Early Views of the San Fernando Mission

Foundations and Founding of the Mission 1769–1797

|

|

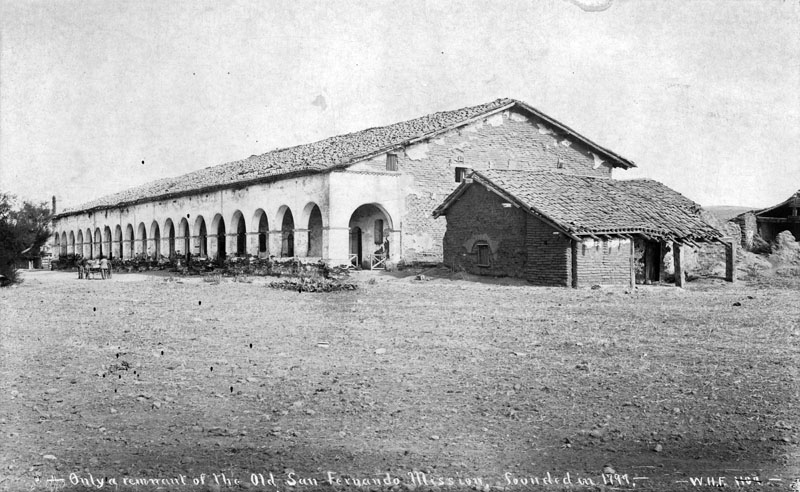

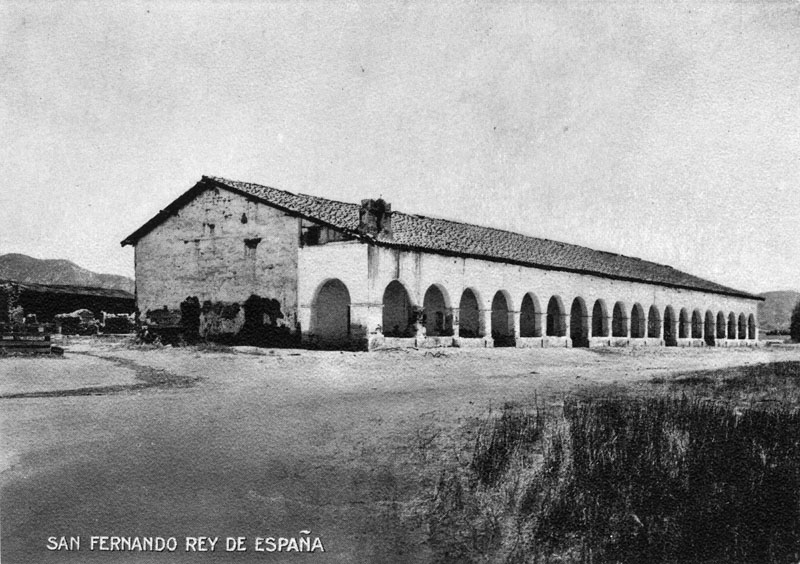

| (ca. 1900)* - Postcard view of Mission San Fernando Rey de España. |

Historical Notes The San Fernando Valley was first entered by the Portola expedition in 1769, but no permanent settlement was established at that time. Spanish authorities later sought to expand the mission system to close long gaps along El Camino Real between San Gabriel and San Buenaventura. In the late 1790s, Father Fermín Lasuén, who succeeded Father Junípero Serra as head of the California missions, approved the San Fernando Valley as the site for a new mission. The location offered good water, open land for farming and grazing, and a strategic stop along the inland route. A brief note of historical context: like other California missions, Mission San Fernando operated within a colonial system that brought significant disruption to Indigenous life. Many Indigenous people were drawn or compelled into mission labor and religious instruction. The mission era brought lasting cultural loss and hardship alongside the physical development recorded in these images. The land had been used by Francisco Reyes, the first mayor of the Los Angeles pueblo, who raised cattle there. Accounts differ on how formal his claim was, but he gave up use of the land when the mission was approved. Mission San Fernando Rey de España was founded on September 8, 1797, and named for Saint Ferdinand III, King of Spain. On the day of its founding, records indicate that five Indigenous boys and five Indigenous girls were baptized. Francisco Reyes served as a patron of the dedication and as godfather to the first child baptized. |

|

|

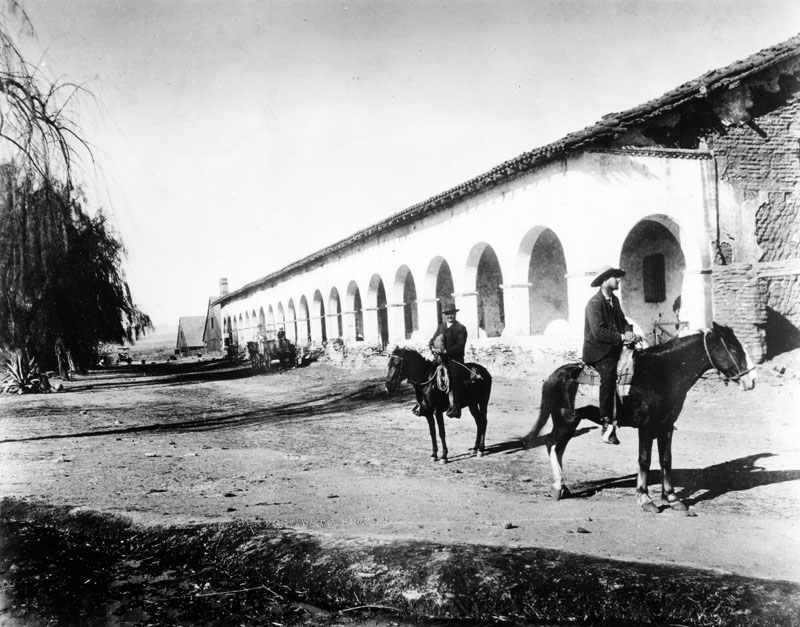

| (ca. 1870)* - Exterior view of Mission San Fernando showing the adobe cloister at right and additional mission buildings at left. Dirt paths converge in the foreground, and portions of the tiled roof have collapsed. |

Historical Notes This photograph shows the mission complex many decades after its founding, following years of earthquakes, neglect, and changing ownership. The image is often mistaken as an early mission era view, but it actually reflects the mission after secularization and decline. The original mission buildings were constructed of adobe and expanded over time. Roof collapse, missing plaster, and altered structures visible here reflect damage from earthquakes and the lack of sustained maintenance during the mid-1800s. |

* * * * * |

Section Guide

Use this guide to jump to the major parts of this page.

Tip: If you only have a few minutes, jump to Sections 5, 10, 17, 22, and 23 for the strongest visual timeline.

1. Foundations and Founding of the Mission (1769–1797)

2. The Mission Buildings and the Convento Long Building

3. Earthquakes, Damage, and Ruin (1812 and After)

4. Decline, Secularization, and Rancho Use (1820s–1870s)

5. The First Photographs of the San Fernando Valley (1873–1875)

6. Mission Life and the Mission Grounds (1880s)

7. The Mission in Ruins (1880s)

8. Preservation Sparks: Lummis and the Landmarks Club (1887–1903)

9. The Convento, Cloister, and Mission Grounds (1880s–1909)

10. Late-1800s Views and the Road to Restoration (1880s–1909)

11. Mission Grounds, Orchards, and Setting (1887–1890s)

12. The Convento and Cloister as Daily Space (1890s)

13. Architectural Detail and Interior Views (1898–1900)

14. Ownership, Adaptation, and Mission Uses (Late 1800s–1900)

15. Early Preservation and Restoration Begins (1903–1909)

16. Water, Brand Park, and the Mission Landscape (Early 1900s)

17. From Historic Ruin to Public Landmark (1920s)

18. Restoration Era and the Mission Returns as a Working Church (1920s–early 1930s)

19. Brand Park, Memory Garden, and the Mission Grounds (1920s)

20. Restoration Work and the Mission Landscape (Late 1920s–1930s)

21. Mission Life, Architecture, and Public Presence (1930s–1940s)

22. Later Views, Official Recognition, and Enduring Legacy (1950s–Present)

23. Context and Wrap-Up: Then & Now and the California Missions Map

Section Guide

Use this guide to jump to the major parts of this page.

Tip: If you only have a few minutes, jump to Sections 5, 10, 17, 22, and 23 for the strongest visual timeline.

1. Foundations and Founding of the Mission (1769–1797)

2. The Mission Buildings and the Convento Long Building

3. Earthquakes, Damage, and Ruin (1812 and After)

4. Decline, Secularization, and Rancho Use (1820s–1870s)

5. The First Photographs of the San Fernando Valley (1873–1875)

6. Mission Life and the Mission Grounds (1880s)

7. The Mission in Ruins (1880s)

8. Preservation Sparks: Lummis and the Landmarks Club (1887–1903)

9. The Convento, Cloister, and Mission Grounds (1880s–1909)

10. Late-1800s Views and the Road to Restoration (1880s–1909)

11. Mission Grounds, Orchards, and Setting (1887–1890s)

12. The Convento and Cloister as Daily Space (1890s)

13. Architectural Detail and Interior Views (1898–1900)

14. Ownership, Adaptation, and Mission Uses (Late 1800s–1900)

15. Early Preservation and Restoration Begins (1903–1909)

16. Water, Brand Park, and the Mission Landscape (Early 1900s)

17. From Historic Ruin to Public Landmark (1920s)

18. Restoration Era and the Mission Returns as a Working Church (1920s–early 1930s)

19. Brand Park, Memory Garden, and the Mission Grounds (1920s)

20. Restoration Work and the Mission Landscape (Late 1920s–1930s)

21. Mission Life, Architecture, and Public Presence (1930s–1940s)

22. Later Views, Official Recognition, and Enduring Legacy (1950s–Present)

23. Context and Wrap-Up: Then & Now and the California Missions Map

Section Guide

Use this guide to jump to the major parts of this page.

Tip: If you only have a few minutes, jump to Sections 5, 10, 17, 22, and 23 for the strongest visual timeline.

1. Foundations and Founding of the Mission (1769–1797)

2. The Mission Buildings and the Convento Long Building

3. Earthquakes, Damage, and Ruin (1812 and After)

4. Decline, Secularization, and Rancho Use (1820s–1870s)

5. The First Photographs of the San Fernando Valley (1873–1875)

6. Mission Life and the Mission Grounds (1880s)

7. The Mission in Ruins (1880s)

8. Preservation Sparks: Lummis and the Landmarks Club (1887–1903)

9. The Convento, Cloister, and Mission Grounds (1880s–1909)

10. Late-1800s Views and the Road to Restoration (1880s–1909)

11. Mission Grounds, Orchards, and Setting (1887–1890s)

12. The Convento and Cloister as Daily Space (1890s)

13. Architectural Detail and Interior Views (1898–1900)

14. Ownership, Adaptation, and Mission Uses (Late 1800s–1900)

15. Early Preservation and Restoration Begins (1903–1909)

16. Water, Brand Park, and the Mission Landscape (Early 1900s)

17. From Historic Ruin to Public Landmark (1920s)

18. Restoration Era and the Mission Returns as a Working Church (1920s–early 1930s)

19. Brand Park, Memory Garden, and the Mission Grounds (1920s)

20. Restoration Work and the Mission Landscape (Late 1920s–1930s)

21. Mission Life, Architecture, and Public Presence (1930s–1940s)

22. Later Views, Official Recognition, and Enduring Legacy (1950s–Present)

23. Context and Wrap-Up: Then & Now and the California Missions Map

* * * * * |

The Mission Buildings and the Convento Long Building |

This section focuses on the physical layout of Mission San Fernando Rey de España and the development of its principal structures. Particular attention is given to the convento, or “Long Building,” which became one of the most prominent and enduring features of the mission complex. |

|

|

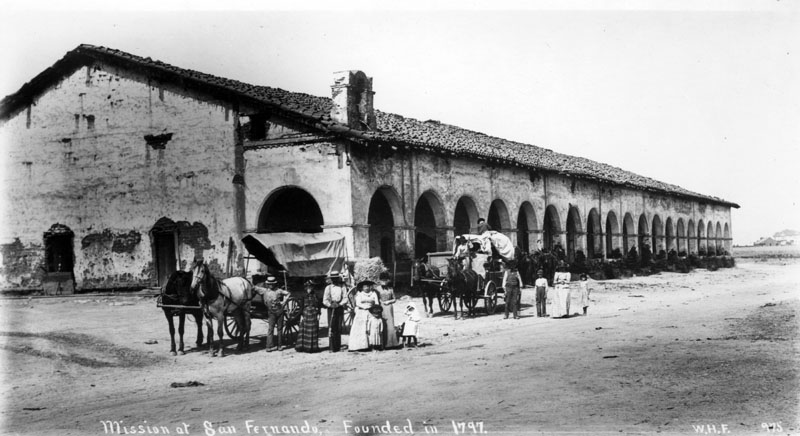

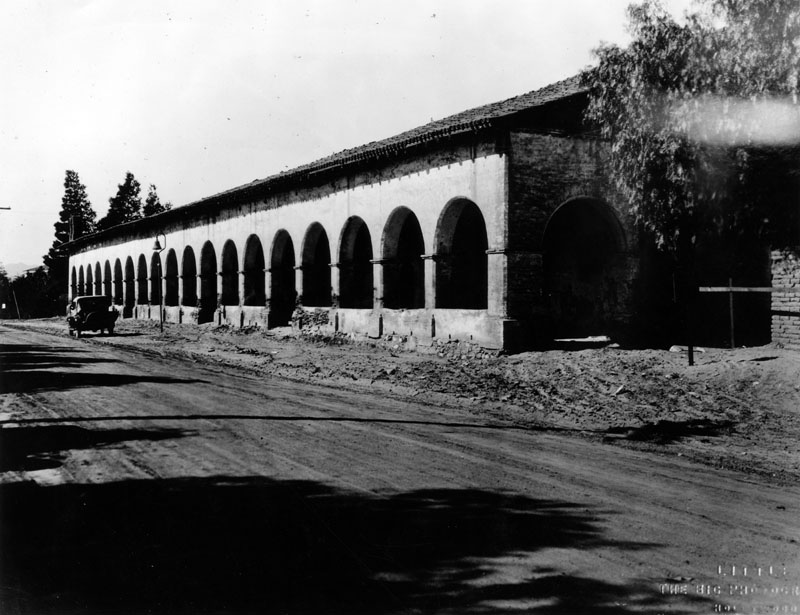

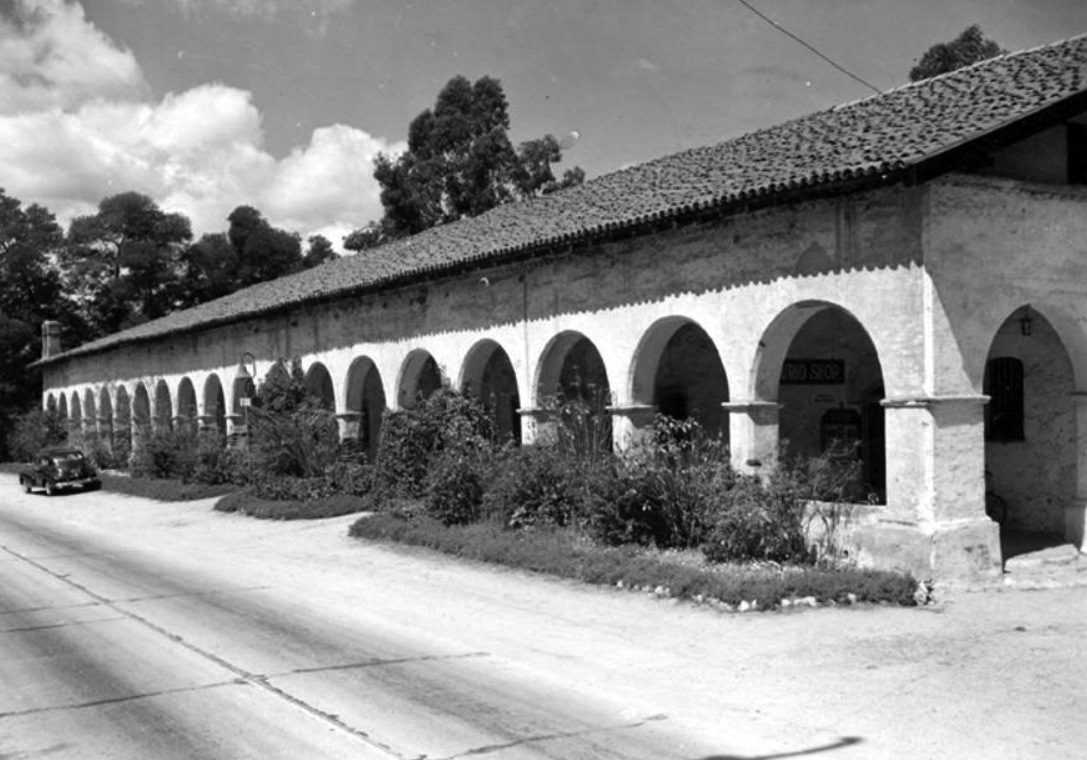

| (1800s)* - View of the convento wing known as the Long Building, with families and horse-drawn carriages stopped along the road that later became part of El Camino Real. |

Historical Notes Mission San Fernando Rey de España was the seventeenth mission established in Alta California. Like other missions, it was built around a quadrangle, with the church forming one side and living and working spaces arranged around a central courtyard. The original church built in 1797 soon became too small. A second chapel was replaced by a larger third church completed in 1806. That structure was heavily damaged by the 1812 earthquake, leading to another rebuilding completed in 1818. By the early 1800s, the mission supported a large Indigenous population. By 1804, mission records suggest that nearly one thousand Indigenous people lived and worked at San Fernando. They raised cattle and produced hides, tallow, leather goods, and cloth. Because of its location near Los Angeles and along a major travel route, the mission became a frequent stop for travelers. The fathers continually extended the convento wing to provide lodging, giving rise to its nickname, the Long Building, one of the longest adobe structures in California. |

* * * * * |

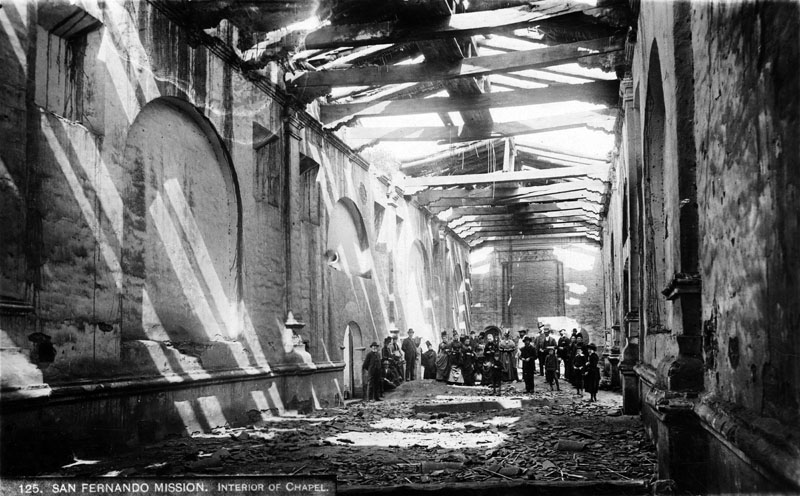

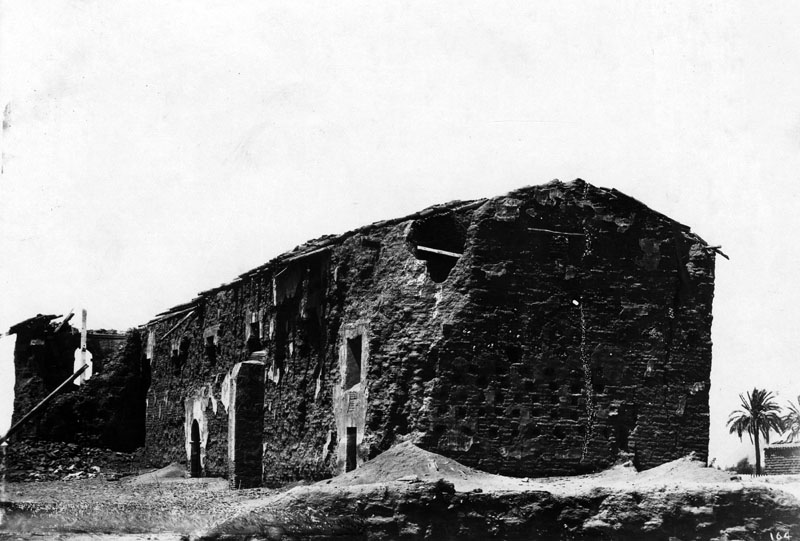

Earthquakes, Damage, and Ruin 1812 and After

The 1812 earthquake caused severe damage to Mission San Fernando, destroying much of the church and adjoining structures. Limited labor and resources delayed repairs, and several buildings were left in ruin for many years. Later earthquakes and long periods of neglect compounded the damage. Most surviving photographs show the mission decades after the initial destruction, documenting the long aftermath rather than the event itself. |

|

|

| (ca. 1860s)* - Interior view of the adobe chapel after the 1812 earthquake. Rubble covers the floor, and sunlight enters through the collapsed roof. |

|

|

| (mid-1800s)* - View of the rear portion of the original chapel and bell tower at Mission San Fernando, showing extensive deterioration following decades of earthquake damage and neglect. |

|

|

| (mid to late 1800s)* - View of the south side of the original chapel at Mission San Fernando, with crumbling adobe walls and partial structural collapse caused by long-term earthquake damage. |

|

|

| (ca. 1857)* - Mission San Fernando Rey de España in disrepair. The scene reflects decades of damage following the 1812 earthquake and later neglect. |

* * * * * |

Decline, Secularization, and Rancho Use 1820s–1870s

By the early 1800s, Mission San Fernando was entering a period of gradual decline as political changes, labor shortages, and shifting land policies began to reshape its role in the San Fernando Valley. |

|

|

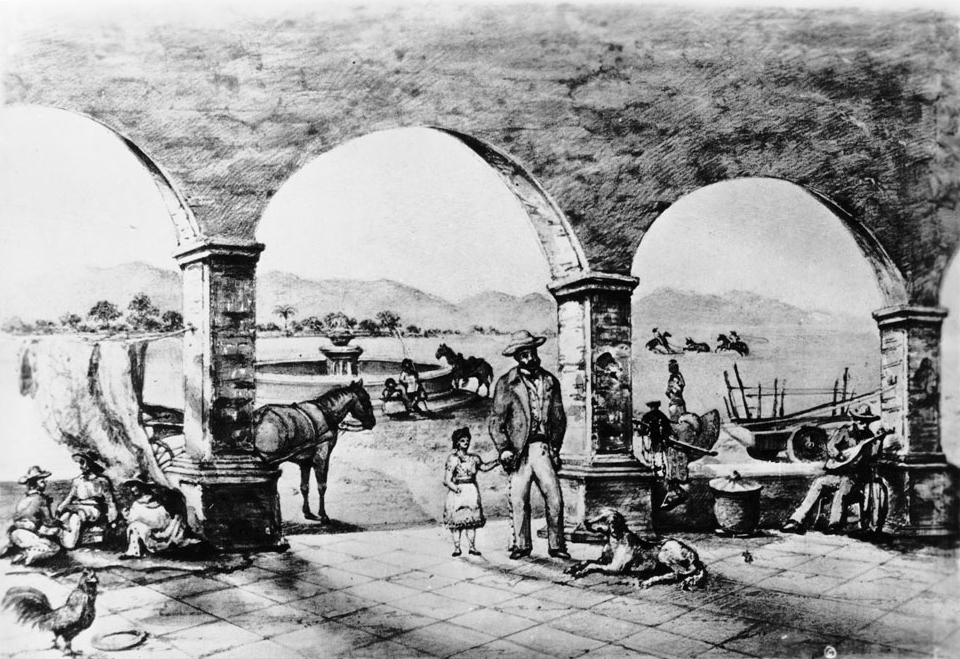

| (ca. 1865)* - Drawing by Edward Vischer showing General Andrés Pico with two Indigenous people at Mission San Fernando, looking west, 1865. |

|

|

| (1865)* - Photograph of Edward Vischer’s 1865 drawing showing General Andrés Pico under the mission arches, with everyday rancho activity nearby—figures gathered in the corridor, a carriage and fountain beyond, and vaqueros working cattle in the distance. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1870)* - Photograph of an exterior view of the Mission San Fernando. The two-story main building of the mission is pictured to the left, having lost most of its plaster. A cloister extends out from it to the right, and features a terracotta-tiled roof that has collapsed inward in spots, the entire eave gone to the extreme right. A stretch of short, dry grass stands in the foreground. |

| Historical Notes

Starting in the 1830s, California officials began confiscating mission lands, although they usually left the buildings under church control. From 1834 to 1836, many Indigenous people remained at the mission. Others looked for work in Los Angeles or joined relatives and friends who were still living freely in the nearby hills. In 1835, Father Ibarra left because he could not tolerate the secularization. As mission authority weakened, the property increasingly functioned as rancho land, and the buildings slipped into long-term neglect. The photographs that follow (1873–1875) show the mission no longer as an active religious center, but as a solitary landmark in a wide, largely undeveloped San Fernando Valley. |

* * * * * |

The First Photographs of the San Fernando Valley 1873–1875 |

Photography arrived in the San Fernando Valley at a time when the land was still largely undeveloped. Early photographs from the 1870s show Mission San Fernando standing alone in a wide, open landscape, with few signs of settlement beyond the mission buildings. These images form the first visual record of the valley and present the mission as a geographic landmark rather than an active religious center. |

|

|

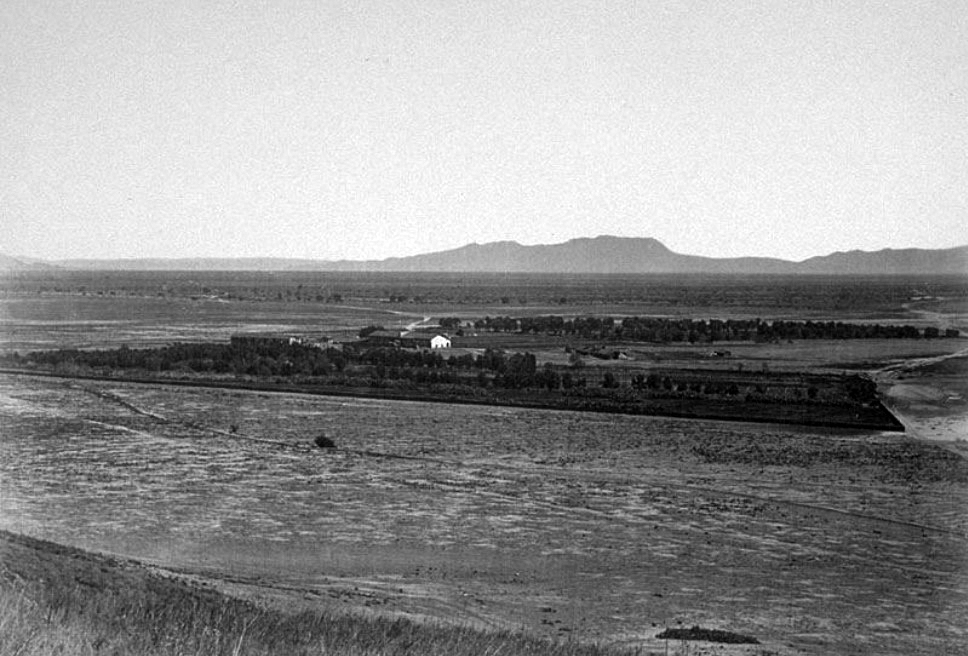

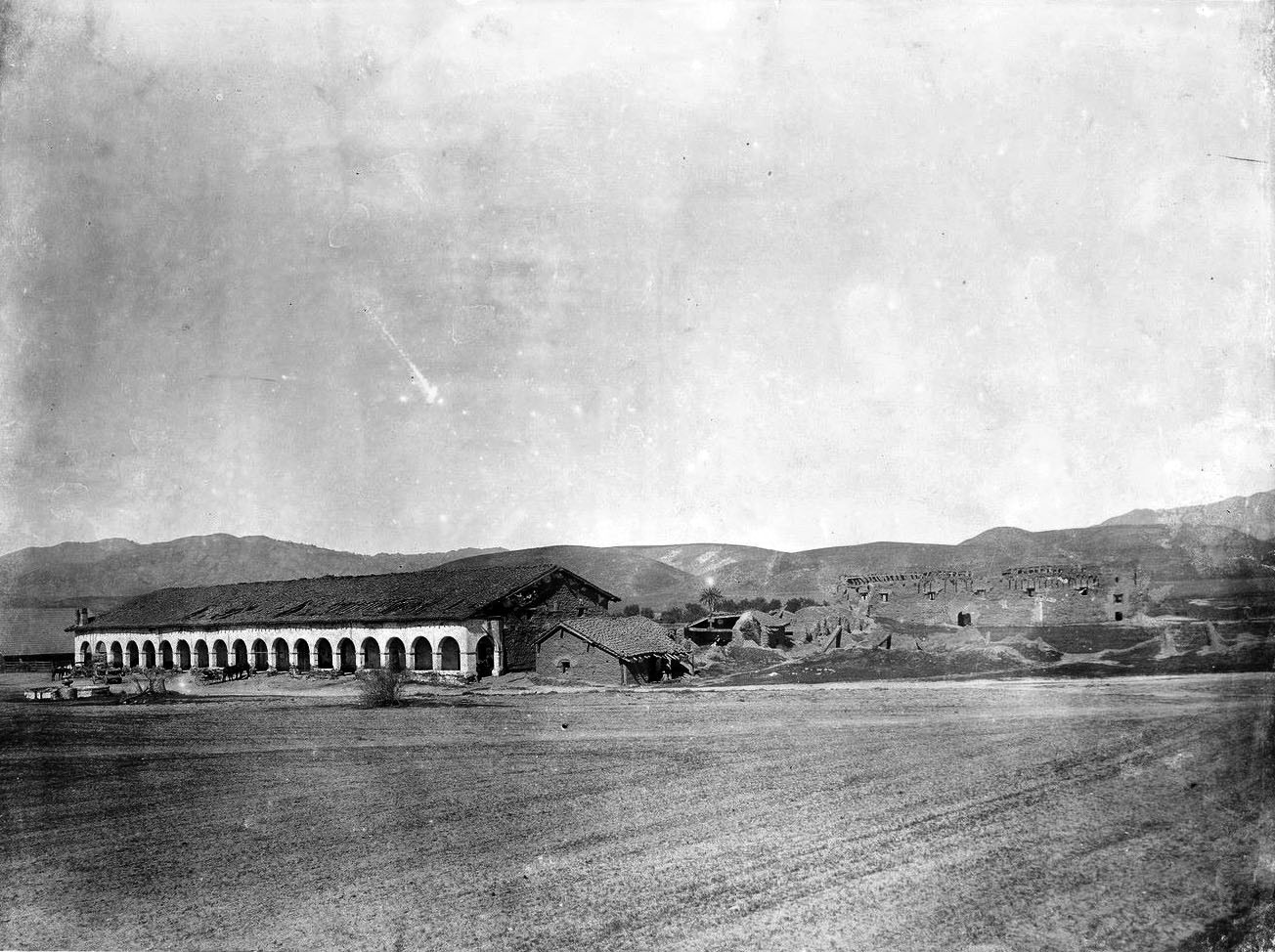

| (1873)* - First known photograph of the San Fernando Valley, looking southeast. Mission San Fernando Rey de España stands at center, surrounded by open land with no visible development. |

|

|

| (1873)* – Panoramic view of Mission San Fernando looking southeast across a largely unimproved San Fernando Valley. In the distance are the Hollywood Hills, including Cahuenga Pass and the back of Mount Lee. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1875)* - Exterior view of Mission San Fernando Rey de España ruins, photographed before 1875. A two-story adobe building rises behind crumbling walls and collapsed patios in the foreground. |

|

|

| (ca. 1875)* - View of the ruined front of the church and bell tower at Mission San Fernando. Stucco has fallen from the adobe walls, and a partially roofed patio supported by columns remains in poor condition. |

* * * * * |

Mission Life and the Mission Grounds 1880s |

Although the mission buildings continued to deteriorate during the 1880s, daily life around the grounds did not disappear. Indigenous residents and local workers remained in the area, tending crops and living near the former mission structures. These photographs offer rare glimpses of people still connected to the mission landscape during a period of transition and neglect. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1880)* – View showing an Indigenous woman tending crops near Mission San Fernando. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1880)* - Two Indigenous women seated on a wooden bench in front of a building at Mission San Fernando. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1880)* – Close-up view of an Indigenous woman standing near the mission buildings. |

* * * * * |

The Mission in Ruins 1880s

By the 1880s, much of Mission San Fernando lay in ruins. Roofs had collapsed, adobe walls crumbled, and entire structures were reduced to remnants. Photographs from this period document the mission’s physical decline just before organized preservation efforts began. |

|

|

| (ca. 1884)* - Distant view of the original chapel prior to being reroofed by the Landmarks Club. Several surrounding structures appear in advanced stages of collapse. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1884)* - View of the original chapel showing a single long crumbling wall as the last trace of an adjacent structure. |

|

|

| (ca. 1884)* - Another view of the original chapel prior to restoration, emphasizing the extent of roof loss and wall deterioration. |

|

|

| (ca. 1880s)* - View of the mission cloister and fountain in disrepair. Sections of the tiled roof are missing, and weeds have overtaken the fountain basin. |

|

|

| (ca. 1886)* - View of the two tall palm trees at Mission San Fernando with a horse and carriage nearby. Portions of the mission arcade are visible in the background. |

|

|

| (1887)* - Wide view of Mission San Fernando ruins seen from a hayfield. Roofless adobe buildings, collapsed walls, and overgrown grass illustrate the mission’s deteriorated condition. |

* * * * * |

Preservation Sparks: Lummis and the Landmarks Club 1887–1903 |

As the mission continued to deteriorate, interest in preserving California’s historic landmarks began to grow. By the late 1880s, writers, historians, and preservation advocates called attention to the condition of Mission San Fernando. These early efforts helped spark the movement that eventually led to restoration and rebuilding. |

|

|

| (ca. 1887)* - View of the original chapel and surrounding adobe structures in a state of ruin. The church roof is completely gone, and rubble fills the foreground. |

Historical Notes By the mid 1890s, Charles Fletcher Lummis emerged as a leading advocate for preserving California’s historic missions. In 1896, as president of the Landmarks Club of Southern California, Lummis began efforts to reclaim and protect Mission San Fernando. Lummis warned that the mission buildings were rapidly deteriorating, with roofs breached or gone and adobe walls dissolving under winter rains. He argued that without immediate action, little would remain of the missions beyond scattered heaps of adobe. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - Interior view of Mission San Fernando ruins looking west toward the main entrance. Exposed beams and rafters open to the sky, with vegetation growing across the dirt floor. |

* * * * * |

Decades of neglect left much of Mission San Fernando in ruins, yet parts of the site continued to function as working spaces well into the late 1800s. While the church and many adjoining buildings deteriorated, the convento, cloister, and surrounding grounds remained active, shaped by travel, agriculture, and changing uses. Photographs from this period reveal a mission site that was both worn and lived in, standing between abandonment and preservation. |

The Convento, Cloister, and Mission Grounds 1880s–1909 |

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the convento, cloister, and surrounding grounds remained the most active parts of Mission San Fernando. Photographs from this period show the mission as a working landscape, shaped as much by use and adaptation as by neglect. This section shifts attention away from collapse and toward how the mission functioned as a lived-in and adaptable space. |

|

|

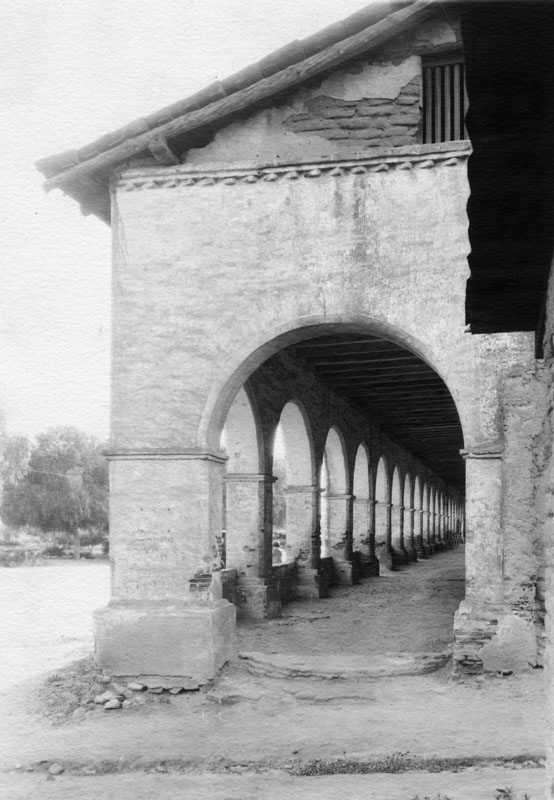

| (1800s)* - View of the convento colonnade at Mission San Fernando, showing arches, beams, and shadows along the corridor floor. |

Historical Notes By the mid-1800s, the mission grounds were no longer used for religious purposes, but parts of the site remained active. Traffic along the road in front of the convento reflects the mission’s continued role as a landmark and stopping place in the San Fernando Valley. The convento building was constructed in stages between 1808 and 1822 and measures approximately 243 feet long and 50 feet wide. Its broad portico runs the full length of the building and features thick adobe walls, exposed rafters, and a roof of fired clay tile. The long portico, often referred to as the colonnade, includes twenty-one Roman arches and is one of the most recognizable features of the mission. The convento remains the largest original adobe structure in California and the largest surviving building among the California missions. In 1842, gold was discovered on a nearby ranch, sparking a brief rush of prospectors. Rumors that missionaries had hidden gold beneath the church floors led treasure seekers to dig inside mission buildings. This activity continued sporadically into the early 1900s and contributed to further damage. |

|

|

| (ca. 1880s)* - View of activity in front of the convento building, with riders and a carriage along the road that later became El Camino Real. |

|

|

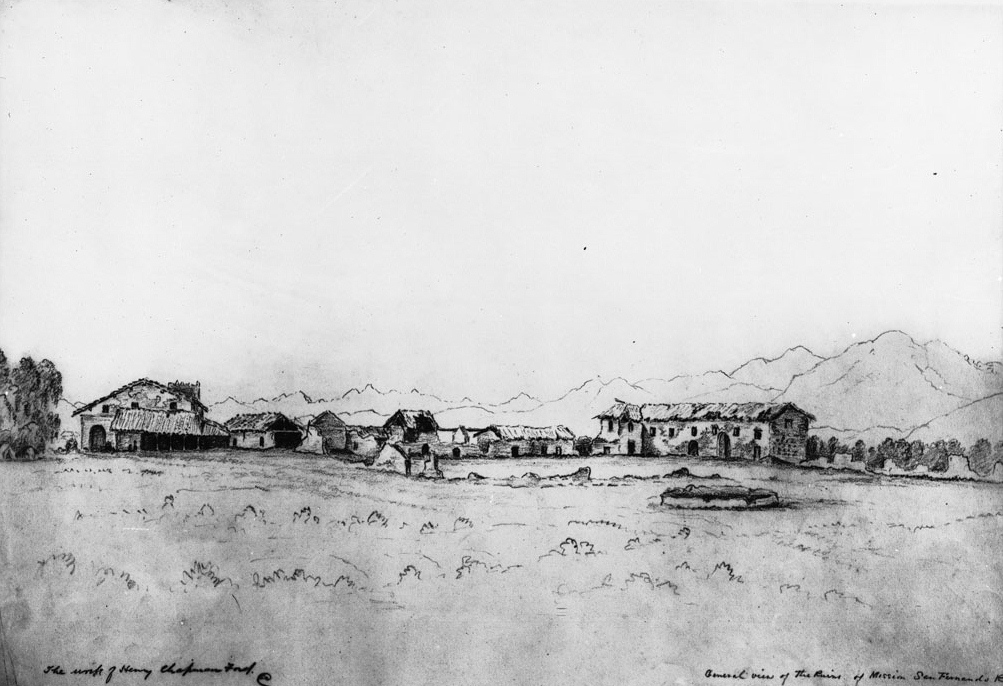

| (ca. 1883)* - Photograph of a drawing by Henry Chapman Ford showing Mission San Fernando Rey de España in disrepair. The mission buildings appear in a long line across the horizon, with the tallest two-story adobe building at left and the extended convento wing at far right. A well stands in the foreground, with mountains in the distance. |

|

|

| (1883)* - View of the convento building, also known as the Long Building, with an adjacent smaller structure as they appeared in 1883. |

|

|

| (1883)* - Postcard view of Mission San Fernando Rey de España showing the convento and surrounding mission grounds. |

|

|

| (ca. 1884)* - View of the gardener’s adobe at Mission San Fernando. The small adobe house shows exposed timbers beneath a tile roof and is enclosed by a rough picket fence. Chickens stand in the yard in front. |

Historical Notes After abandonment in 1847, mission buildings were adapted for various uses. Between 1857 and 1861, part of the site served as a stagecoach station. By the late 1800s, sections of the mission were used for storage, stables, and livestock. In 1896, Charles Fletcher Lummis began efforts to reclaim and protect the mission property, marking the beginning of improved conditions and eventual restoration. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1886)* - View from within the mission corridor looking outward across the grounds. Wooden beams support the roof above large adobe arches. A fountain stands outside the corridor, while portions of ruined walls are visible in the distance. |

|

|

| (ca. 1886)* - Exterior view of the mission cloister with a pepper tree in the foreground. Dry grass and brush surround the structure, reflecting the worn condition of the mission grounds during this period. |

* * * * * |

Late-1800s Views and the Road to Restoration 1880s–1909 |

By the late 1800s, Mission San Fernando existed in a transitional state. While many structures remained in disrepair, the site continued to function as farmland, landmark, gathering place, and historic curiosity. Photographs from this period document both decline and the earliest steps toward preservation. While earlier images emphasize physical ruin, the views that follow focus on continued use and the first stirrings of organized preservation. |

Mission Grounds, Orchards, and Setting 1887–1890s

|

|

| (ca. 1887)* - Photograph of cultivated field with a few scattered palm and olive trees, with Mission San Fernando Rey de España in the distance. A long row of white arches dominates the view, with mountains in the background. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - Photograph of the Mission San Fernando Rey de España viewed from an olive orchard. Two lush olive trees frame the foreground, with a withered tree between them. A brick wall separates the orchard from the mission grounds. The mission church appears in the center background, a two-story adobe with an arched doorway and a rectangular window above. A post-and-rail fence runs along its side. |

|

|

| (1890s)* - View of Mission San Fernando Rey de España showing the cloister, old gardener’s adobe, and ruins of the original chapel. Photo by A. C. Vroman. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1890s)* – View looking north showing Mission San Fernando behind mature palm trees. Photo by A. C. Vroman. |

|

|

| (1890)* - View of the Convento Building, also known as the “Long Building,” with palm and olive trees planted by the padres. Four people dressed in dark clothing stand at the base of the left palm. |

Historical Notes The Convento Building was, and remains, the largest adobe structure in California and the largest original building among California’s missions. |

|

|

| (1896)^# - “The Palms of San Fernando,” from the December 1896 issue of The Land of Sunshine. The illustration accompanies an article on the San Fernando Mission ruins, with the monastery visible in the background. |

Historical Notes California’s eighteenth-century Franciscan missionaries were among the first to plant palms ornamentally, likely for their biblical symbolism. Despite their early presence at missions, palms were not widely embraced as landscape features until Southern California’s turn-of-the-twentieth-century gardening boom. Despite the many palm species seen in Los Angeles today, only one — Washingtonia filifera, the California fan palm — is indigenous to the state. All other palms commonly associated with Southern California landscapes were introduced from elsewhere and planted primarily for decorative purposes. |

|

|

| (1898)* - Exterior view of the Mission San Fernando cloister. The long, one-story building is shown broadside, with evenly spaced arches forming the colonnade. Tall weed-like plants, identified on the file card as “sunflowers,” grow in the foreground amid sedgegrass. |

* * * * * |

The Convento and Cloister as Daily Space (1890s) |

During the 1890s, the convento and cloister functioned as the most usable and occupied areas of Mission San Fernando. While much of the mission complex lay in ruins, these covered corridors and adjacent spaces continued to serve daily needs related to travel, work, and social gathering. Photographs from this period show people using the mission not as a religious center, but as a lived-in and practical environment. |

|

|

| (1899)* - Horse-drawn wagon in front of the San Fernando Mission. Photo courtesy of the Altadena Historical Society |

| Historical Notes

By the late 1800s, the convento and cloister remained the most functional parts of Mission San Fernando. Their covered corridors provided shelter, storage, and gathering space at a time when much of the mission complex was deteriorating. Traffic along the adjacent road and the presence of wagons, riders, and visitors reflect the mission’s continued role as a stopping place and local landmark rather than an active religious center. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1899)* - A group of people pose for the camera in front of the “Long Building” at the San Fernando Mission. Photo courtesy of the Altadena Historical Society |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - Exterior view of Mission San Fernando Rey de España from the west end of the cloister. The cloister and building appear in dilapidated condition, with several people standing beneath the arches. |

|

|

| (Late 1800s)* - View of the convento colonnade, or archway, of Mission San Fernando Rey de España Mission, showing the length of the corridor, arches, and wood beams. |

* * * * * |

Architectural Detail and Interior Views (1898–1900)

During the late 1890s and around 1900, photographers increasingly turned their attention inward, documenting the mission’s architectural details, interior spaces, and signs of long-term deterioration. These images capture light, shadow, texture, and structural relationships within the church, workshops, and adjoining buildings, offering a closer look at how the mission’s fabric endured even as its original functions faded from daily use.

|

|

| (1898)* - Photograph looking through the south door of the ruins of the church at Mission San Fernando Rey de España. Part of two ruined buildings are visible through the opening. Striped shadows fall across the walls and dirt floor, emphasizing the exposed interior structure. |

| Historical Notes

By the end of the 19th century, much of Mission San Fernando’s church and auxiliary buildings stood roofless or partially collapsed. Interior views from this period reveal exposed beams, fallen plaster, and eroded adobe walls, while carefully framed doorways and arches continue to emphasize the mission’s original design and craftsmanship. Together, these images document a site caught between ruin and survival, preserving architectural forms even as materials slowly returned to the landscape. |

|

|

| (ca. 1898)* - View of the olive mill at the San Fernando Mission, California. A long wooden post extends from the large stone wheel, with a building visible in the background among surrounding foliage. |

|

|

| (1900)* - Partial view of the original chapel of Mission San Fernando Rey de España, which appears largely intact, alongside a crumbling adobe wall. The photograph was taken from inside another structure, with an arched opening framing the view. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* - View of the ruins of mission workshops, photographed from the church looking toward the cloister. The cloister remains roofed, though much of its stucco has fallen away, while the workshop structures in the foreground are completely roofless. |

* * * * * |

Ownership, Adaptation, and Mission Uses (Late 1800s–1900) |

After secularization, Mission San Fernando entered a long period of private ownership and adaptive use. While many mission structures deteriorated, others were repurposed for agriculture, storage, travel, and social activity. Photographs from the late 1800s reflect a site shaped less by religious life than by practical reuse, standing between abandonment and the first stirrings of preservation. |

|

|

| (1900)* - Partial view of the original chapel of Mission San Fernando Rey de España, which appears largely intact, alongside a crumbling adobe wall. The surrounding area appears deserted. Information on the verso reads: “Isaac N. Van Nuys ranch house, circa 1882. His son, J. Benton, was a member of the Executive Committee of Security First National Bank.” It is unclear which structure was Van Nuys’ ranch house. |

Historical Notes In 1845, Governor Pío Pico declared the mission buildings for sale and, in 1846, made Mission San Fernando Rey de España his headquarters as Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando. During the late 19th century, the mission complex served a variety of non-religious purposes. North of the mission stood Lopez Station, a stop on the Butterfield Stage Lines. Other structures were used as warehouses for the Porter Land and Water Company, and in 1896 the mission quadrangle was reportedly used as a hog farm. The mission church did not return to active religious use until 1923, when the Oblate priests arrived. |

|

|

| (1897)^* - The Convento Building at Mission San Fernando Rey de España as it appeared in 1897. Timber roof supports are visible. Donor: Milt Fries. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* - View of the cloister at Mission San Fernando looking west. The colonnade appears at left, with arched doorways to the monks’ former quarters at right, each flanked by barred windows. Stored materials are visible at the end of the corridor, while a dirt path winds through grass just beyond the arches. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* – Photograph titled “The Club and Friends,” showing six men seated on benches beneath the shade of the convento colonnade. Photo by A. C. Vroman. |

* * * * * |

Early Preservation and Restoration Begins (1903–1909) |

In the early 1900s, Mission San Fernando entered the first phase of organized preservation. These efforts focused primarily on stabilizing the convento, or “Long Building,” rather than fully restoring the mission complex. While some repairs were made, much of the site remained in a fragile and unfinished state, reflecting the limited resources and evolving preservation philosophy of the time. |

|

|

| (ca. 1903)* - View of the convento colonnade, or archway, of Mission San Fernando Rey de España, showing the long corridor of arches and exposed wood beams prior to restoration. |

|

|

| (ca. 1903)* - Early view of the Convento Building, also known as the “Long Building,” as it appeared in the early 1900s. The dirt road running alongside the structure is largely barren, with only a fountain and small tree visible in the distance. This road would later become El Camino Real. |

|

|

| (ca. 1903)* - View of the Convento Building after its 1903 restoration, with the original chapel structure visible at right in a continued state of ruin. The contrast highlights the selective nature of early preservation efforts. |

| Historical Notes

In 1903, preservation work began at Mission San Fernando with an emphasis on stabilizing the convento, the largest remaining structure. These early efforts did not attempt a full historical restoration but instead focused on preventing further collapse. Other mission buildings, including the original chapel, remained largely unrestored for decades, underscoring the piecemeal approach to preservation during this period. |

|

|

| (1904)* - View of the mission cloister from the southeast, showing a long row of arches supporting the exterior corridor. Portions of the tile roof have collapsed at the far end of the building, reflecting the incomplete nature of early repairs. |

|

|

| (1909)* - Distant view of Mission San Fernando with rolling hills in the background, showing the site in a more stable but still largely unrefined condition at the close of the decade. |

* * * * * |

Water, Brand Park, and the Mission Landscape (Early 1900s) |

Water shaped every aspect of Mission San Fernando’s survival and daily operation. Springs, irrigation channels, fountains, and reservoirs supported agriculture, domestic life, and industry, while the surrounding landscape evolved as mission lands transitioned into civic and public use. Photographs and maps from the early 1900s document this interconnected system of water, land, and structures at a moment when the mission’s physical footprint was beginning to stabilize. |

|

|

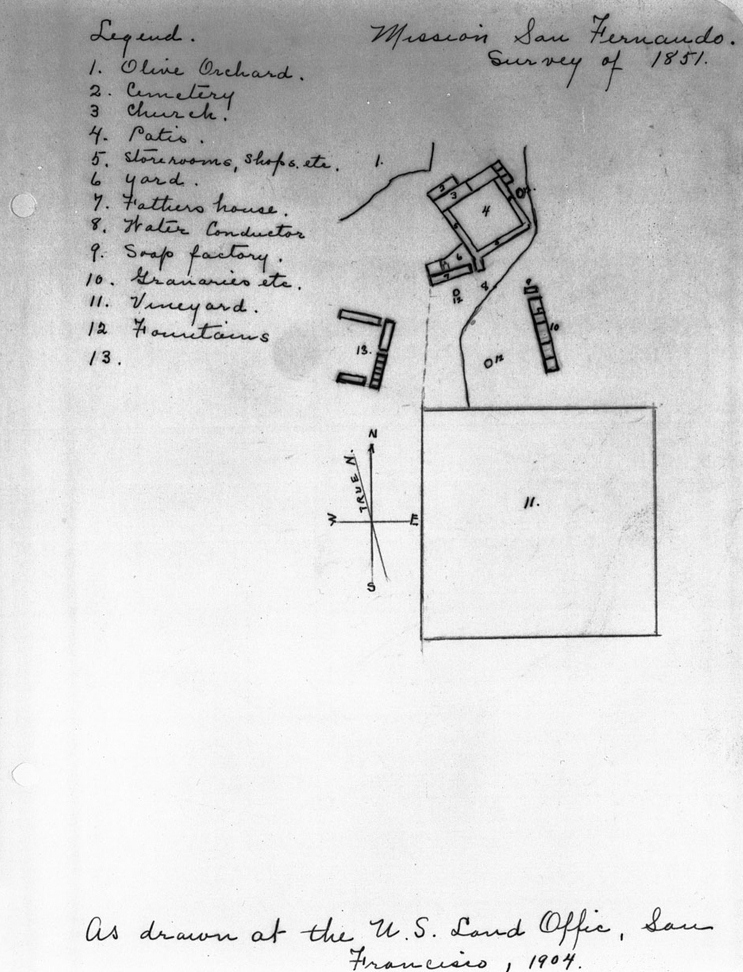

| (1904)* - Surveyor’s map of Mission San Fernando Rey de España, drawn at the U.S. Land Office in San Francisco in 1904 from an 1851 survey. The map identifies key mission features, including the olive orchard, cemetery, church, patios, storerooms, workshops, yards, water conductor, soap factory, granaries, vineyard, and fountains. A compass rose indicating true north is visible. |

|

|

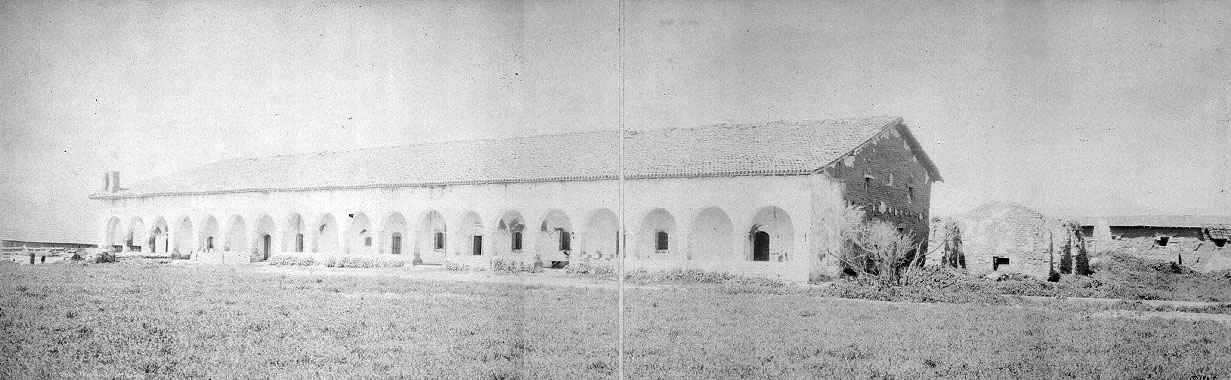

| (ca. 1907)* – Panoramic view showing the Convento Building at Mission San Fernando. The open landscape emphasizes the mission’s setting within a broad agricultural valley. Library of Congress. |

|

|

| (1910)* - View of a small canal and waterpipe supplying Mission San Fernando. A pipe feeds water into a concrete-lined canal flanked by bedrock, illustrating the mission-era irrigation infrastructure still in use in the early 20th century. |

Historical Notes Several natural springs supplied water to Mission San Fernando, supporting an extensive irrigation system that served the mission buildings, orchards, vineyards, workshops, and surrounding lands. This water network was essential to the mission’s agricultural economy and continued to influence land use well into the 20th century. |

|

|

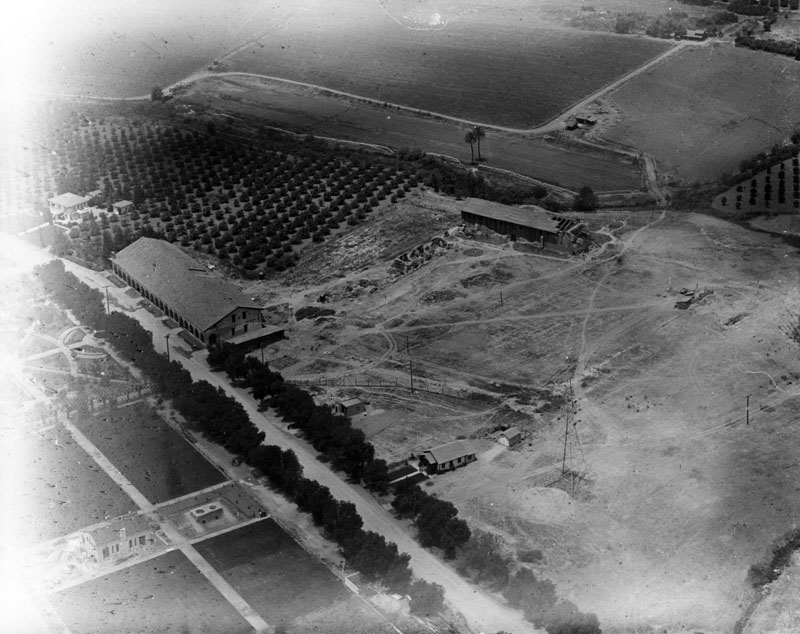

| (Early 1900s)*- Aerial view of Mission San Fernando showing the original chapel (upper right), the Convento Building (middle left), and surrounding lands. Across the road lies Brand Park, while plowed fields, likely former orchards, extend between the convento and chapel. The road that would become El Camino Real runs parallel to the mission complex. |

|

|

| (Early 1900s)* - View of Brand Park, located across the street from Mission San Fernando Rey de España. Visible features include the mission soap works, the original mission fountain relocated from its first site, and a large reservoir that once supplied water to the mission. Trees and landscaped grounds reflect the site’s transition from mission utility to public parkland. |

|

|

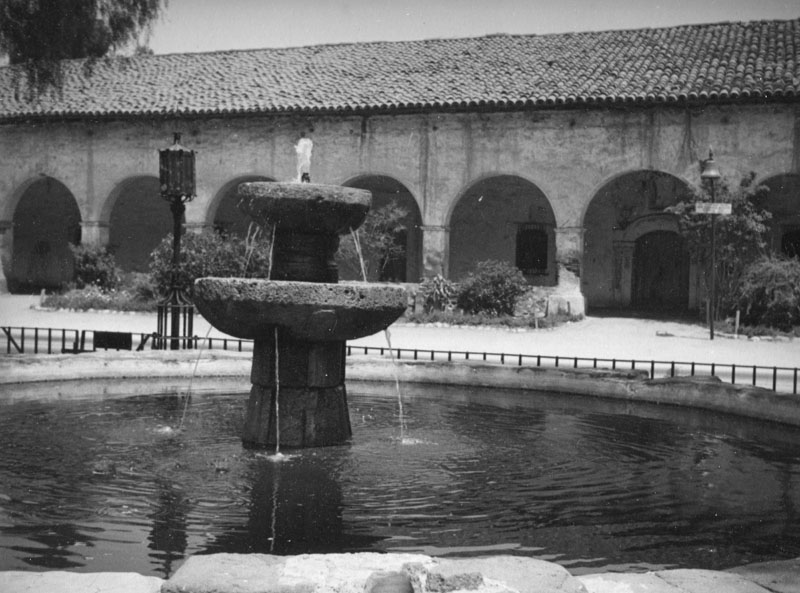

| (Early 1900s)* - View of the inner courtyard at Mission San Fernando Rey de España. A large circular fountain with a two-tiered centerpiece stands in the foreground, while adobe walls, archways, and tiled roofs surround the courtyard. Mature trees provide shade within the enclosed space. |

* * * * * |

From Historic Ruin to Public Landmark (1920s) |

By the 1920s, Mission San Fernando had begun its transition from a neglected historic ruin into a recognized public landmark. While restoration was still limited, increased visitation, civic interest, and symbolic improvements reflected a growing awareness of the mission’s historical and cultural importance. Photographs from this decade show the site as both fragile and newly valued, balancing preservation with public access. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of an unidentified woman seated on the ledge of the original mission fountain, which had been relocated approximately 30 feet from its original position. A sign reading “Keep Off Fountain” is visible. Nearby features include the mission soap works and a large reservoir that once supplied water to the mission. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of the Convento colonnade at Mission San Fernando Rey de España. The photograph shows the length of the corridor, arches, wooden beams, and decorative shadows on the floor. An El Camino Real bell marker is visible through the second archway. El Camino Real bell markers began appearing in the early 1900s. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of the Convento colonnade showing arches, beams, and multiple arched doors and windows opening into former living quarters. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of the Convento Building, also known as the Long Building, with an automobile parked along the road that would become El Camino Real. The presence of a car reflects the mission’s increasing accessibility and integration into modern transportation routes. |

|

|

| (1922)* - Fourth of July celebration at Mission San Fernando Rey de España. Los Angeles Times photo. Public gatherings such as this illustrate the mission’s growing role as a civic and cultural landmark. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - Aerial view showing the original chapel structure and the Convento Building, along with surrounding lands. Brand Park and its fountain are visible across the road, while fields behind the mission suggest continued agricultural use. El Camino Real runs parallel to the site, lined with trees. |

San Fernando Mission in the 20th Century In 1923, Mission San Fernando returned to active religious use when the property was transferred to the Oblate fathers. Restoration efforts proceeded gradually, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the mission’s history. Although the site had endured decades of neglect and adaptive use, the 1920s signaled a shift toward preservation, public engagement, and renewed spiritual function. Artifacts such as the original fountain, soap works, and water reservoir were preserved nearby, reinforcing the mission’s emerging identity as both a historic site and a living institution. |

* * * * * |

Restoration Era and the Mission Returns as a Working Church 1920s–early 1930s |

Following decades of neglect and adaptive use, Mission San Fernando entered a new phase in the early 20th century. In 1923, the mission returned to active religious life under the care of the Oblate fathers. Restoration proceeded gradually, combining structural repair with continued daily use of the mission. Photographs from this period document hands-on preservation, renewed community involvement, and the mission’s transformation into a functioning church and historic landmark. |

| Historical Notes

By the early 1920s, Mission San Fernando was no longer abandoned but had not yet undergone full restoration. Under the care of the Oblate fathers beginning in 1923, the mission returned to regular religious use while repairs were carried out gradually and as resources allowed. Photographs from this period show a working mission—still worn in places—serving parish life and the surrounding community. Structural deterioration, temporary repairs, and reused historic elements reflect a practical approach to preservation during the early restoration years. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920)^* - Exterior view of the entrance of the San Fernando Mission, showing the mission in active use prior to full restoration. |

|

|

| (1924)* - Photograph of the water intake irrigation system at Mission San Fernando, December 1924. Picture file card reads: "About 2 miles east of the mission. Right-hand side of wall constructed on picture". The intake is square-shaped and shows signs of deterioration, reflecting continued reliance on aging infrastructure during the early restoration period. |

|

|

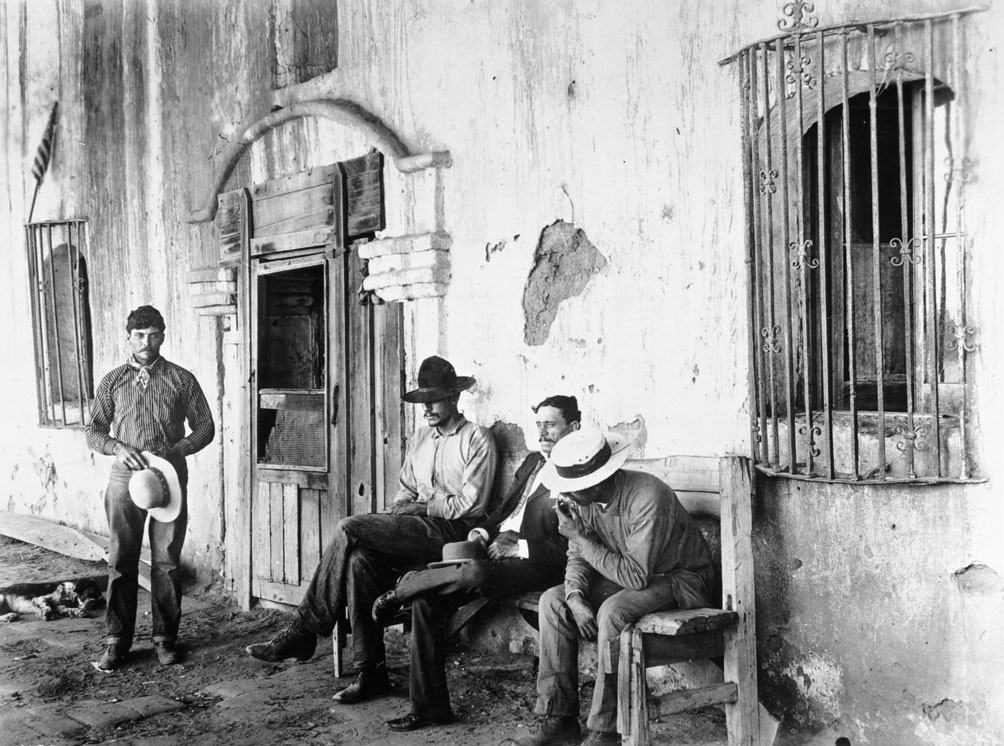

| (1924)* - Photograph of four Californian men near the entrance of Mission San Fernando, California, Cinco di Mayo, 1924. Three sit on a wooden bench, the fourth stands nearby, his hat in his hands. Stucco has fallen off of parts of the wall of the mission behind them. Decorative bars cover the two visible windows. A dog sleeps on the ground behind the standing man. The scene reflects the mission’s role as an active community gathering place during the early years of its return to church use. |

|

|

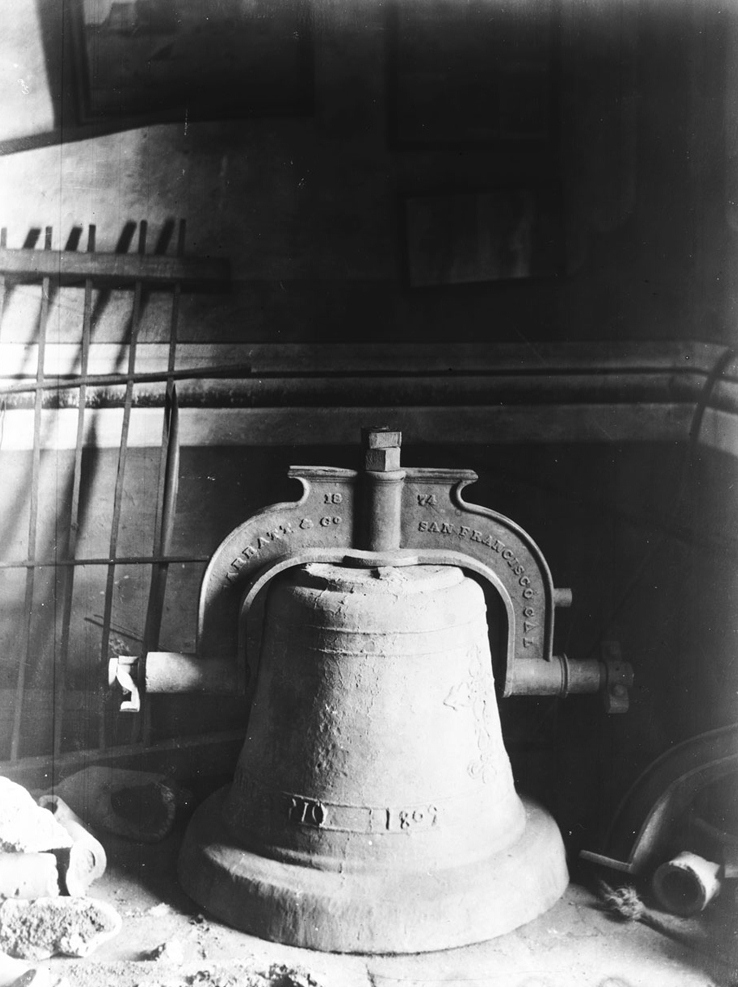

| (1926)* - Photograph of an old bell from Mission San Fernando. The large metal bell rests on the ground at center. It has a rough surface, and towards the bottom, the words "[¿]mo 1809" are embossed. The arch-shaped bracket that would be used to suspend the bell appears much newer than the bell itself. It is attached to the top of the bell and bears the words "[¿]arratt & Co. 1874 San Francisco Cal". There is a metal grate leaning on the wall behind the bell at left, and there is adobe debris on the ground at left. Several rectangular pictures are hung on the wall at center. The contrast between the older bell and its later mounting hardware reflects the adaptive reuse of historic elements during the restoration process. |

* * * * * |

Brand Park, Memory Garden, and the Mission Grounds (1920s) |

As Mission San Fernando reentered public life in the 1920s, the surrounding grounds took on new civic and commemorative roles. Brand Park, or Memory Garden, emerged as a landscaped counterpart to the mission, blending preservation, interpretation, and public use. |

|

|

| (ca. 1926)* - View of Brand Park across the street from the San Fernando Mission. An adobe archway frames the entrance to landscaped grounds with hedges, planters, and a central fountain. |

Historical Notes Brand Park, also known as Memory Garden, was given to the City of Los Angeles on November 4, 1920. The park occupies land that was once part of the original Mission San Fernando Rey de España land grant and was developed as a civic landscape complementing the historic mission across the street. Its design incorporated mission-era elements, including the original fountain and reservoir features, and reflected early 20th-century efforts to preserve and interpret California’s Spanish colonial heritage. In 1935, Brand Park was designated California Historic-Cultural Monument No. 150. |

|

|

| (ca. 1926)* - View looking northwest through the pergola of Memory Garden toward the San Fernando Mission. Adobe posts support a vine-covered wooden trellis, with benches lining the walkway. The mission’s arcades and adobe structures are visible in the background, visually linking the park’s landscaped grounds with the historic mission complex. |

| Historical Notes

Brand Park was designed as a civic landscape intended to preserve, interpret, and complement the historic mission across the street while providing public access. |

|

|

| (ca. 1937)* - Close view of the plaque at the Brand Park fountain, noting that the fountain was replicated from one in Córdoba, Spain, originally built between 1812 and 1814. The plaque also records that the fountain was relocated approximately 300 feet in 1922, following the donation of the property by Leslie Brand to the city. |

* * * * * |

Restoration Work and the Mission Landscape (Late 1920s–1930s) |

As restoration efforts at the San Fernando Mission gained momentum in the late 1920s, work on the historic buildings took place within a broader landscape that was still largely agricultural and only beginning to suburbanize. Adobe repair, traditional construction methods, and stabilization of long-neglected structures occurred alongside active orchards, early road development, and nearby historic sites tied to the mission’s rancho past. Photographs from this period place the physical restoration of the mission within its wider geographic and historical setting. |

|

|

| (1927)* - Photograph of men renovating Mission San Fernando Rey de España, showing adobe brick makers at work in the foreground. Rows of freshly formed adobe bricks dry in the open air as workers move materials by hand and wheelbarrow. |

| Historical Notes

Scaffolding and damaged walls visible in these images document hands-on restoration that relied on traditional adobe construction techniques rather than modern materials. |

|

|

| (1935)* - Aerial view looking north showing Sepulveda Boulevard curving into Brand Boulevard. Near the curve is the Andrés Pico Adobe, with the San Fernando Mission visible in the upper right. Orange and lemon groves fill much of the surrounding landscape, illustrating the largely agricultural character of the area during the mission’s restoration years. |

Historical Notes The Andrés Pico Adobe, built in 1834, is one of the oldest surviving residences in the San Fernando Valley. Constructed by Indigenous people associated with Mission San Fernando, the adobe originally stood within the mission’s orchards and vineyards. It later became the home of Andrés Pico, brother of California governor Pío Pico, and reflects the transition from mission control to rancho-era land use. By the 1930s, the surrounding landscape included citrus groves and packing facilities associated with the San Fernando Heights Lemon and Orange Association, illustrating the continued agricultural use of former mission lands during the period of mission restoration. Buildings tied to the citrus industry were located south of the adobe, situating the structure within a broader working landscape that linked mission history, rancho life, and early 20th-century agriculture. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)* - Bird’s-eye view over orchards on Mission San Fernando land, looking southeast from the Santa Susana Mountains toward the Cahuenga Pass. Dense rows of citrus trees stretch across the valley floor, while scattered residential development marks the early stages of suburban growth on former mission lands. |

Historical Notes This view was taken from a hillside near the location of today’s Odyssey Restaurant in Mission Hills. The San Fernando Mission appears at center-left, with homes along Memory Park Avenue—built in the mid-1920s—visible near the center of the image. Citrus packing buildings associated with the San Fernando Heights Lemon Association stand to the right, while Rinaldi Street cuts diagonally across the lower portion of the scene. |

* * * * * |

Mission Life, Architecture, and Public Presence (1930s–1940s) |

By the mid-1930s, restoration work at Mission San Fernando had progressed to the point where the site once again functioned as an active religious, social, and historic place. Courtyards, arcades, and interior spaces were stabilized and put to regular use, while visitors increasingly experienced the mission as both a living parish and a public landmark. Images from this period document how restored architecture, daily life, and growing public interest came together during the mission’s reestablished role in the San Fernando Valley. By this time, the mission had become a regular stop for visitors while continuing to serve its parish community. |

|

|

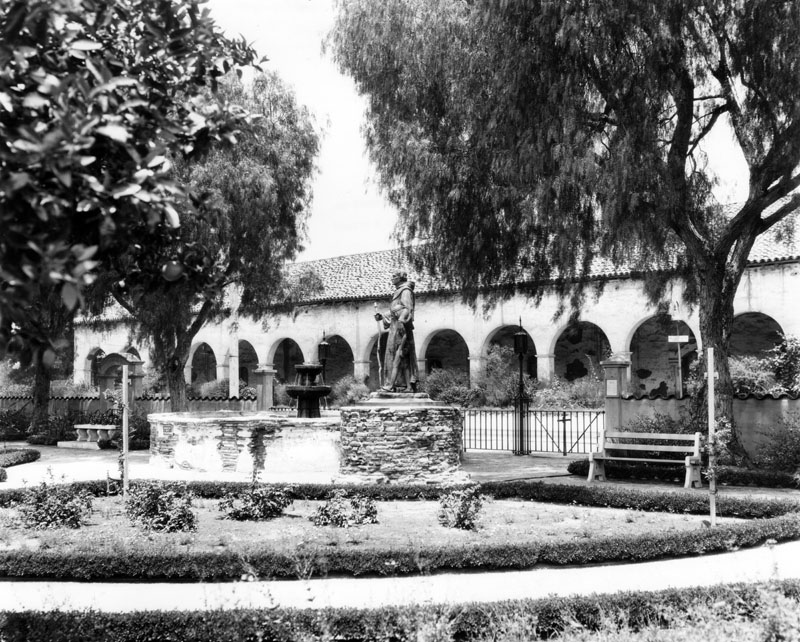

| (ca. 1936)* - View of the courtyard of Mission San Fernando Rey de España. A fountain and a statue of Father Junípero Serra are visible following stabilization of the mission grounds. |

| Historical Notes

By the mid-1930s, the mission courtyard functioned both as an active religious space and as a focal point for visitors, reflecting the site’s renewed public presence. |

|

|

| (ca. 1937)* - View looking north past the Brand Park fountain toward the south façade of the mission arcade and Convento Building. An El Camino Real bell appears at right, while period lighting fixtures and landscaped surroundings illustrate the mission’s growing public presence within a civic setting. |

|

|

| (ca. 1936)* - View of the Convento colonnade at Mission San Fernando Rey de España. The restored adobe arches and covered walkway highlight architectural continuity and the renewed circulation spaces connecting the mission’s buildings. |

|

|

| (1938)* - Interior view of a kitchen located in the Convento Building, also known as the Long Building. An oven, cooking nook, and staircase leading to an upper level illustrate the practical, day-to-day use of mission spaces during this period. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)* - Interior view of an attic or loft space within the Convento Building. Exposed rafters, adobe flooring, wall hangings, and open doorways reflect utilitarian interior spaces adapted for continued occupancy. |

|

|

| (1939)* - Painting of the interior plaza of the San Fernando Mission, with the central fountain depicted prominently. Such artistic views reflect contemporary interpretations of the mission as a historic and cultural landmark. |

|

|

| (1939)* - View of the Convento Building with automobiles parked along San Fernando Mission Boulevard. The presence of cars underscores the mission’s integration into everyday civic life by the late 1930s. |

|

|

| (1946)* - Members of a historical society caravan parked at the mission portico during a guided visit. The group’s presence documents organized heritage tours and growing public interest in the mission’s history. Photograph dated June 17, 1946. |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)^* – View of a car stopped in front of the Convento Building, or Long Building, at the San Fernando Mission. The scene reflects the mission’s continued use and accessibility in the postwar years. |

These images mark the point at which Mission San Fernando had fully reentered the civic and cultural life of the San Fernando Valley.

By the postwar years, the mission’s identity had shifted from a local landmark to a formally protected historic site.

* * * * * |

Later Views, Official Recognition, and Enduring Legacy (1950s–Present) |

This section highlights the mission’s transition into a protected historic landmark and its continued role as an active religious and cultural site. |

|

|

| (1955)* - View of the Convento Building, also known as the Long Building, as it appeared in the mid-1950s. The stabilized adobe structure reflects decades of preservation work following earlier periods of neglect and partial restoration. |

Historical Notes By the mid-20th century, Mission San Fernando Rey de España had emerged as one of the best-preserved mission sites in California. In recognition of its historical and architectural significance, the Convento Building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. In 1999, the entire mission complex was listed on the National Register, formally acknowledging the site’s importance at both the state and national levels. Mission San Fernando Rey de España has also been designated California Historic Landmark No. 157, recognizing its foundational role in the history of the San Fernando Valley and early California. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* - Postcard view of Mission San Fernando Rey de España, reflecting early 20th-century public interest in the mission as a historic landmark despite its incomplete restoration. |

Historical Notes Although preservation efforts began as early as the late 19th century, full restoration of the mission church was not achieved until the mid-20th century. Significant financial support from the Hearst Foundation in the 1940s made comprehensive restoration possible. In 1971, a major earthquake severely damaged the church, requiring it to be completely rebuilt. Restoration was completed in 1974. The mission continues to serve as an active parish church and remains carefully maintained. In 2003, entertainer Bob Hope was interred in the Bob Hope Memorial Gardens adjacent to the mission, further connecting the site to Southern California’s modern cultural history. |

|

|

| (ca. 1903)* - View of the Convento Building following its early 1903 restoration, with the original chapel structure at right still in a state of ruin. The image highlights the selective and incremental nature of early preservation efforts. Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

* * * * * |

Context and Wrap-Up: Then & Now and the California Missions Map |

These final comparisons place Mission San Fernando Rey de España within both its historical setting and its modern landscape. Together, they show how the mission has endured as a physical landmark while the world around it has changed. |

Then and Now |

|

|

| (1873 vs 2023)* – Southeast-facing view from above the present-day intersection of Rinaldi Street and Sepulveda Boulevard, looking toward Mission San Fernando Rey de España. The Hollywood Hills rise in the distance, with Cahuenga Pass visible as a low point along the ridgeline. In the modern view, Sepulveda Boulevard appears at lower right. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1890s vs. 2025)* - Then-and-now comparison of Mission San Fernando Rey de España. The long arched Convento Building remains largely unchanged, while surrounding roads, infrastructure, and transportation reflect more than a century of transformation. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1890 vs. 2020* - San Fernando Mission, then and now, showing how the mission’s main buildings and fountain have remained largely the same while the surrounding grounds have changed. |

| Historical Notes

The fountain and arcade at Mission San Fernando Rey de España appear in both images. Although the fountain has been restored and the grounds landscaped, the basic layout and architecture seen in the 1890s view are still recognizable today. The modern image shows the mission as it appeared before changes made in 2020. That year, protests across California led to renewed attention on monuments connected to the mission era. A statue of Junípero Serra near the mission was removed by the City of Los Angeles as a public safety measure and placed into storage. The statue was removed by the City, not by protestors. |

|

|

| Map showing the 21 missions in California. Mission San Fernando Rey de España was the 17th mission built in the State. Courtesy of the San Fernando Valley Historical Society & Adobe Museum.* |

Historical Notes By the time the final California mission was founded in 1823, the region had evolved from a sparsely explored frontier into a connected agricultural landscape. The 21 missions that form California’s Historic Mission Trail are located on or near modern Highway 101, which closely follows the route of El Camino Real, the Royal Road. This route linked the missions administratively, economically, and culturally, shaping early settlement patterns that continue to influence California today. |

* * * * * |

Closing Summary StatementsTaken together, these images trace Mission San Fernando Rey de España from its earliest days through decline, adaptation, preservation, and renewal. They reveal a site shaped not only by architecture and faith, but by people, land use, transportation, and time.Today, the mission stands as both a historic landmark and a living institution—not a relic of the past, but a continuous record of the San Fernando Valley and California itself. |

* * * * * |

Please Support Our CauseWater and Power Associates, Inc. is a non-profit, public service organization dedicated to preserving historical records and photos. Your generosity allows us to continue to disseminate knowledge of the rich and diverse multicultural history of the greater Los Angeles area; to serve as a resource of historical information; and to assist in the preservation of the city's historic records.

|

More Historical Early Views

Newest Additions

Early LA Buildings and City Views

History of Water and Electricity in Los Angeles

* * * * * |

References and Credits

* LA Public Library Image Archive

^* Oviatt Library Digital Archives

*# California Missions Resource Center

^# San Fernando Valley Relics: The Palms of San Fernando

#^ Facebook: West San Fernando Valley Then and Now

## Library of Congress: Panoramic View of Convento Building ca. 1907

***Los Angeles Historic - Cultural Monuments Listing

*^*California Historical Landmarks Listing (Los Angeles)

^^^Missions of California: Mission San Fernando, Rey de Espa˜a

*#*KCET - Brief History of Palm Trees

^#^Huntington Digital Library Archive

** Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mission_San_Fernando_Postcard,_circa_1900.jpg

++ The California MIssions Trail

*^ Wikipedia: San Fernando Mission; Charles Fletcher Lummis; Padre Fermín Lasuén

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index