LA's Early Water Works System

|

|

| (1939)* - Interior of Zanja Madre uncovered during wrecking of first Department of Water and Power building - The old “Zanja Madre” or mother ditch, carrier of much of Los Angeles’ water supply during the middle of the last century, has again became the subject of historical discourse. This time because workmen, while excavating on Olvera Street, came across traces of a small redwood bridge which used to cross it. |

From LADWP's Historical Archive

March 1943 – The water works system of Los Angeles is unique in several respects. The fact that the original pueblo was granted perpetual rights to the waters of the entire water shed of the Los Angeles River above the pueblo has often been repeated, and it is hardly necessary to call it to attention here. But it is perhaps not so well known that throughout the century and a half since the formal founding of the pueblo in 1781, the control of the river was never once relinquished. Part of this flow was leased to the Canal and Reservoir Company for irrigation from 1868 to 1877, and a portion was leased to the Los Angeles City Water Works Company for domestic distribution from 1868 to 1898, but the Zanja Madre and its branches were always controlled by the municipality.

Another point worthy of note is that perpetual inadequacy of the water works system prior to construction of the aqueduct. Most large cities put on construction programs that periodically bring them to the point where the engineers can lean back and feel that things are fixed for a while. It is true that the water works engineers of Los Angeles were striving to that end, and almost annually predicted that their program for the following year would be adequate for a considerable time. But just as regularly the remarkable expansion of the city exceeded all expectations and the capacity of reservoirs and pumps and truck lines was exceeded almost before they could be built.

Story from February 1948

In 1781, when Governor Felipe de Neve founded the pueblo of Los Angeles, he had definite instructions from the Spanish government as to the order in which the steps of establishment were to be made. After laying out the Plaza and allotting house sites, the first civic development was to bring water from the river to the little plaza, down to the huertas, or orchard tracts, that were given to each family, and on to the south, about where First Street is today. So a community ditch was built, each family contributing its share of labor, and it was called the “Zanja Madre,” or “Mother Ditch.”

The old mother ditch from which Los Angeles pueblo and city drew all its water, from the earliest days until well into the 1860’s, had its head at the old toma, a brush and dirt wing dam on the west side of the river, a short distance above the present North Broadway Bridge.

From that point, the water ran in an open ditch along the base of the bluff below old Buena Vista Street, now North Broadway, for about a mile and a half, and paralleled the street along the huertas de los Ybarra – the orchards of the Ybarra family, where now are cluttered the freight yards and tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad – and furnished irrigation to those once-lush fields. At College and San Fernando Streets, the zanja made an 18-foot drop in a three-foot brick conduit, supplying water power to the old Eagle Mills, called “Molina de la Zanja” by the early Spanish Californians.

The Eagle Mills, on the site of the present Capitol Milling Company, were built in the early ‘50’s, and have made history by having been the first instance of the development of industrial power, by water or otherwise, in the city of Los Angeles.

From this point the zanja veered to the southeast, crossing Main Street at Ord Street. Running through the block, it crossed Olvera Street diagonally between Macy and Marchessault. The runway across Olvera Street is now marked by diagonally-laid brick, with a tablet to designate it.

Here again the mother ditch contributed to power development when it turned a water wheel to run machinery in Perry’s Cabinet Shop, the same W. H. Perry who later became president of the Los Angeles Water Company. This shop was on the site of the two-story brick building of the water company which later became the first headquarters of the city-owned water works system at Marchessault and Alameda Streets.

From this corner, the Zanja Madre ran south between Alameda and Los Angeles Streets and then on Wilmington Street, now San Pedro, to First Street where it continued down San Pedro Street to Seventh Street. In later years the zanja was continued south from this point to the city limits as Zanja No. 4.

Along in the 1850’s, the development of orchards and vineyards south of Seventh Street, lying between Los Angeles and Figueroa Streets – then called Calle de las Chapules, or Grasshopper Street – created a demand for irrigation. This call for water was met by a branch of the Zanja Madre, later referred to as Zanja No. 8.

It was taken off at a point just south of Fourth Street and ran across to Fifth and Olive Streets, where it entered the present Pershing Square, then called “City Plaza” or “Central Park.” It ran through the square, along Olive Street, across Sixth and on south to the old Morris Vineyard at 16th and Main, irrigating as it flowed between Los Angeles and Figueroa Streets, the orchards of O. W. Childs.

This ditch, due to its very slight drop, was abandoned about 1870, when water was supplied from the old “Woolen Mill Ditch” to the west.

About 1854, the City Council installed a large water wheel at the toma to augment the water supply from the river to the zanja. This wheel was washed out twice during winter floods, and after the heavy flood of 1867 no attempt was made to rebuild it.

But the dam was strengthened, and another wheel was built opposite the present Solano Street to raise the water from the zanja to a brick reservoir built by Jean L. Sainsevain, just above old Buena Vista Street between the present Bishop Road and Solano Street. This reservoir was later abandoned when the present Buena Vista Reservoir was built.

It would be remiss of me not to mention the zanjeros who guarded and supervised the zanja. Among the best known of the many were Gaspar Valenzuela, who functioned as early as 1836; Don Cristobol Aguilar, and William Jenkins, one of the last zanjeros to manage the open zanjas in the city. Jenkins at one time had a force of several deputy zanjeros. He died but a few years ago, at the age of 91, and the writer has talked to him many times.

But, of all those who served, none is remembered with more kindly thoughts than Cristobol Aguilar, an alcalde in the Mexican regime and later a mayor of Los Angeles – the man who made sure the city’s rights were safeguarded in 1868, when the city’s water distribution system was leased to a privately-incorporated utility.

After his term as mayor, Aguilar accepted the then-important position of zanjero. Frank C. Naud, the son of Ed Naud – for whom Naud’s Junction on the early Southern Pacific line was named, and who built the first rat proof warehouse in the city – tells me, almost with tears in his eyes, of the memory of Don Cristobol’s kindly reasoning with the boys he caught swimming in the zanja.

Frank Naud, now almost 80, was born just above the old Sainsevain Reservoir, between Buena Vista Street and the Zanja Madre, in the large adobe residence of his grandfather, Jose Severiano Ybarra, called “La Casa de Sesenta Pasos.” Frank Naud’s earliest memories are of old Zanja Madre.**

|

|

| (1869)* - The Plaza and 'Old Plaza Church (Mission Nuestra Senora Reina de Los Angeles). The square main brick reservoir in the middle of the Plaza at the right was the terminus of the town's historic lifeline: The Zanja Madre. |

|

|

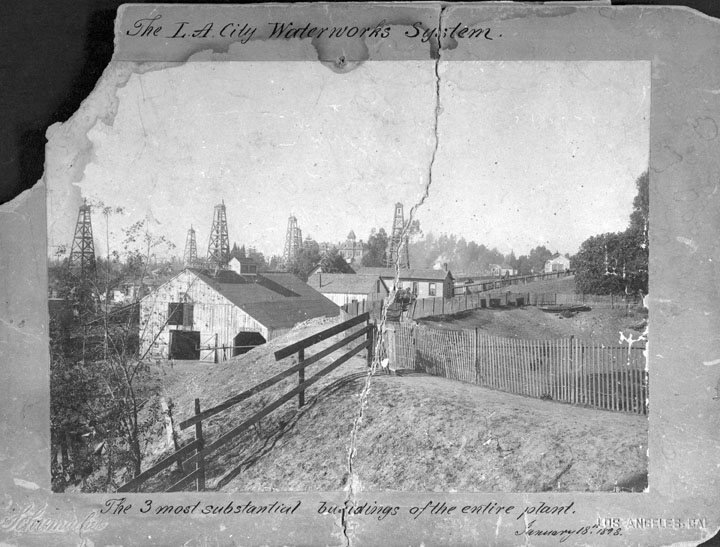

| (January 18, 1898)* - The LA City Waterworks System buildings. |

From LADWP's Historic Archive

As the much quoted Chinese proverb puts it. “A picture is worth 10,000 words.” The original print is labeled “the three most substantial buildings of the entire plant,” referring to the waterworks system of that period.

The large building in the left foreground was the stamping place of the horses and mules comprising the transportation facilities of the period. The small house immediately in back of it was the home of the works “smith,” who was available for emergency repairs to stock or equipment. To the left of these structures, but not shown in the picture, was the pipe yard where pipe and miscellaneous supplies were stored. Located near College and Figueroa (then known as Pearl) streets.

Close inspection of the right hand portion of the cut will show a boat high and dry inside the picket fence. Until 1894 a reservoir was in service there also. Fred Fisher, veteran chief of the pumping plants and reservoirs division, began his long service period in 1899 at the pumping plant used to lift water from his small reservoir to Beaudry and Angeleno reservoirs, the latter being in back of the old Sisters’ hospital. None of these storage basins is now used by the Department.

Picture taken January 18, 1898 shows important buildings of private water company just prior to purchase by City – March 1, 1935 the Bureau of Water Works and Supply, second largest municipally owned water system in the United States, recorded its 33rd birthday.

Municipal operation of the Los Angeles water system, however, dates back to the founding of the city in 1781. From that time until 1865 water was distributed under a community ownership arrangement. In that year the town council voted to lease the water system to private control and three years later again voted to leave operation of the city’s water supply to private interests by signing a 30-year lease with a concern known as the City Water Company.

As the years passed, the fallacy of that action was more and more painfully apparent to the citizens of the rapidly growing pueblo. High water rates and indifferent service were retarding the city’s growth. It was thus inevitable that at the end of the lease period citizens demanded that operations of the water system return to municipal ownership. As a result of public demands the city on March 1, 1902, purchased the existing equipment of the City Water Company for $2,000,000 and immediately put into effect a 63 per cent reduction in water rates.

All these years the Los Angeles River was the sole but adequate source of water supply. Under normal conditions it could meet the needs of a quarter million people but a series of dry years so reduced the water supply as to tax all available sources in order to serve the needs of the 160,000 city inhabitants. In addition, the population was rapidly increasing.

Choosing between a cessation of city growth or development of additional water supply, the citizenry in 1907 voted the unprecedented sum of $23,000,000 to be expended in constructing the epochal Owens River Aqueduct. Completed in 1913, the giant water carrier wound its serpentine length a distance of 230 miles over mountains and desert from the high Sierra to Los Angeles and assured its residents of a dependable supply of pure, sparkling mountain water.

Many interesting comparisons may be made between the Water Bureau of 1902 and the present organization; it was pointed out by H. A. Van Norman, Chief Engineer and General Manager. In 1902 the approximate population of 150,000 used 34,000,000 gallons of water daily. Last year (1934) the 1,250,000 people residing in the city needed 74 billion gallons for the year, which represents a daily consumption of 156,000,000 gallons.

The distribution mains have increased from 325 miles to more than 3,700 miles and pipe sizes have been increased proportionately. The largest diameter pipe in the present system measures 78-inches. Thirty-nine pumping plants now are necessary to maintain a dependable water supply. Gross receipts for the fiscal year in 1902 amounted to approximately $450,000. Today the annual revenue collected by the Bureau is nearly $10,000,000. The system which cost the city $2,000,000 in 1902 now has assets of over $140,000,000.

Interesting changes in the method of billing water users have taken place throughout the years of municipal ownership. Under an ordinance adopted in 1907 by the City Council, setting the water rates for the current year, the “ifs” were much in evidence. If your home contained more than 10 rooms an additional charge of five cents for each room over that number was made. And if you had a bath tub your monthly bill jumped 15 cents. Each cow cost only an additional 10 cents; a horse added 15 cents, but owners of a “horseless carriage” had to dig down for 20 cents extra each month. Charges for lawn sprinkling depended upon the lot frontage and depth.

Intricate rate schedules no longer are necessary in billing consumers since the water system has been placed on a 100 per cent metered basis. Metering of individual service connections also has greatly reduced the per capita consumption. In 1903 this rate was 240 gallons per day, indicating a great waste when compared with last year’s daily per capita of 116 gallons measured by approximately 245,000 meters now in service over the water system.**

|

|

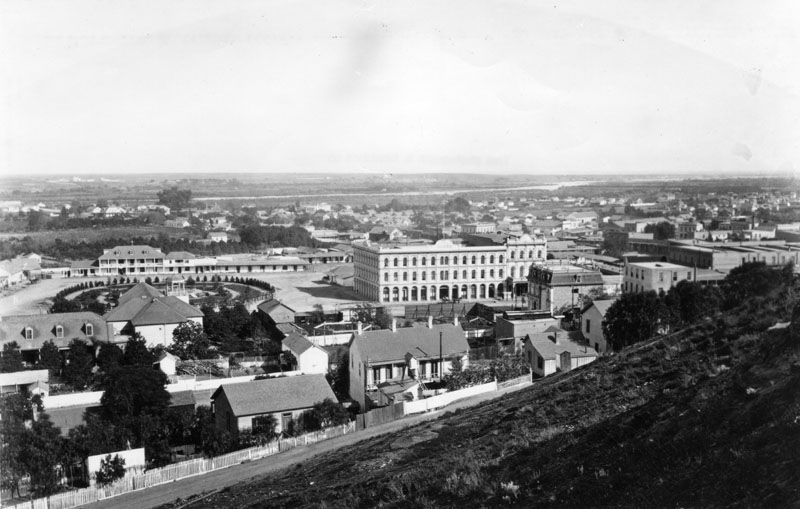

| (1876)* - Panoramic view of the Los Angeles Plaza in 1876. The Pico House is the prominent 3-story white building at the center of the photo. The Los Angeles River can be seen in the background. |

|

|

| (1890s)* - View looking northeast of The Los Angeles Plaza. The LA City Water Company, with its large sign on the face of its building, is at the northwest corner of Marchessault and North Alameda. The area to the east of the LA City Water Co. building and across Alameda is now occupied by the Union Terminal. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)** - View of the Plaza Fountain. Several men appear to be reading the daily newspaper. A horse drawn wagon can be seen in the upper left. Click HERE to see more Early Views of the L.A. Plaza. |

|

|

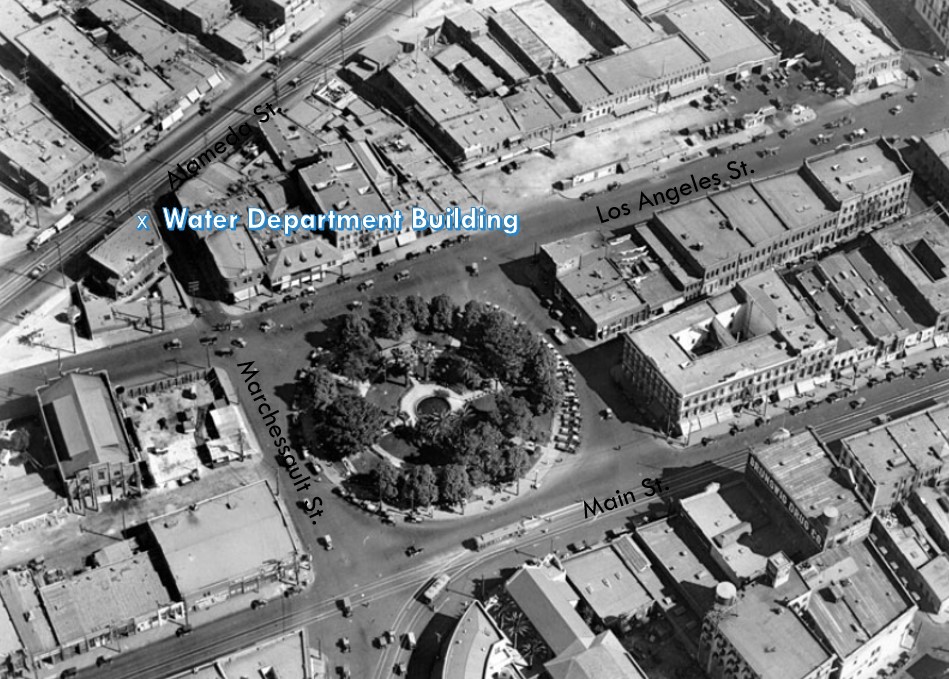

| (ca. 1924)*^ - Aerial view of the Los Angeles Plaza and surrounding buildings. The Water Department building can be seen in the upper left of the photo on the northwest corner of Alameda and Marchessault streets. |

Historical Notes The sole occupant of the entire city block (bounded by Los Angeles, Marchessault, and Alameda streets) was a sturdy, square, two-story brick structure. Built originally for a furniture factory, it was later remodeled to serve as a headquarters of the Los Angeles Water Department’s predecessor, the Los Angeles City Water Company. Click HERE to see more in Water Department's Original Office Building |

Click HERE to see more in Water in Early Los Angeles |

* * * * * |

History of Water and Electricity in Los Angeles

More Historical Early Views

Newest Additions

Early LA Buildings and City Views

* * * * * |

References and Credits

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

*^LA Public Library Image Archive

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Mulholland Service Award

- Major Efforts

- Board Officers and Directors

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index