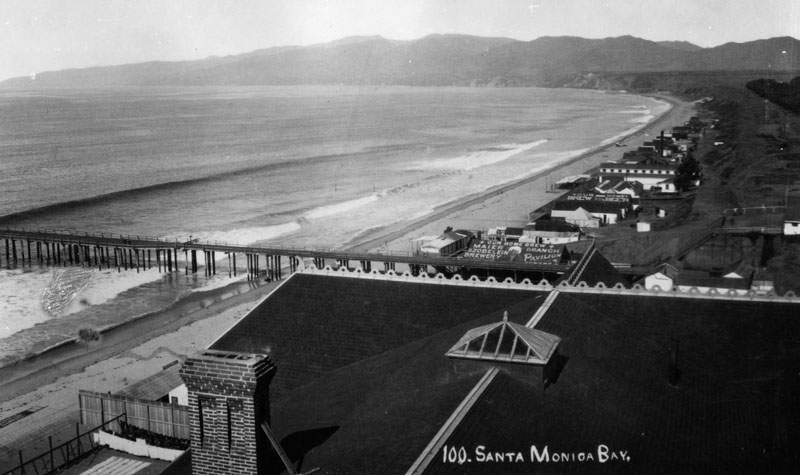

Early Views of Santa Monica

Historical Photos of Early Santa Monica |

|

|

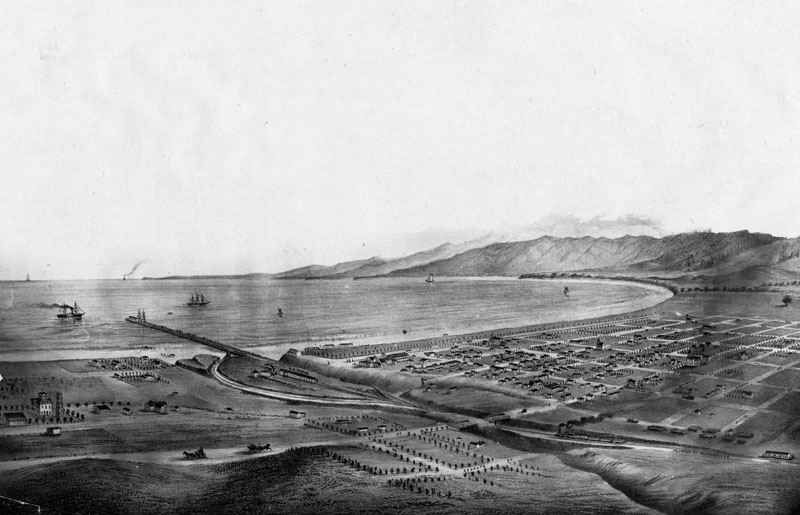

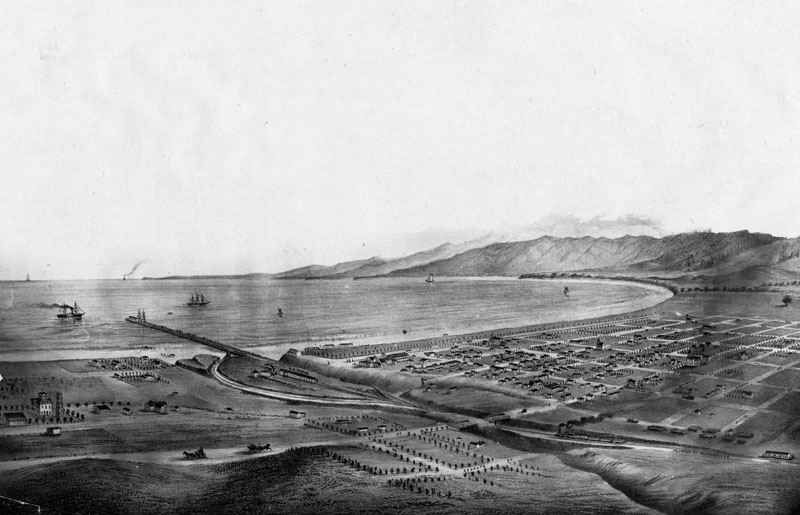

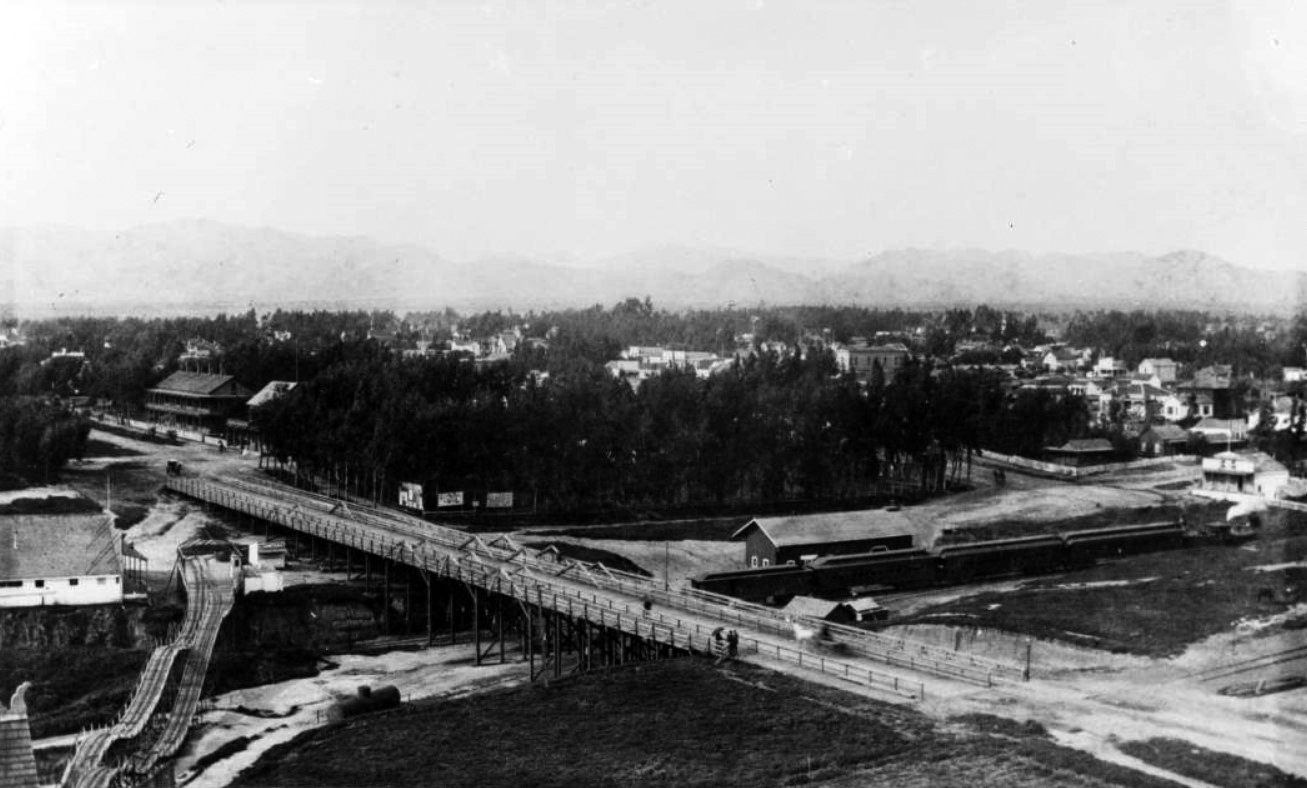

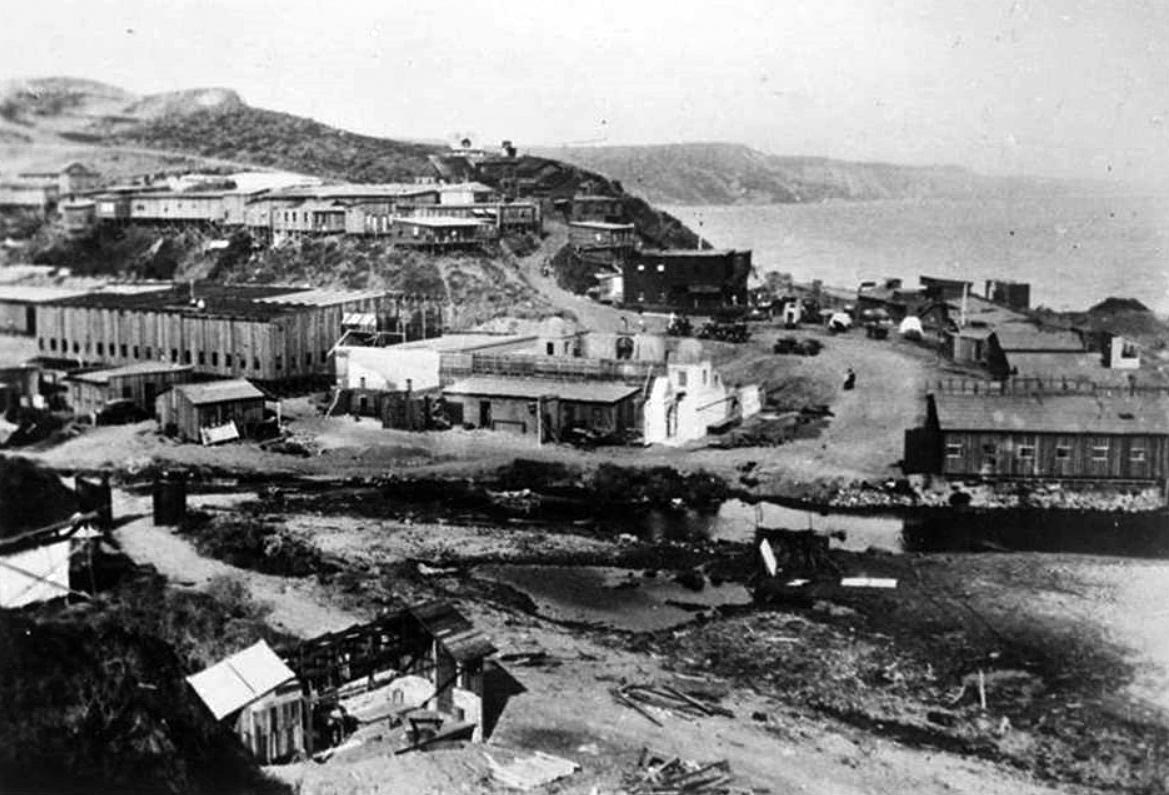

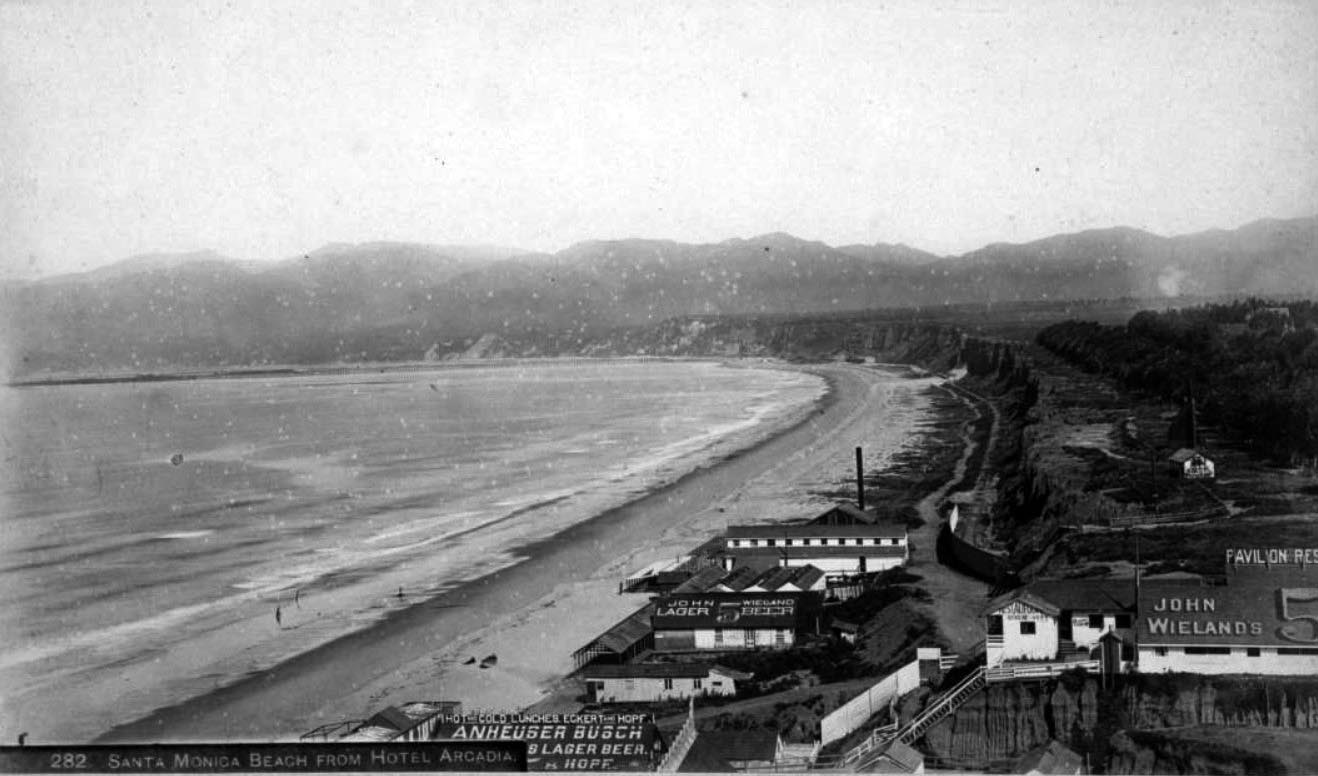

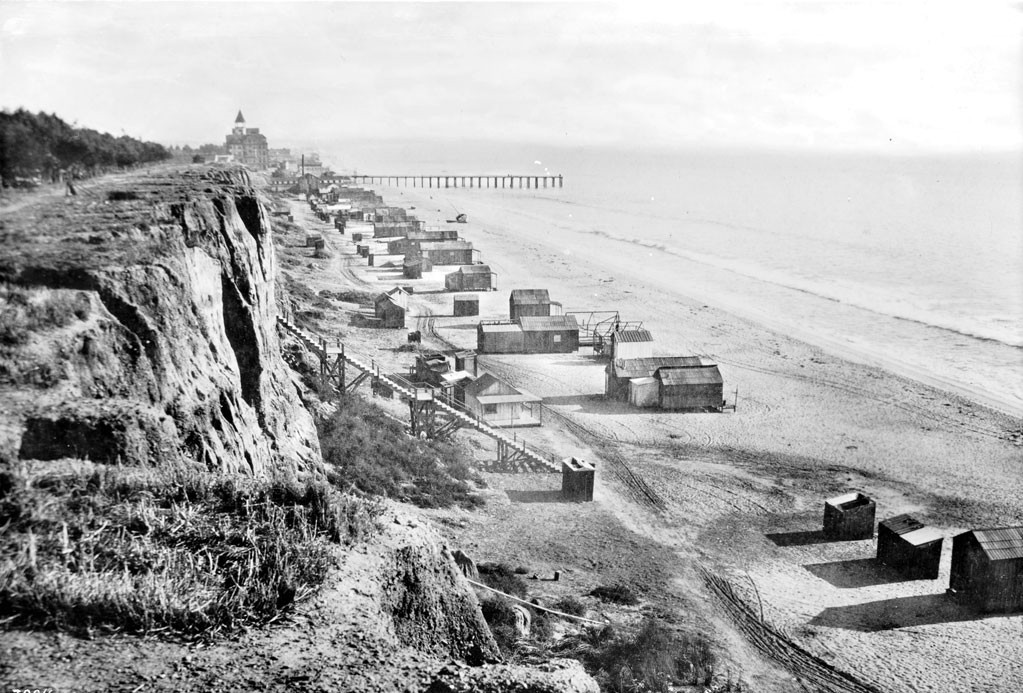

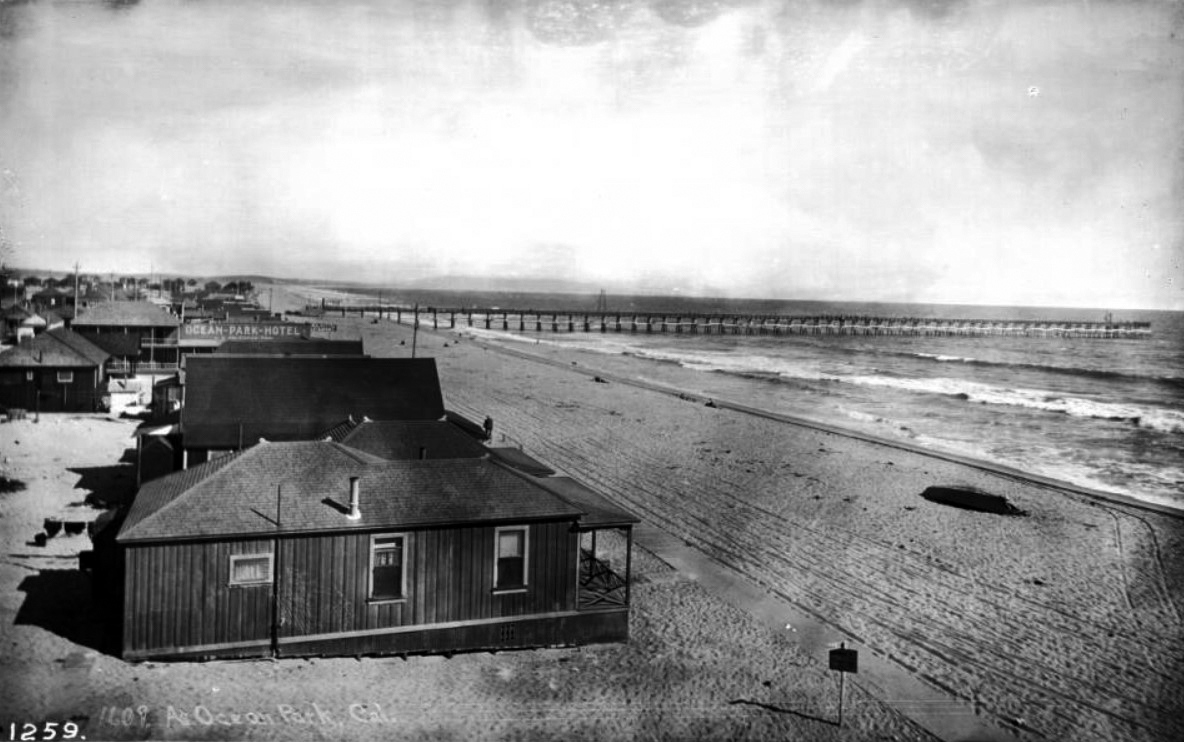

| (ca. 1875)* - View of Santa Monica and bay showing the road and wharf of the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad, about 1875. The wharf was completed in 1875 and sold in June 1877 to the Southern Pacific Railway Company, This print was photographed from an old lithograph. |

Historical Notes To make the town marketable, Jones built a 16-mile rail line between the Santa Monica Bay waterfront and downtown Los Angeles, naming it the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad. It was only the second railroad built in Los Angeles; the first was the Los Angeles and San Pedro, which opened in 1869. |

|

|

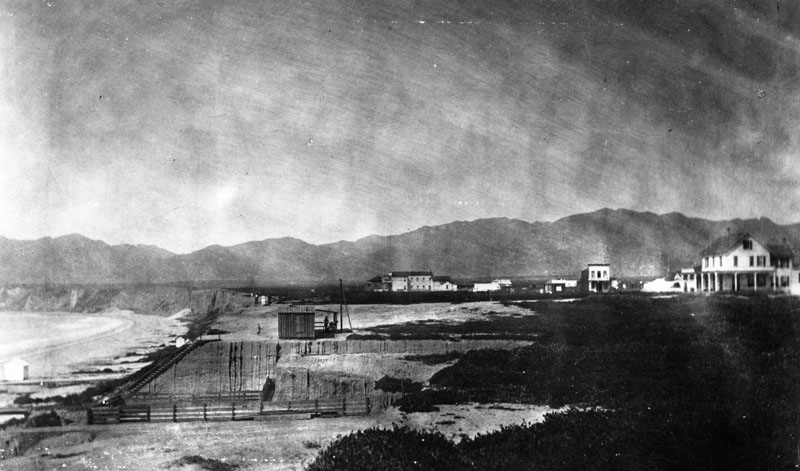

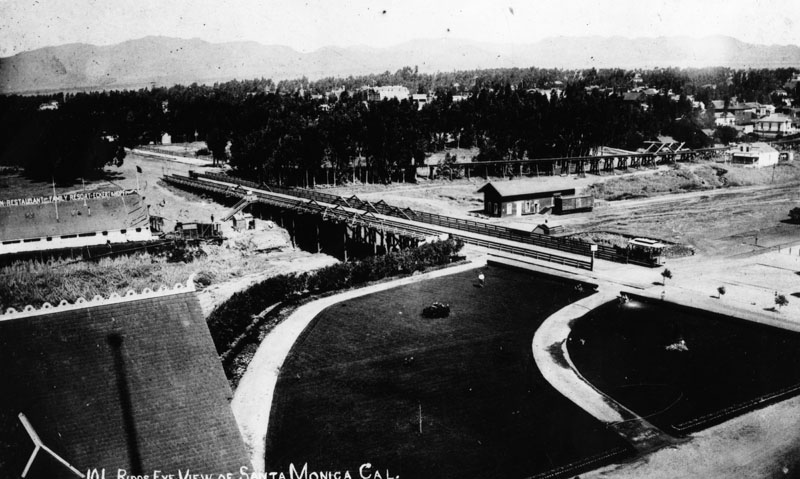

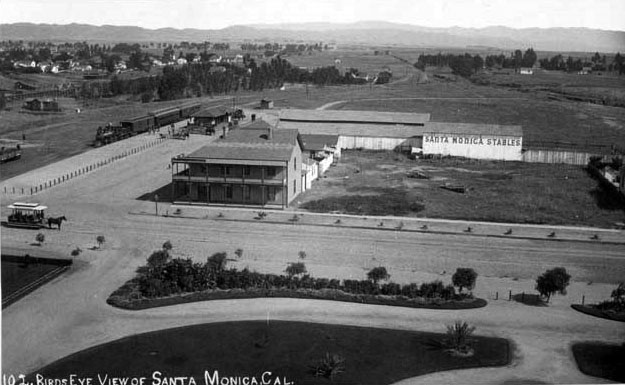

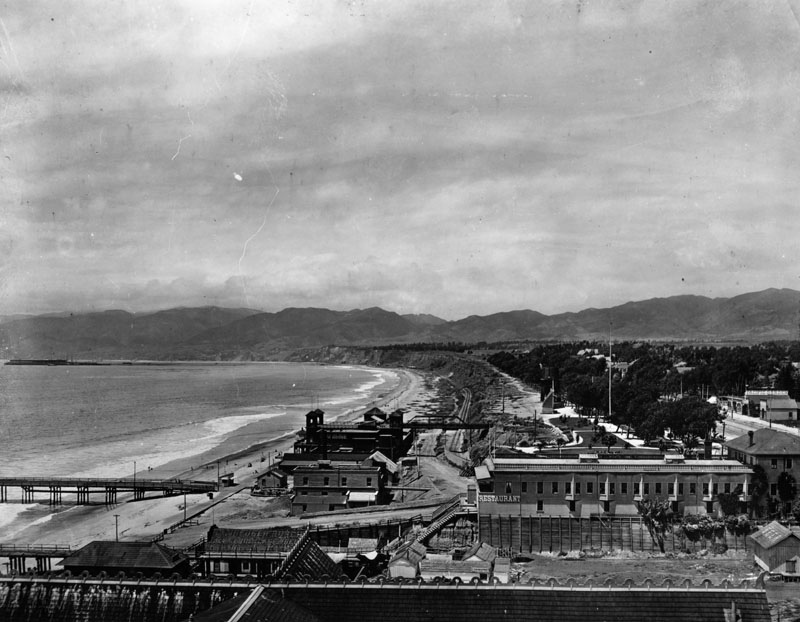

| (1877)* - View of Santa Monica looking north from the present Colorado Street, overlooking Ocean and 2nd Avenues. |

Historical Notes |

|

|

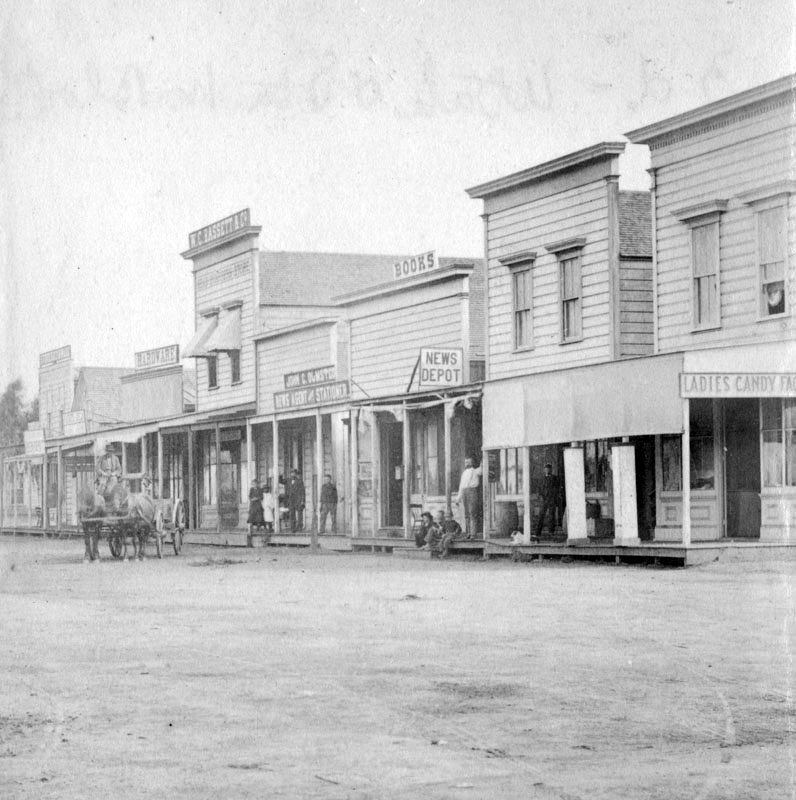

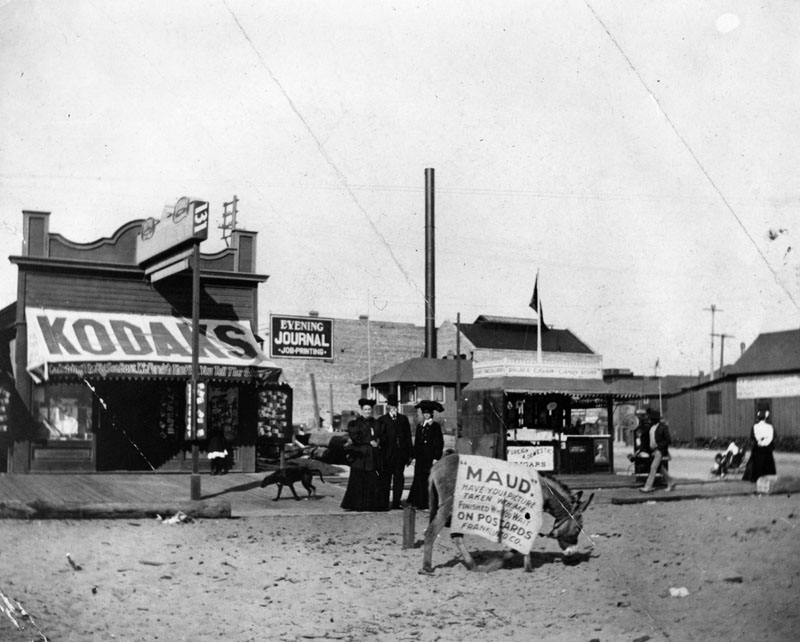

| (1875)* - Investors gathering to buy lots in Santa Monica which was promoted as the "City by the Sea." |

Historical Notes The land was auctioned on July 15, 1875 by the San Francisco Office of the Santa Monica Land Company. The advantages of Santa Monica were emphasized, particularly the superiority of its harbor over that of San Pedro. The lots sold for $500 and $750. Within a few weeks after the town lot sale a change had come over the barren plain. Houses and stores sprang up, a general store was opened and a newspaper started. |

* * * * * |

Third Street (Today, 3rd Street Promenade)

|

|

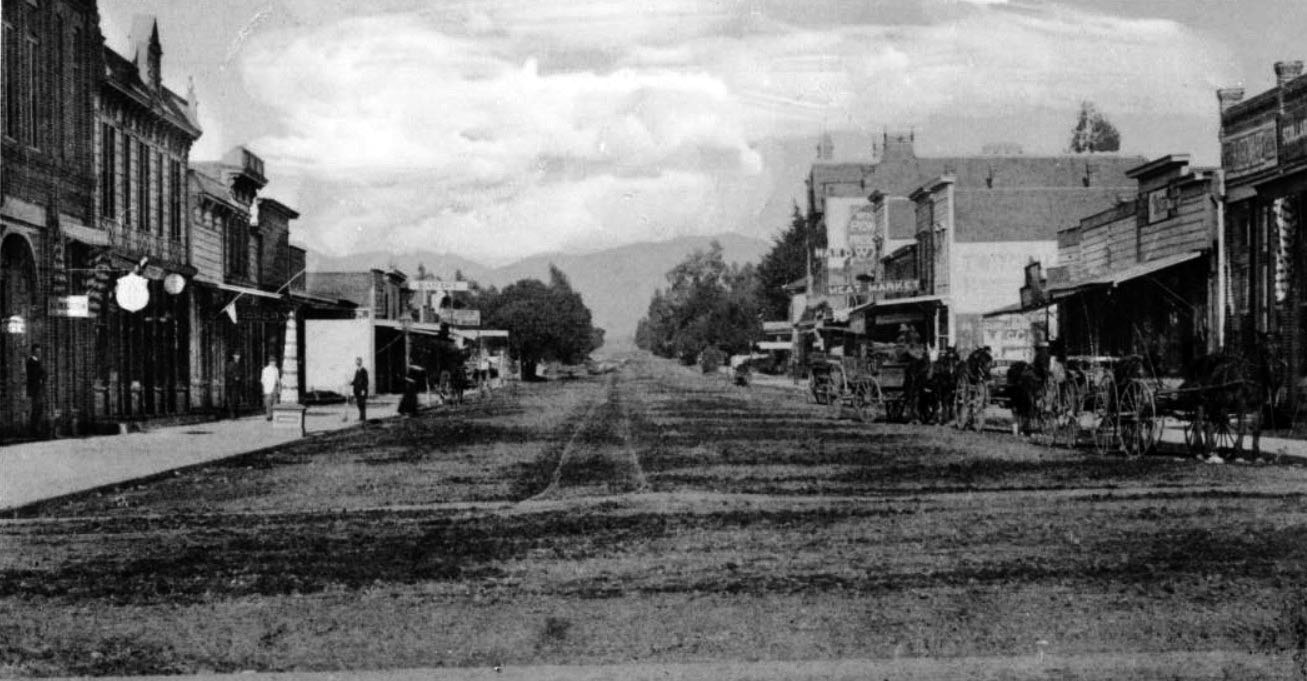

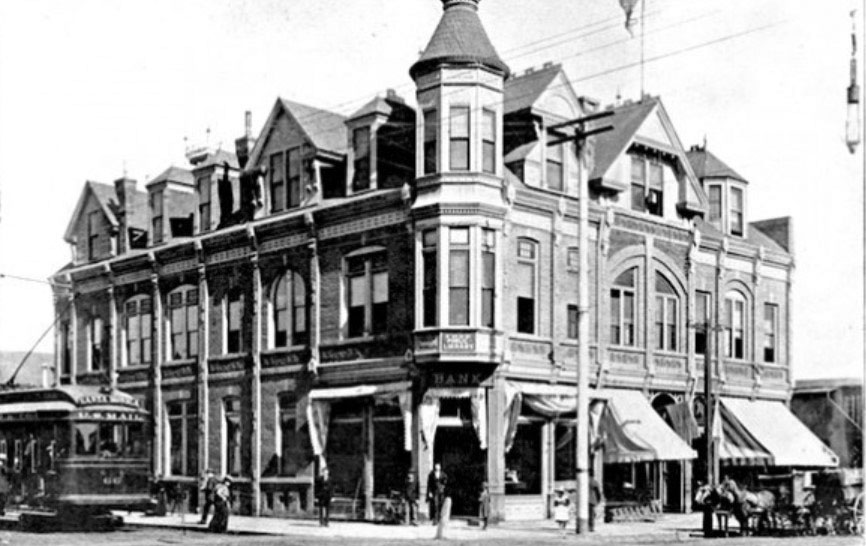

| (1880)* - A view of the business block on Third Street, between Utah (now Broadway) and Oregon (now Santa Monica Boulevard), shows what is today the site of the 3rd Street Promenade. This image was taken before Santa Monica became a city in 1886. |

Historical Notes The town continued to grow and, in November 1886, the electorate went to the polls and voted 97 to 71 to incorporate Santa Monica. |

|

|

| (1880)* - A view of the business block on Third Street, between Utah (now Broadway) and Oregon (now Santa Monica Boulevard), shows what is today the site of the 3rd Street Promenade. This image was taken before Santa Monica became a city in 1886. Photo enhanced and colorized by Richard Holoff |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1890)* - Four men and a child standing in the entrance to McKinnie's Pharmacy located on 3rd Street in Santa Monica, with a sign for "Mac's Favorite" on the sidewalk and the signs "Drug Store" and "Furnished Rooms" on the window of the brick building. Today, this site is located at Santa Monica’s 3rd Street Mall. Ernest Marquez Collection |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - A group of men and three young children pose for the camera in front of the Del Mar Ice Cream Parlor, located on the 1400 block of 3rd Street in Santa Monica. Signs painted on the side of a horse-drawn cart read "Wholesale and retail ice cream and confectionery, the Del Mar Ice Cream Parlors, Christopher's Ice Cream, Santa Monica." Today, this site is part of Santa Monica’s 3rd Street Mall. Ernest Marquez Collection |

|

|

| (ca. 1891)* – Panoramic view of Santa Monica's Third Street from Utah (now Broadway) to Nevada Boulevard (now Wilshire). The dirt street is lined with square buildings containing various shops and stores. Several horse-drawn wagons are lined up at right, and there are pedestrians at left. The Opera House and the Catholic Church are on the right side of the street, while the First Presbyterian Church is on the corner of Nevada. The First Presbyterian Church can also be seen at the corner of Nevada Boulevard. |

Historical Notes The original naming convention for east-west avenues in Santa Monica, established when the townsite was laid out in 1875, used names of Western U.S. states and territories. In later years, many of these street names were changed. For example: |

|

|

| (2024)* - Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica, looking northwest on Third Street at Broadway. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1891 vs 2024)* - Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica, looking northwest on Third Street at Utah (now Broadway). |

|

|

| (ca. 1896)^^ - Third Street looking north from Colorado Street, towards Broadway and Santa Monica Boulevard. View shows dirt street lined with clapboard stores and shops, one two-story brick castle-like building with crenelated turret (left center), W.T. Hull Furniture sign on roof of building at right, street trolley at distant center. |

Historical Notes Cllick HERE to see more early views of 3rd Street (1910), which would later become the 3rd Street Promenade. Click HERE to see more early views of the 3rd Street Promenade (1933+) |

* * * * * |

Los Angeles & Independence Railroad

.jpg) |

|

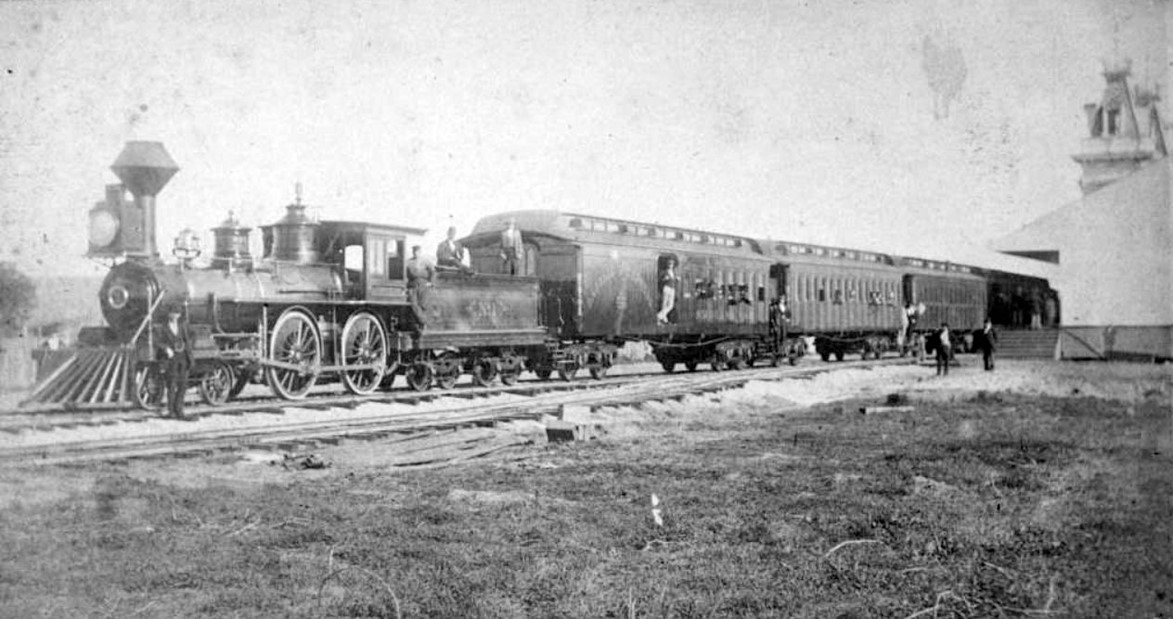

| (1876)* – A view of Los Angeles & Independence Railroad (LA&I) Locomotive No. 1, which operated between downtown Los Angeles and Santa Monica. Photo is from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

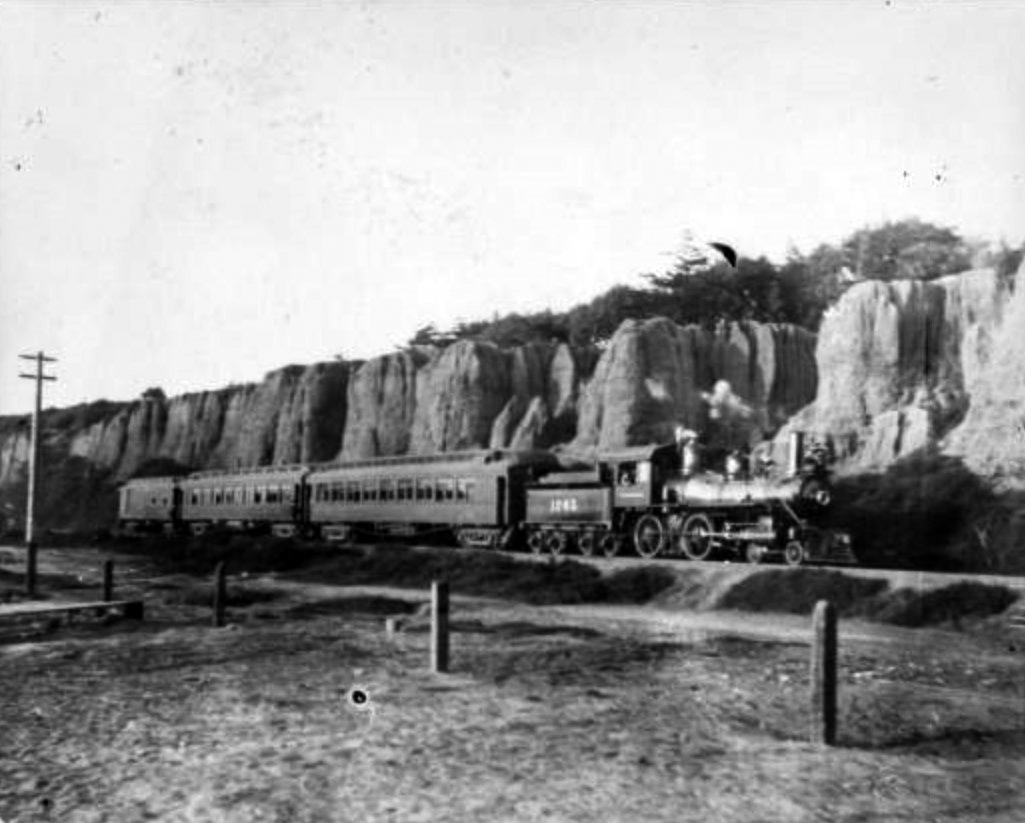

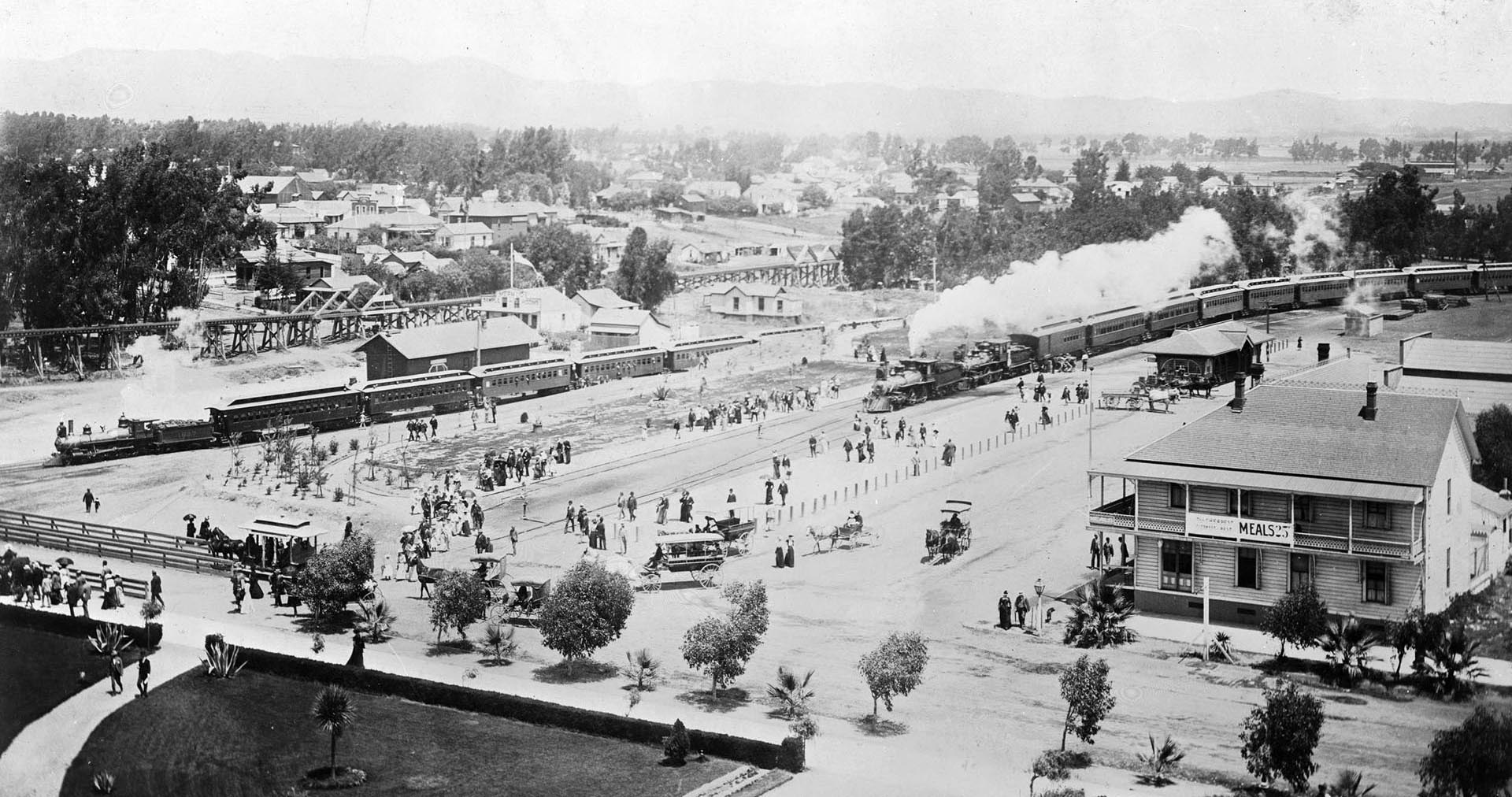

Historical Notes The Los Angeles and Independence Railroad (LA&I) was a significant early railroad in Southern California, chartered in March 1874 and beginning operations on October 17, 1875. It ran a 16.67-mile steam-powered line between Santa Monica's Long Wharf and downtown Los Angeles. Initially ambitious, the LA&I aimed to reach San Bernardino and Independence, to serve the Cerro Gordo Silver Mines. Key figures in its establishment included former governor John G. Downey and banker F.P.F Temple. The railroad faced fierce competition from the Southern Pacific, engaging in the "Battle of the Pass" to secure a route through Cajon Pass. Despite completing its line and formally opening on December 1, 1875, the LA&I struggled to compete with Southern Pacific's extensive network and pricing strategies. |

|

|

| (1876)* – View showing Locomotive No. 1 and passenger cars of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad on train tracks next to the railroad's terminal at Fifth Street and San Pedro Street in Los Angeles. The train is full of passengers and is about to leave for Santa Monica. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes The Los Angeles and Independence Railroad travelled from a wharf North of the current Santa Monica Pier in Santa Monica along a private right-of-way to 5th and San Pedro Street in downtown Los Angeles. The 16.67 miles of track between Los Angeles and Santa Monica were built by John P. Jones without government subsidies or land grants, all in a little over ten months - primarily using 67 Chinese laborers imported for the task. Right-of-way between Los Angeles and Santa Monica was given by local ranchers who were anxious to have access to a railroad. Click HERE to see more on the Los Angeles & Indempendent Railroad Depot in downtown Los Angeles. |

|

|

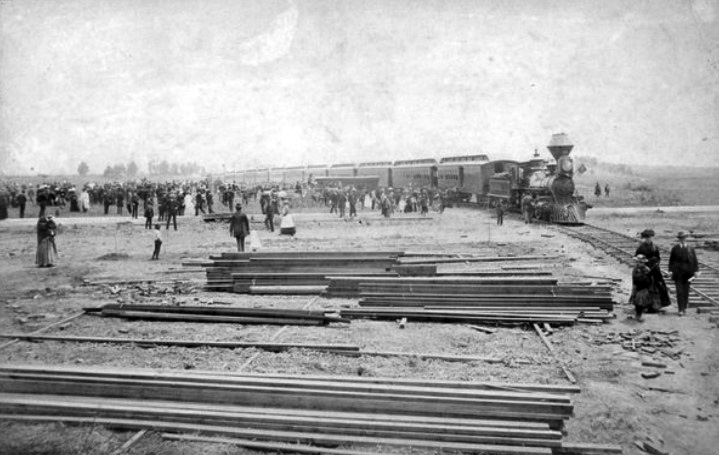

| (ca. 1878)* - Crowds of people surround a train in Santa Monica shortly after the Los Angeles & Independence RR was acquired by Southern Pacific. Piles of lumber are seen in the foreground. |

Historical Notes The line opened October 17, 1875, with two trains a day running between Santa Monica and Los Angeles; the fare was fixed at $1.00 per trip, freight at $1.00 per ton. |

|

|

| (ca. 1878)* - View of a Los Angeles & Independence line passenger train sitting in front of the Santa Monica railway station. Several men standing on and adjacent to the train are posing for the photographer. |

Historical Notes The Los Angeles and Independence Railroad helped make Santa Monica palatable to real estate speculators and prospective residents, but Jones, who was politically well-connected as a U.S. senator from Nevada, had grander plans for the railroad. Intending to connect the line with the town of Independence in the Owens Valley, and from there to a silver mine he owned in the Panamint Mountains, Jones optimistically included "Independence" in his railroad's name. Jones, however, encountered financial problems stemming from his mines drying out. He reluctantly sold the Los Angeles and Independence to Collis P. Huntington's Southern Pacific Railroad on July 1, 1877 for $195,000. Click HERE for more on the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad. |

* * * * * |

Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Wharf (aka Shoo Fly Wharf)

|

|

| (1877)* - View of the wharf built by the Los Angeles Independence Railroad Co. in Santa Monica (aka Shoo Fly Landing). |

Historical Notes As soon as work started on Los Angeles Independence Railroad line from Los Angeles to Santa Monica the construction of a new wharf was begun. This was located near the old "Shoo Fly" landing and near the present foot of Colorado Avenue, where a stub of the old wharf still remains. The first pile was driven April 22nd, 1875, and the first boat landed at the wharf in June. This wharf was 1700 feet in length and reached a depth of thirty feet at low tide. It was substantially built, with depot, and warehouses at its terminus and cost about $45,000. The wharf would be sold to Southern Pacific Railway Company in 1877. One short year later, Southern Pacific deemed the wharf unsafe for train usage and by 1888 it was torn down. |

|

|

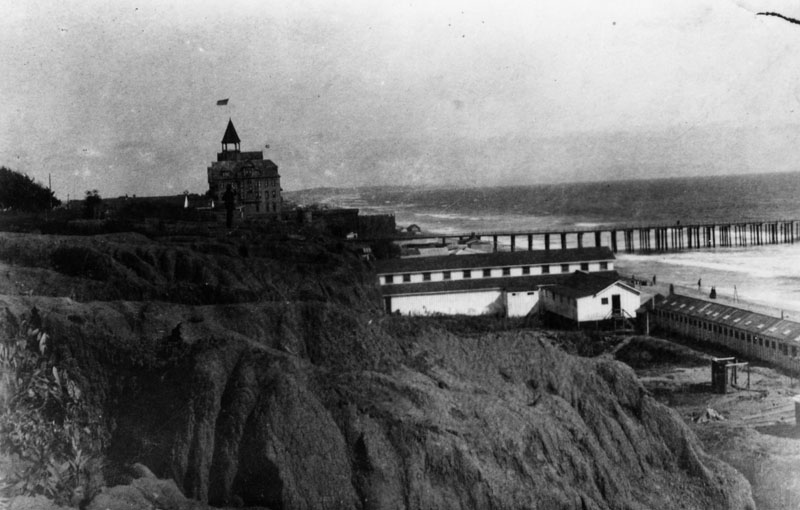

| (1877)* - Panoramic view of the shoreline as seen from the roof of a railroad train at end of the Los Angeles and Independence Wharf with the Santa Monica Hotel on the Palisades bluffs and the Santa Monica Bath House on the beach below. |

Historical Notes The wharf stood just south of the present location of the Santa Monica Pier at the foot of Colorado Avenue. Photo date devised based on the history of the Santa Monica Hotel, which was built in 1877 and the history of the photographer, Carleton E. Watkins, who made two visits to Southern California in 1877 and 1880. |

|

|

| (ca. 1875)* - View of Santa Monica and bay showing the road and wharf of the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad (aka Shoo Fly Wharf). The wharf was completed in 1875 and sold in June 1877 to the Southern Pacific Railway Company, This print was photographed from an old lithograph. |

Historical Notes The east-west street adjacent to the railroad tracks was initially named "Railroad Avenue" due to its proximity to the rail line. This street would later be renamed Colorado Avenue in 1902, reflecting the practice of naming streets after western states. |

Then and Now

|

|

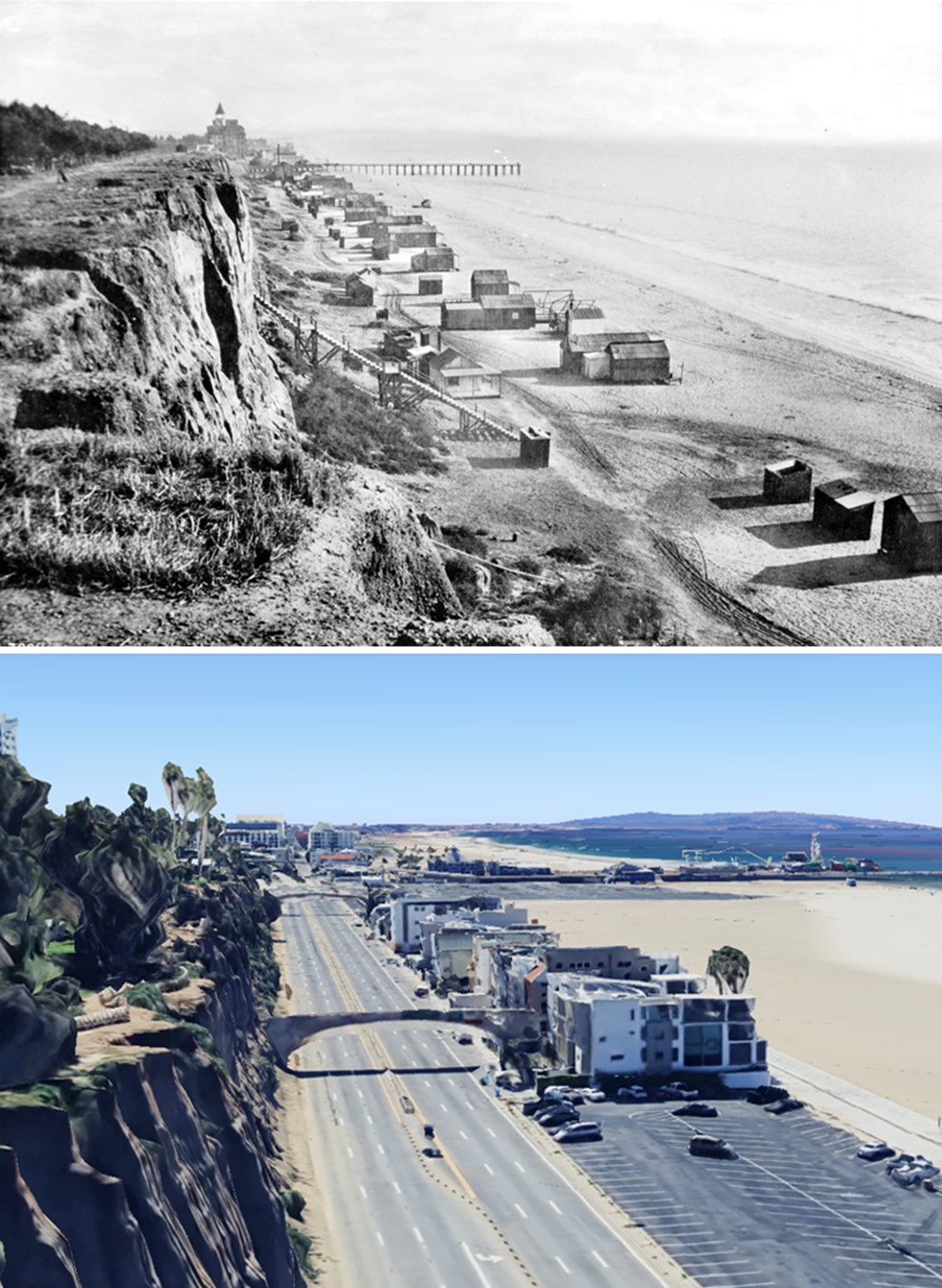

| (1877 vs. 2015)* – The coastline as seen from the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Wharf and today’s Santa Monica Pier. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes Today, the Santa Monica Pier is located slightly south of the original wharf built by the Los Angeles Independence Railroad Co. in Santa Monica, also known as Shoo Fly Landing. For better perspective, the two piers are aligned in this Then and Now image. The larger building atop the bluffs in the earlier photo is the Santa Monica Hotel, built in 1877 and situated on Ocean Avenue between Railroad Street (now Colorado Avenue) and Oregon Avenue (now Santa Monica Boulevard). The contemporary image highlights a much wider beach, primarily due to human intervention through beach nourishment projects. Over 30 million cubic yards of sand have been added, sourced from infrastructure developments and dredging operations. |

* * * * * |

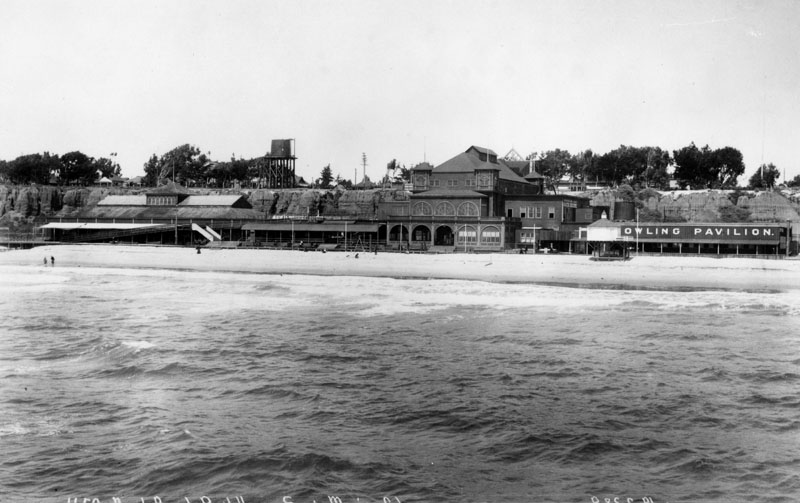

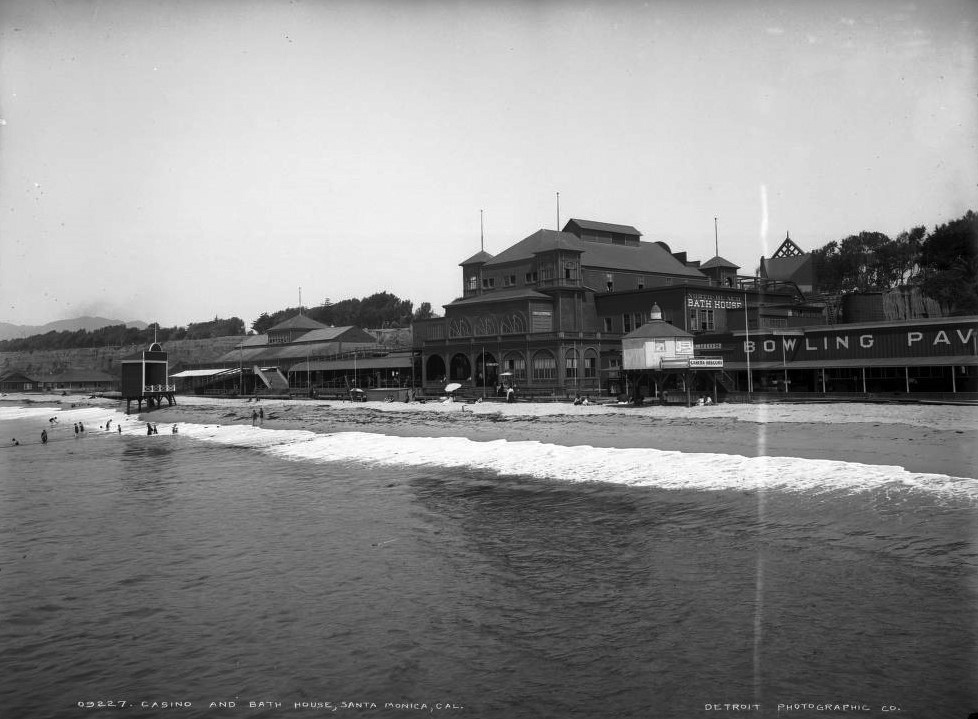

Santa Monica Beach and Bath Houses

|

|

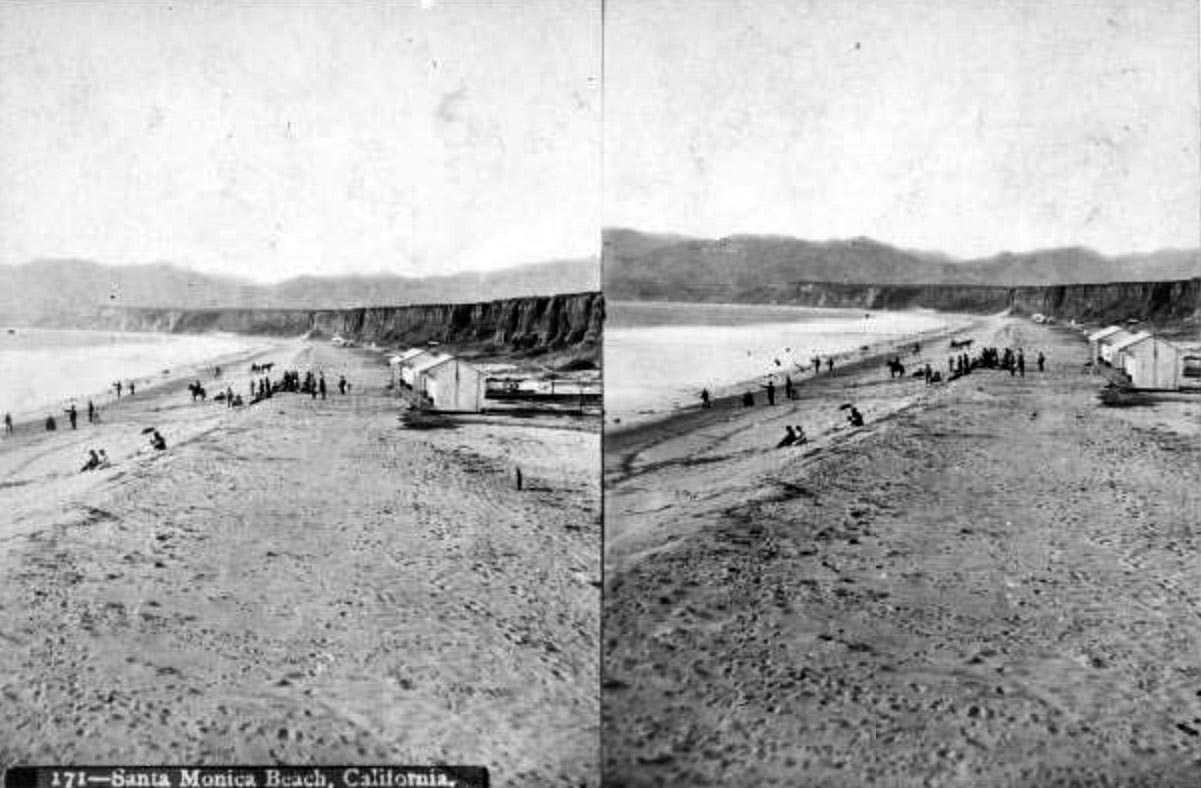

| (ca. 1876)* - Stereoscopic photo showing the beach in Santa Monica with beachgoers and buildings visible, including Michael Duffy's bathhouse visible in the background at the foot of the stairs along the Palisades cliffs. Note the horseback rider on the beach. |

Historical Notes Duffy’s Bathhouse, built in 1876 by entrepreneur Michael Duffy, was the first bathing establishment on Santa Monica’s beach. Located beneath the original Santa Monica Hotel at the base of the Palisades bluffs, it consisted of two simple structures housing 16 private rooms, each equipped with freshwater baths and showers—an uncommon amenity at the time. The facility operated until 1892 and played a foundational role in Santa Monica’s transformation from undeveloped coastline to a fashionable seaside retreat. |

|

|

| (ca. 1877)* - Stereoscopic photo of people sitting on a beach, dressed in suit coats and hats, in front of the Santa Monica Bath House. In the distance, a portion of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Wharf is visible, near the approximate site of today’s Santa Monica Pier. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes In 1877, Baker & Jones constructed the Santa Monica Bath House at the foot of Utah Avenue, just north of Duffy’s earlier structure. With steam baths, saltwater plunges, freshwater facilities, and rooms for rent, it was one of Southern California’s first purpose-built bathhouses. Its close proximity to the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Wharf made it especially accessible to Angelenos seeking oceanfront recreation, contributing to the rise of the North Beach district as a premier coastal destination. |

|

|

| (ca. 1877)* - Single (left-eye) view from the stereoscopic set showing Santa Monica’s early shoreline, with beachgoers in formal attire, a horseback rider, and the Santa Monica Bath House in the background. |

Historical Notes This left-eye panel from the 1877 stereoscopic image gives a clearer view of Santa Monica’s early recreational shoreline. The Santa Monica Bath House, built that same year, can be seen along with visitors arriving in their finest dress. The presence of the nearby railroad wharf helped turn what was once a quiet bluff-lined beach into a social and leisure hub for Los Angeles residents. |

|

|

| (ca. 1884)* - View showing the Santa Monica Bath House next to Duffy's Bathhouse on Santa Monica Beach. The long, two-story, barn-like bathhouse stands at center below the bluff, with a small residence perched above. Crowds of beachgoers are seen along the shoreline. |

Historical Notes By the 1880s, the two neighboring bathhouses—Duffy’s original 1876 facility and the larger 1877 Santa Monica Bath House—defined the city’s emerging North Beach area. The Santa Monica Bath House featured oversized bathtubs, steam rooms, and rentable rooms, reflecting a more structured and resort-like approach to seaside leisure. These early facilities laid the groundwork for Santa Monica’s rise as a prominent beach town. |

|

|

| (ca. 1885)* - View of the beachfront Santa Monica Bathhouse alongside Duffy's Bathhouse. At center-right can be seen the roofline of the new Santa Monica Hotel (built in 1877). Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes This image captures the peak of Santa Monica’s early bathhouse era. While Duffy’s modest operation was nearing its final years, the Santa Monica Bath House remained active into the late 1890s. Both were eventually surpassed by larger and more elaborate beachfront attractions like the North Beach Bath House (1894) and the Arcadia Hotel (1887), but their pioneering presence helped define Santa Monica’s coastal identity for decades to come. |

* * * * * |

Santa Monica Hotel

|

|

| (1877)* - Looking north toward the Santa Monica Hotel on Ocean Avenue, with railroad tracks visible in the foreground. A sign reading "Sea Shells" is painted on a building at right. A large gulch (ravine) sits between the hotel and the tracks. Photo by Carleton E. Watkins from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes The Santa Monica Hotel, built in 1877, holds the distinction of being the first hotel in the city of Santa Monica, California. It was located on Ocean Avenue between what are now Colorado Avenue and Broadway, perched atop the coastal bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Its prime location offered guests sweeping ocean views and easy access to the beach below, making it a popular destination for early travelers. |

|

|

| (1877)* – Closer view of the Santa Monica Hotel, located on Ocean Avenue between Colorado and Utah (now Broadway). Note the large gulch (ravine) forming the southern boundary of the hotel's property. |

Historical Notes The historic gulch (ravine) in Santa Monica closely corresponds to the site of today’s McClure Tunnel, which passes through the ocean bluffs beneath the intersection of Colorado Avenue and Ocean Avenue, near the Santa Monica Pier. Historically, the gulch separated the bluffs north and south of Colorado Avenue and was a major topographical feature. The original railroad tunnel (built in 1886) and the later automobile tunnel (opened in 1936) were both constructed here to span the ravine, which was eventually filled in to create the modern connection between the Santa Monica Freeway (CA-1/CA-2) and Pacific Coast Highway (PCH). |

|

|

| (2025)* – Google map showing the former location of the Santa Monica Hotel, which stood for only a decade before being destroyed by fire in 1887. |

Historical Notes The location of the historic gulch (ravine) in Santa Monica corresponds closely to the site of the present-day McClure Tunnel, which connects the Santa Monica Freeway (CA-1/CA-2) to Pacific Coast Highway (PCH). The McClure Tunnel passes through the Santa Monica ocean bluffs, directly underneath the intersection of Colorado Avenue and Ocean Avenue, and near the Santa Monica Pier. |

|

|

| (ca. 1885)* - Photograph of a view of the shore at Santa Monica taken from the Old Santa Monica Hotel. The balcony of the Old Santa Monica Hotel is visible in the left foreground while a long stable-style building stands surrounded with people in the distance. Horse-drawn carriages park and drive along the perimeter of a crescent of post-and-rail fence that demarcates a clearing at center behind which people are seated under a gazebo. Some kind of frame, possibly for the wall of a new building, has been erected to the far left. The ocean is visible in the background. |

Historical Notes At the time of the hotel’s construction, Santa Monica was a young and rapidly growing community, founded just two years earlier in 1875. The arrival of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad brought a steady stream of visitors and investors, creating a demand for accommodations. The Santa Monica Hotel met that need and quickly became a local social and recreational hub. Nearby, the city’s first bathhouse—built in 1876—added to the area’s appeal by offering freshwater baths and showers to guests and residents. A later image with a bridge built over the ravine that is visible in the center of this image is seen HERE. |

|

|

| (1885)* - A close-up view of the short-lived Santa Monica Hotel which burned down in 1887. |

Historical Notes At the time of the hotel’s construction, Santa Monica was a young and rapidly growing community, founded just two years earlier in 1875. The arrival of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad brought a steady stream of visitors and investors, creating a demand for accommodations. The Santa Monica Hotel met that need and quickly became a local social and recreational hub. Nearby, the city’s first bathhouse—built in 1876—added to the area’s appeal by offering freshwater baths and showers to guests and residents. It's worth noting that while the Santa Monica Hotel was the first proper hotel in the town, there were earlier accommodations for visitors. For instance, in 1876, Michael Duffy constructed what is believed to be Southern California's first beachside bathhouse, which included 16 rooms with freshwater baths and showers. However, this was not considered a full-fledged hotel in the same sense as the Santa Monica Hotel. |

|

|

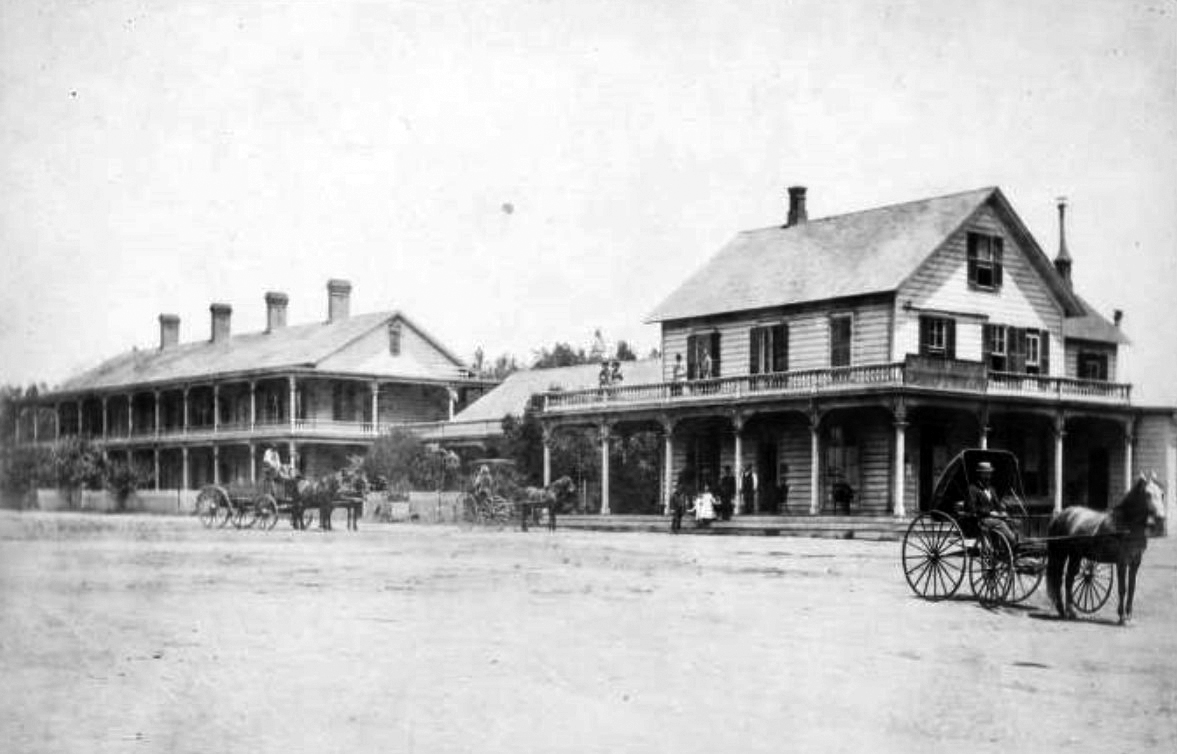

| (ca. 1885)* - View showing the Santa Monica Hotel on Ocean Avenue with horse-drawn wagons and buggies in front and people standing on the porch and balcony. The larger back building housed the sleeping quarters, the front building had offices and the dining room. |

Historical Notes The Santa Monica Hotel helped shape the city’s early identity as a destination for leisure and tourism. Its legacy endures in Santa Monica’s continued status as a vibrant, world-renowned coastal retreat, and it remains an important chapter in the city's rich and colorful history. |

|

|

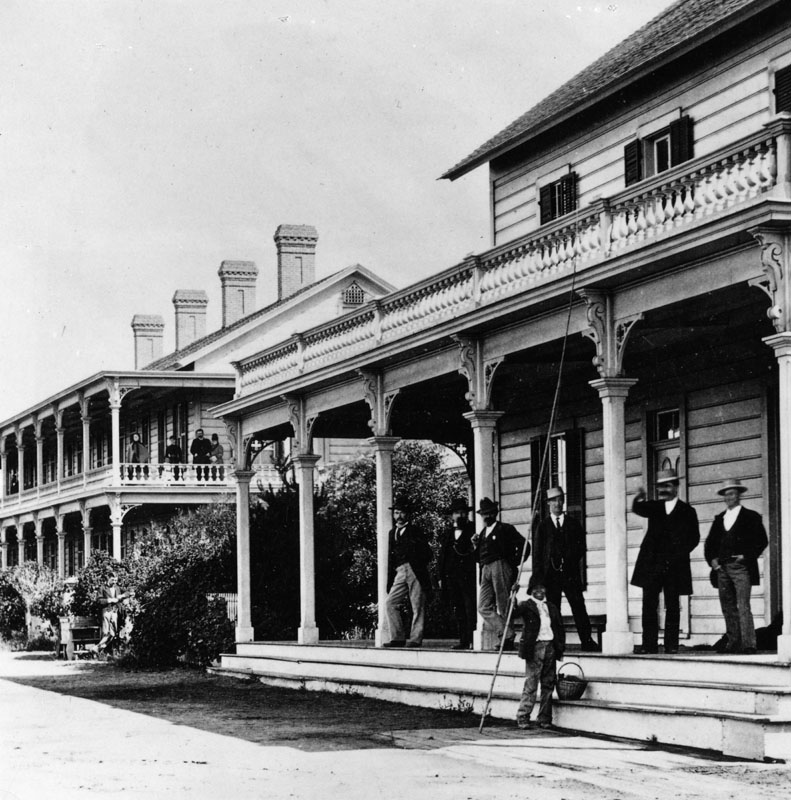

| (1885)* - A clearer image of the Santa Monica Hotel showing several people standing on the porch. |

Historical Notes Unfortunately, the Santa Monica Hotel's existence was short-lived. It burned down in 1887, just ten years after its construction. In the same year, a new hotel called the Arcadia Hotel was built near the site of the original Santa Monica Hotel. The Arcadia Hotel was a more luxurious establishment, featuring 125 rooms and the latest amenities of the time. |

|

|

| (1885)* - An even closer view of the Santa Monica Hotel with what appears to be hotel guests standing on the porch and balcony looking toward the photographer. |

Historical Notes The hotel served Santa Monica for a decade before being destroyed by fire in 1887. Its owner, J.W. Scott, responded by building the larger and more luxurious Arcadia Hotel on a nearby site, which would go on to become a celebrated coastal landmark. Though its lifespan was brief, the Santa Monica Hotel played a key role in establishing the town’s reputation as a seaside resort. |

* * * * * |

Duffy's and Santa Monica Bathhouses

|

|

| (ca. 1877)* - View looking at the shoreline from near the end of the Los Angeles and Independence Wharf with the Santa Monica Hotel on the Palisades and the Santa Monica Bathhouse on Sunset Beach between Colorado and Utah (now Broadway). |

Historical Notes The first bathhouse on Santa Monica’s beach was built by Michael Duffy beneath the Santa Monica Hotel in 1876 and had 2 structures with 16 rooms with their own freshwater bath and shower. It closed in 1892. |

|

|

| (ca. 1877)* - Image of people on the beach in front of the Santa Monica Bath House and Michael Duffy's Bath House (two long one-story buildings at right of the two-story Santa Monica Bath House) with the Santa Monica Hotel on the bluffs at right and the Ocean House on the bluffs among the trees at far left. |

Historical Notes During the ensuing years several other bathouses were built at the same site. Bathouses, featuring hot saltwater baths, were a big tourist draw to Santa Monica in the late 1800s and early 1900s. |

|

|

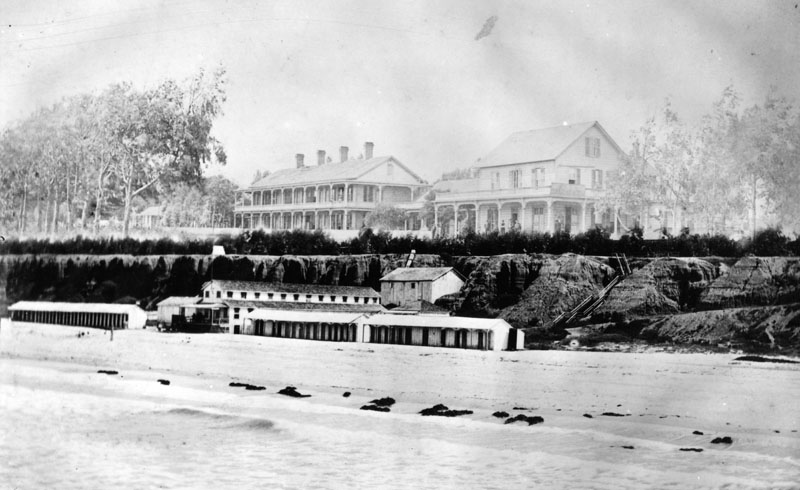

| (ca. 1880)* - The Santa Monica Hotel can be seen on the Palisades, which overlooks the beach at Santa Monica. Several people are standing or sitting on the veranda of the building on the right. A stairways (right) gives easy access from the Palisades to the beach. The two single-story structures in the lower center are Santa Monica beach's first bathouses. |

Historical Notes In 1887 the Santa Monica Hotel burned down. That same year the owner of the former Santa Monica Hotel, J. W. Scott, constructed a massive new hotel, the Arcadia Hotel. It was located near the site of the original Santa Monica Hotel at the corner of Ocean Avenue between Colorado and Pico Boulevard. The luxurious Arcadia Hotel had 125-rooms and featured the latest amenities. |

* * * * * |

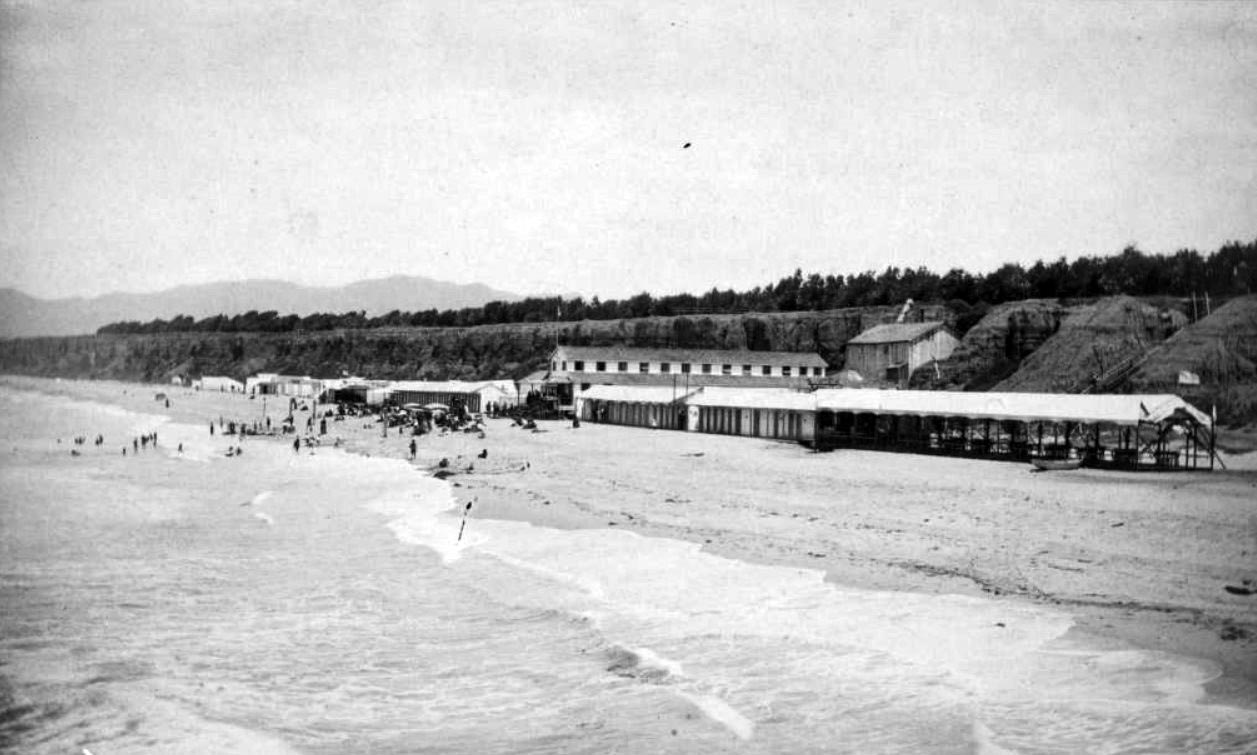

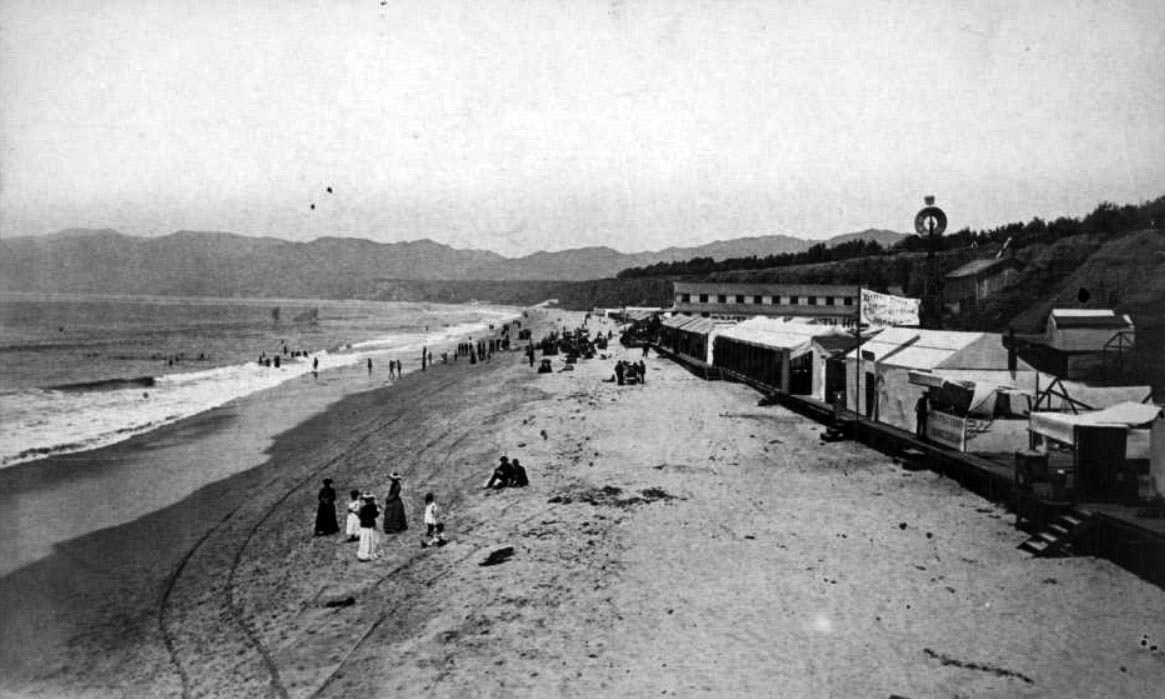

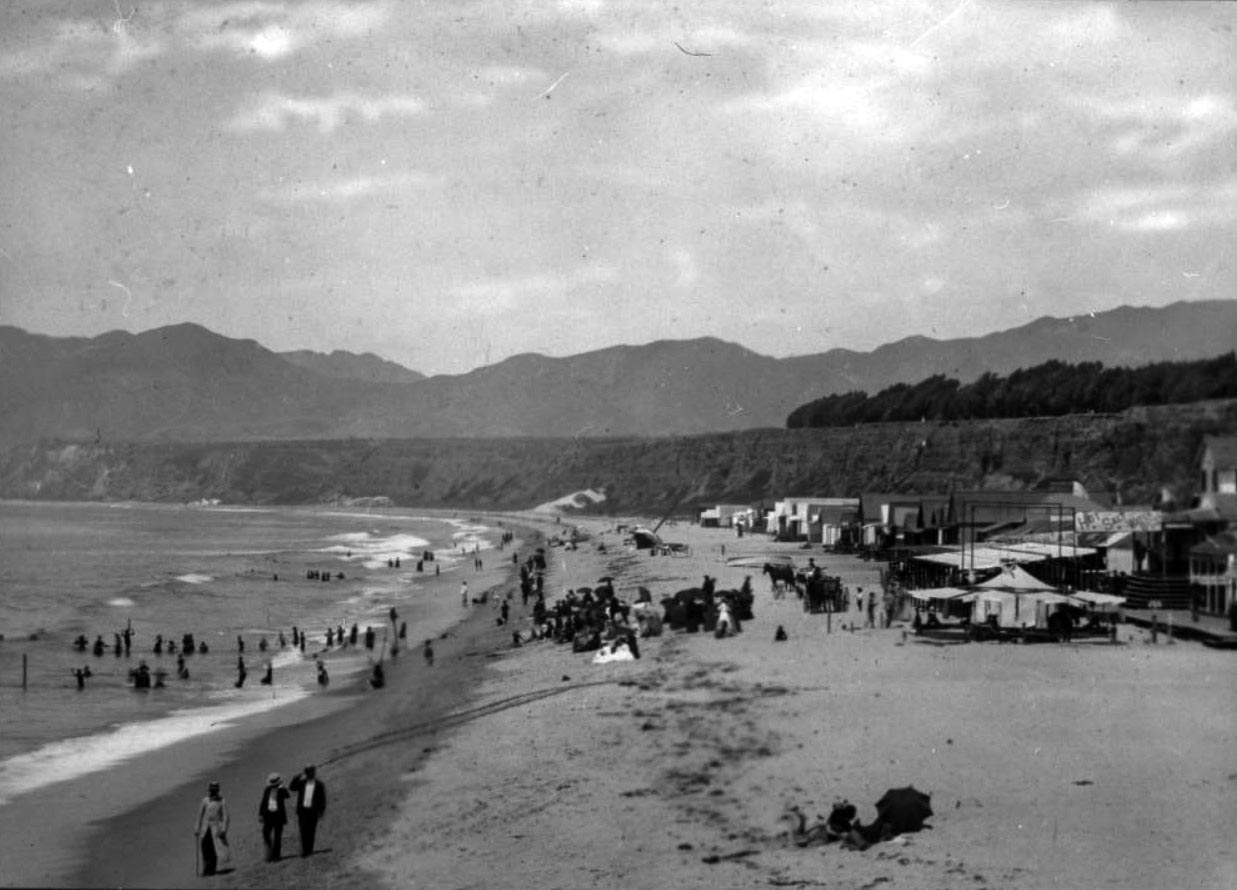

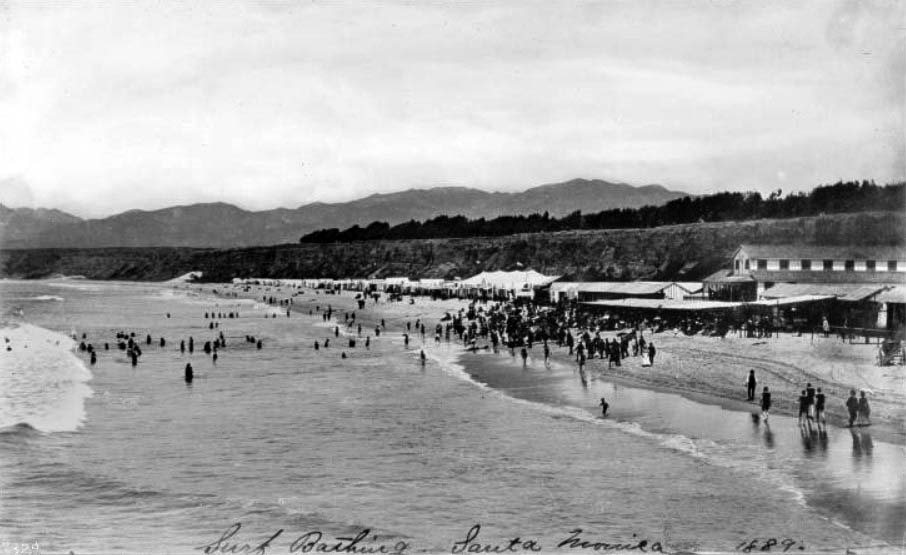

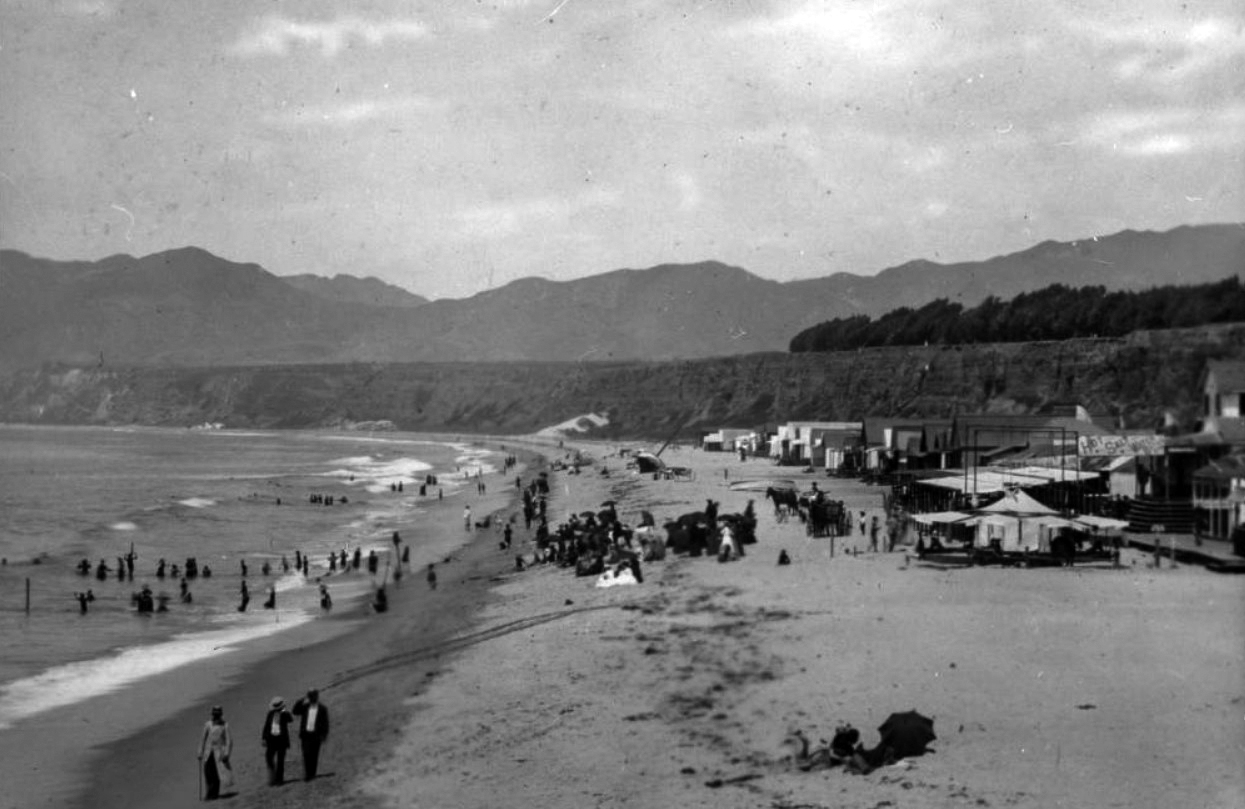

Santa Monica Beach

|

|

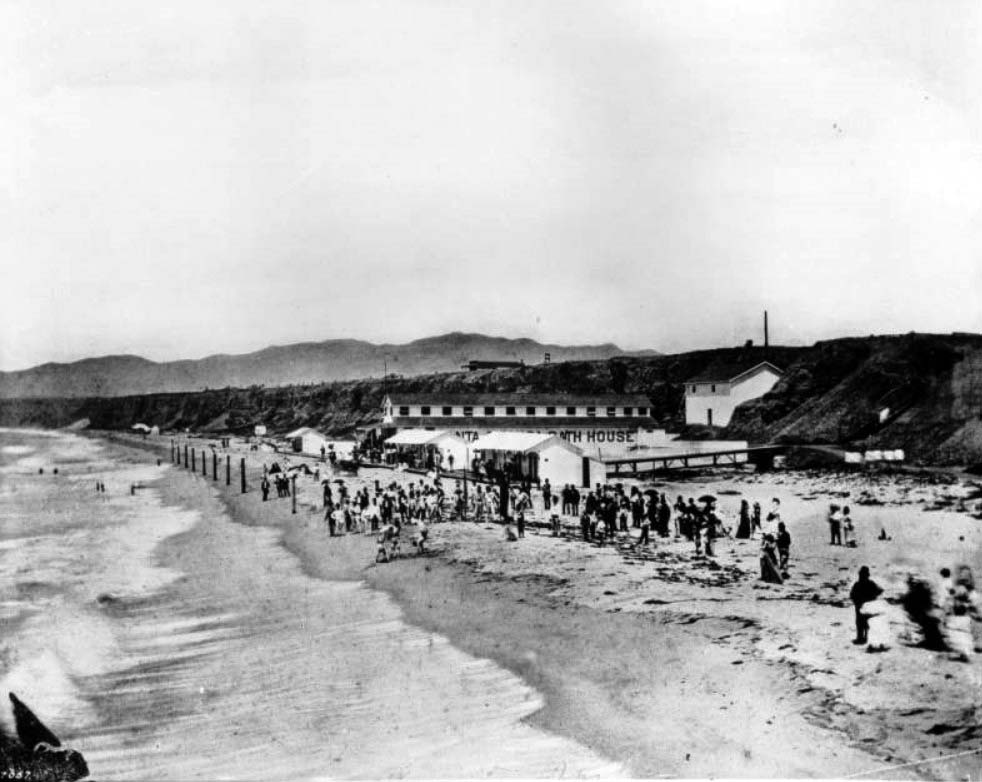

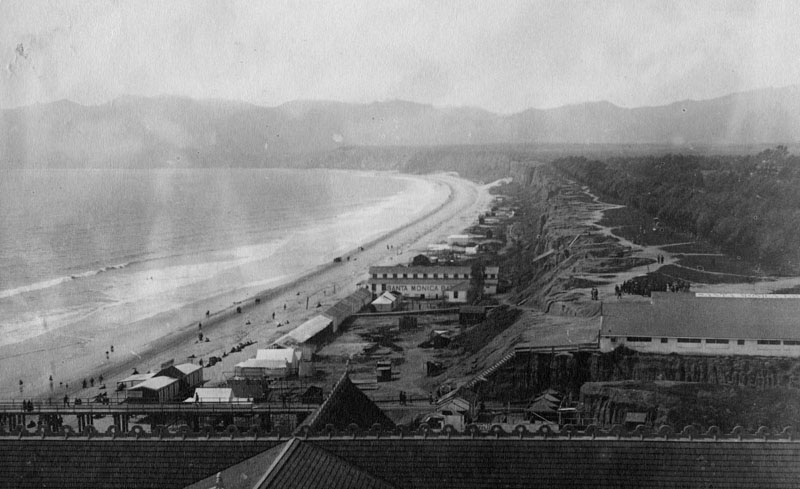

| (1880)* - Image of people on the beach in front of the Santa Monica Bath House and Michael Duffy's Bath House (two long one-story buildings at right of the two-story Santa Monica Bath House) with the Santa Monica Hotel on the bluffs at right and the Ocean House on the bluffs among the trees at far left. |

Historical Notes lIn the 1880s, Santa Monica's North Beach area already boasted several bath houses, setting the foundation for its reputation as a popular seaside resort. The trend began in 1876 when Michael Duffy constructed what is believed to be Southern California's first beachside bathhouse, featuring 16 rooms with freshwater baths and showers. The following year, the Santa Monica Bath House opened adjacent to Duffy's establishment, offering additional amenities such as steam baths and a saltwater pool. This bath house, built by Baker & Jones at the foot of Utah Avenue, continued to operate throughout the 1880s, as evidenced by images from that period. The area's popularity further increased with the opening of the Arcadia Hotel in 1887, which provided its guests with access to a large saltwater bathhouse. While these early facilities were not as grand as the famous North Beach Bath House that would be built in 1894, they played a crucial role in establishing Santa Monica's North Beach as a sought-after destination for beachgoers and tourists during the 1880s. |

|

|

| (1880s)* - View showing people on the beach and in the surf in front of the Santa Monica Bath House in Santa Monica, with trees on the bluffs above. A group of women in plain clothes are standing in the foreground. There is a boardwalk near the shops with signs that read "Coffee and Ice Cream Parlor" and "Fruits, Candies, Lemonade, Cigars." A windmill is visible behind the buildings. |

|

|

| (ca. 1880)* - Image of people on the beach and in the ocean in front of the Santa Monica Bath House, with sign "Hot Salt Water" and beach houses in Santa Monica, with a horse-drawn wagon at center. |

|

|

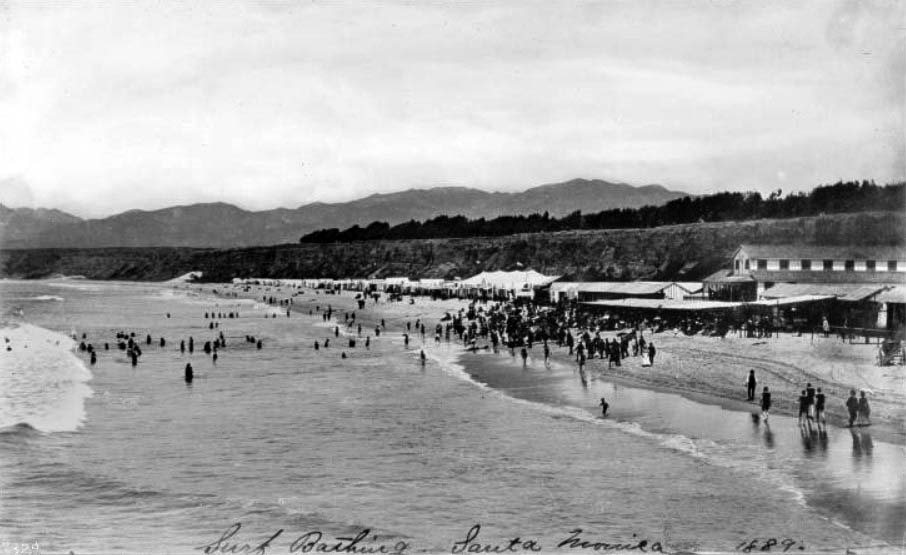

| (1889)* - Photograph of people at the shore on Santa Monica Beach. Beach houses and vendor's tents stand along the back end of the beach while a crowd of people moves into the surf at left from the shore. Mountains and trees can be seen above the cliff side in the background. Written-in text on the bottom of the image reads "Surf Bathing at Santa Monica". The Santa Monica Bathhouse is seen on the right. |

Historical Notes The above photo was taken from the L.A. & I. wharf. The Los Angeles and Independence Railroad (L.A. & I.) built a wharf in Santa Monica that opened in 1875, located near the present-day foot of Colorado Avenue, just north of where the Santa Monica Pier stands today. This original structure—also known as "Shoo Fly Landing"—was approximately 1,700 feet long and extended into waters 30 feet deep at low tide. Historical records confirm that the Santa Monica Pier is situated slightly south of the original wharf site. The L.A. & I. operated the wharf briefly before selling it, along with the railroad, to the Southern Pacific Railroad Company in 1877. By 1888, Southern Pacific had deemed the wharf unsafe for train operations and dismantled most of it, leaving behind only a shorter section or "stub" that remained in place until at least 1898. |

|

|

| (2022)* - View looking north from Santa Monica Pier showing about the same area as seen in previous photo. Photo courtesy of Davidus Vũdoo. |

Historical Notes The above photo was taken from the Santa Monica Pier which is situated slightly south of the original Los Angeles and Independence Rairloar wharf from where the previous photo was taken. |

Then and Now

|

|

.jpg) |

|

| (1889 vs. 2020)* - Santa Monica Beach. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes The bluff lines don’t match up exactly because the 1889 photo was taken from the old Los Angeles and Independence Railroad (L.A. & I.) wharf, which was closer to shore than the current view from the Santa Monica Pier, located slightly south of the original wharf. The beach is also much wider today—mainly because sand was added over the years through beach nourishment projects. More than 30 million cubic yards came from construction and dredging work. |

* * * * * |

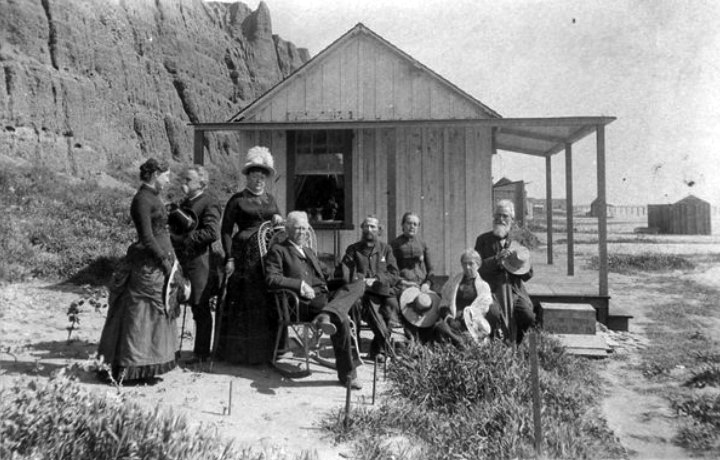

Santa Monica Canyon

|

|

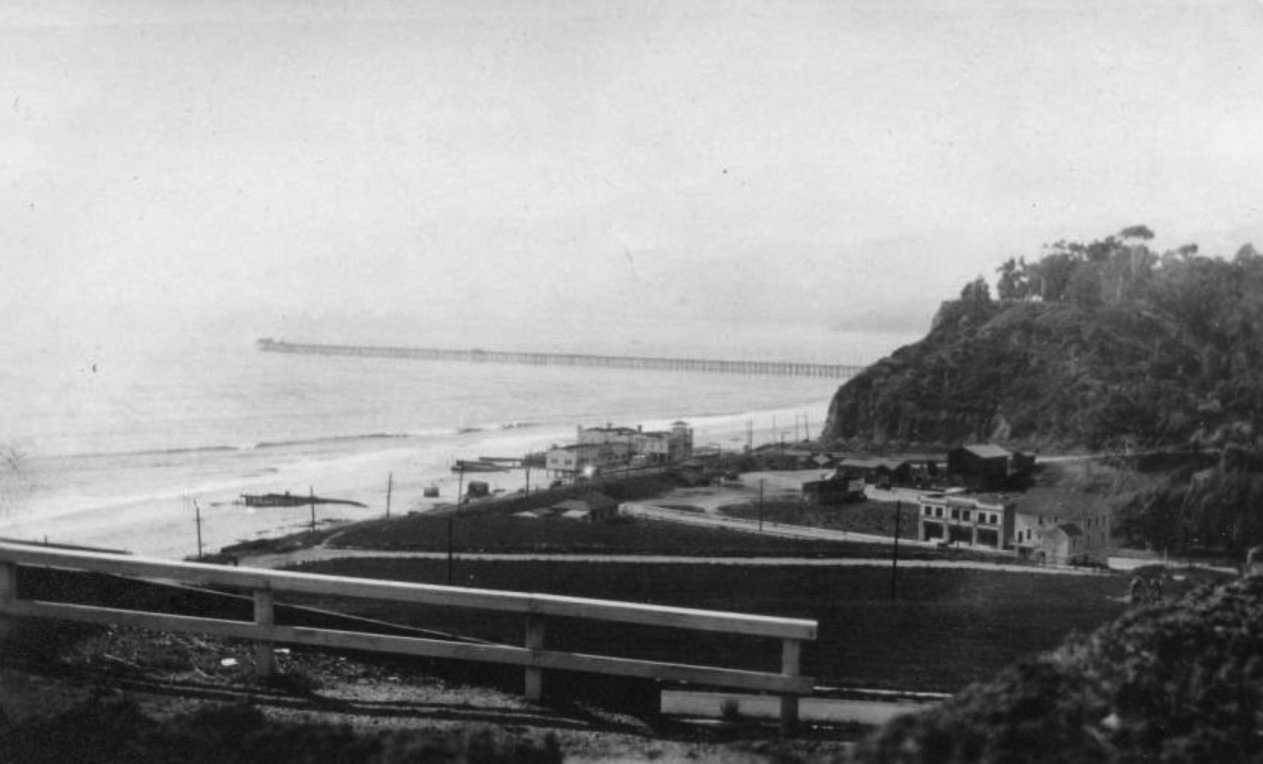

| (1900)#^- Panoramic view of the coastline and Santa Monica Canyon. |

|

|

| (1880s)* - View of the mouth of the Santa Monica Canyon, originally part of the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica (mouth of the Santa Monica). |

Historical Notes In 1769, Francisco Reyes journeyed to Alta California to help establish Franciscan missions and claimed the land for Spain. Soldiers gave the name Santa Monica to a mountain creek that flowed to the Pacific. |

|

|

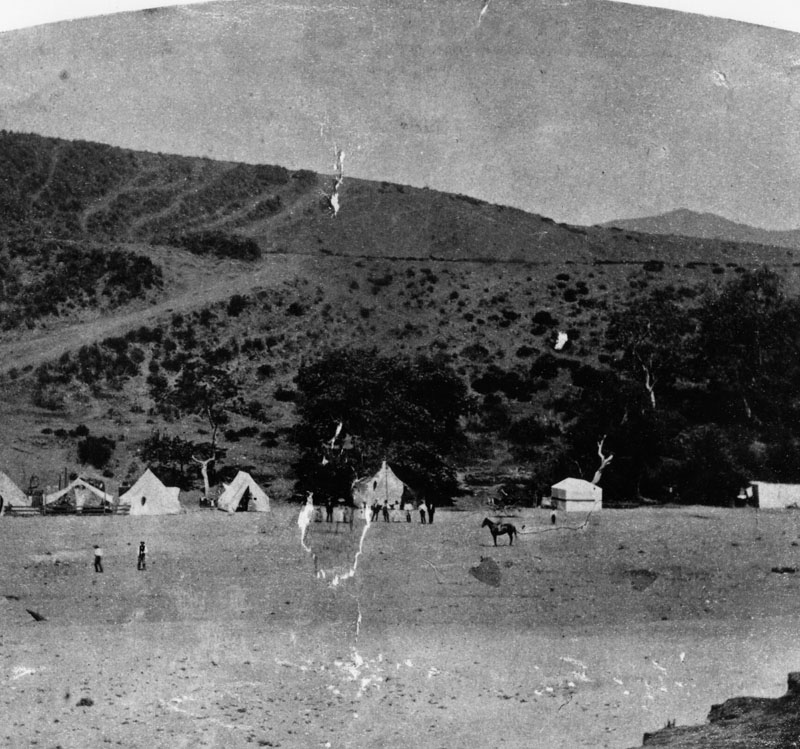

| (1880s)* - View of the mouth of the Santa Monica Canyon showing tents along the north canyon walls and on the beach. |

Historical Notes During the second-half of the 19th-century, the canyon was known as a camping area and rustic retreat near the beach hotels and resorts of nearby Santa Monica. |

|

|

| (1880s)* - Near the mouth of the Santa Monica Canyon showing the summer camps in the 1880s. A man can be seen sitting on a horse. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890s)* - View of a campground located on the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica in Santa Monica Canyon, which once belonged to the Marquez Family. The family allowed visitors throughout the Los Angeles area to camp there and enjoy the scenery and the cool ocean breezes. |

Historical Notes In the late 1880s, Abbot Kinney, the developer best known for designing the nearby community of Venice to the south, established an experimental forestry station and planted eucalyptus trees, for which the canyon is still known today. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890s)* - People in folk costumes are camping in tents in Santa Monica Canyon probably in the 1890s. |

Historical Notes Despite the challenges of Mother Nature, the beauty and peace of The Canyon began attracted near-by Angelenos. A small grocery store sold fresh produce and items from the local Rancheros and small tents dotted the mouth of The Canyon for picnicking and camping. |

* * * * * |

Marquez Adobe

|

|

| (1900)* - Exterior of the Pascual Marquez adobe built about 1845 on the Boca de Santa Monica rancho. The adobe appears delapidated now. |

Historical Notes After Mexico won its independence from Spain, Francisco Reyes' grandson Ysidro and his neighbor, Francisco Marquez, were granted 6,656 acres of the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica (mouth of the Santa Monica). They built the area's first permanent structures. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* - Image of the adobe house built by Pascual Marquez located in Santa Monica Canyon. Ernest Marquez Collection |

Historical Notes Remarks from donor Ernest Marquez, 2015: "The adobe house was built by my grandfather Pascual Marquez in 1875, about 75 yards from the adobe where he was born, built by his father Francisco in 1839. I think Pascual’s adobe collapsed in an earthquake in the 1930s." |

* * * * * |

Marquez Bath House

|

|

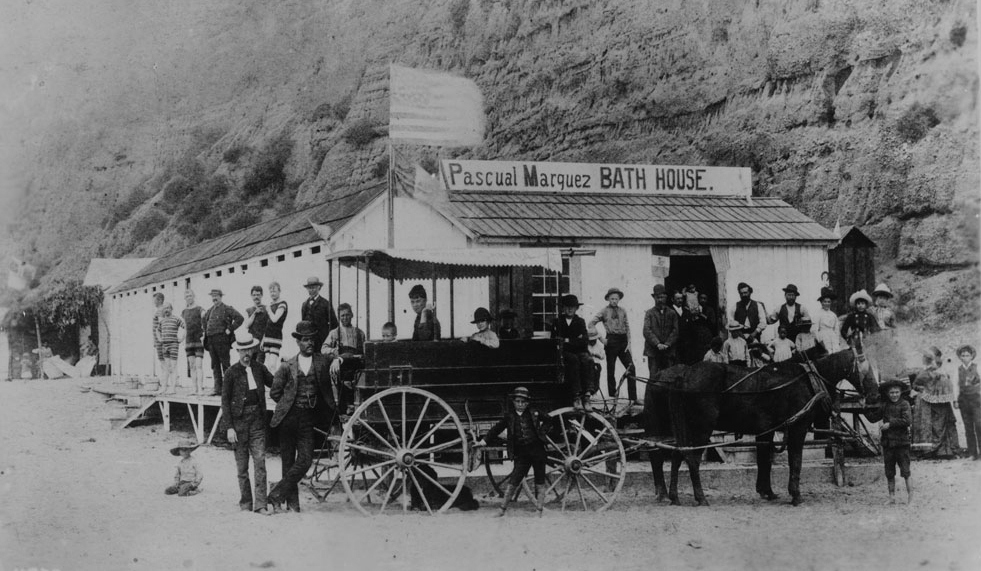

| (ca. 1887)* - Photograph of a group of about 30 people (men, women and children) posing in front of Pascual Marquez's bath house -- the first bath house in Santa Monica Canyon. A stagecoach -- the Santa Monica Canyon State -- drawn by a two-horse team stands in front. An American flag flies from the roof of the single-story wood structure. The nearly vertical rocky canyon wall looms behind. A sign on the roof reads "Pascual Marquez bath house". |

Historical Notes These type of horse-drawn wagons transported visitors from Los Angeles to Santa Monica before the arrival of train service to the area. |

* * * * * |

First Stage and Mail Service

|

|

| (ca. 1880s)^ - First stage and mail service operated in 1880s between Santa Monica and Topanga Canyon. |

Historical Notes The 1st mail wagon was established by "Aunt Lucy" Cheney and began service in 1880. It provided mail service between Santa Monica and Topanga Canyon. They began to carry passengers (as shown here) in 1885. Also pictured is "Uncle Mose" Cheney.* |

* * * * * |

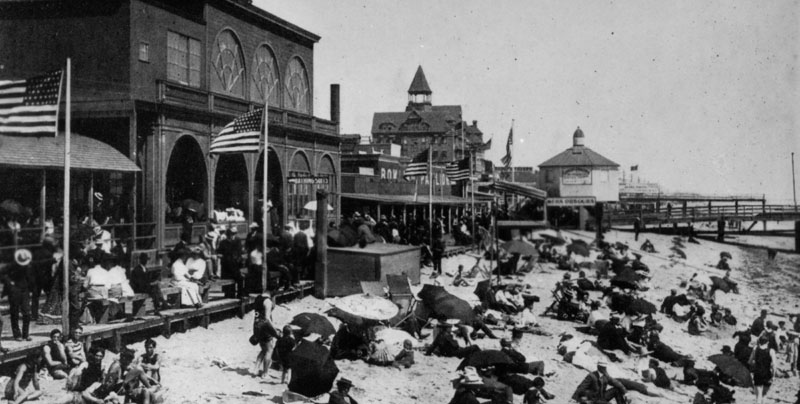

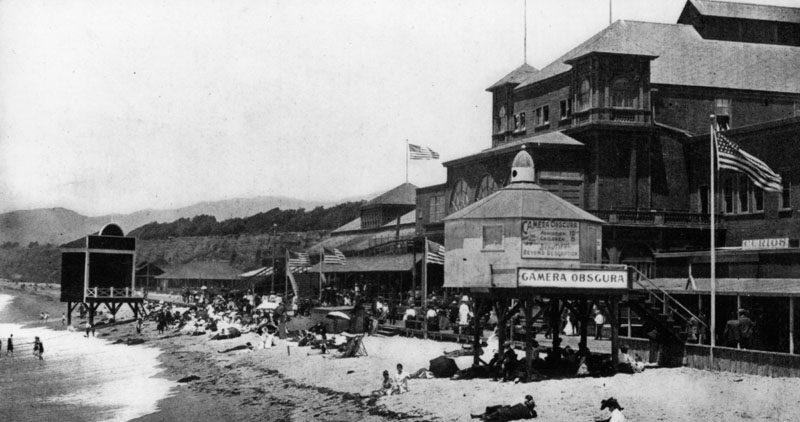

Early Santa Monica Beach Views |

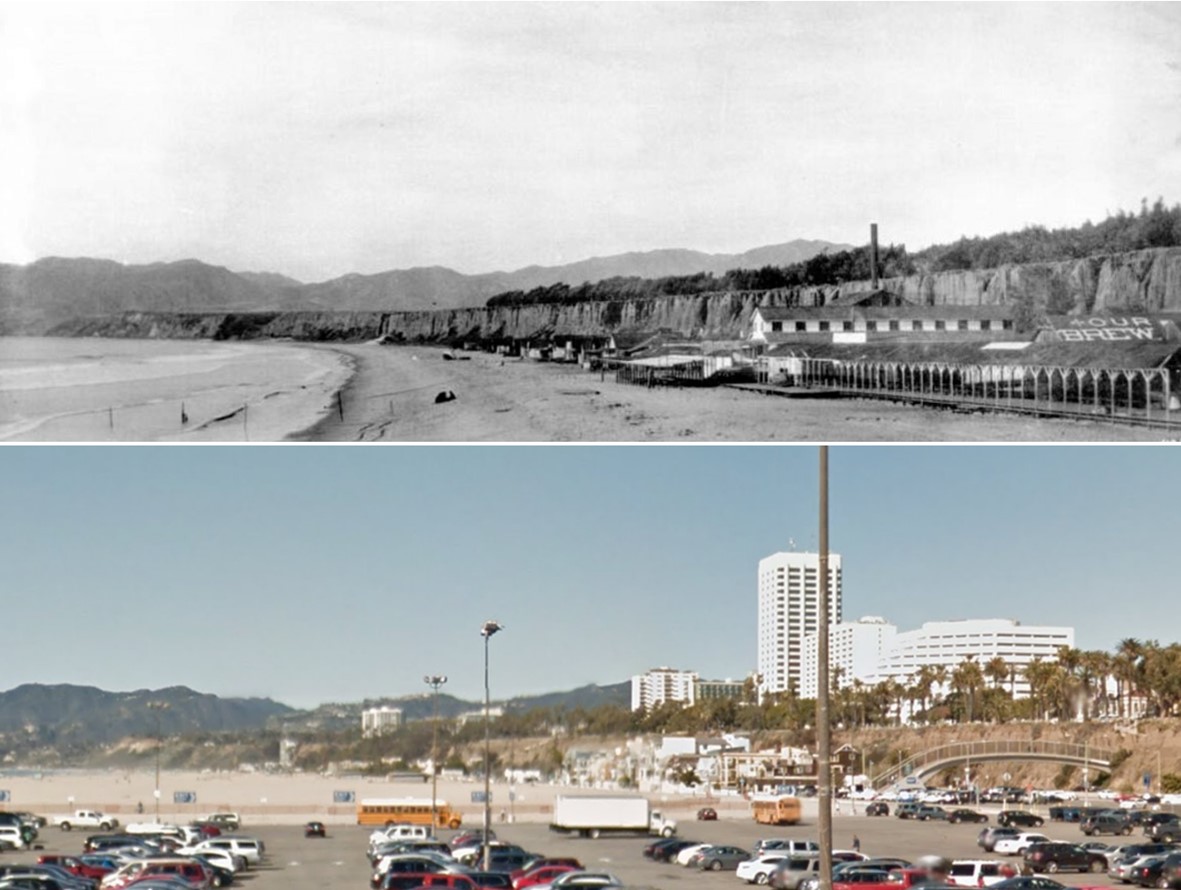

In the late 1880s, Santa Monica was transforming from a quiet coastal outpost into one of Southern California’s first true seaside resorts. What made this transformation possible was not just the ocean, but transportation, investment, and vision. Railroads brought thousands of visitors from Los Angeles. Entrepreneurs built bath houses and hotels. Promoters advertised fresh air, saltwater bathing, and scenic beauty.

|

|

|

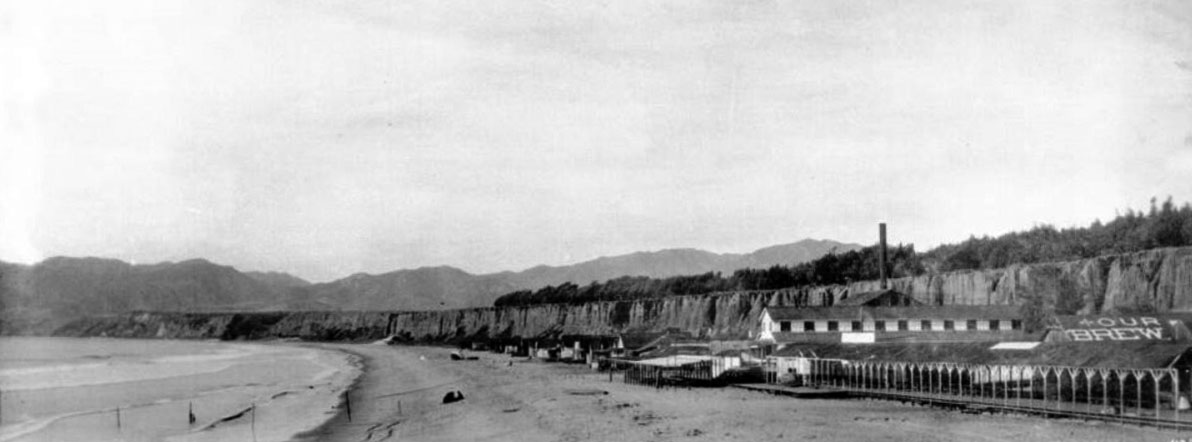

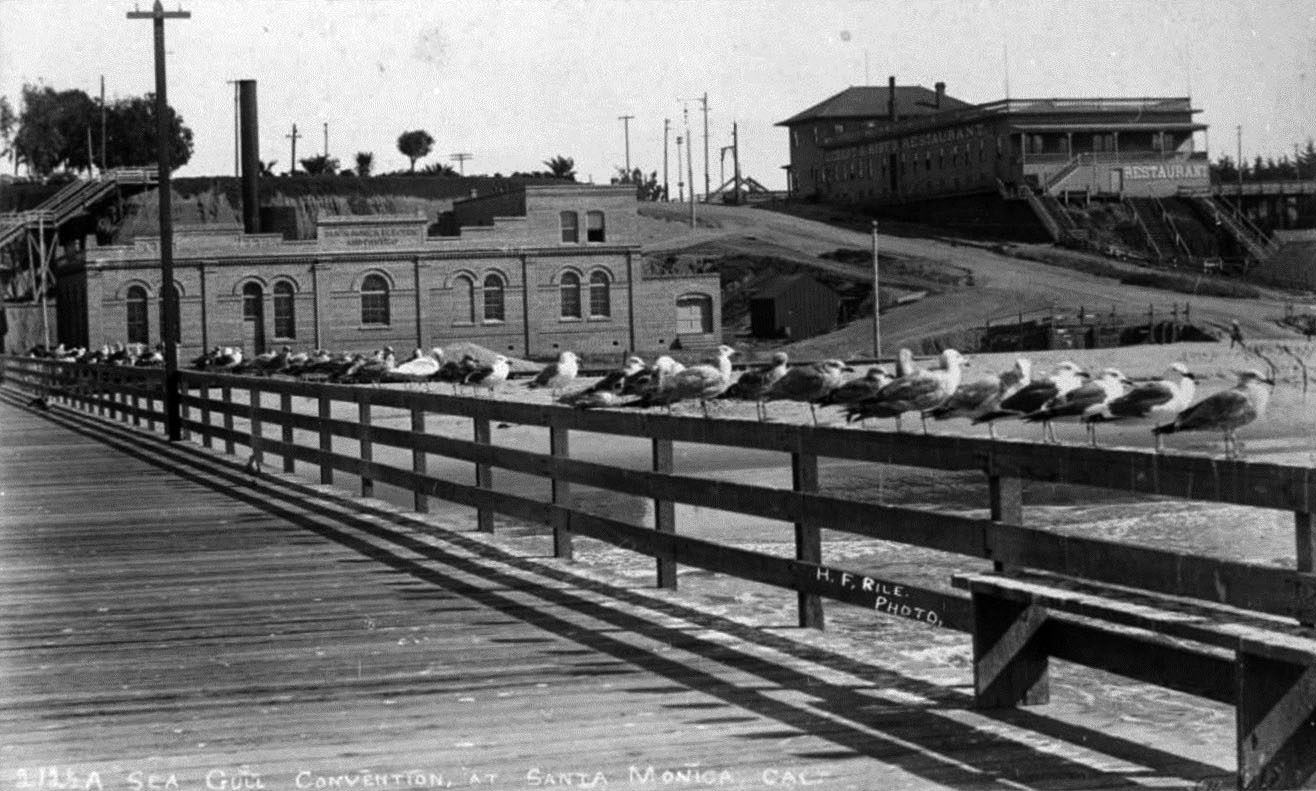

| (ca. 1887)* – Panoramic view showing the old Bath House looking north at North Beach, Santa Monica. The beach is mostly deserted except for a small group of people. A long covered boardwalk runs along the front of the bath house, and a tall smokestack rises above the structure. A rooftop sign reads “Our Brew.” |

Historical Notes North Beach emerged as a popular destination in the 1880s. Its success was closely tied to the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad, controlled by U.S. Senator John P. Jones. The railroad made it possible for residents of Los Angeles to reach the ocean quickly and affordably. By the late 1880s, thousands of visitors were arriving daily during the summer months. The bath house facilities of this era offered changing rooms and saltwater bathing, which was believed to promote good health. These early structures laid the foundation for the larger and more elaborate North Beach Bath House built in 1894, designed by architect Sumner P. Hunt and financed by Senator Jones. |

|

|

| (ca. 1887)* – Panoramic view of Santa Monica Beach with the Palisades in the background. (AI image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff) |

Historical Notes This view shows the natural shoreline as it existed in the late 19th century. The beach was narrower and shaped entirely by coastal forces. There were no paved roads, no large public facilities, and no wide engineered sand areas. During the 20th century, tens of millions of cubic yards of sand were added to Santa Monica and Venice beaches through replenishment projects. The result is the much broader shoreline seen today. |

|

|

| (1880s)* - People on the beach and in the ocean in front of the Santa Monica Bath House, with sign “Hot Salt Water,” beach houses nearby, and a horse-drawn wagon at center-right. |

Historical Notes Ocean bathing became increasingly popular during the 1880s. Bath houses provided changing rooms and heated saltwater plunges, reflecting the belief that saltwater had health benefits. The “Hot Salt Water” sign advertised one of the main attractions of the facility. The presence of a horse-drawn wagon and visible carriage tracks in the sand reminds us that the beach also functioned as a roadway. Before automobiles, horses provided transportation both to and along the shoreline. |

|

|

| (1887)* - Santa Monica Beach looking north. The Palisades are visible in the background. |

Historical Notes By 1887, Santa Monica was firmly established as a seaside resort. Visitors came by rail to enjoy the fresh ocean air and open shoreline. The landscape remained largely undeveloped, with the Palisades rising prominently above the beach. This natural setting helped define Santa Monica’s early identity as a place of health, leisure, and scenic beauty. |

|

|

| (1887)* - Beachgoers walking and riding bicycles along the shoreline in Santa Monica. The Palisades rise at right, with the Santa Monica Mountains visible in the distance. Image lightly enhanced for clarity. Original HERE. |

Historical Notes Bicycles became popular in the late 19th century, and the firm sand near the shoreline provided an ideal surface for riding. The beach served not only as a bathing area but also as a public gathering space for walking, socializing, and recreation. The absence of automobiles and heavy development gives this scene a quiet, open character very different from the modern coastline. |

|

|

| (1890s)* – View showing people standing on the beach in bathing suits in Santa Monica. Horse and carriage tracks are visible in the sand. |

Historical Notes By the 1890s, beachgoing had become more common and more social. Bathing suits reflected Victorian standards of modesty, covering most of the body. The tracks left by horses and carriages show how people moved along the shoreline before the arrival of motor vehicles. These details help illustrate everyday life at the beach more than a century ago. |

|

|

| (1888)* - Beachgoers with a parasol on the sands of Santa Monica. The Arcadia Hotel and the remains of the Los Angeles and Independence Wharf appear in the distance. Image lightly enhanced for clarity. Original HERE. |

Historical Notes The Arcadia Hotel opened in 1887 and was the largest structure in Santa Monica at the time. It was owned by J. W. Scott and named for Arcadia Bandini de Baker, wife of Santa Monica cofounder Robert S. Baker. The hotel symbolized the city’s ambitions as a first-class resort destination. The Los Angeles and Independence Wharf once extended into the Pacific and supported both freight and passenger service. Together, the railroad and the wharf helped transform Santa Monica from a quiet coastal settlement into one of Southern California’s earliest beach resorts. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1887 vs. 2015)* – Panoramic view of Santa Monica Beach with what is now Palisades Park in the background. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes Although the camera angles differ slightly, the most noticeable change is the width of the beach. The shoreline today is far broader than it was in 1887. In the late 19th century, the beach was narrower and shaped entirely by natural coastal forces. Beginning in the 1940s, millions of cubic yards of sand were added to Santa Monica and Venice beaches through large-scale replenishment projects. These efforts were intended to reduce erosion, protect coastal development, and expand recreational space. The result is the wide, engineered shoreline seen today. Very different from the natural beach of the 1880s. |

* * * * * |

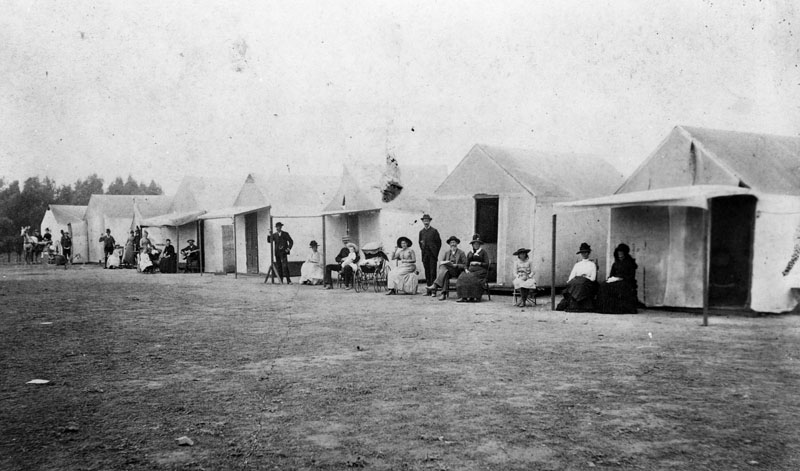

Early Santa Monica Cottages and House-Tents |

|

|

| (1888)* - Visitors to Santa Monica Beach in front of a beach cottage. The pier can be seen in the background with the Arcadia Hotel out of view behind the beach shack. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes In the 1880s and 1890s, North Beach in Santa Monica featured various temporary structures like house tents, beach cottages, vendor tents, and bath houses. House tents provided simple, affordable seaside accommodations, while small beach cottages offered more permanent lodging. Vendor tents and bath houses, including the Santa Monica and North Beach Bath Houses, provided amenities like refreshments and saltwater baths. These developments reflect Santa Monica's early growth as a beach resort, catering to the increasing demand for oceanfront leisure and recreation. |

|

|

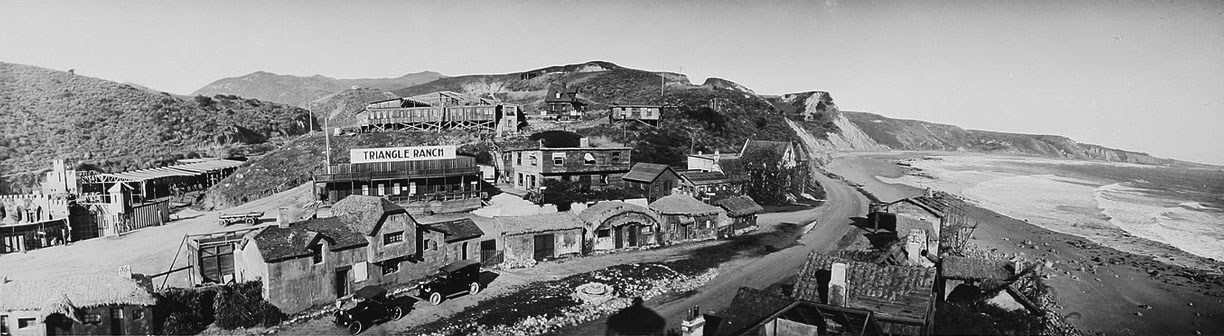

| (ca. 1887)* - View of Santa Monica beach looking south from Santa Monica Canyon rim. The newly constructed Arcadia Hotel can be seen in the background along with the remains of the Los Angeles & Independence Wharf. House-tents are seen along the beach. |

Historical Notes The Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Wharf was in use between 1875 and 1879, at which time it was partially dismantled. In 1898, a new pier would be built, North Beach Pier, just to the north of where the above wharf is seen. |

|

|

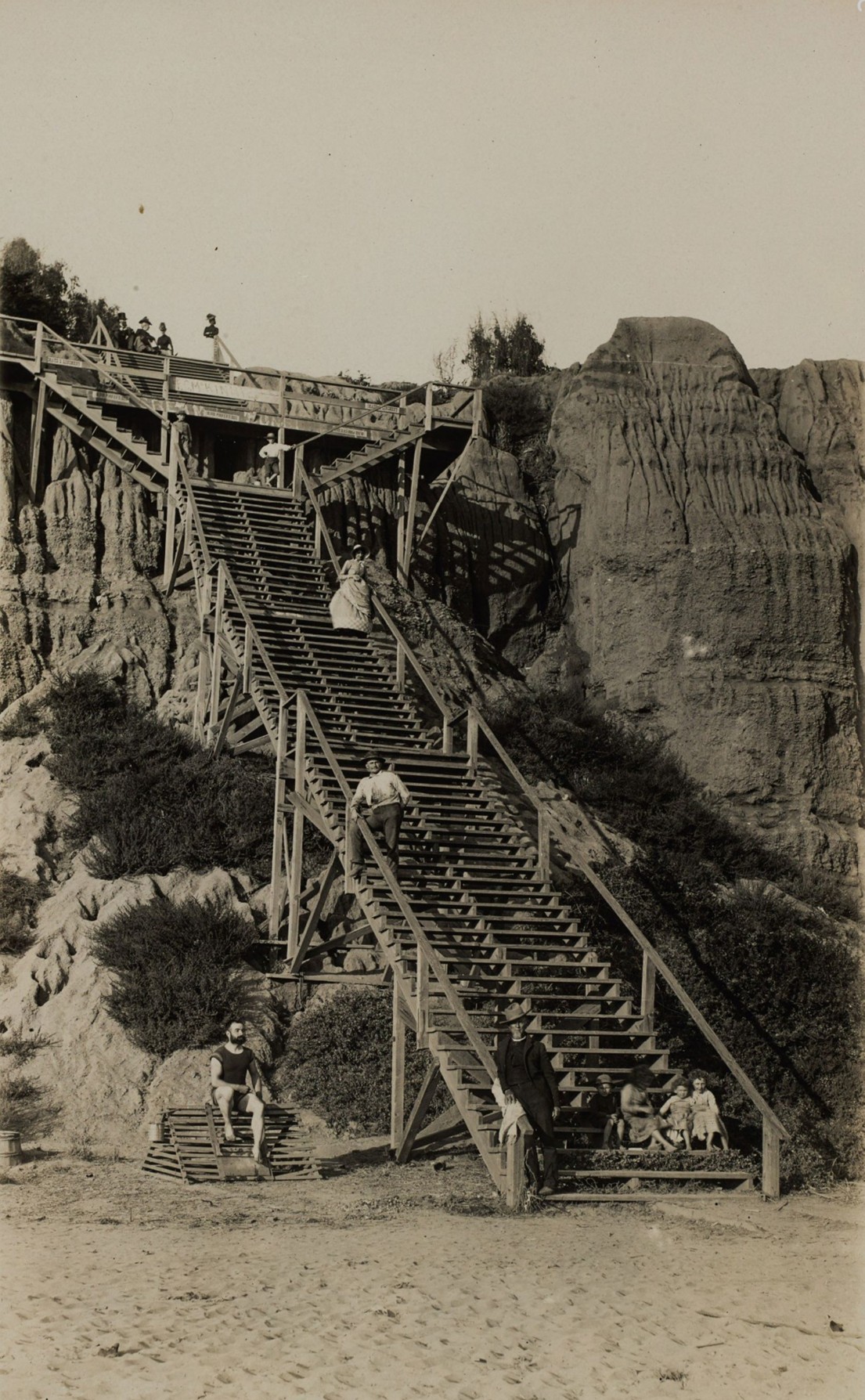

| (ca. 1889)** - Looking south from the '99 steps' toward the Arcadia Hotel. In the upper left can be seen a man sitting on a bench very close to the edge of the palisades (This area would become Palisades Park). The stub of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Wharf can also be seen. |

Historical Notes Originally known as “Linda Vista Park,” Palisades Park was the first officially-designated public open space in Santa Monica. The land was donated to the City by Santa Monica's founder, Senator John P. Jones, in 1892. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)^- View looking south from the rim of the Palisades, overlooking the original "99 Steps," which provided access to the northern portion of Santa Monica beach. Seen in the distance is the Hotel Arcadia and the stub of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Co. Wharf. The vantage point of this photograph is near the foot of Wilshire Avenue. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)^- View looking south from the rim of the Palisades, overlooking the original "99 Steps," which provided access to the northern portion of Santa Monica beach. Seen in the distance is the Hotel Arcadia and the stub of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Co. Wharf. The vantage point of this photograph is near the foot of Wilshire Avenue. AI image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff |

|

|

| (1891)* - View of North Beach looking south towards the Arcadia Hotel. Tent houses line the beach area. |

|

|

| (1893)* - View looking south showing North Beach and the Arcadia Hotel with the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks running next to the Beach Road in Santa Monica. The Santa Monica Bath House and the remains of the Los Angeles and Independence Wharf are visible at right and the Palisades Bluffs are visible at left. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

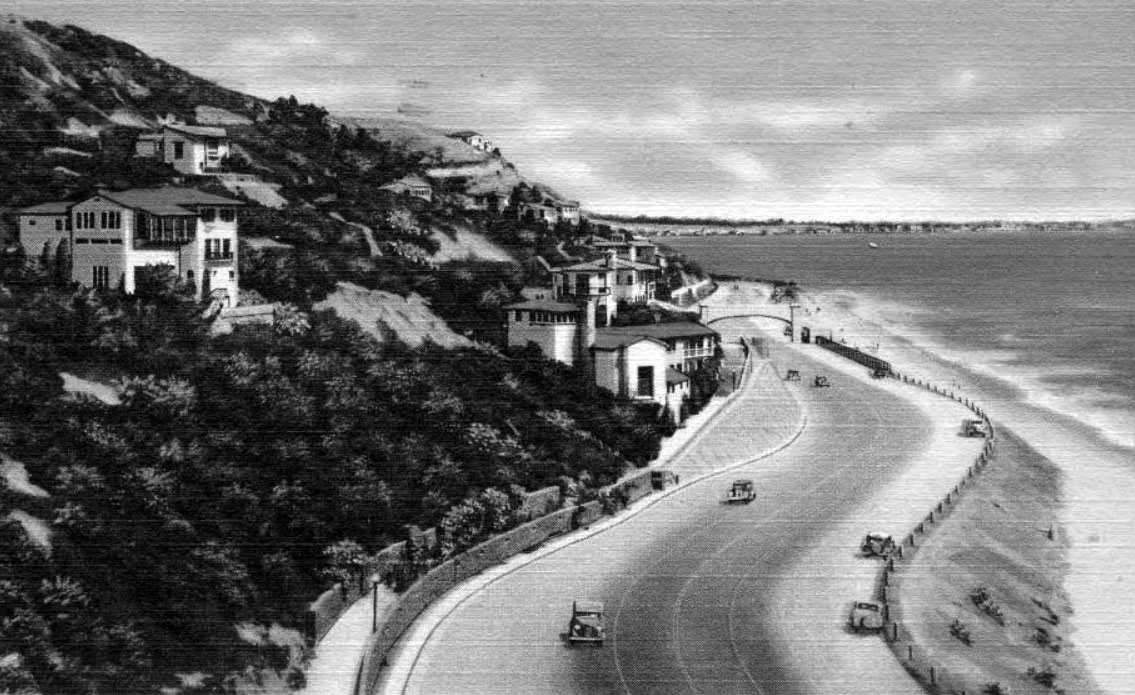

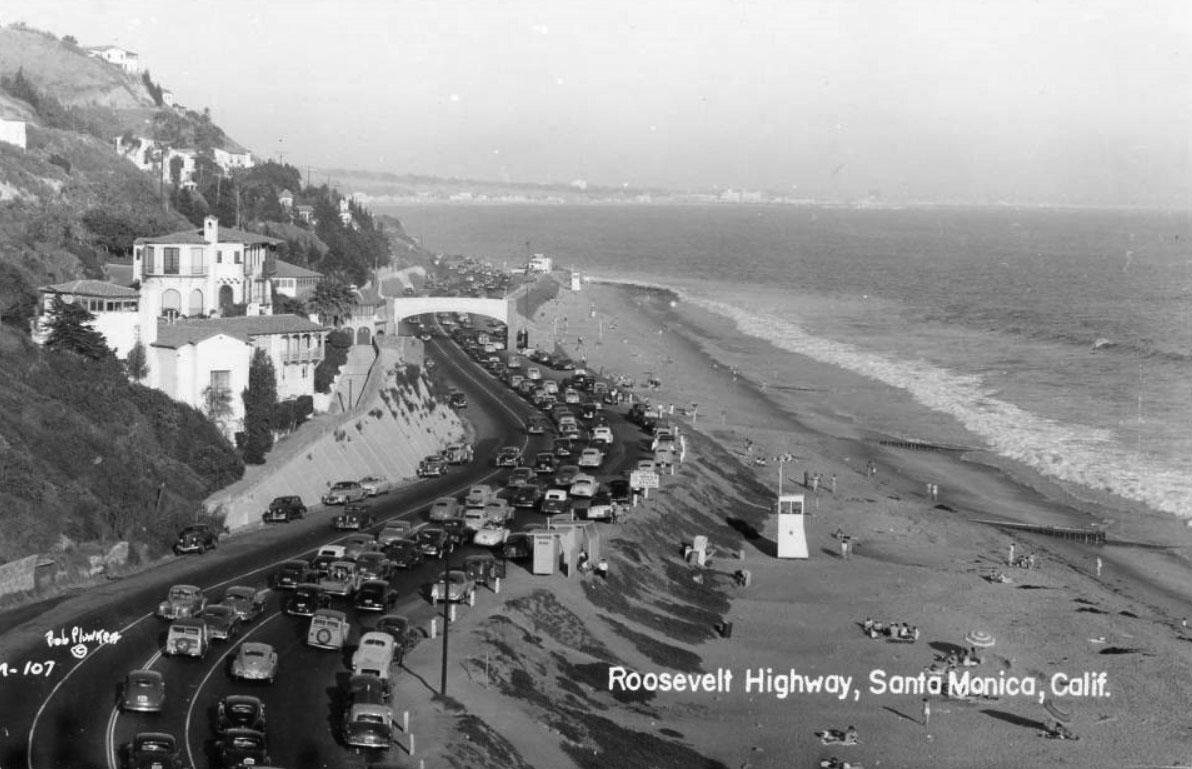

Historical Notes Tracks were first laid in Santa Monica in 1875 with the construction of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad. This steam-powered rail line connected Santa Monica to downtown Los Angeles, running from the Santa Monica Long Wharf north of the current Santa Monica Pier to 5th and San Pedro streets in Los Angeles. This line was intended to serve both freight and passenger purposes, facilitating the transport of mined ore and beachgoers. The Los Angeles and Independence Railroad was purchased by the Southern Pacific Railroad on July 1, 1877. In 1892, the Southern Pacific Railroad extended the existing tracks, seen above, to their new Long Wharf (completed in 1893) north of Santa Monica Canyon, enhancing the line's capacity to handle larger ships and increasing its importance for freight and passenger transport. Beach Road became Roosevelt Highway in Santa Monica in 1927. This change was part of a larger effort to develop the highway system along the California coast, and the Roosevelt Highway would later become known as the Pacific Coast Highway (PCH). The railroad tracks along Santa Monica Beach were in use from 1891 until 1933. It appears that the majority of beach shacks along Santa Monica's North Beach were removed with the laying of railroad tracks by Southern Pacific in 1892. No photos of these beach shacks have been found after 1892. |

|

|

| (ca. 1895)* - View of the Santa Monica seaside bluffs (Linda Vista Park, later Palisades Park). The Arcadia Hotel and Los Angeles and Independence Wharf - forerunner to today’s Santa Monica Pier - are both visible in the distance. |

Historical Notes Originally known as “Linda Vista Park,” Palisades Park was the first officially-designated public open space in Santa Monica. The land was donated to the City by Santa Monica's founder, Senator John P. Jones, in 1892. Linda Vista Park was renamed Palisades Park in the 1920s. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1890 vs. 2023)* – View looking south from the rim of what is now Palisades Park near the foot of Wilshire Boulevard. The 1890 photo shows the original "99 Steps," which provided access to the northern portion of Santa Monica Beach. In the distance, the Hotel Arcadia and the remains of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Co. Wharf are visible. The 2023 photo shows the Pedestrian Bridge, connecting the Palisades at the end of Arizona Avenue to the beach below, located at the site of the original "99 Steps" built in 1875. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes While the camera angles differ slightly, the contemporary image clearly shows more sand on the beach. This increase is largely due to human intervention, particularly through beach nourishment projects. Over the past century, efforts have been made to widen and enhance the beach to boost tourism and recreation. Key factors include adding approximately 30 million cubic yards of sand, sourced from infrastructure projects and dredging operations, and the desire to make Santa Monica Beach resemble the wider, flatter beaches of the East Coast. In 1947, for example, nearly 14 million cubic yards of sand were removed to make way for El Segundo's Hyperion power plant. They were deposited onto Santa Monica's beaches. Another million cubic yards came a couple years later, the sand this time recovered from dredging operations along a nearby breakwater. In all, some thirty million cubic yards of sand have been dumped onto the beaches of Santa Monica and Venice. |

* * * * * |

Arcadia Hotel

|

|

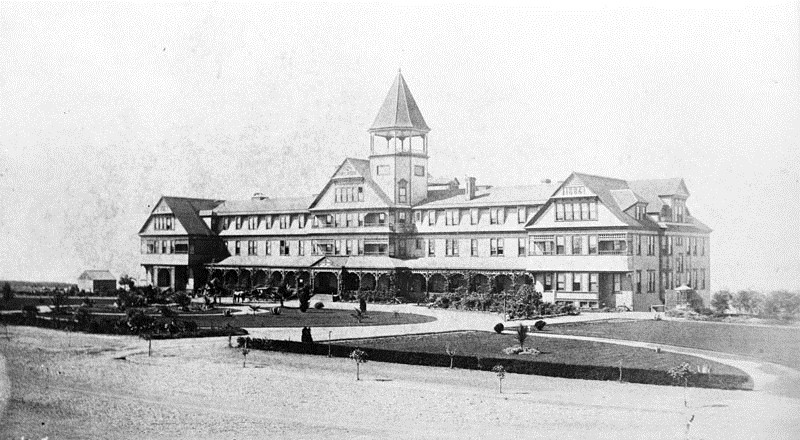

| (1887)* - Exterior view of the east front of the Arcadia Hotel in Santa Monica soon after opened in March 1887. It was located on Ocean Avenue immediately south of the bridge over the gulch that was later occupied by Roosevelt Highway. The hotel was built next to a steep cliff and shows only 3 stories on the Ocean Avenue side and 5 stories on the beach side. |

Historical Notes The Arcadia Hotel opened for business in 1887 and was located on Ocean Avenue between Railroad Avenue (later known as Colorado Avenue) and Front (later known as Pico Boulevard). The Arcadia was the largest structure in Santa Monica at the time of its construction. The 125-room hotel was owned by J.W. Scott, the proprietor of the city's first hotel, the Santa Monica Hotel. The hotel was named for Arcadia Bandini de Baker, the wife of Santa Monica cofounder Colonel R. S. Baker. |

|

|

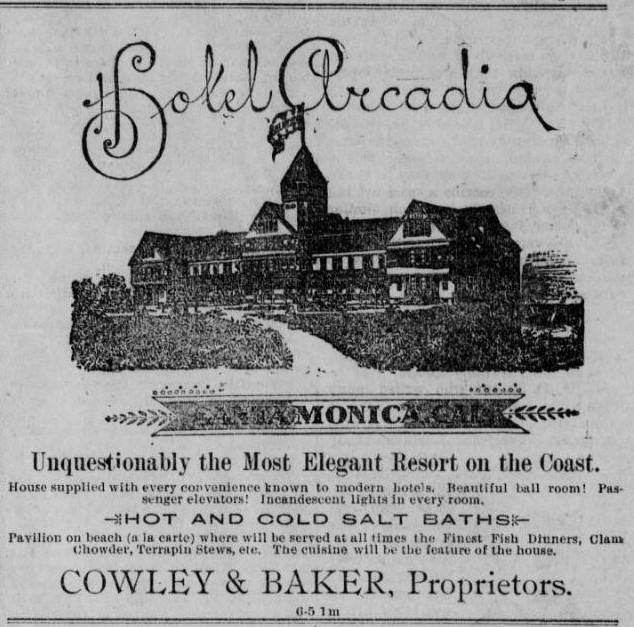

| (1890)**^ - Hotel Arcadia - 'The Most Elegant Resort on the Coast....with Passenger Elevators!' |

Historical Notes Being located on a bluff, all 125 rooms in the 5-story building boasted unobstructed views. It featured a grand ballroom, upscale dining room and its own roller coaster. A bathhouse was located on the beach directly below the hotel, offering guests hot saltwater baths. The pinnacle of the hotel was an observation tower, offering breathtaking views in every direction a dizzying 136 feet above the beach level. |

|

|

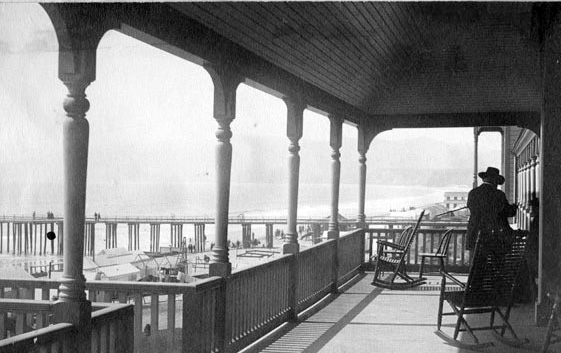

| (ca. 1890)* - View looking north from the veranda of the Arcadia Hotel showing pier and Santa Monica shoreline. |

|

|

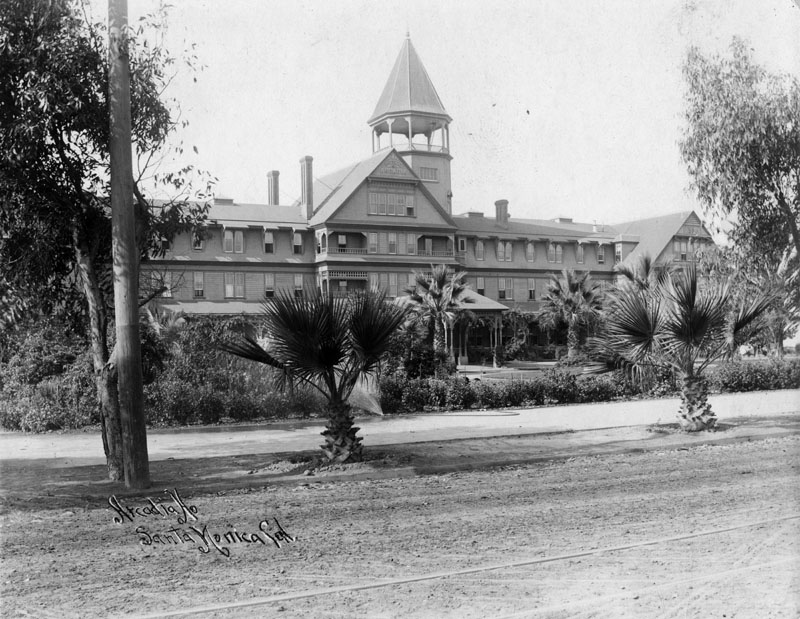

| (1890)* - Arcadia Hotel from the street side. The hotel was named for Arcadia Bandini de Baker, the wife of Santa Monica cofounder Colonel R. S. Baker. |

Historical Notes The Arcadia Hotel was the site where Colonel Griffith J. Griffith shot his wife in 1903, which led to their divorce and his (short) imprisonment. In 1882 Griffith moved to Los Angeles and purchased approximately 4,000 acres of the Rancho Los Feliz Mexican land grant. On December 16, 1896, Griffith and his wife Christina presented 3,015 acres of the Rancho Los Feliz to the city of Los Angeles for use as a public park. Griffith called it "a Christmas present." After accepting the donation, the city passed an ordinance to name the property Griffith Park, in honor of the donor. Griffith later donated another 1,000 acres along the Los Angeles River. |

|

|

| (1890s)* - View of the Arcadia Hotel from the street. The landscaping is now more fully developed. |

Historical Notes The Arcadia Hotel was a landmark, hailed as one of the finest hotels in Southern California in its day. However, like many hotels in the area, the Arcadia hotel was forced to close in times of slow business; the hotel closed for one year from 1888-1889, and permanently in 1906 when the building boom subsided. In 1907, there was a failed attempt to convert the hotel into a private school for the California Military Academy, but the property stood abandoned until it was demolished in 1909 to make room for beach improvements, homes, and hotels. |

|

|

| (1890s)* - Panoramic view of the Arcadia Hotel looking towards the ocean. In front of the hotel are extensive, well manicured lawns and gardens. |

|

|

| (1887)* – View looking North from top of the newly-built Arcadia Hotel showing the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Santa Monica station. The coastline and Palisades are seen on the left. |

|

|

| (1888)* - View showing the Thompson Gravity Switchback Railroad (aka Switchback Roller Coaster) on the left, which traveled across the ravine between the Arcadia Hotel (not pictured) and the north side of the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks. The Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Santa Monica Depot is on the right. |

* * * * * |

Thompson Gravity Switchback Railroad (aka Switchback Roller Coaster)

|

|

| (ca. 1887)*^* - The 'Switchback Roller Coaster' with the Arcadia Hotel in the background. |

Historical Notes A special delight for Arcadia Hotel guests was a two-track gravity switchback roller coaster, which in a one minute journey, could whisk guests either to or from the hotel and back again. For five cents, riders would climb a platform to board the large bench-like car and were pushed off to coast 300 ft. down the track across the ravine. The car went just over 6 mph. At the top of the other platform the vehicle was switched to a return track or "switched back" (hence the name). |

|

|

| (1880s)* - View of the switchback roller coaster in motion halfway between the Arcadia Hotel and its end point on the Santa Monica bluffs. |

Historical Notes The original Switchback Railway (Coney Island) was the first roller coaster designed as an amusement ride in America. It was designed by LaMarcus Adna Thompson in 1881 and constructed in 1884. It appears Thompson based his design, at least in part, on the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway which was a coal-mining train that had started carrying passengers as a thrill ride in 1827. |

|

|

| (ca. 1887)#^^ - View showing several men and women in a roller coaster as it comes to the end of its ride across the Santa Monica bluffs. In the background is seen the Arcadia Hotel with a flag flying high from the top of its observation tower. |

|

|

| (1894)* - Bird’s eye view looking north from the Arcadia Hotel showing the bridge over the gulch that was later occupied by the Roosevelt Highway. Note that the Switchback Roller Coaster is no longer there. Click HERE to see same view in 1888. |

|

|

| (1894)* – View looking northeast from the Arcadia Hotel showing hotel on corner, horse-drawn trolley in street (left), Santa Monica railroad station with train (distant left), Santa Monica Stables (center right), and landscaped parkway (center foreground). |

|

|

| (ca. 1890s)* - Railroad Avenue (now Colorado). The Arcadia Hotel is seen in the background. The famed beachfront establishment was on Ocean Avenue between Railroad Avenue and Front Street (now Pico Boulevard). |

|

|

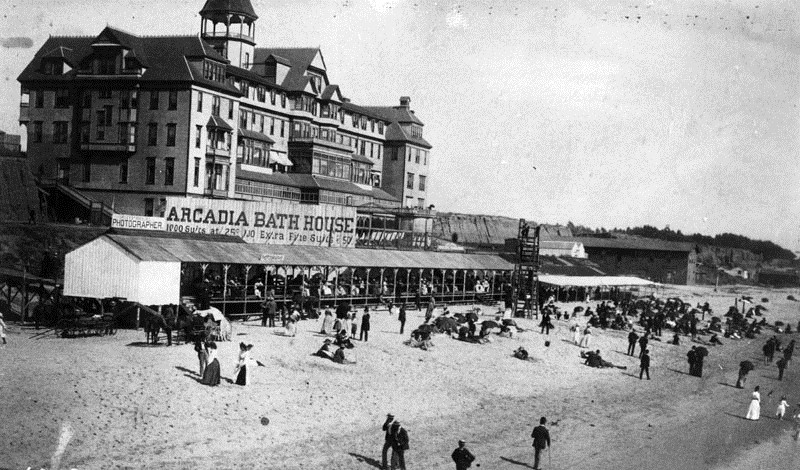

| (ca. 1898)^ - Postcard view showing the beach side of the Arcadia Hotel and bath house as seen from the 1898-built North Beach Bath House Pier. The portion of a pier at left is the remains of the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Wharf. |

Historical Notes The Arcadia Hotel opened for business in 1887 and was located on Ocean Avenue between Railroad Avenue (later known as Colorado Avenue) and Front (later known as Pico Boulevard). The Arcadia was the largest structure in Santa Monica at the time of its construction. The 125-room hotel was owned by J.W. Scott, the proprietor of the city's first hotel, the Santa Monica Hotel. The hotel was named for Arcadia Bandini de Baker, the wife of Santa Monica cofounder Colonel R. S. Baker. The hotel was built next to a steep cliff and shows only 3 stories on the Ocean Avenue side and 5 stories on the beach side as seen above. |

|

|

| (ca. 1898)* - Postcard view showing the beach side of the Arcadia Hotel and bath house as seen from the 1898-built North Beach Bath House Pier. The portion of a pier at left is the remains of the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Wharf. Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

|

|

| (1890s)* - Slightly different view of the Arcadia Hotel with the remains of the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Wharf on the left. |

|

|

| (ca. 1898)* - Image of the North Beach Bath House and Arcadia Bath Houses on the beach with people lying in the sand and piers visible in the distance. Signs are visible that read "Anheuser Busch beer St. Louis Eckert & Hopf" and "Arcadia Bathhouse." The portion of the pier at center is the remains of the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad Wharf. |

Historical Notes The North Beach Bath House was built in 1898 and replaced the 1876-built Santa Monica Bath House. |

|

|

| (ca. 1898)* - View looking south from the North Beach Bath House showing the beach and pier (remaining portion of the Los Angeles and Independence Pier) near the Arcadia Hotel and Arcadia Bath House. Visible signs include "Arcadia Bath House, 500 new suits, new tubs, fish grill room" and "Casa Colorado" (partially painted over Anheuser Busch lettering). People are seen walking along a wooden boardwalk, including women with parasols, horse-drawn wagons, a carousel tent, and various small boats on the sand are also visible. A windmill can be seen in the distance. |

|

|

| (ca. 1898)* - Looking south from the North Beach Bath House showing the beach and pier (remaining portion of the Los Angeles and Independence Pier) near the Arcadia Hotel and Arcadia Bath House. Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - Another view from the pier showing the Arcadia Hotel on Santa Monica South Beach behind the Arcadia Bath House. |

Historical Notes When it opened in 1887, Santa Monica's ritzy Arcadia Hotel offered its guests a large saltwater bathhouse, the Arcadia Bath House. |

|

|

| (1890)* - A closer view of South Beach. People are walking and sitting in front of the Arcadia Bath House with the Arcadia Hotel sitting in the background. |

|

|

| (ca. 1892)* - Photograph of the Arcadia Hotel and Bath House in Santa Monica, ca.1892-1898. The beach is at low tide and to the far right, the ocean can be seen crashing against the shore. Groups of people play or walk in the surf while others sunbathe on the sandy beach. To the far left, sits the large four-story wooden Arcadia Hotel with a turret on its roof. Along the base of the hotel, a tented pavilion is visible on the beach. Legible signs include: "Arcadia Bath House" and "Clam Chowder” |

|

|

| (1890)* - People walking on the Santa Monica Beach boardwalk. A horse-drawn carriage (center of photo) appears to be heading south along the sand, parallel to the boardwalk. |

|

|

| (ca. 1895)* - View of South Beach looking north toward the Arcadia Hotel and Palisades. The long boardwalk can be seen extending all the way to the hotel. |

|

|

| (1888)* - Bathhouses on the beach near Santa Monica with the Arcadia Hotel standing in the background. The pier can also be seen. |

* * * * * |

Southern Pacific Railroad Tunnel

|

|

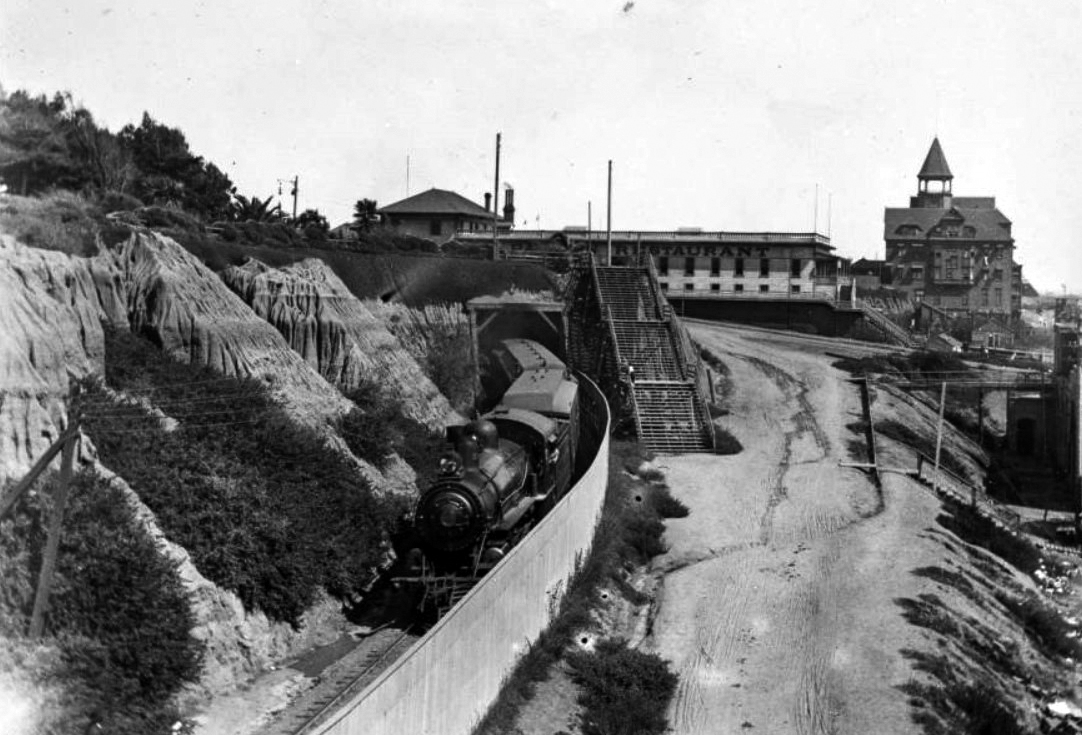

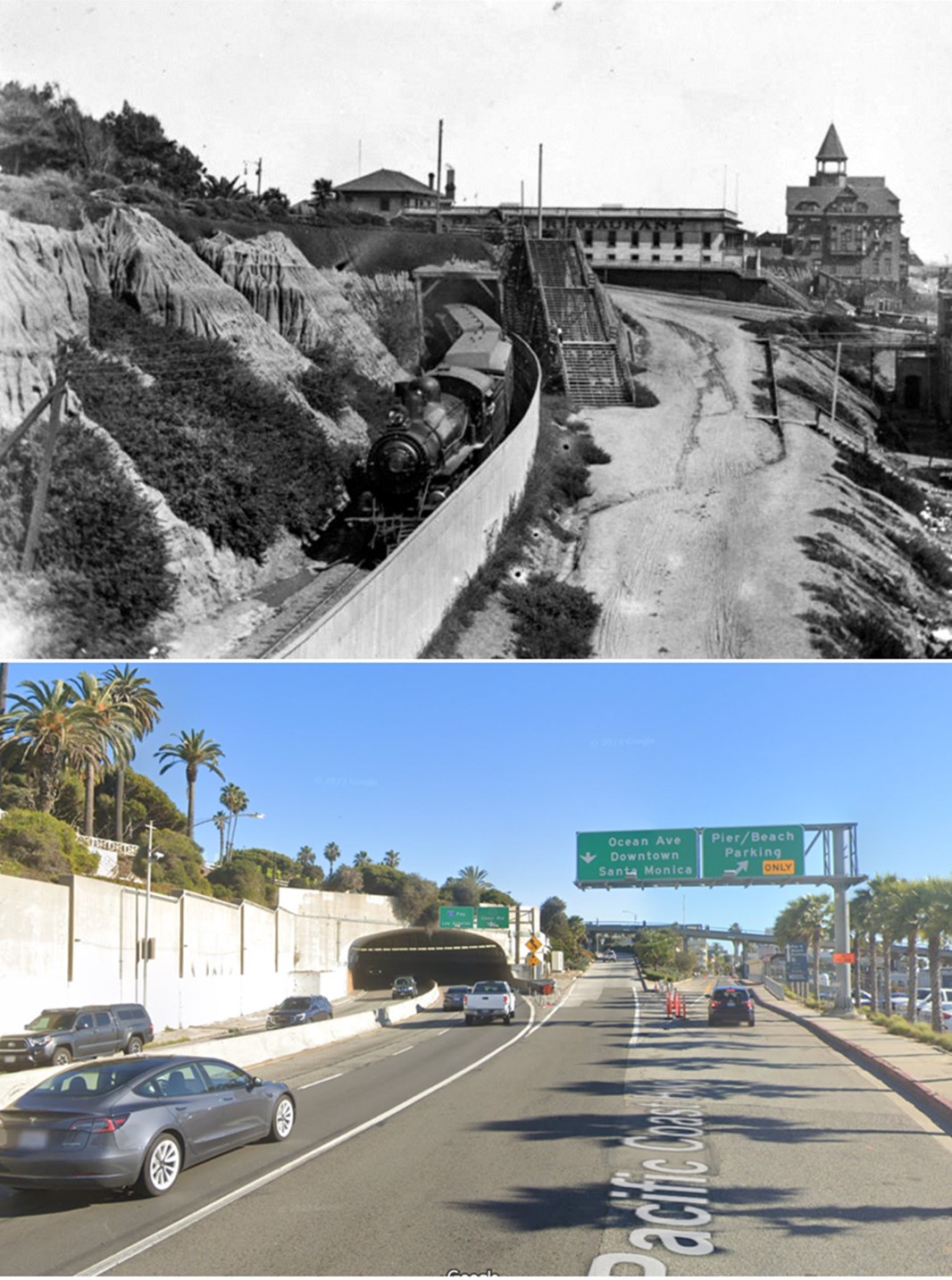

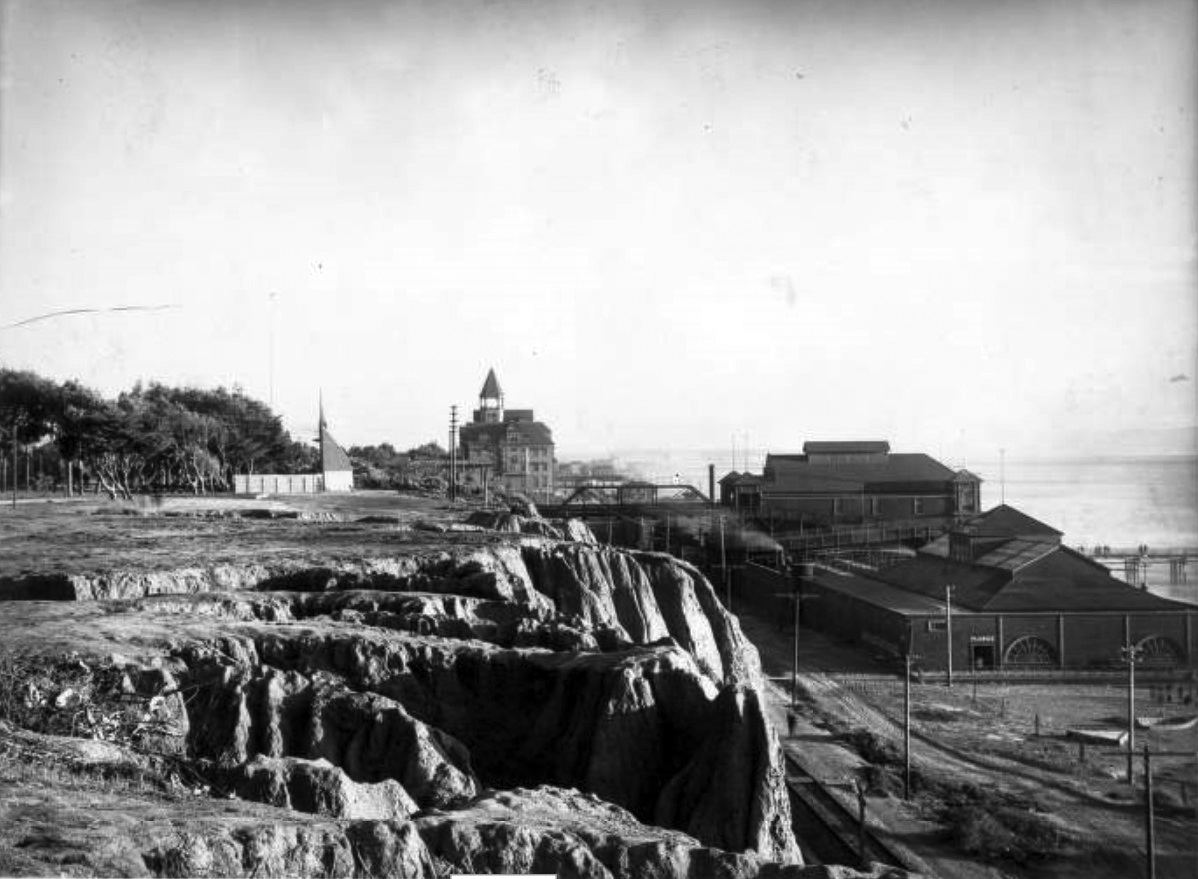

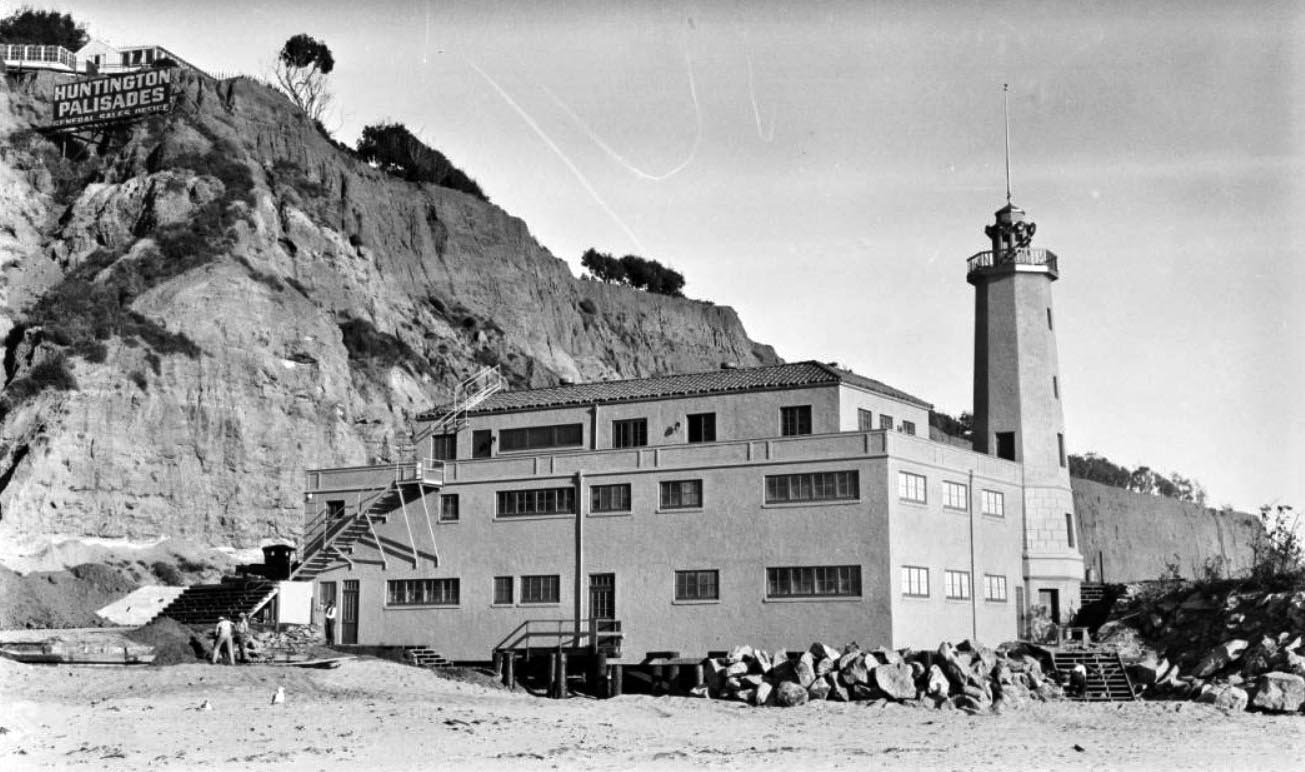

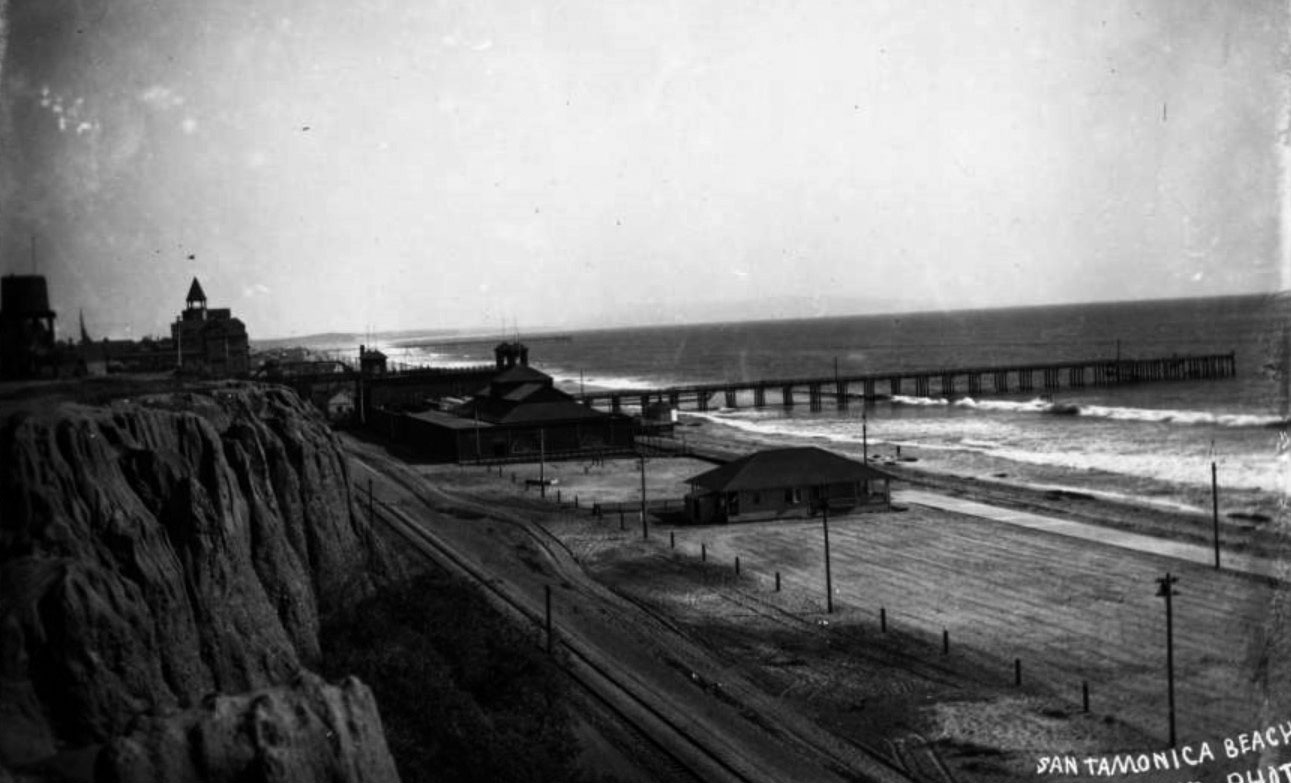

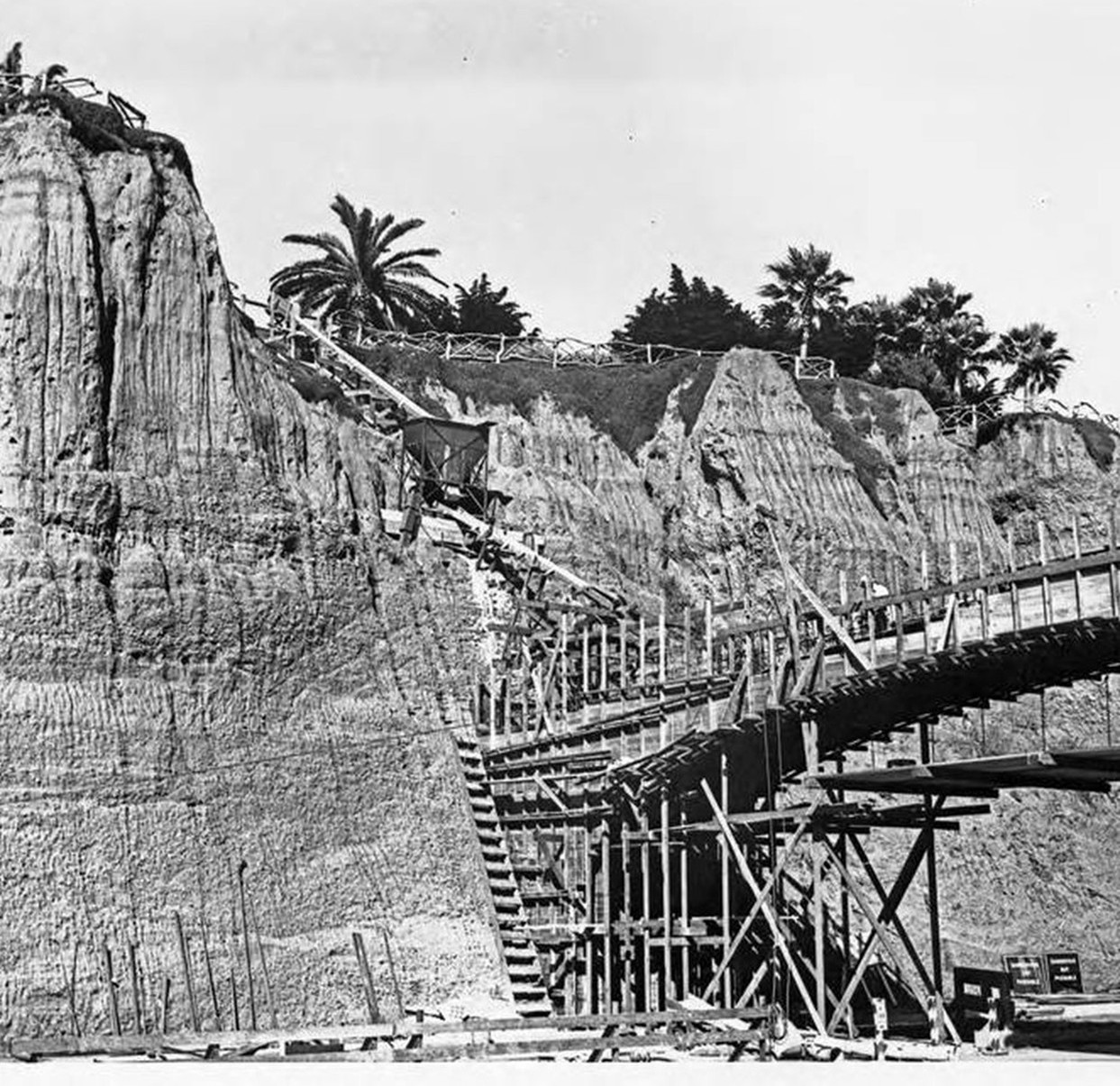

| (1890s)* - View looking south of the Arcadia Hotel and the Arcadia Bath House. The Southern Pacific Railroad tunnel is seen at center. At right are the '55 steps' that enabled visitors to have quick access to the beach below. |

Historical Notes In 1891, the Southern Pacific Railroad built a tunnel under Ocean Avenue for its new rail line to Santa Monica Canyon that was later sold to the Pacific Electric Railway . The rail line was in use from 1891 to 1933. |

|

|

| (1896)^ – View showing a Southern Pacific train emerging from a tunnel, with the Arcadia Hotel in the distance on the right. |

Historical Notes In 1936, the Southern Pacific Tunnel was enlarged for vehicular use (later renamed McClure Tunnel) and connected Lincoln Boulevard with the Roosevelt Highway (later PCH). Click HERE to see more. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1896 vs. 2023)* - Southern Pacific Railroad Tunnel, today the McClure Tunnel. |

* * * * * |

Arcadia Hotel

|

|

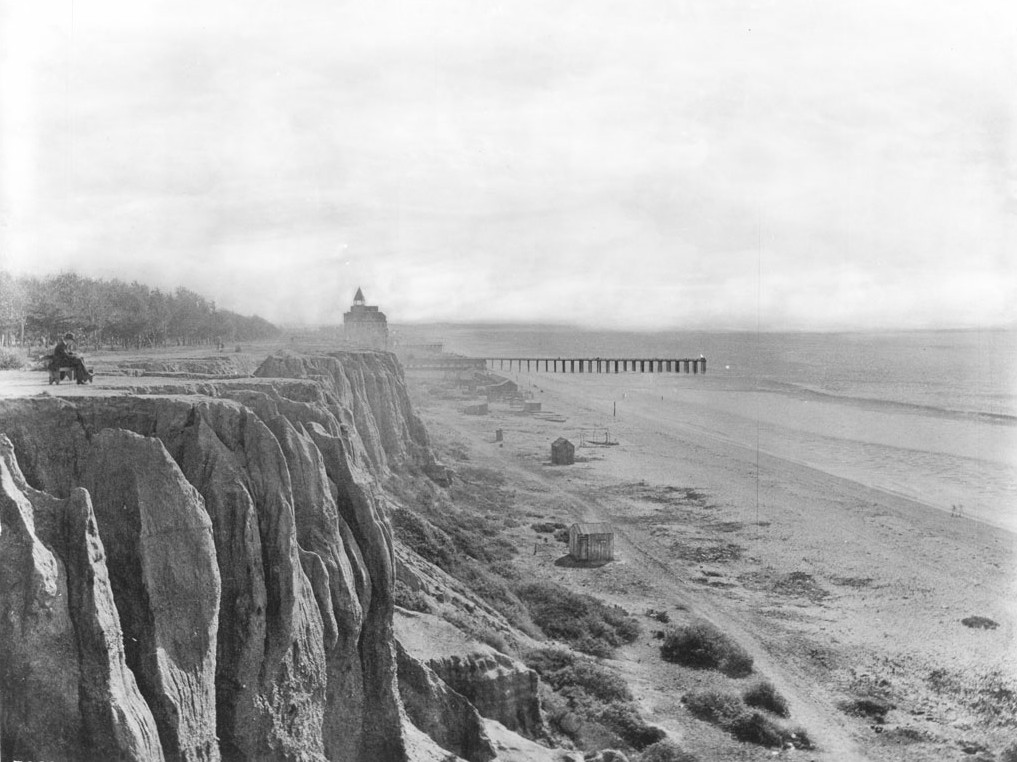

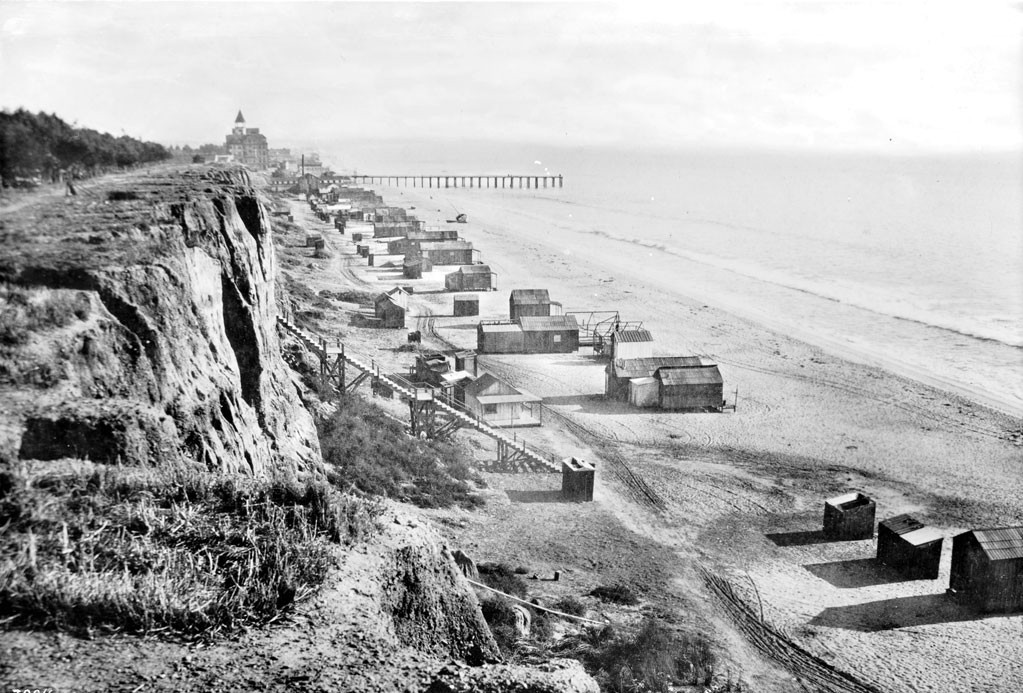

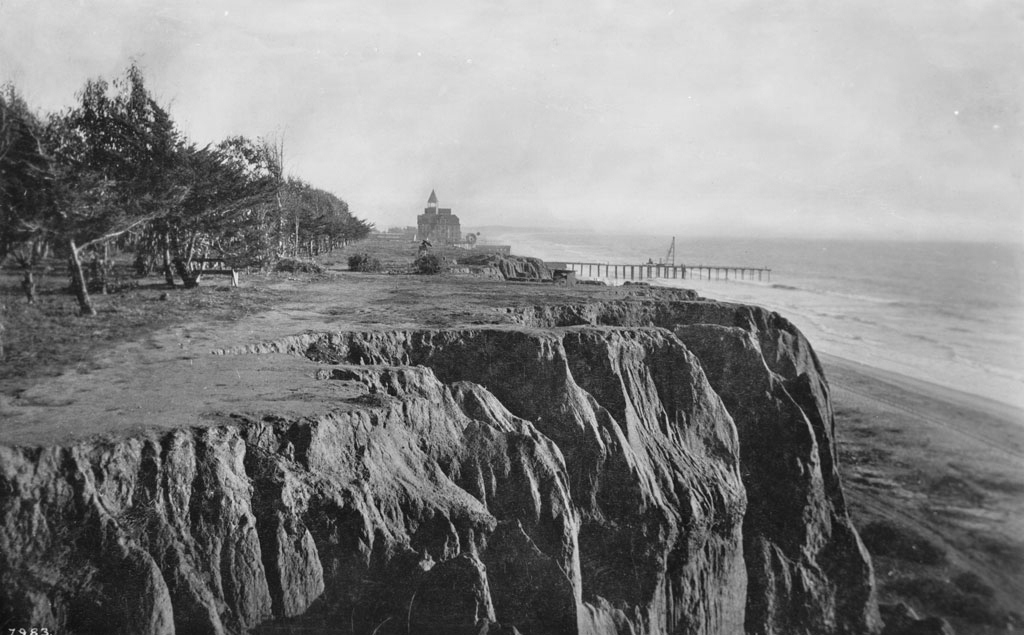

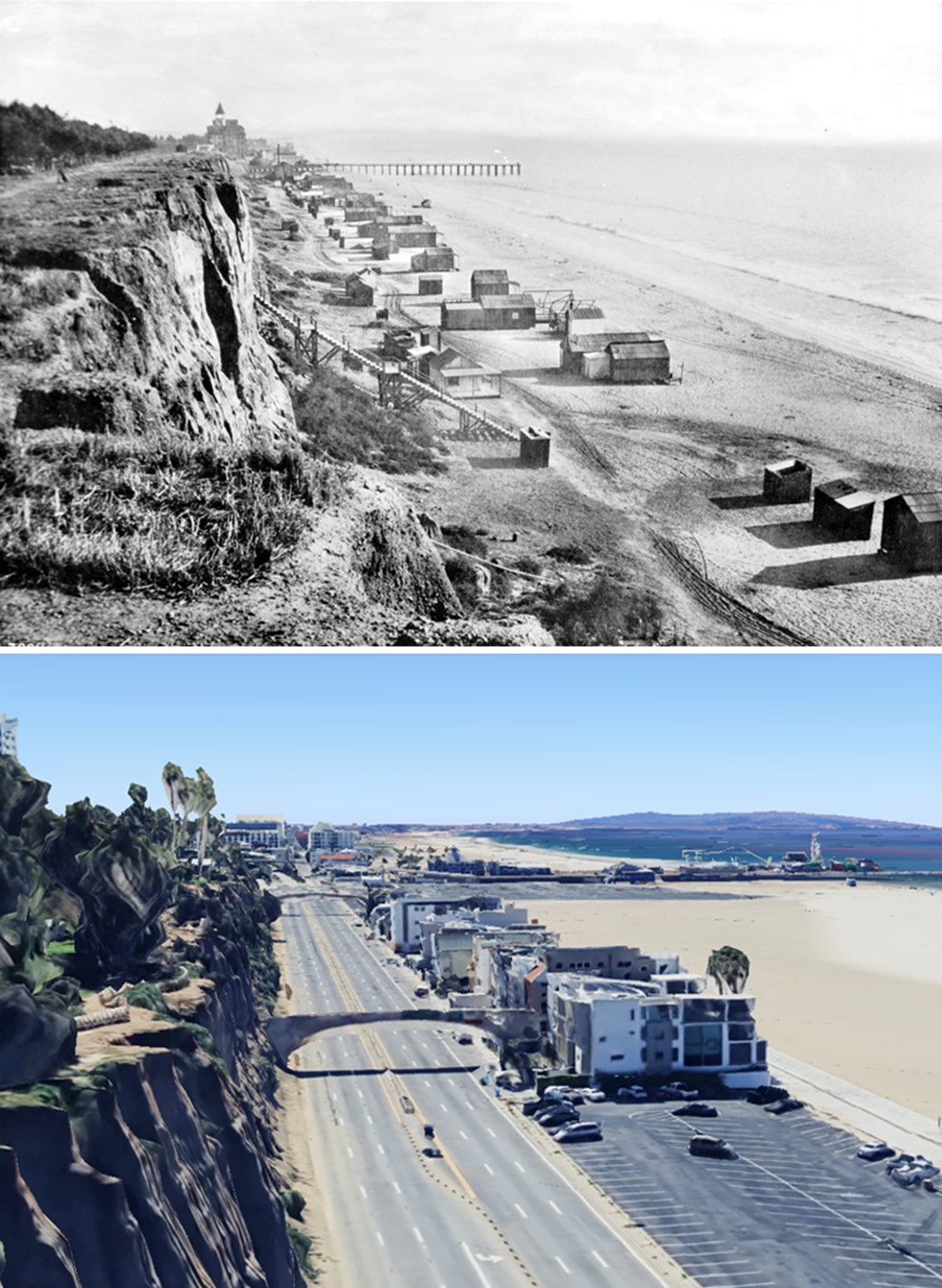

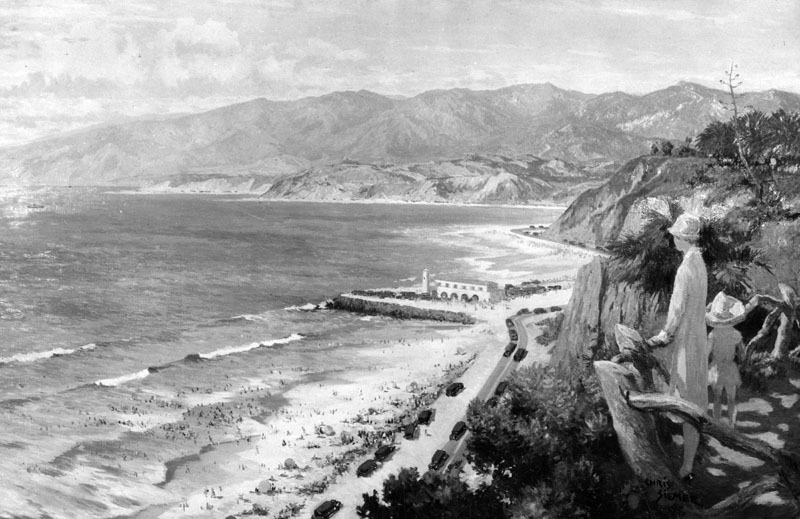

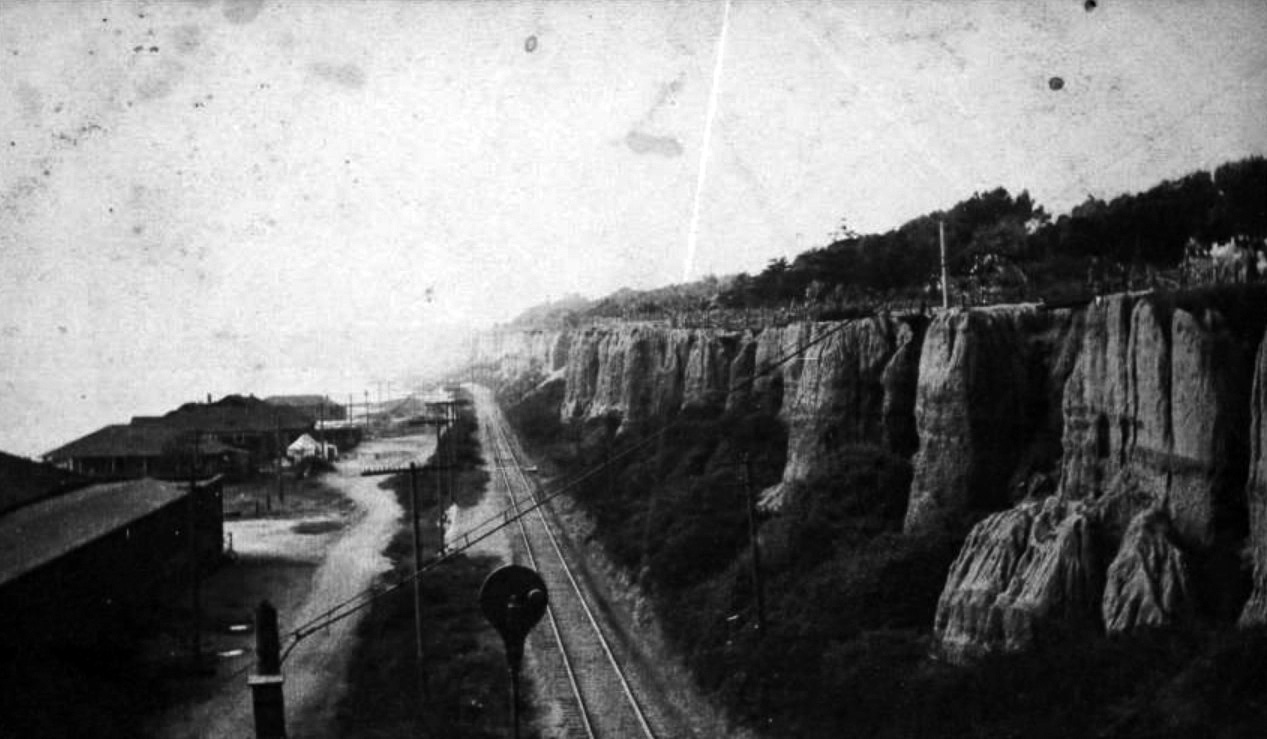

| (1904)^ – View showing the alluvial bluffs of Linda Vista Park (renamed Palisades Park in the 1920s) with the Arcadia Hotel in the distance at center and the North Beach Bath House at right. Train tracks are visible below the cliffs, behind the bathhouse and the North Beach Pier (built in 1898) is seen at far right. |

Historical Notes The Arcadia Hotel was built in 1887 and demolished in 1907. |

|

|

| (1904)^ – View showing the alluvial bluffs of Linda Vista Park (renamed Palisades Park in the 1920s) with the Arcadia Hotel in the distance at center and the North Beach Bath House at right. (AI image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff) |

|

|

| (ca. 1905)* - Spectators stand on a partially destroyed boardwalk looking at the damage in the aftermath of a storm. A man on horseback is seen on the beach and the Arcadia Hotel stands in the background. |

|

|

| (ca. 1905)* - Spectators stand on a partially destroyed boardwalk looking at the damage in the aftermath of a storm. A man on horseback is seen on the beach and the Arcadia Hotel stands in the background. |

* * * * * |

Santa Monica Bathing

|

|

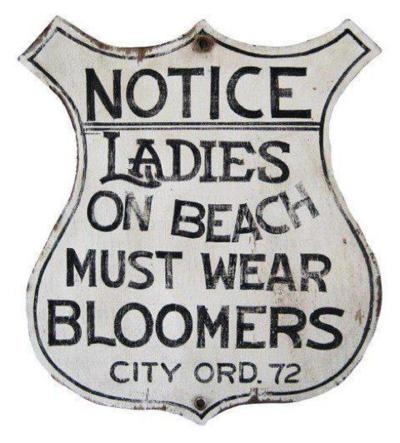

| (1910s)* - Neighboring Venice Beach sign. (Truth or Fiction?) |

Historical Notes The sign reading “NOTICE: LADIES ON BEACH MUST WEAR BLOOMERS – CITY ORD. 72” appears to be a novelty reproduction rather than an authentic municipal posting from Venice Beach or nearby coastal towns. However, its message draws from real history. In the early 1900s, many seaside communities in Southern California, including Venice, enforced strict modesty laws that dictated what women could wear at the beach. Bloomers and full-length bathing attire were often required, and so-called “swimsuit police” or “beach censors” patrolled the sand, sometimes measuring women’s suits to ensure compliance. Famous photographs from the 1920s and 1930s show officers at Venice Beach inspecting beachgoers’ attire—evidence of genuine social norms that inspired signs like this, whether in jest or homage. While no known city ordinance matches “ORD. 72,” the sign captures, through exaggeration or satire, the era’s tension between public decency codes and evolving fashion freedoms. |

|

|

| (1890)* - Group photo of men and women in their bathing suits, standing in ankle deep water on Santa Monica beach. |

Historical Notes In the 1890s, Santa Monica Beach was a burgeoning seaside resort, attracting visitors eager to enjoy the Pacific surf and the burgeoning amenities of the area. Group photographs from this era often depict bathers in modest swimwear, reflective of the Victorian and Edwardian sensibilities of the time. These group photos were more than mere snapshots; they served as cherished mementos of seaside excursions. Photographers would set up along the beach, offering visitors the opportunity to capture their leisure moments, which were then printed as souvenir postcards or keepsakes. Such images not only documented personal memories but also contributed to the broader cultural narrative of beach-going as a fashionable and wholesome activity during that period. |

|

|

| (1890s)* - View showing a group of men, women and children wearing bathing suits and caps and holding seaweed while standing in an incoming wave on the beach in Santa Monica, with a pier at right. |

Historical Notes Women's bathing attire typically consisted of dark-colored, knee-length dresses with puffed sleeves, worn over bloomers or stockings, and complemented by bathing caps or wide-brimmed hats to shield from the sun. Men's swimwear was usually one-piece woolen suits that covered the torso and extended to the mid-thigh, often in darker hues. |

* * * * * |

|

|

| (1890)* - People in front of their house-tents near the Santa Monica beach. |

|

|

| (1890)* - View of an unpaved Ocean Avenue showing large residences and many trees lining the sidewalk. |

* * * * * |

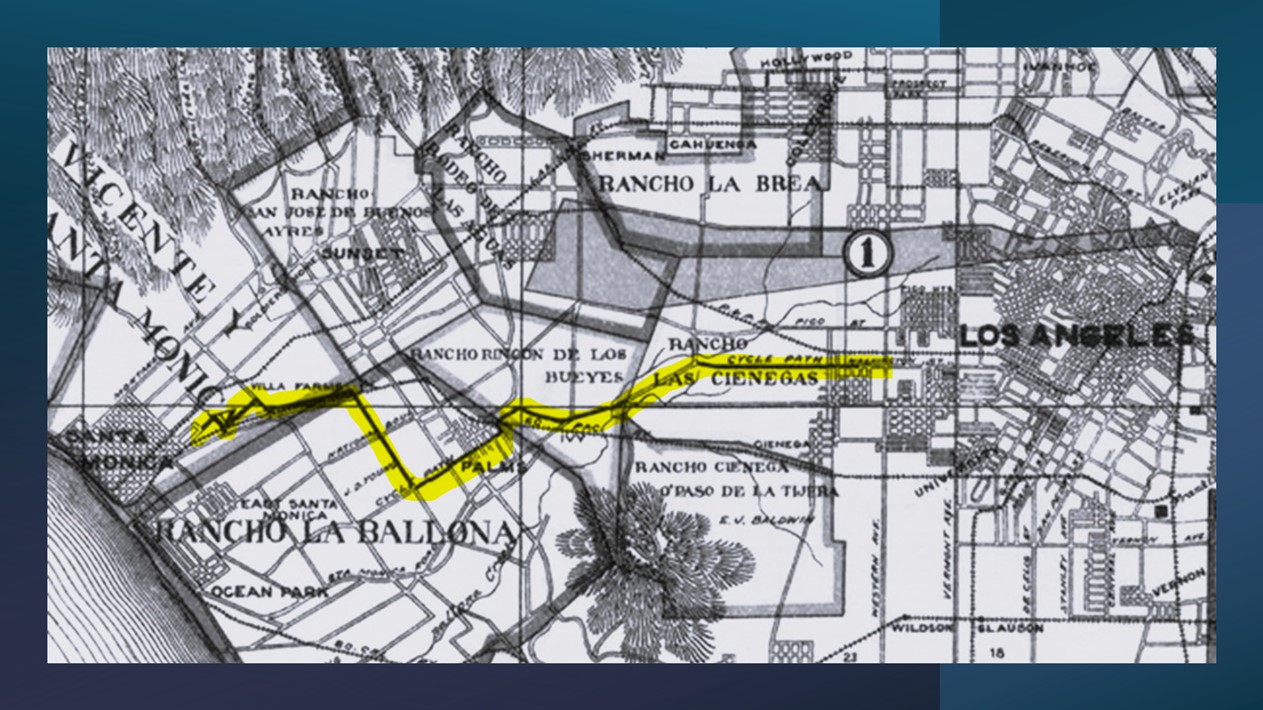

Santa Monica Cycle Path

|

|

| (1896)* - The beginning of the Santa Monica Bicycle Path on Washington Street (later Boulevard) and Third Avenue in Los Angeles. The view is looking west. A bicycle is leaned against a trellis that reads "Cycle Path" across its top. A horse and buggy can be seen making their way along Washington. The photo by C.C. Pierce is dated 1896, although the entire Santa Monica Bike Path wasn't completed until 1900, according to various sources. |

| Historical Notes

The Santa Monica Cycle Path was a pioneering bicycle route in Los Angeles, completed in 1900. It was an 18 mile cycleway that provided a smooth and reliable route from downtown Los Angeles to the coast at Santa Monica. At a time when most roads were rough and poorly maintained, the path offered cyclists a safer and more efficient alternative. The cycle path was a six foot wide gravel road reserved for cyclists and pedestrians. Decorative arches marked the route and prevented wagons and buggies from entering. These arches also displayed advertisements that helped fund construction and maintenance of the path. Along the route, riders passed through open farmland, meadows, and developing industrial areas, including the Hauser slaughterhouse. Newly planted pepper trees provided shade and made the ride more comfortable. When the path opened, it greatly reduced travel time between Los Angeles and Santa Monica. It quickly became popular with cyclists who no longer had to rely on difficult wagon roads. Location note |

|

|

| (1900)* - The Santa Monica Cycle Path is highlighted in this 1900 map of Los Angeles County by A.L. George. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

| Historical Notes

The 18 mile Santa Monica Cycle Path was a dedicated bicycle route that connected downtown Los Angeles with the coastal city of Santa Monica. Beginning near the city center, the path followed Washington Street, later renamed Washington Boulevard, creating a direct east west route across the city. Key intersections along the way included Third Avenue and Western Avenue. West of these points, the path passed through less developed areas, including what is now Culver City, before reaching Santa Monica and its coastal attractions. Washington Street was renamed Washington Boulevard in the early 1900s as the roadway was widened and improved. By 1905, it was already commonly referred to as Washington Boulevard and was used for organized horse driving events west of Western Avenue. |

|

|

| (1900)* - Photograph of the Santa Monica Cycle Path on Washington Street (by 1905, Boulevard) and Western Avenue, looking west, Los Angeles. A bicycle stands upright in the middle of the unpaved path, while a rider on his bicycle can be seen in the distance, pedaling along a row of telephone poles. |

| Historical Notes

The Santa Monica Cycle Path was built as part of the good roads movement led by the League of American Wheelmen. The movement focused on improving road conditions, first for cyclists and later for all travelers. Fundraising for the path also served as publicity, with supporters purchasing good roads buttons instead of paying a toll. The path crossed Washington Boulevard at Western Avenue, an important point along the route between Los Angeles and Santa Monica. |

|

|

| (2022)* - Looking west on Washington Boulevard at Western Avenue, showing the location where the Santa Monica Cycle Path once existed. |

| Historical Notes

Despite its early success, the rise of the automobile in the early 20th century led to the decline of dedicated bicycle paths like this one. The Santa Monica Cycle Path eventually fell into disuse as streets were redesigned to serve cars. Even so, it remains an important chapter in Los Angeles transportation history and an early example of dedicated infrastructure for cyclists. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1900 vs 2022)* - Looking west on Washington Boulevard at Western Avenue, showing the location of the Santa Monica Cycle Path. |

| Historical Notes

The Santa Monica Cycle Path, along with the California Cycleway in Pasadena, reflected the cycling boom of the 1890s, when Los Angeles had more than 35,000 cyclists. These projects were early attempts to create dedicated infrastructure for non motorized travel, long before automobiles shaped the region. Although neither project lasted for many years, both remain important chapters in the history of transportation and urban planning in Southern California. |

* * * * * |

Senator Jones Residence (Miramar Hotel)

|

|

| (ca. 1890s)* - View of Miramar, the home of Senator John P. Jones and Georgina Frances Sullivan Jones, built in 1889 and located Ocean Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard. Photo is inscribed with an arrow, "Room where Gregory Jones was born 1894." |

Historical Notes Senator Jones built a mansion, Miramar, and his wife Georgina planted a Moreton Bay Fig tree in its front yard in 1889. The tree is now in the courtyard of the Fairmont Miramar Hotel and is the second-largest such tree in California, the largest being the tree in Santa Barbara. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890s)* - View of Miramar, the home of Senator John P. Jones and Georgina Frances Sullivan Jones, built in 1889 and located Ocean Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard. Photo is inscribed with an arrow, "Room where Gregory Jones was born 1894." Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - View of Senator Jones residence (later the site of the Miramar Hotel) in Santa Monica showing front lawn across drive. A footpath leads from the drive to the house and is crossed by another path which goes around the house. The house itself has two round turrets in front. |

|

|

| (ca. 1890)* - Closer view of Senator John P. Jones' residence on Ocean Avenue. |

|

|

| (1895)* - Residence of Senator John P. Jones called Miramar on Ocean Avenue. |

| Historical Notes

In 1924 Senator Jones’ mansion became the grand Miramar Hotel |

|

|

| (1937)* - Exterior view of the entrance to the Miramar Hotel in Santa Monica, located on the northeast corner of Ocean Park and Wilshire Blvds. It is one of Santa Monica's oldest landmarks, dating back to 1888. |

| Historical Notes

Originally the location of Santa Monica's founding father Senator Jones mansion, the Miramar has provided shelter for rich and famous guests looking for an extended beach stay since the 1920s. Notables include Cary Grant, John F Kennedy, Charles Lindbergh and Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1924 the six-story Palisades Wing was constructed to provide apartments for guests who planned lengthy stays at the beach. Scandinavian beauty Greta Garbo was one of the first celebrity guests to move into the wing and resided there for more than four years. Sultry blonde Jean Harlow rented one of the Miramar's bungalows in the early 1930s, and years later another famous blonde, Marilyn Monroe, frequently retreated to the Miramar when she wanted to disappear from the media. |

* * * * * |

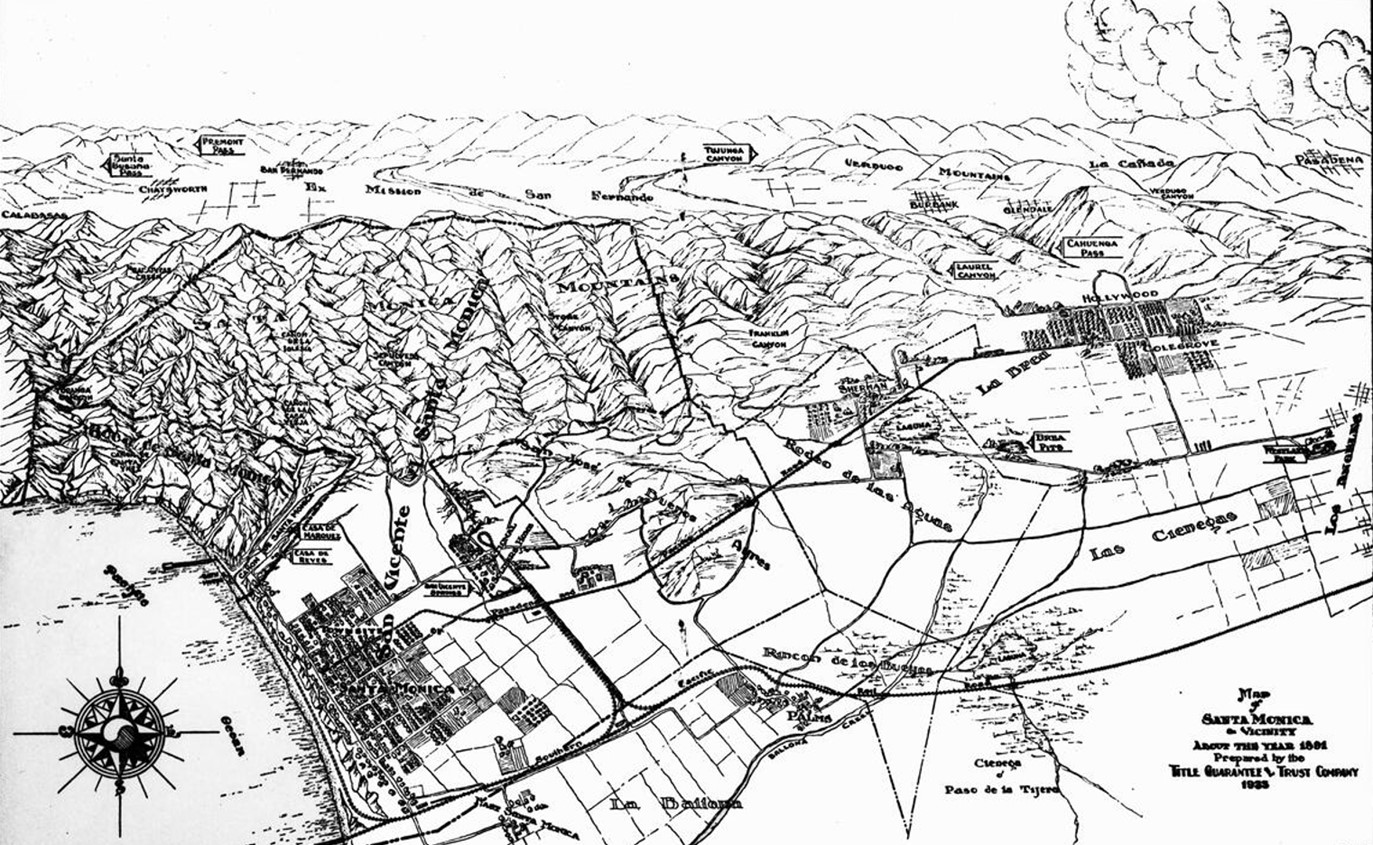

Santa Monica Map

|

|

| (1891)*– Photo of a map of Santa Monica and vicinity as it appeared in 1891. Santa Monica can be seen in the lower left corner, near a small part of the Pacific Ocean. Mountains are visible above Santa Monica, and the city of Los Angeles can be seen in the lower right corner. |

| Historical Notes

The above map was prepared by the Title Guarantee & Trust Company in 1935. Other landmarks on the map include, from left to right, top to bottom: Calabasas, Santa Susana Pass, Chatsworth, Fremont Pass, San Bernardo, El Mission de San Fernando, Tujunga Canyon, Verdugo Mountains, Burbank, Glendale, Laurel Canyon, Cahuenga Pass, La Canada, Verdugo Canyon, Pasadena, Santa Monica Mountains, Sepulveda Canyon, Franklin Canyon, Sherman, Laguna, La Brea, Brea Pits, Hollywood, Colegrove, Bath House, Canon de Santa Monica, Casa de Reyes, Casa de Marquez, Rodeo de las Aguas, Las Cienegas, Westlake Park, Los Angeles, Santa Monica, Rincon de los Bueyos, and La Ballona. |

|

|

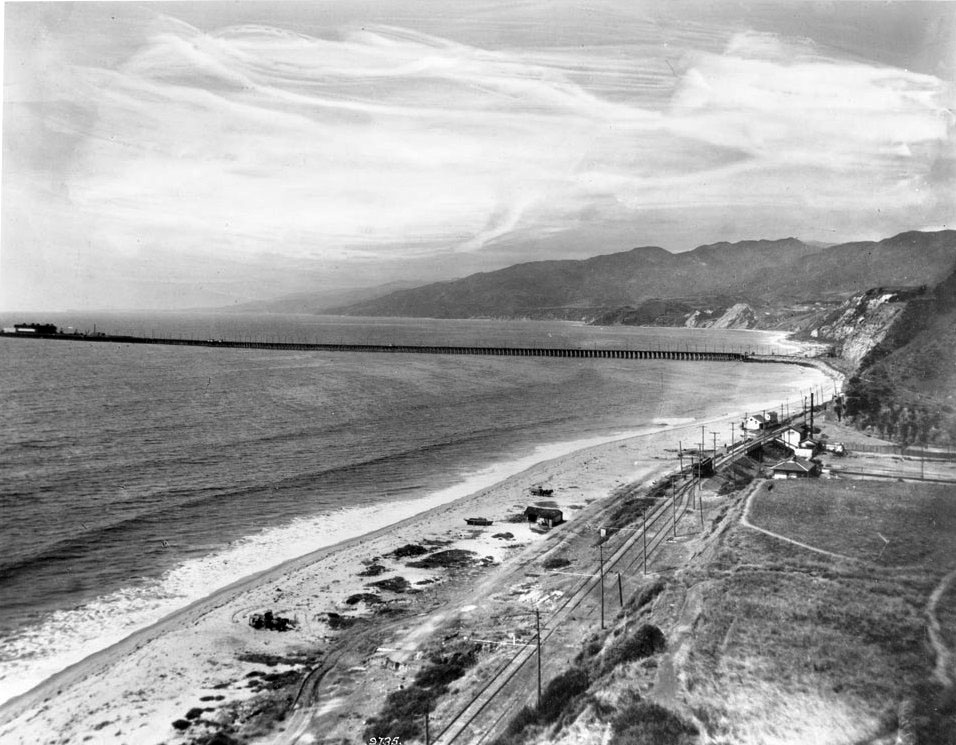

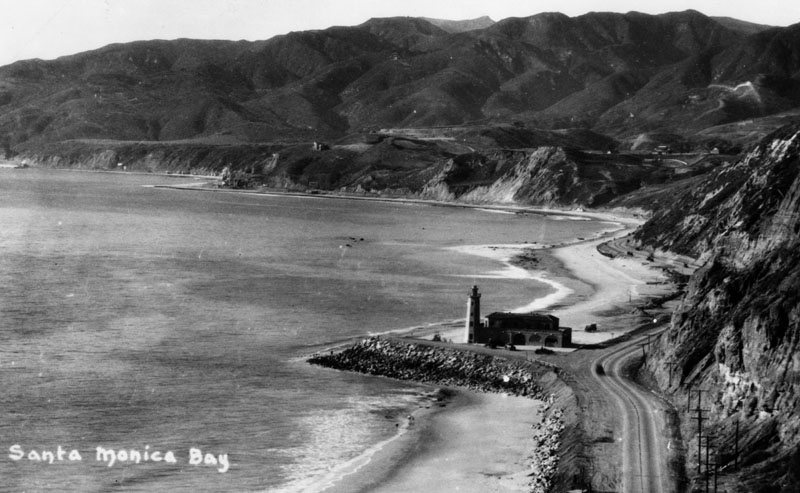

| (1890s)* - View of Palisades Park in Santa Monica, looking north from present Santa Monica Blvd. On the left is the Santa Monica beach, and the Santa Monica mountains can be seen in the background. The Long Wharf can be seen in the distance. |

* * * * * |

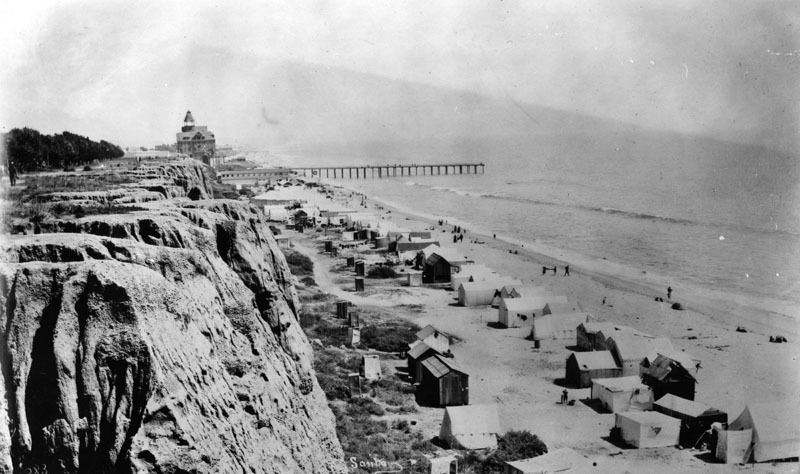

Santa Monica Long Wharf

|

|

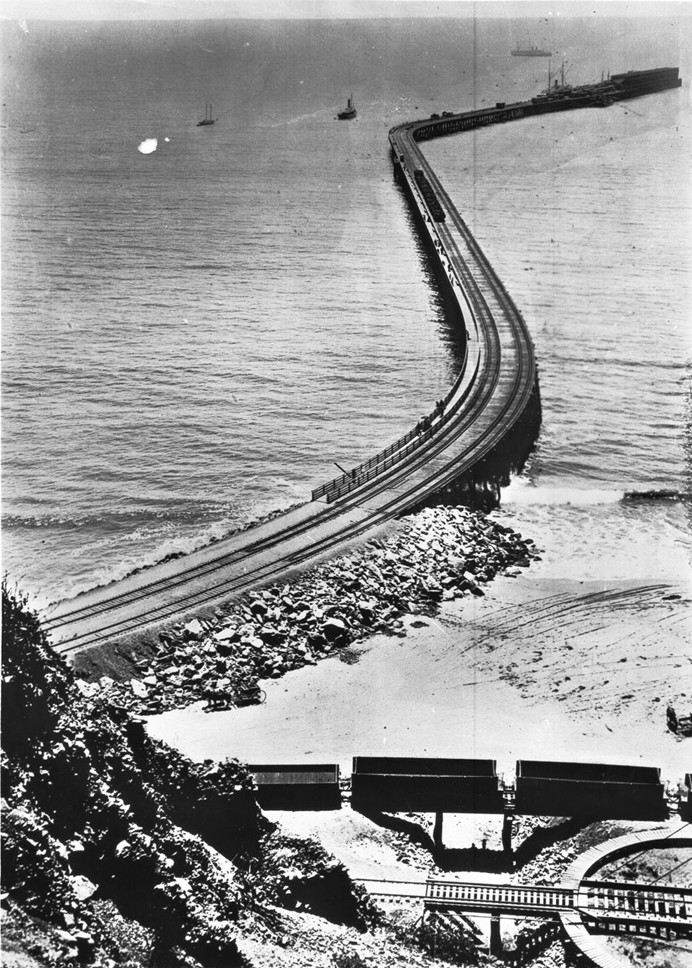

| (ca. 1893)* - The longest wharf in the world located off Pacific Palisades. A train can be seen close to the shoreline while several ships are seen near the end of the long wharf. |

Historical Notes The Long Wharf, also known as Port Los Angeles or the Mile Long Pier, was constructed between 1892 and 1894 by the Southern Pacific Railroad Company just north of Santa Monica Canyon. At nearly a mile in length, it was the longest wooden pier in the world at the time. The wharf was built to serve as a deep-water port for the Los Angeles region, addressing the area’s lack of a natural harbor and facilitating the transfer of goods and passengers between ships and railroads. |

|

|

| (1893)* – A rare view of the Long Wharf from the beach! Surf crashes in the foreground as a tall ship waits at the end of the 4,600-foot wharf, once planned to be the official Port of Los Angeles. Built by the Southern Pacific Railroad, it stretched nearly a mile into the ocean—an ambitious vision that soon gave way to San Pedro. Photo by C. M. Young from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes The Long Wharf, also known as the Santa Monica Wharf, was constructed in 1893 by the Southern Pacific Railroad as part of an ambitious plan to establish a deep-water port for Los Angeles at Santa Monica. Stretching 4,600 feet into the Pacific Ocean, it was the longest wooden pier in the world at the time. Southern Pacific sought to control the region’s shipping access and bypass the shallow, undeveloped port at San Pedro. The wharf allowed cargo ships to dock directly offshore and transfer goods to waiting trains. However, political pressure—led by the "Free Harbor Fight" and backed by the federal government—ultimately favored San Pedro, which became the official Port of Los Angeles in 1897, rendering the Long Wharf obsolete within just a few years. |

|

|

| (ca. 1893)* - Aerial view of the Southern Pacific Mammoth Wharf, Port Los Angeles, Calif. The wharf was also known as the old Santa Monica Long Wharf, north of Canyon. A white cloud of smoke can be seen from a train travelling on the tracks to the business end, at the end of the wharf. |

Historical Notes The wharf’s construction was part of a larger vision by railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington and Nevada Senator John P. Jones, who hoped to make Santa Monica Bay the principal port of Los Angeles. With double railroad tracks running its length, the Long Wharf quickly became a bustling hub for lumber and other imports essential to Southern California’s rapid development. Its impressive size and modern facilities made it a symbol of the region’s ambitions. |

|

|

| (ca. 1892–1894)* – Surveyors planning the Long Wharf in Santa Monica. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes Pictured with surveying instruments during the early planning of the Long Wharf in Santa Monica are (left to right): Fred Strichfield, Edna Orr (later Nellie Coffman of Desert Inn fame), Mr. Donovan, and Casper Tyler. The Long Wharf—built between 1892 and 1894—was once the longest pier in the world. This rare image captures a young Edna Orr before her rise as a pioneering figure in Palm Springs hospitality. Nellie Coffman (1867–1950), née Edna Beatrice Orr, was a pioneering hotelier who helped transform Palm Springs into a premier desert resort. After moving there in 1909 for her husband’s health, she opened a modest boarding house that grew into the famed Desert Inn. Known for her high standards and charm, “The Duchess of Palm Springs” attracted celebrities, dignitaries, and investors, shaping the city’s early identity as an upscale retreat. She managed the Inn until shortly before her death in 1950, leaving a lasting legacy in the region. |

|

|

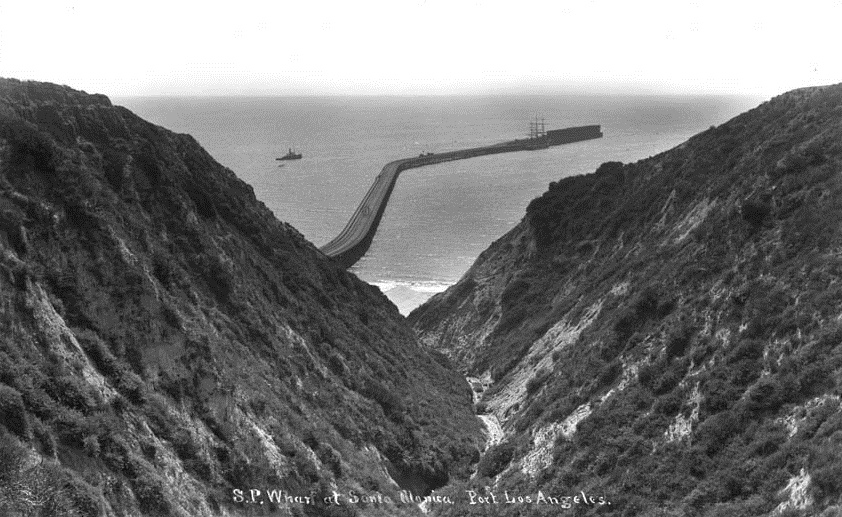

| (1895)* - View through the coastal canyon at the Long Wharf in Santa Monica, which was referred to as “Port Los Angeles” during the 1890s by the Southern Pacific Railroad. |

Historical Notes Also referred to as “Port Los Angeles” during the 1890s, the Long Wharf was promoted by the Southern Pacific Railroad as the region’s future deep-water harbor. Stretching over 4,700 feet into the bay, it was the longest pier in the world at the time. |

|

|

| (1893)* - View of the entire length of the Long Wharf from the beach all the way to its extremity almost a mile away. Note the RR turntable in the lower right corner. A horse-drawn carriage can be seen on the beach between the rail cars and the wharf. Empty railcars sit on a bridge over a gully. |

|

|

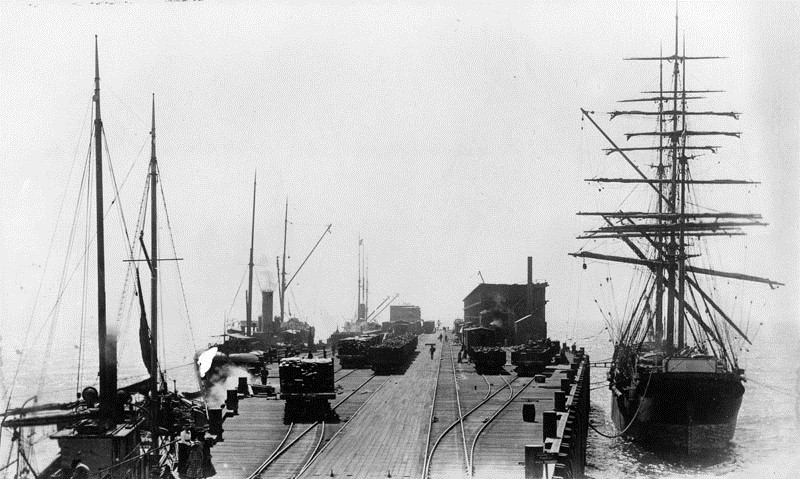

| (ca. 1890s)* - Southern Pacific Mammoth Wharf, built in 1893. Well dressed men are seen standing near a train on the 4700 foot-long wharf. |

|

|

| (1893)* - This photograph shows the arrival of the first steamer at the Southern Pacific wharf. |

|

|

| (1898)* - Photo shows the business end of the mammoth wharf in Santa Monica. Several fully loaded railcars can be seen. |

Historical Notes The Long Wharf’s prominence was short-lived due to intense political and commercial rivalry known as the "Free Harbor Fight." Huntington and Jones used their influence to delay federal investment in San Pedro Bay, advocating instead for a breakwater and port facilities at Santa Monica. However, local business interests, led by Los Angeles Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis and U.S. Senator Stephen White, lobbied for San Pedro. In 1897, a federal commission led by Rear Admiral John Grimes Walker selected San Pedro Bay as the official site for the Port of Los Angeles, ending Santa Monica’s bid. |

|

|

| (ca. 1893)* - Southern Pacific wharf, 4700 feet long, for the projected Port of Los Angeles. View is from the end of the wharf towards the shore. A train is seen heading toward to end of the wharf. |

Historical Notes With San Pedro’s selection and subsequent harbor improvements, shipping traffic shifted away from the Long Wharf. The wharf ceased major shipping operations by 1913, and demolition began soon after. By 1919, the tip of the pier was removed, and the remaining structure was used as a fishing pier until its complete removal in 1933. Today, no physical trace remains, but a California Historical Landmark plaque marks the site at Will Rogers State Beach in Pacific Palisades. |

|

|

| (1894)* - A composite image showing 4 areas of the Southern Pacific Railroad Long Wharf: the wharf extending from the coast to its terminus in the ocean, ships surround the terminus and a train is visible on the tracks (middle of image); close-up of ship's prow showing anchor and figurehead of a half-nude woman (upper left); encircled by a doubly knotted rope is a docked sailing ship, on the dock are piles of dry goods (upper right); close-ups of 2 large ships (sailboat & steamer) and several smaller sailboats (lower left). |

Historical Notes n 1897, San Pedro Bay, now known as the Port of Los Angeles, was selected by the United States Congress to be the official port of Los Angeles (Port of Los Angeles) over Santa Monica. Still, the Long Wharf acted as the major port of call for Los Angeles until 1903. Though the final decision disappointed the city's residents, the selection allowed Santa Monica to maintain its scenic charm. The rail line down to Santa Monica Canyon was sold to the Pacific Electric Railway, and was in use from 1891 to 1933. Click HERE to see more in Early Views of San Pedro and Wilmington. |

|

|

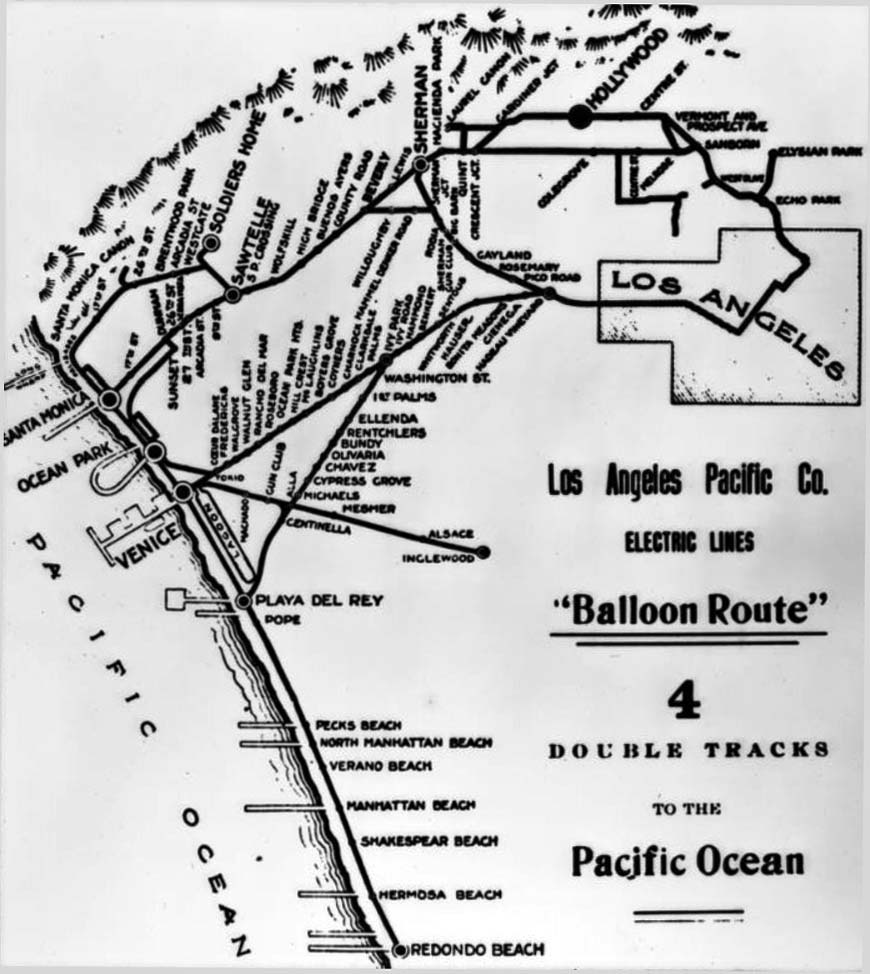

| (ca. 1911)* – Los Angeles Pacific streetcar no. 235 on the Santa Monica Long Wharf. Four men pose in front, two in uniform, with coastal cliffs visible behind—a rare view of early electric rail travel at the edge of the Pacific. Before being absorbed into the Pacific Electric system later that year, the Los Angeles Pacific Railroad operated passenger service out onto the former Southern Pacific freight wharf, once touted as “the only ocean voyage on wheels.” Tourists marveled at the novelty of riding a streetcar over open water along what was briefly the world’s longest pier. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes Tourists marveled at riding streetcars out over the ocean on the old freight wharf, promoted as “the only ocean voyage on wheels.” When Pacific Electric absorbed LAP in 1911, the line was operated as the Santa Monica Canyon Local or Port Los Angeles Line, but its function remained recreational rather than practical transit. Passenger service continued on a diminishing basis, with cutbacks in the 1920s as the wharf deteriorated and automobile tourism supplanted the red cars. By the early 1930s, only a token daily shuttle remained, and the line was formally abandoned in 1933. The last remnants of the Long Wharf were demolished that same year. Though short-lived and lightly used, the line had a notable impact on regional tourism and helped shape Santa Monica’s identity as a beach resort instead of a shipping port. |

* * * * * |

Japanese Fishing Village

|

|

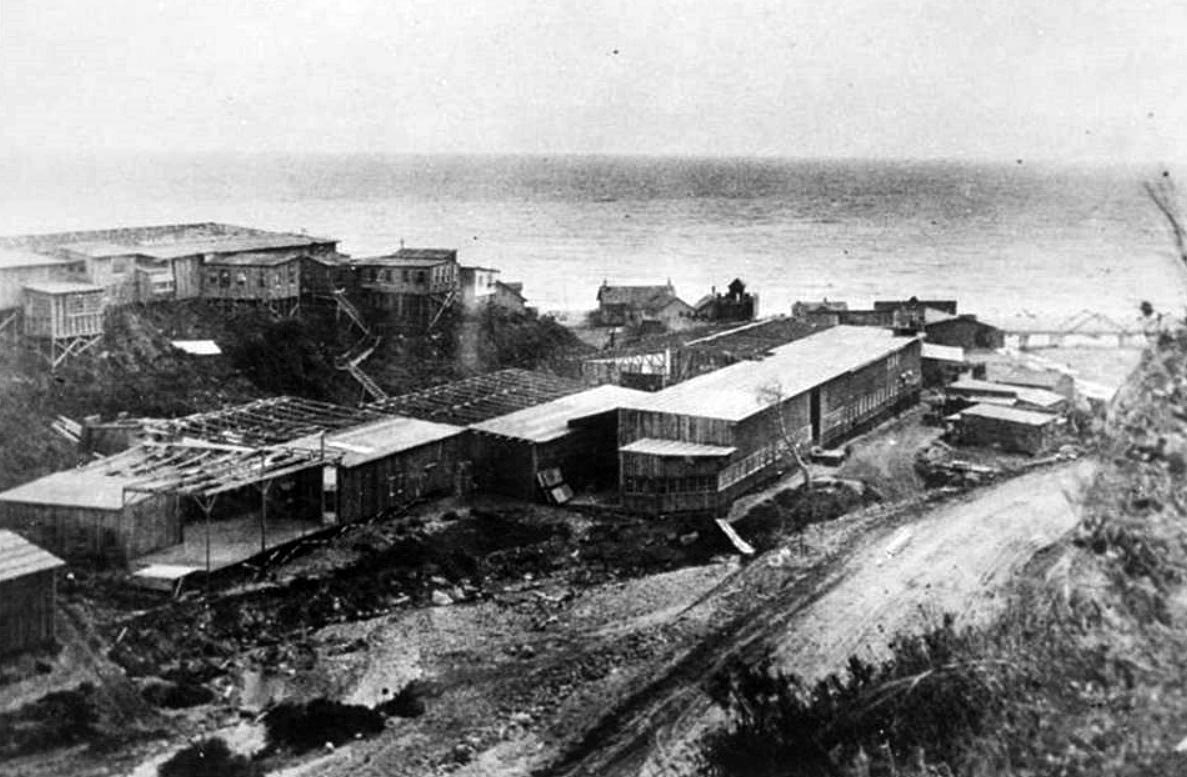

| (ca. 1915)* - Japanese fishing village north of the Long Wharf, approximately ¼ mile from Santa Monica Canyon and near today's Will Rogers State Beach. Visible on the pier are the utility poles used by the electric streetcar line—originally operated by Los Angeles Pacific Railway (LAP) and taken over by Pacific Electric in 1911. Photo by Charles C. Pierce. |

Historical Notes In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a Japanese fishing village known as Maikura was established at the foot of the Long Wharf in what is now Pacific Palisades, just north of Santa Monica Canyon. The settlement took root around 1899, led by Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) such as Hatsuji Sano, who were drawn to the area for its rich fishing grounds and proximity to the enormous, soon-abandoned wharf built by the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1893 as part of an unsuccessful attempt to establish Port Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1910s)* - Japanese fishing village located at the foot the Long Wharf north of Santa Monica Canyon. |

Historical Notes Fishing was the foundation of the local economy. Japanese fishermen supplied fresh seafood to Japanese communities in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, while others opened seafood shops and related businesses inland. The Long Wharf and the village’s seaside location also drew day visitors from the city, many of whom came to fish, dine, or enjoy the beach. The mix of hard work and cultural continuity gave the village a uniquely communal and industrious character. |

|

|