a business index, that marked the turning point, with a gain recorded constantly since then.

Since May, every month this year has shown more electricity being used by Los Angeles citizens than in any previous month in the entire operation of the Bureau of Power and Light.

In addition to these major features, the impassive charts continue to show that Tuesday is ironing day. That day is usually the high day of the week, and electric ironers in use by thousands of women are credited with the phenomena.^

|

|

| (1941)* - W. J. Thoman's desk shows extensive communications facilities. Others desks are identically equipped.This was the “nerve center” of the entire municipal electric system in 1941. |

|

|

| (1952)* - Power dispatchers headquarters at Boylston Street. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1968)* - Load dispatcher office at Boylston Street. |

LADWP Historic Archive

One of the most graphic pictures of the growth of the Department’s Power System over the past 15 years can be seen on the huge circular diagram board in the Load Dispatchers headquarters at 115 S. Boylston Street, which began operation in that location back in December of 1941.

There in an auditorium-like room, which is the “nerve center” of the entire municipal electric system, are displayed schematic diagrams of every line, distributing station and switch in the department’s 34,500 volt system, as well as all the Department’s high voltage transmission lines, receiving stations and generating plants, including Hoover Power Plant.

The tremendous growth of the Power System was brought into sharp focus with the completion last December 20, 1956 of a new enlarged version of the portion of the diagram board which displays the entire 34,500 volt system.

In order to accommodate the rapidly expanding system diagram, it was necessary for Department forces to increase that portion of the board from its original 60-foot length to a new length of 78 feet.

The redesigned system diagram, set up to represent normal operating conditions, was installed on a new enlarged metal board (the old one was made of wood) by use of pressure sensitive paper tape and permanent symbols which indicate switches that normally are closed and also those normally open.

When an abnormal condition, or change in the normal position of a switch occurs, it is indicated on the board by placing a magnetic symbol over the normal symbol.

Switch positions on the generation and transmission portion of the board, located on the opposite side of the room, are indicated by lights which flash automatically every time a switch is opened or closed. Red lights indicate closed switches, while green lights show open switches.

In the center of the huge circular diagram board, and separating the 34,500 volt system board area from the power generation and transmission part of the board, are the recording and indicating meters which show the total power coming into receiving stations from all the department’s generating plants, including Hoover Power Plant.

To make room for the diagram board expansion, it was necessary to relocate several of the recording meters on a new panel to the rear of the board.

A comparison between the Power System in December of 1941, when the present Load Dispatchers Headquarters started operation, and the system 15 years later in December of 1956 is probably the best way to realize the great expansion during that period, according to Chief Dispatcher Walter J. Thoman.

In December of 1941 there were five receiving stations, and by December of 1956 that number had increased to 11. During the same period, the number of distributing stations jumped from 85 to 110.

Back in December of 1941, the Department generated electric energy at the four Aqueduct hydroelectric plants, six hydro plants in the Owens Valley and at Hoover Dam Power Plant, the aggregate of which had a total generating, capacity of 469,000 kilowatts. Since 1941, an additional generating unit has been installed at the Hoover plant and the Department has built the three hydro plants of the Owens Gorge development, giving a present-day (February 1957) capability of 678,000 kilowatts for the 14 hydroelectric plants.

There were two steam plants in operation in 1941, Alameda and Seal Beach, and one unit leased from the Edison Company; there are three in operation today, Valley, Harbor and Seal Beach. The total generating capacity of steam plants in 1941 was 205,000 kilowatts, but by last December (1956) the total capacity had risen to 965,000 kilowatts.

Mr. Thoman also pointed out that the power generation peak in 1941 was 485,000 kilowatts, as compared to 1,268,000 kilowatts in 1956.

In addition to recent changes in the size of the diagram board, the Load Dispatchers Headquarters also added two more dispatchers to its force, and two new telephone desks were installed for their use.

The working stations or telephone desks of the dispatchers are located in the center of the room so that by merely rotating in their revolving chairs they can see in an instant any detail on the circular control board which is essential to the accurate performance of their work.

What are the duties of the highly trained personnel in the Dispatchers Headquarters?

Their prime function is to see that there always is enough electric energy flowing through the Power System to meet all of the demands of the Department’s more than 829,000 customers.

Acting with the utmost speed and accuracy at all times, dispatchers are solely responsible for giving the bulk of the switching orders through the system by means of the network of telephone and radio facilities at their fingertips.

Another important function is the preparation, usually several days in advance, of load schedules for the various generating plants.

An around-the-clock operation 365 days a year, load dispatching is handled by three shifts of men who are on duty continuously during their working periods.^

References

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

^LADWP Historic Archive

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Mulholland Service Award

- Major Efforts

- Board Officers and Directors

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index