Early Views of Santa Monica

Historical Photos of Early Santa Monica |

|

|

| (ca. 1920)* - Woman with spy glass looking out toward the ocean. The beach is full of sunbathers with the Santa Monica Pier and Amusement Park in the distance. Pacific Bath House can be seen at upper right. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920)* - Woman with spy glass looking out toward the ocean. The beach is full of sunbathers with the Santa Monica Pier and Amusement Park in the distance. Pacific Bath House can be seen at upper right. Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920)* - View of the beach in Santa Monica, south of the pier. A large grassy park is in the foreground at right. Many people are seated beneath umbrellas or on blankets on the grass. A covered walkway runs through the middle of the park at right. The beach is in the background at center and is also crowded with umbrellas and people. There is a rocky outcropping in the foreground at left. In the background at right are several large buildings and a parking lot full of early-model automobiles. Part of a pier is jutting out into the water in the distance at center, and there appears to be a roller coaster in the far distance. Legible signs include, from left to right: "Ball Room", "The Rendezvous", "Ice Cream", "Tom's", and "Pacific Bath House". |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View looking north of a very crowded shoreline at Ocean Park Beach in Santa Monica. |

|

|

| (1925)* - WOW! - High density real estate. The view is looking north towards Ocean Park where some buildings and part of Lick Pier are visible. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - Crowded shoreline at Ocean Park Beach in Santa Monica. |

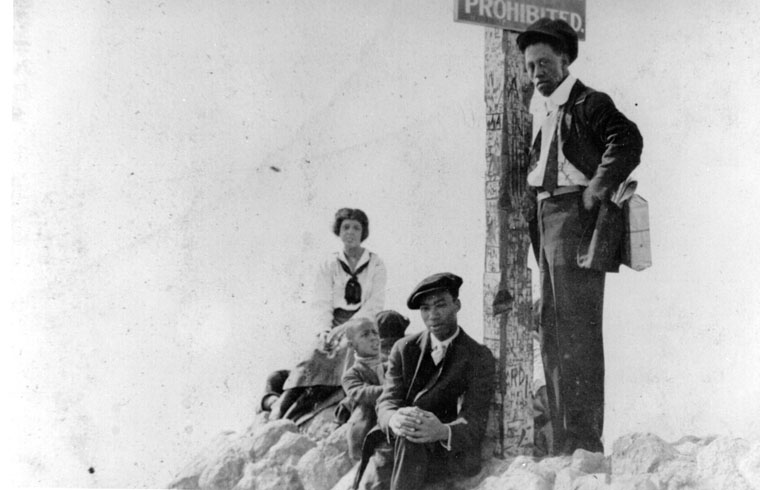

Ink Well Beach

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - A group at the sign that reads "Prohibited," at the boundary between Ink Well Beach and the whites-only section of beach in Santa Monica. |

Historical Notes Through the 1920s, many public beaches were open to whites only. For the African American community, there was a 200-sq ft. area of beach at the foot of Pico Blvd that was marked with a sign that said “Negroes Only.” This stretch of beach became known as the Ink Well. African Americans continued to congregate at the Ink Well long after racial restrictions on beach access were lifted in 1927. It continued to be a popular African American gathering spot into the 1960s. |

* * * * * |

|

|

| (1920)* - View of the beach south of Casa Del Mar Beach Club in Santa Monica, looking north to the pier. There is a grassy park at right, and the right side of the park is bordered by a covered walkway. A broad sidewalk divides the park from the sandy beach at left, and a small sidewalk electric tram is transporting passengers along the walkway. The beach is occupied by many people, several of whom are resting beneath umbrellas. The large Casa Del Mar Beach Club is at right. It is a massive rectangular building with at least five stories and a terra cotta tile roof. The pier is in the background at left. |

|

|

| (1920)* - View of the Edgewater, Breakers, and Casa Del Mar Beach Clubs in Santa Monica, looking south from the water. The three massive beach clubs are seen on the shore in the middle distance. All three buildings have at least six or seven stories and two distinct wings. A tall tower emerges from the flat roof of the club at left. Several smaller buildings can be seen between and in front of the beach clubs. The beach in front of the clubs is sparsely populated with beachgoers. The ocean in the foreground is calm. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of the Santa Monica beach and the Pacific Bath House south of Casa Del Mar Beach Club. The sandy beach stretches across the middle of the image and is crowded with hundreds of people. The Pacific Bath house is at center. It is a light-colored, two-story building with rows of rectangular windows around its perimeter. Several large beach clubs are in the distance at left, and two small eateries are at right. There is a crowded parking lot full of early-model automobiles behind the bath house. Legible signs include, from left to right, "Pacific Bath House", "Fish Dinners", "Coca Cola Sold Here", "Frost", "Christopher's Ice Cream", "Sea Food", "Creates Golden Tan", and "Prevent". |

|

|

| (1926)* - Sunbathers and umbrellas are on the sand in front of the Club Casa del Mar beach club in Santa Monica. The building displayed is the Edgewater Beach Club, 1855 Promenade. Both clubs were private. In the background is the Santa Monica Pier with its roller coaster ride. |

|

|

| (1926)* - Several people are seen relaxing at the Edgewater Beach Club, 1855 Promenade, in a covered pavilion on the beach. |

|

|

| (1927)* - Exterior view of the Edgewater Beach Club, left, at 1855 Promenade in Santa Monica. Groups of people with umbrellas are seen in front of the private beach clubs sitting on the sand and enjoying their day at the beach. The building partially visible to the right is the Club Casa del Mar. |

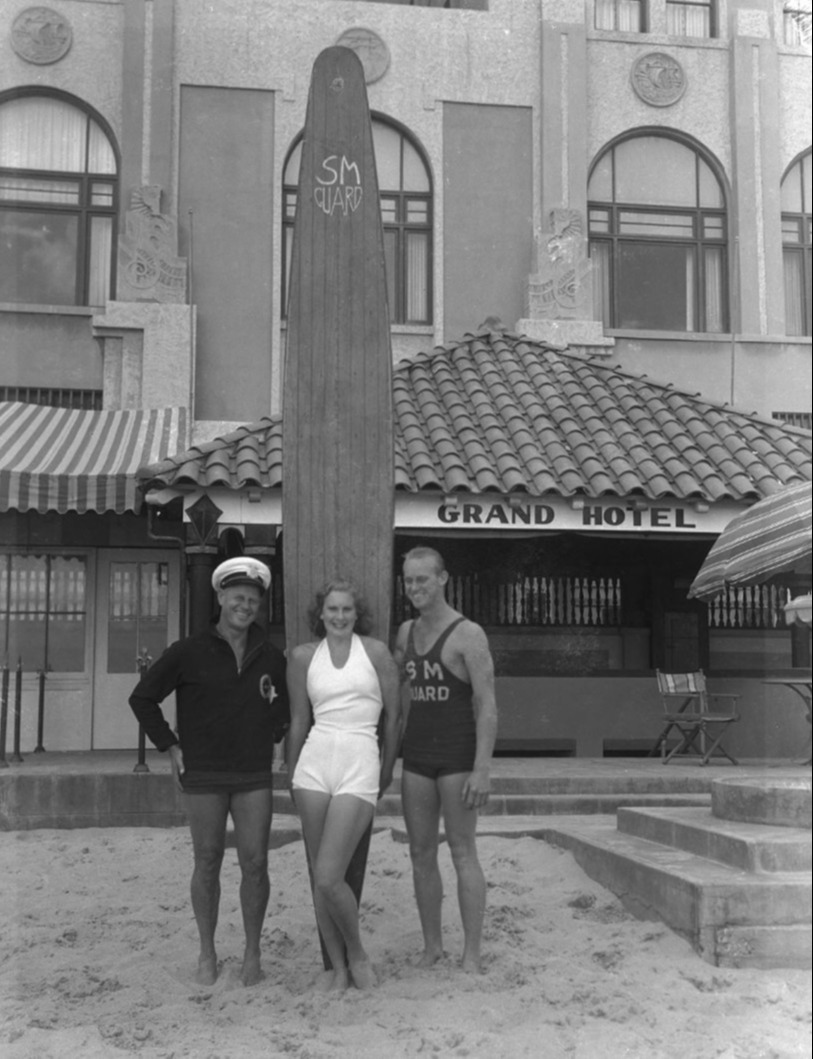

Grand Hotel (originally Breakers Beach Club, later Sea Castle Apartments)

|

|

| (1930s)* – Postcard view showing people on the beach next to the Grand Hotel with the Edgewater Club and Casa Del Mar beach clubs in the distance in south Santa Monica. The hotel at center has a large sign that reads "Grand Hotel" on the north side of the building. |

Historical Notes The Breakers Beach Club, founded in 1926, was converted into the Grand Hotel in 1934 and eventually into an apartment complex. The Edgewater Beach Club, founded in 1927, was eventually demolished. The Casa Del Mar, founded in 1926, and is currently a hotel. |

|

|

| (1932)* - Santa Monica beach, with Grand Hotel, Edgewater Beach Club, Casa del Mar, and other buildings at left. |

Historical Notes “Resort and Hotel Notes,” Los Angeles Times, 10 July 1932. The article states: The opening of the Grand Hotel on the ocean front at Pico Boulevard last Wednesday was one of the most important of early summer events in Santa Monica. Formerly occupied by an exclusive beach club the building has been remodeled and redecorated to conform to the highest of hotel standards. |

|

|

| (1930s)* - Image of the beach and surf in front of three multi-story beach clubs (from left to right): the Waverly Club, Edgewater Club and Casa Del Mar in south Santa Monica, California. The hotel in the foreground has a sign that reads "Waverly Club" on a partition on the beach. |

|

|

| (1933)* - Swimmer Helene Madison and Santa Monica lifeguards at Grand Hotel, Santa Monica, |

Historical Notes Helen Madison won three gold medals in freestyle event at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, becoming, along with Romeo Neri of Italy, the most successful athlete at the 1932 Olympics. |

|

|

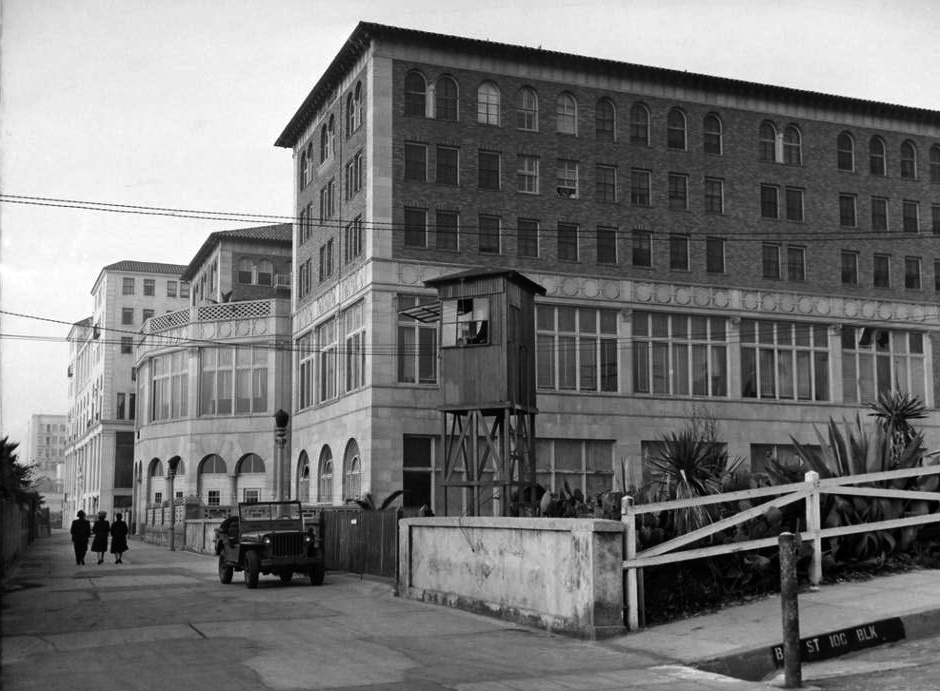

| (1944)* - The Grand Hotel, later renamed Chase Hotel, eventually became what we know today as the Sea Castle Apartments. Located on the beach in Santa Monica, between Ocean Front Walk and Appian Way, north of Pico Blvd. |

Historical Notes The Breakers Beach Club, founded in 1926, was converted into the Grand Hotel in 1934. Today it is the Sea Castle Apartments. |

|

|

| (2019)* - The Sea Castle (previously Grand Hotel) was red-tagged after the 1994 Northridge Earthquake and rebuilt to what we see above, 178-unit, 8 story apartment building. Photo courtesy of Patrick Carroll |

Historical Notes This is actually a new building which replaced the previous one. The older building was irretrievably damaged in the Northridge quake. |

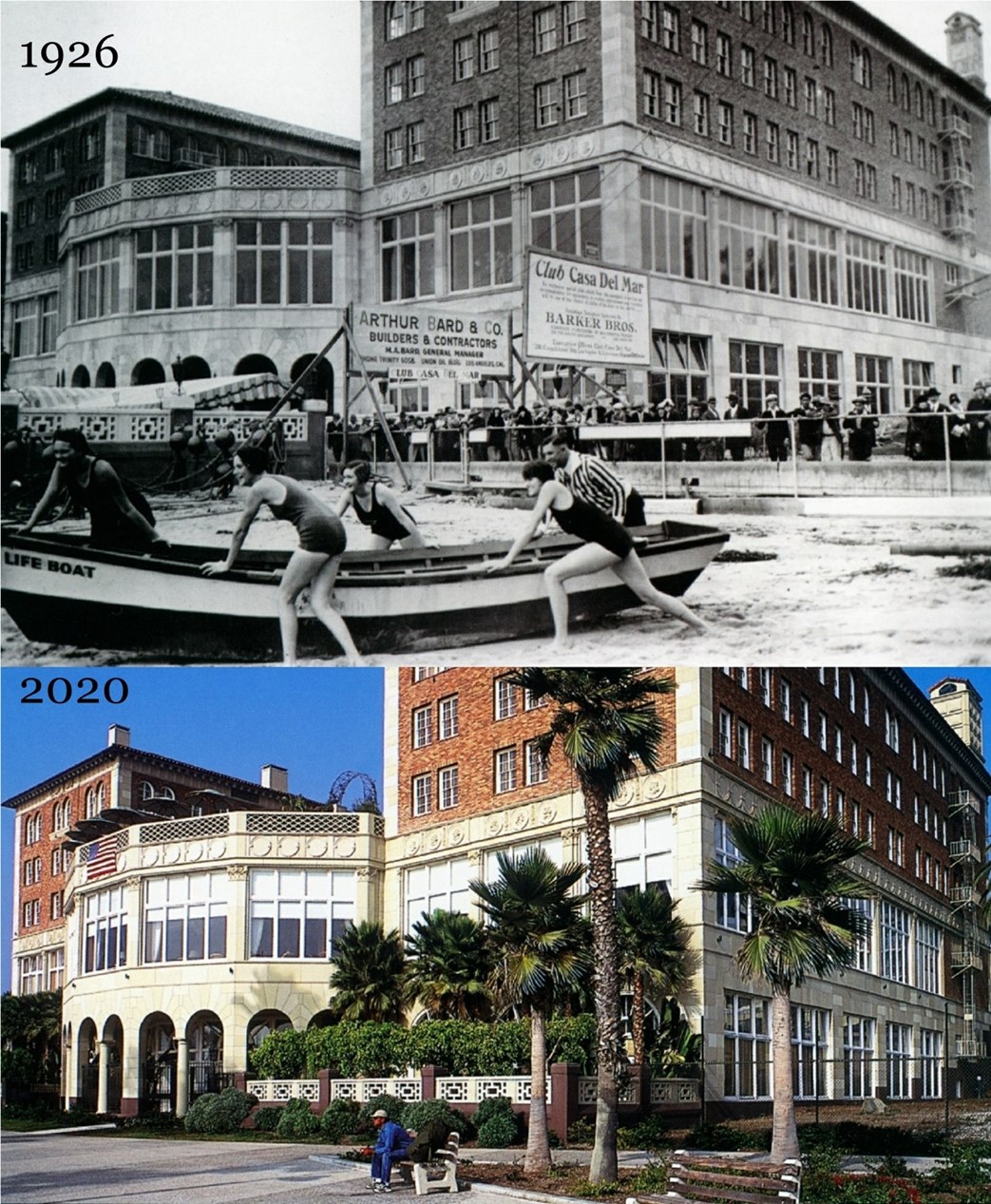

Club Casa del Mar

|

|

| (1926)* - Aerial view looking east showing the beach and Club Casa del Mar in Santa Monica. Construction of the Edgewater Club can be seen at left edge of image, north of Pico Boulevard. Huntington Library |

Historical Notes Club Casa del Mar opened in 1926 at the foot of Pico Blvd. The building was constructed by brothers E.A. "Jack" Harter and T.D. "Til" Harter, doing business as the H & H Holding Company, at a cost of $2 million. It opened as Club Casa del Mar, a private beach club, on May 1, 1926. Designed by Los Angeles architect Charles F. Plummer to reflect an Italian Renaissance Revival aesthetic. |

|

|

| (ca. 1927)* - View of the beach in Santa Monica looking north from a a full parking lot. Beyond the parking lot is a large grassy area with a covered walkway running down the middle. The Club Casa del Mar stands in the upper right. The pier in the distance is barely visible through a light fog. An electric vehicle (left-center) is seen transporting passengers along the walkway that parallels the beach. |

|

|

| (ca. 1926)* - Life boat drill with male and female lifeguards outside the new Club Casa del Mar, a private beach club at 1901 Promenade, Santa Monica. |

Historical Notes Lifeguard services were initially developed during the early 1900s in response to the rise in popularity of the beach. Several municipalities had their own service before combining forces with Los Angeles County in the 1970s, creating the world's largest professional lifeguard service. |

|

|

| (1945)^ – View showing the Del Mar Club when it was used as US Navy relocation center. |

Historical Notes In 1941, the US Navy took over the building, utilizing it for enlisted soldiers during World War II. By 1960, the hotel was shuttered. In 1967, Charles E. Dederich reopened the building as the Synanon Foundation, a drug rehabilitation program. In 1978, Nathan Pritikin turned the building into the Prikikin Longevity Center, a nutrition and health care facility that closed in 1997. |

|

|

| (1953)^ - View of the beach in front of the Club Casa del Mar. A variety of designs are on display as umbrellas cover the beach. |

Historical Notes In 1998, The Edward Thomas Hospitality Corporation acquired the building and converted it into a luxury hotel called the Casa del Mar Hotel.* The Casa del Mar Hotel is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. |

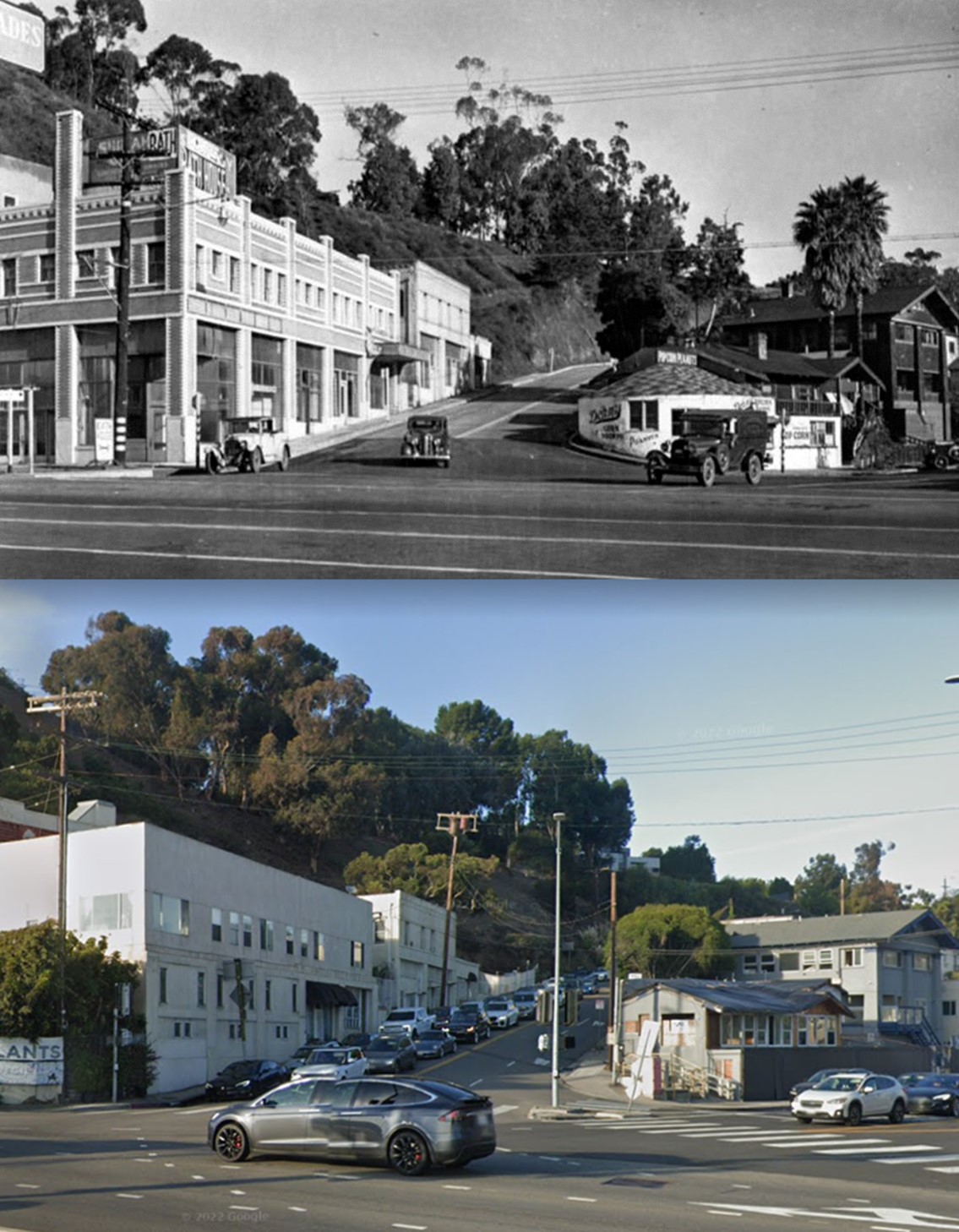

Then and Now

|

|

| Then and Now – Photo Courtesy of Augie Castagnola* |

* * * * * |

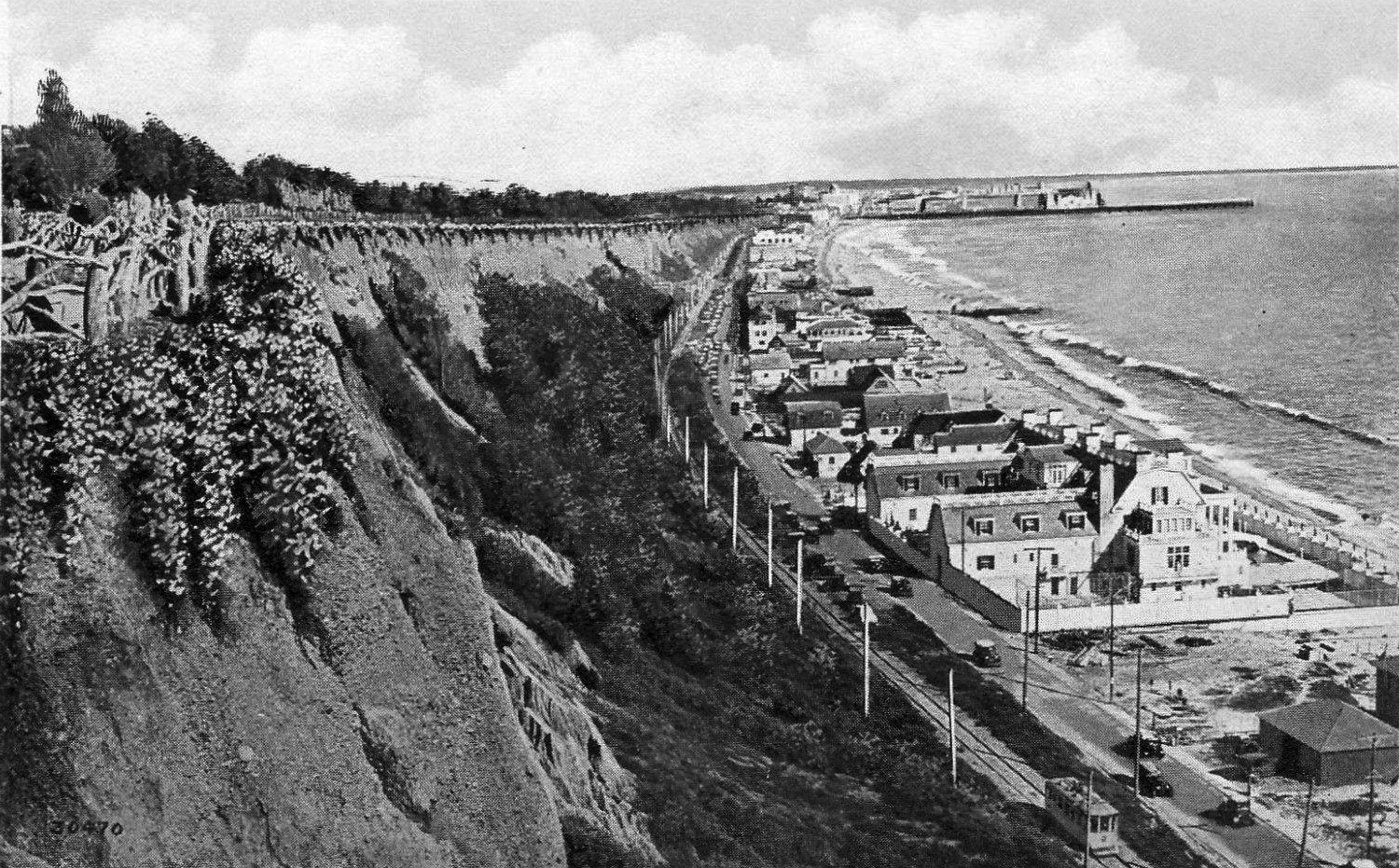

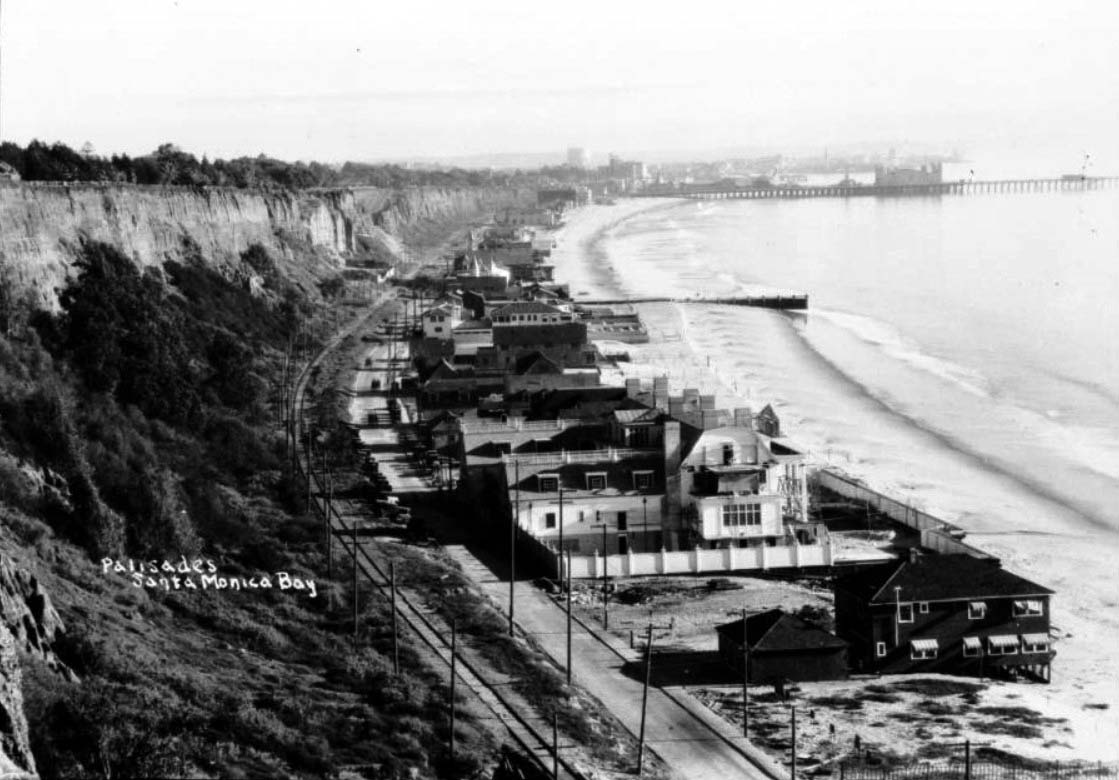

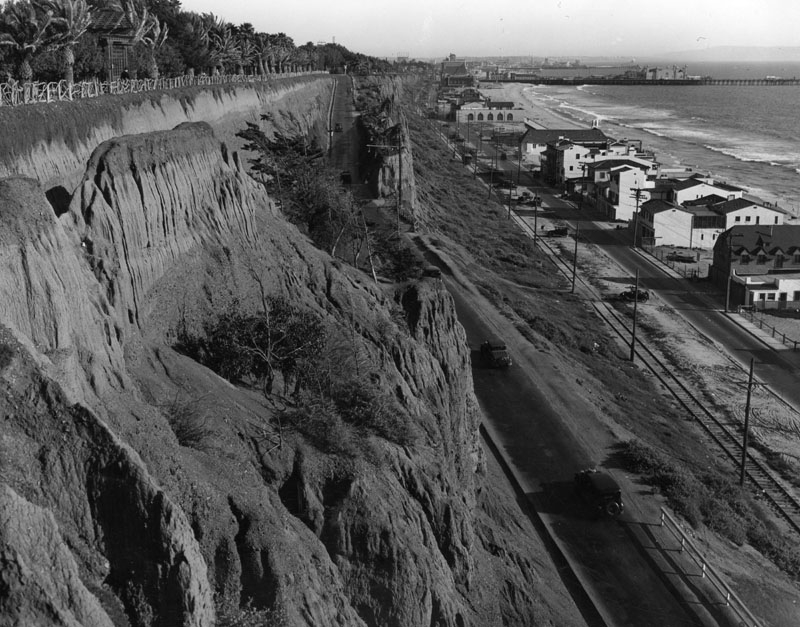

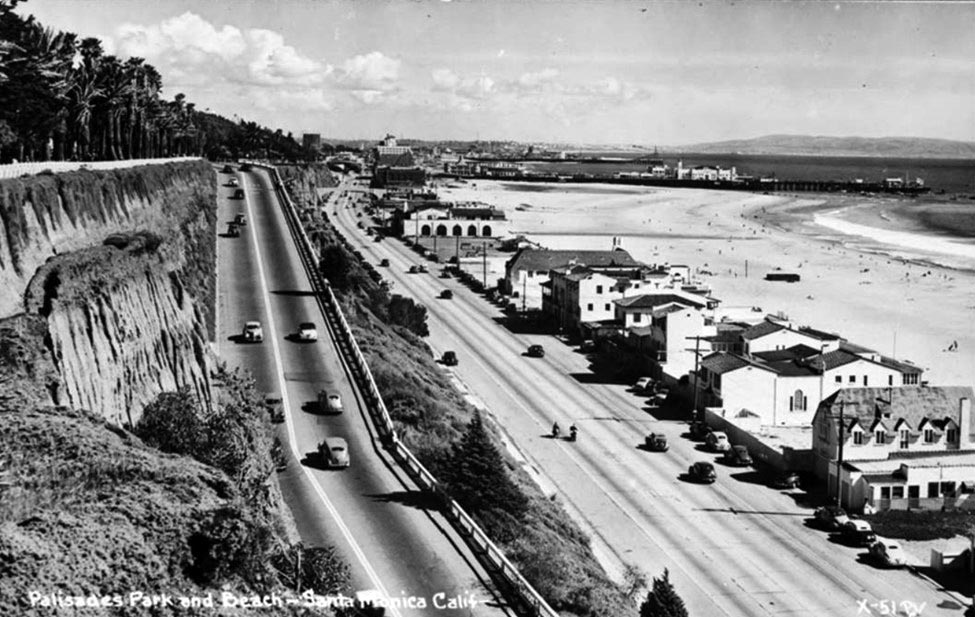

Palisades Park Views (1920s)

|

|

| (1924)* – A woman stands at the edge of the Pacific Palisades looking down at a crowded Santa Monica Beach and Roosevelt Highway. |

Historical Notes Palisades Park in Santa Monica during the 1920s was a vibrant and picturesque urban oasis overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Established in 1892, the park had evolved significantly by the 1920s, featuring a 1.6-mile stretch along Ocean Avenue with breathtaking views of both the ocean and coastal mountains. |

|

|

| (1927)* - Photo shows people on the top of the Palisades (left), which overlooks Santa Monica beach. The buildings, cars parked along the highway, and the crowds on the beach can be seen. The pier and amusement park is in the background. A new concrete staircase is seen that connects the top of the palisades to the beach. |

Historical Notes The steps and bridge seen in the above photo are at the same location as the original '99 Steps" built in 1875. When the Pacific Coast Highway was built in 1927, new concrete steps and a bridge over the highway were built to allow for continued beach access. Click HERE to see more on the original 1875-built '99 Steps". |

|

|

| (1927)* – Looking down from Palisades Park at Beach Road (later Roosevelt Highway and Pacific Coast Highway), with cars parked along the tracks. To the right is the Santa Monica Athletic Club. In the distance, the Santa Monica Pier features the Whirlwind Dipper roller coaster and La Monica Ballroom. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes Beach Road in Santa Monica became Roosevelt Highway in 1927. The road was then renamed Pacific Coast Highway (PCH) in 1941. |

* * * * * |

|

|

| 1927)* - View of Ocean Avenue shows many cars parked on one side of the road. A trolley can be seen in the distance. |

|

|

| (1928)* - Bird's-eye view of Main Street and surroundings, looking west-northwest toward Ashland Avenue, showing businesses, cars, pedestrians, and houses, with Santa Monica Pier in background. |

* * * * * |

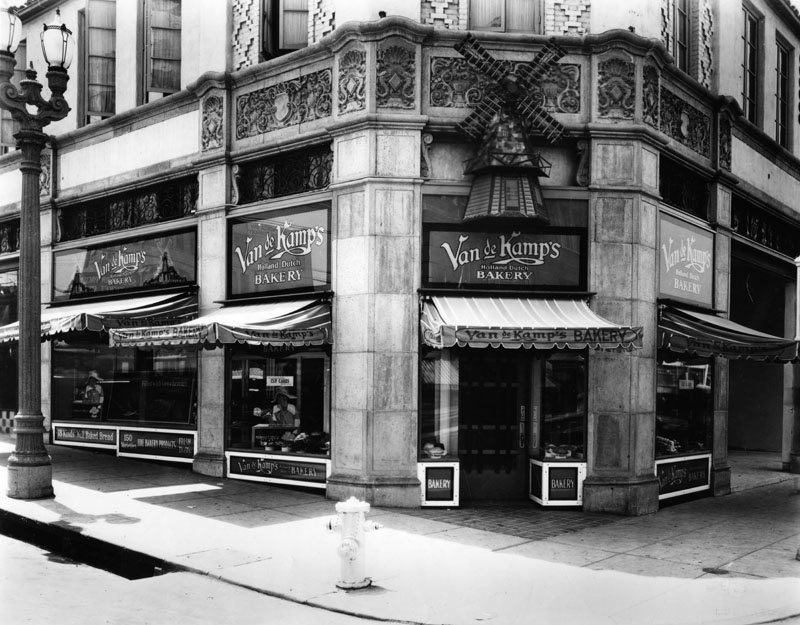

Van De Kamp's

|

|

| (1929)* - An exterior corner view of the Parkhurst Building which here housed the Van De Kamp's Bakery on the bottom floor. Located at 185 Pier Ave. in Ocean Park. |

Historical Notes Built in 1927, the Spanish Colonial Revival style building was designed by architects Marsh, Smith & Powell. Norman F. Marsh also planned the arcaded streets and canals of Venice. |

|

|

| (2008)*^ - View of the Parkhurst Building as it appeared in 2008. The sign on the front door reads: "Planet Blue". |

Historical Notes The Parkhurst Building was included in the National Register of Historic Places, California Register of Historic Places and designated as a Santa Monica landmark. |

* * * * * |

Douglas Company Plant

|

|

| (1922)* - Aerial view of the buildings of the Douglas Company plant (incorporated as the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1928) and surrounding fields along Wilshire Boulevard in Santa Monica, with a DT-2 biplane parked next to the main building. The Douglas Company leased the abandoned film studio buildings of the Herrman Film Corporation in 1922. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes Founded by Donald Wills Douglas Sr. in 1921, the Douglas Aircraft Company began in a small facility on Wilshire Boulevard at 25th Street in Santa Monica. Initially operating as the "Douglas Company," its early operations were modest, with the company even starting out in the back of a barbershop. In 1922, as the company sought to expand, Douglas Aircraft leased the abandoned film studio buildings of the Herrman Film Corporation. This move provided the company with additional space and resources to grow its operations. The expanded facilities proved crucial as the company worked on one of its most significant early achievements: the production of the Douglas World Cruiser. |

|

|

| (1925)* - Aerial view of the buildings of the Douglas Company plant and surrounding fields and buildings along Wilshire Boulevard in Santa Monica, with billboard advertisements visible along the fence at right. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes In 1924, the Douglas World Cruiser became the first aircraft to successfully circumnavigate the globe, a feat that brought the company international recognition and established it as a major player in the aviation industry. Despite the success, the limitations of the Wilshire Boulevard and leased Herrman Film Corporation facilities soon became apparent as the company's military contracts and production demands grew. By the late 1920s, the need for a larger and more strategically located facility led Douglas Aircraft to relocate to Clover Field in Santa Monica. This move allowed the company to expand its production capabilities and continue its trajectory of success, but the original plant remains a significant part of the company's early history, marking the humble beginnings of what would become a powerhouse in the aerospace industry. |

|

|

| (2020s)* - Google Earth view looking down at the Douglas Park on Wilshire Boulevard and 25th Street in Santa Monica. This was the sight of the Douglas Company Plant from 1920 to 1927. |

Historical Notes Douglas Park in Santa Monica has a rich history that reflects its transformation from an industrial site to a cherished public space. Originally, the land where Douglas Park is located was used as an aircraft factory for the Douglas Aircraft Company, founded by Donald Douglas. The site also served as a movie studio lot. However, due to the limitations posed by the surrounding trees, which affected aircraft takeoff, the factory operations were moved to Clover Field (now Santa Monica Airport) in 1927. Following the relocation of the factory, the city of Santa Monica decided to repurpose the land into a public park. The park's design was entrusted to architect Ed Howard, and construction took place between 1931 and 1933. Initially named Padre Park, it was later renamed Douglas Park in honor of Donald Douglas. Douglas Park spans 10.7 acres and features a variety of recreational facilities. These include two tennis courts, picnic areas, a children's playground, a clubhouse, and a lawn bowling green that hosts the Santa Monica Bowls Club. The park is also home to three reflecting pools and the largest municipal pond in Los Angeles County, supporting a diverse ecosystem of ducks, turtles, and fish. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1925 vs. 2020)* - Aerial view looking north over Wilshire Boulevard and 25th Street in Santa Monica, showing the Douglas Aircraft Company Plant, which is now the site of Douglas Park. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

* * * * * |

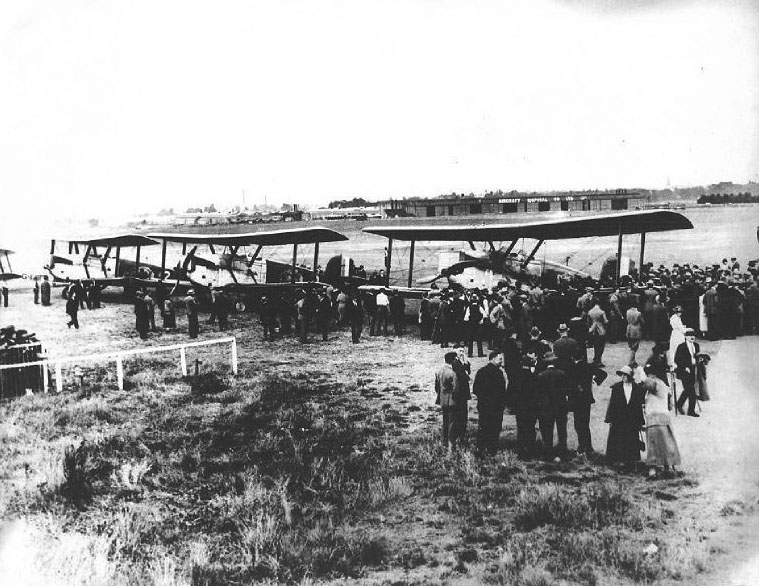

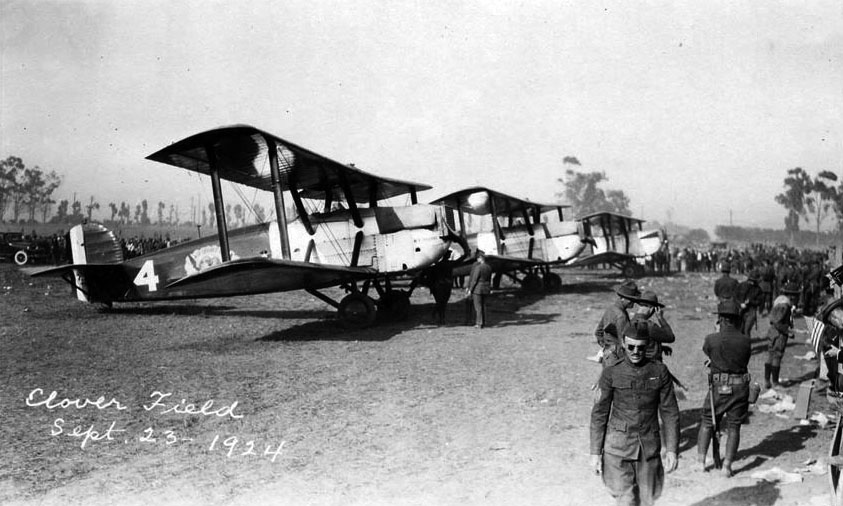

Clover Field (later Santa Monica Airport)

|

|

| (ca. 1924)* - Aerial view of Clover Field Airport in Santa Monica, showing residences in the distance. Hangars and other buildings are seen at center, amidst large expanses of open land. Several airplanes sit in the grass in front of and to the left of the buildings. A row of trees sits behind the building, running diagonally across the upper left corner of the image. |

Historical Notes As early as 1917, aviators were landing on this grassy runway perched atop a mesa just southeast of Santa Monica. It was surrounded by stalks of barley. Soon the landing strip became a military airfield, and in 1922 the U.S. Army named it Clover Field in honor of Greayer Clover, a fighter pilot killed in France during the First World War. Since then the site has served many purposes. First it was the western headquarters of the Army’s reserve air corps, and later Douglas Aircraft produced its line of DC planes there. |

|

|

| (1924)#+# - A growing crowd of spectators at Clover Field inspect the World Cruisers before their epic flight. |

Historical Notes Douglas World Cruiser biplanes are the first aircraft to circumnavigate the globe in the weeks between April and September. The U.S. Army with Douglas World Cruisers, took off from Clover Field on St. Patrick’s day, March 17, 1924, and returned there after some 28,000 miles. |

|

|

| (1924)* - "Douglas World Cruisers return to Clover Field, Santa Monica, CA on September 23rd, 1924." |

Historical Notes Two planes made it back, after having covered 27,553 miles in 175 days, and were greeted on their return September 23, 1924 by a crowd of 200,000 (generously estimated). |

|

|

| (1929)* – View showing some of the female aviators who competed in the first women’s transcontinental air derby which began in Santa Monica on August 18, 1929. Amelia Earhart is fourth from the right. Louise Thaden, who won the 2700-mile race, is fifth from the right. |

Historical Notes In August 1929, seventy women held a United States pilot’s license. Of those, twenty young female aviators assembled at Clover Field on the afternoon of August 18 to take part in the groundbreaking competition. Navigating the 2700-mile course with only road maps on their laps, the women flew from Santa Monica to Cleveland via stops in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois and Indiana. Along the way, there were continuous mishaps and a constant need for maintenance. Some competitors were forced to drop out of the race. Florence “Pancho” Barnes and Ruth Nichols crashed their aircraft. Margaret Perry contracted typhoid fever. Claire Fahy’s plane was found to have suspicious mechanical damage. Sadly, pilot Marvel Crosson, who had just set an altitude record at 23,996 feet the previous May, perished in a tragic crash. The race continued despite these perils, malfunctions and calamities. And at every stop, enthusiastic crowds gathered to meet the female flyers they had read about in the press. At the Cleveland Municipal Airport, a throng estimated at 18,000 people greeted the pilots as they finished the race. Louise Thaden came in first, and she was followed by fourteen others: Amelia Earhart, Ruth Elder, Edith Foltz, Mary Hazlip, Jessie Keith-Miller, Opal Kunz, Blanche Noyes, Gladys O’Donnell, Phoebe Omlie, Neva Paris, Thea Rasche, Bobbi Trout (finished untimed because of two forced landings), Mary von Mach, and Vera Dawn Walker. The Air Derby set the stage for other major air race competitions for women and supported the notion, highly suspect at the time, that women could be accomplished pilots. The race also strengthened the bonds between the participants and inspired them to organize. A few months later in 1929, most of these female aviators became founding members of The Ninety-Nines, an organization of licensed women pilots founded to promote and support women in aviation. |

|

|

| (1929)* - Crowds gathered on the sides of Clover Field (Santa Monica Airport) to watch the air show. Several planes are parked on the field, waiting their turns to takeoff. |

Historical Notes On June 15, 1927 Santa Monica City Council changed the name of Clover Field to Santa Monica Airport (SMO). In 1928, the City acquired an additional 60 acres to expand the Airport and to accommodate an expanding Douglas plant. |

|

|

| (1929)* - View showing the Santa Monica Airport (previously named Clover Field). The Douglas Aircraft plant can be seen on the right. |

Historical Notes Donald Wills Douglas, Sr. founded the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1921 with his first plant on Wilshire Boulevard. He built a plant in 1922 at Clover Field (Santa Monica Airport), which was in use for 46 years. In 1924, four Douglas-built planes took off from Clover Field to attempt the first aerial circumnavigation of the world. Two planes made it back, after having covered 27,553 miles in 175 days, and were greeted on their return September 23, 1924 by a crowd of 200,000 (generously estimated). In 1929, Douglas enlarged its Santa Monica Airport operations, closed other facilities, and began to develop its early DC-2 and DC-3 airliners as well as other projects. |

|

|

| (1930s)* – Close-up view of the original three big hangars on the north side of Clover Field. The large hangar at the back is the first Douglas Aviation hangar on the field, circa early 30's. |

|

|

| (1940)* – Aerial view of the Santa Monica Airport looking towards the southeast with the Douglas plant filling the bottom half of the photo. Photo Date: August 7, 1940 |

Historical Notes Between 1941 and 1944 (During World War II), Douglas Aircraft becomes a major defense contractor, employing up to 44,000 workers who work three shifts, seven days a week. This economic engine transforms the city as thousands of new homes are built for the Douglas workers, creating Sunset Park and other neighborhoods. |

|

|

| (1940s)* - View of Douglas Aircraft with numerous planes positioned all around its plant. The surrounding neighborhood has been built up when compared to previous photo. |

Historical Notes Douglas Aircraft Co. was a major player in the aircraft industry during World War II. Local historians note that World War II affected Santa Monica more than most places, as the Federal Government (for national security reasons) leased the Airport from the City to provide protection for Douglas Aircraft – then a major defense contractor located in Sunset Park. The government also participated in the expansion of the facility to accommodate the ever-growing production of military aircraft by Douglas Aircraft. |

|

|

| (1940s)* – View showing night production of fighters at Douglas Aircraft Company's assembly plant in Santa Monica. |

Historical Notes Santa Monica CA- Along brilliantly lit assembly lines of Douglas Aircraft Company’s plant here, night crews are rushing production of DB-7B attackers bombers, recently acclaimed as night fighters in the defense of blacked out Britain. Equipped with heavy armament self-sealing fuel tanks and armor plating, these ships are proving swift and deadly in interception and downing Nazi raiders. R.A.F. early designated the DB-7 type the Boston and more recent the Havoc. Under a backlog in excess of $400,000,000 nearly 28,000 Douglas employees are working around the clock on attack ships, dive bombers and military transports for Americans and Britain. |

|

|

| (ca. 1940)* - An impatient car starts across the crosswalk while men and women are still crossing towards the Douglas Aircraft Company factory, located at 2700 Ocean Park Boulevard, Santa Monica. An ice cream truck is parked and the attendant is ready to catch workers as they return to work. |

Historical Notes At its peak, Douglas Aircraft, and Santa Monica Airport grew in size to its present 227 acres, employing 40,000 individuals. |

|

|

| (ca. 1945)* - Playing such a vital role in military aircraft production during World War II, camouflage was used to make the plant and airstrip disappear - at least from the air. |

Historical Notes During the war the airport area was cleverly disguised from the air with the construction of a false "town" (built with the help of Hollywood craftsman) suspended atop it. |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)* – Santa Monica Airport with the Douglas Aircraft plant seen at right. |

Historical Notes Clover Field (Santa Monica Airport) was once the site of the Army’s 40th Division Aviation, 115th Observation Squadron and became a Distribution Center after World War II. |

|

|

| (1953*- Douglas DC-3, DC-4, DC-6, DC-7 lined up on the NE end of the Santa Monica Airport. The view is looking towards the east. |

|

|

| (1967)* – Aerial view looking west toward the Pacific Ocean showing Santa Monica Airport. The Douglas Aircraft plant is on the right. |

Historical Notes In later years, Douglas Aircraft merged with a rival to become McDonnell-Douglas Corporation (1967) and moved to Long Beach (1976). The 5,000-foot runway at what was by then known as Santa Monica Airport was too short for the firm's growing jet production. Two decades later, McDonnell-Douglas would be absorbed by yet another rival, Boeing Company. When the corporation left town, Douglas' son, Donald Wills Douglas Jr, set up the Donald Douglas Museum and Library to commemorate his father's legacy. Douglas Sr. died in 1981. Nine years later, the nonprofit Museum of Flying, founded by golf course and real estate developer David Price, superseded the old museum as part of a $20-million airport overhaul. Exhibits included vintage planes and an immense photo of when the airport and plant operated under cover of camouflage. |

|

|

| (2014)* - Santa Monica Airport (SMO) as it appears today. |

Historical Notes On January 28, 2017, it was announced that Santa Monica City officials and the Federal Aviation Administration had reached an agreement to close the Santa Monica Airport on December 31, 2028 and return 227 acres of aviation land to the city for eventual redevelopment. It is anticipated that the airport land will be redeveloped into areas for parks, open space, recreation, education and/or cultural use. In an attempt to reduce jet traffic, the city planned to shorten the runway from 4,973 feet to 3500 feet by repainting the runway and moving some navigational aids. The shortening has been formally completed as of 2017 December 23. |

Click HERE to see more in Aviation in Early L.A. |

* * * * * |

|

|

| (1930)* - A view down the street showing the parade marchers, floats and spectators of the Baby Parade of 1930 as they march past the Ocean Park Plunge near the beachfront. |

Roosevelt Highway Opening (Last Section)

|

|

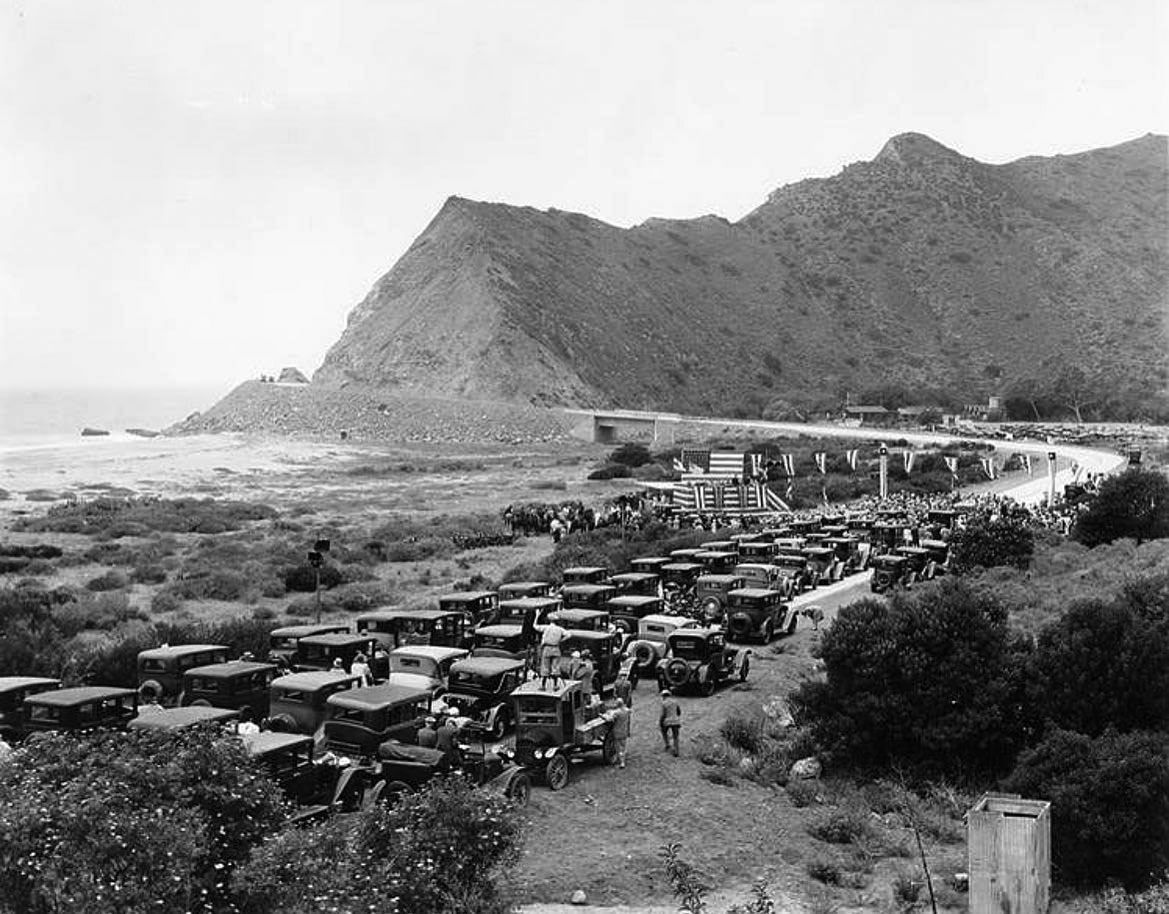

| (1929)#* – Aerial view showing the opening ceremonies of the Roosevelt Highway through Malibu. This was the last section of the highway linking Mexico with Canada. The Roosevelt Highway today is the Pacific Coast Highway. Photo taken from the Goodyear airship Volunteer and published in the June 30, 1929, Los Angeles Times. |

Historical Notes LA Times Article dated June 30, 1929 reads: For the first time in more than a century the general public was today given access to the scenic wonders of the famous Malibu Ranch when the last link in the Roosevelt Highway, extending from Canada to Mexico, was formally opened and dedicated by Gov. Young at ceremonies in Sycamore Canyon, near the Ventura-Los Angeles county line. |

|

|

| (1929)#* – First Sig Alert on the PCH? An aerial photo shows cars waiting for opening ceremonies on the Roosevelt Highway through Malibu, the last section of the highway linking Mexico with Canada. |

Historical Notes A motor caravan of 1500 cars filled with representatives of various organizations which have labored long and hard that this highway might be built left the Chamber of Commerce at Santa Monica at 9:30 o’clock this morning. The procession wended its way north to the canyon, where an arch was constructed on the highway. - LA Times, June 30, 1929 |

|

|

| (1929)#* - A crowd of dignitaries attends a ceremony opening the Roosevelt Highway through Malibu. |

Historical Notes Gov. Young, after a short speech in which he related some of the handicaps overcome in construction of the road, gave the signal to the young lady representatives of Canada and Mexico, who applied lighted tapers to an explosive so placed that its explosion severed a barrier across the highway. - LA Times, June 30, 1929 |

|

|

| (1929)* - Opening of Roosevelt Highway (PCH) in Malibu. |

Historical Notes The coast highway was formally dedicated as the 'Theodore Roosevelt Highway' when it was completed in 1929 and was generally known as the 'Roosevelt Highway' or 'Coast Highway' in the 1930s. It was designated as US 101A (Alternate) in 1936. State legislative action in 1964 changed many highway numbers in California, and US 101A became CA 1. In the same year, the state legislature offically named CA 1 'Pacific Coast Highway' in Orange, Los Angeles and Ventura Counties. |

|

|

| (1929)* - Photo shows "two views of the picturesque Santa Monica-Oxnard link of the Coast highway opening today, winding about the hills along the sunset shore." Photograph dated: June 29, 1929. |

Historical Notes The section of Highway 1 from Santa Monica to Oxnard, via Malibu, went out to contract in 1925 as "Coast Boulevard" but was designated "Theodore Roosevelt Highway" when it was dedicated in 1929. The Highway 1 designation was first designated in 1939. Various portions of State Highway 1 have been posted and referred to by various names and numbers over the years. State construction of what became Highway 1 started after the state's third highway bond issue passed before 1910.*^ |

|

|

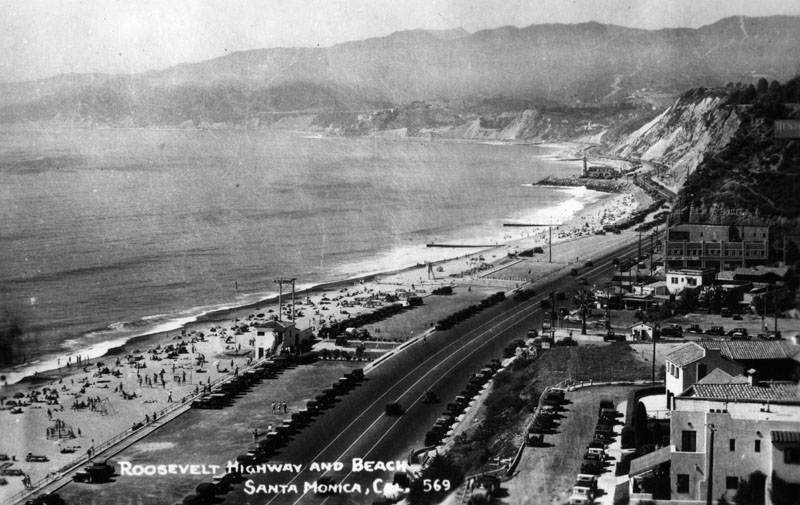

| (ca. 1930)* - View of the coastline along Pacific Coast Highway looking north to Santa Monica, Pacific Palisades and Malibu. |

Historical Notes This is a photograph of a Chris Siemer painting created for a display by the L.A. Chamber of Commerce. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)* - Panoramic view showing the Roosevelt Highway running along the coastline of Santa Monica beach. The landmark Pacific Palisades Lighthouse, Bathhouse, and Restaurant at the location of the original Long Wharf can be seen in the distance. |

|

|

| (1931)** – Winter view of the Pacific Palisades along the Roosevelt Highway, looking north from the Santa Monica Palisades, showing the landmark lighthouse and bathouse. Photo date: February 26, 1931. |

|

|

| (ca. 1958)#*#* - Aerial view showing the Light House Restaurant (1927 - 1972) and Carl's at the Beach across Pacific Coast Highway, Santa Monica, at the location of the original Long Wharf (1893 - 1920). |

Carl's at the Beach (aka Carl's Sea-Air Motel, Carl's Sea-Air Lodge, and Sunspot Motel)

|

|

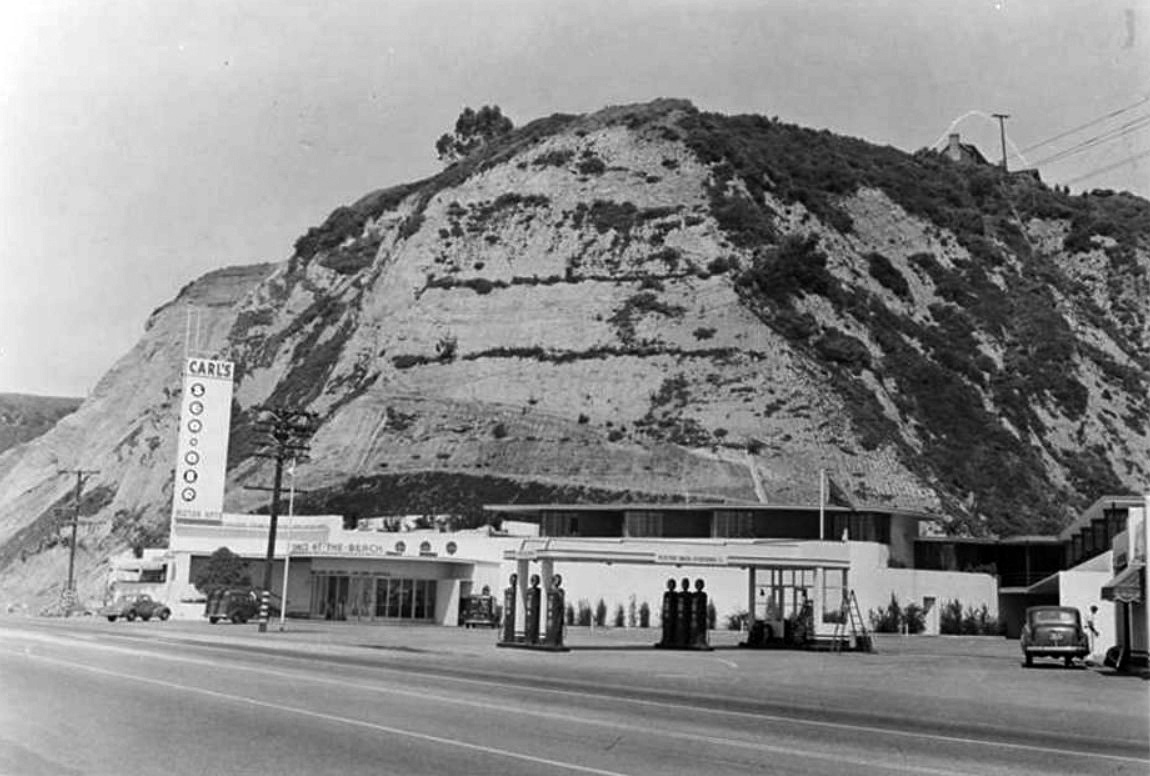

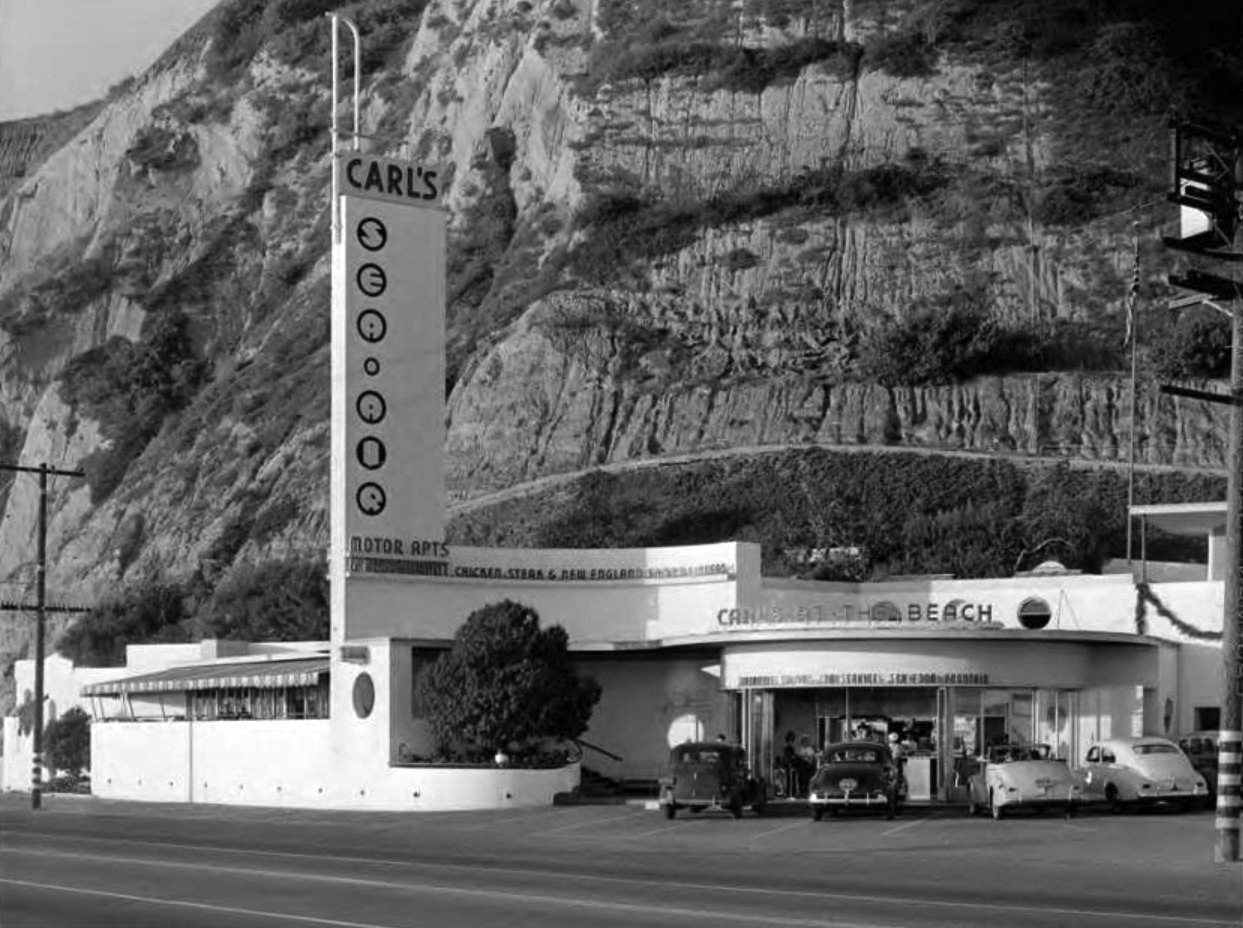

| (ca. 1938)*#^ - Carl's-at-the-Beach Motel (later the Sun Spot Motel) on Pacific Coast Highway, one of the oldest motels in California. The motel was located across the street from the landmark Pacific Palisades Lighthouse, Bathhouse, and Restaurant. |

Historical Notes The 12-room motel, designed in 1930s by two prominent Los Angeles architects, Burton Alexander Schutt and A. Quincy Jones, was among the first to offer a full range of services--from restaurant to gas station to garage space--for Americans beginning their love affair with the car and the open road.^ |

|

|

| (1947)#*#* – View showing Carl's-at-the-Beach motel complex which included a drive-in restaurant. Photo by Julius Shulman |

Historical Notes This motel was different--a streamlined V-shaped building, its two wings nestled snugly against the line of the bluffs where Potrero Canyon opens to the ocean. The public areas were close to the road, the sleeping rooms on a second story away from the traffic streaming by on what was then known as Roosevelt Highway. Motel guests, shielded from the cars' noise and fumes, could relax in the rear garden and look at the canyon beyond. Or they could gaze out the angled front windows of their rooms at a sweeping ocean vista.^ |

|

|

| (1940s)^x^ - Full house at Carl's-at-the-Beach Drive-in Restaurant and motel complex. |

|

|

| (1940s)#^^ – Close-up view showing Carl's Drive-in at the Sea Air Lodge complex (aka Carl's-at-the-Beach) |

Historical Notes Drive-in Restaurants flourished in Southern California during the 1930s and 40s. Click HERE to see more Early LA Drive-in Restaurants. |

|

(1940s)^x^ – Looking over the roofline of Carl’s-by-the-Beach Drive-in towards the ocean. |

|

.jpg) |

|

| (1947)#*#* - View showing Carl's at the Beach Motel (later known as the Sunspot), a 12-room motel, designed in 1938. The car parked on the left is a beautiful 1941 Buick two-door sedanette. Photo by Julius Shulman |

Historical Notes By the mid-1970s, the property at the foot of the Pacific Palisades bluffs had evolved into the Sunspot, a bar and mecca for the disco dance craze. The Sunspot complex was closed in the 1980s and sat empty for nearly 10 years. The Los Angeles Recreation and Parks Department, which owned the property, hoped eventually to renovate and lease the building as a motel and restaurant. However in 1994 a landslide crushed the westerly portion of the building—the part that would have been the restaurant. Since then the City has demolished what was left of the buildings.^ |

* * * * * |

Will Rogers State Beach

|

|

| (1930s)* - View from the bluffs, looking North to Will Rogers State Beach and Pacific Coast Highway. |

Historical Notes The beach is named after actor Will Rogers. In the 1920s, Rogers bought the land and developed a ranch along the coast. He owned 186 acres along the coast in what is now Pacific Palisades. Rogers died in a plane crash in 1935. Then when his widow, Betty, died in 1944, the ranch became a state park. The Will Rogers State Beach lifeguard headquarters is the site of the former Port of Los Angeles Long Wharf, a California Historical Landmark, site number 881.^ |

Chautauqua Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway

|

|

| (mid-1920s)^x^ - View looking south on Roosevelt Highway at the intersection with Chautauqua Boulevard and Channel Road. A 'Barbecue' restaurant can be seen on the southeast corner. The crowded beach to the right will become Will Rogers State Beach in 1944. |

Historical Notes Will Rogers Beach was donated to the State of California by his widow, Betty, in 1944. The County of Los Angeles has been operating the beach since 1975.^ Note the old tracks on Roosevelt Highway are still there in the above photo. The railroad tracks were removed when Roosevelt Highway was widened in 1934. |

|

|

| (1930s)* - View shows Roosevelt Highway (now PCH) running parallel to the Santa Monica beach at the intersection with Chautauqua Boulevard. Cars parked along the sides of the highway and crowds on the beach can be seen. A bath house sign, several restaurants and a couple of gas stations are on the left side. The Santa Monica pier can be seen in the distance. |

|

|

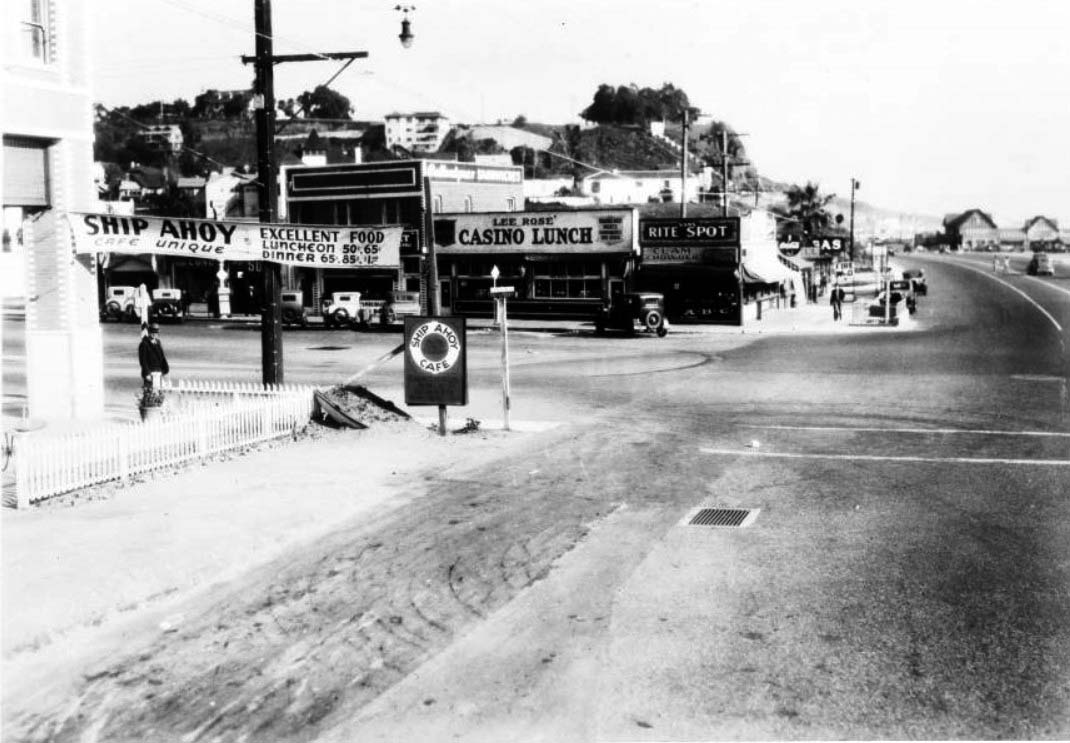

| (1930s)** – Close-up view of the intersection of Chautauqua Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica. The highway extends into the distance at right while Chautauqua runs from left to right. There are several buildings visible on the sides of Chautauqua, and many early-model automobiles are parked along the side of the road. A man is standing in the foreground at left, holding a basket, and several other pedestrians are visible in the distance at right. A hill covered with large houses can be seen in the distance at left. Legible signs include, from left to right: "Ship Ahoy Cafe Unique Excellent Food Luncheon 50 65 Dinner 65 85 $1.00", "Ballanlymes Sandwiches", "Lee Rose Casino Lunch Barbequed Mets Hamburger Hot Dogs", "Sam's Rite Spot", "Clam Chowder", and "ABC". |

|

|

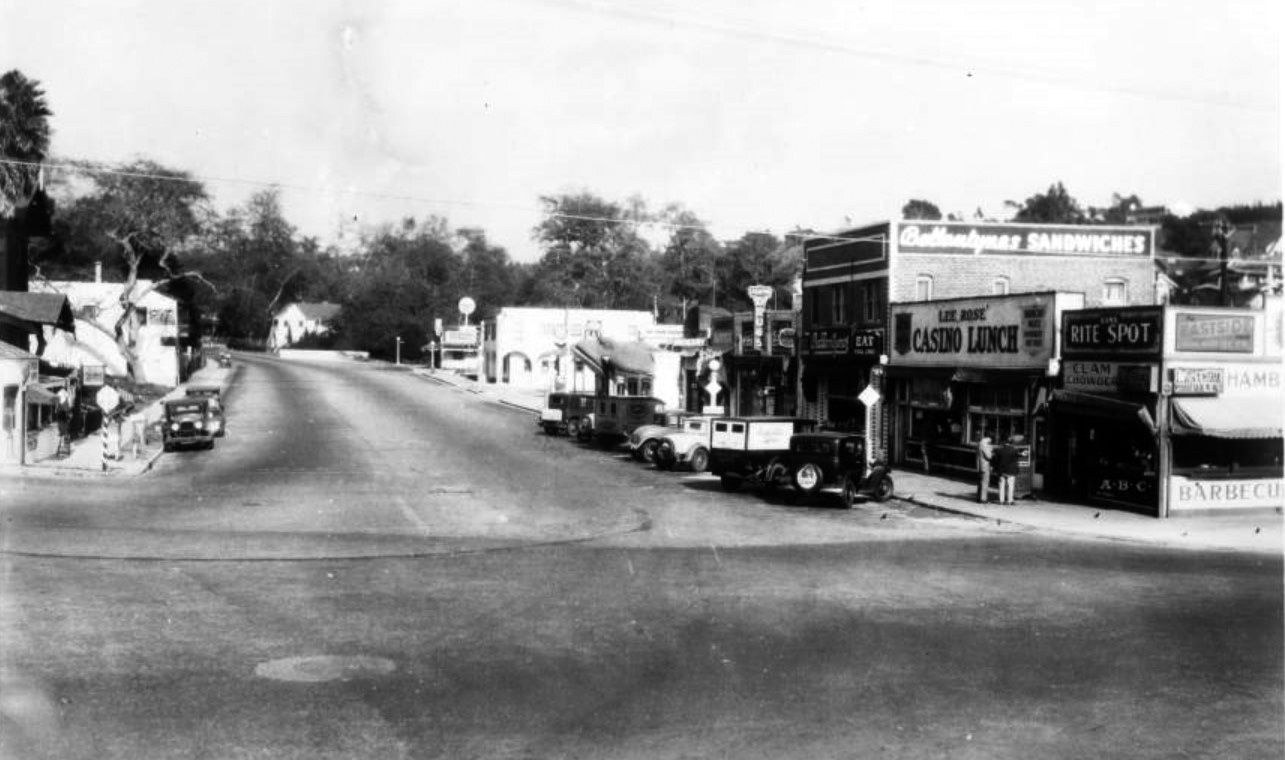

| (1930s)** - Panoramic view of West Channel Road in Santa Monica from Chautauqua Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway. Legible signs include, from left to right: "Liquor Drugs", "Grocery", "Eat Real Chili", "Ballanlymes Sandwiches", "Lee Rose Casino Lunch Barbequed Mets Hamburger Hot Dogs", "Sam's Rite Spot", "Clam Chowder", "ABC", "Eastside Beer", and "Barbeque". |

|

|

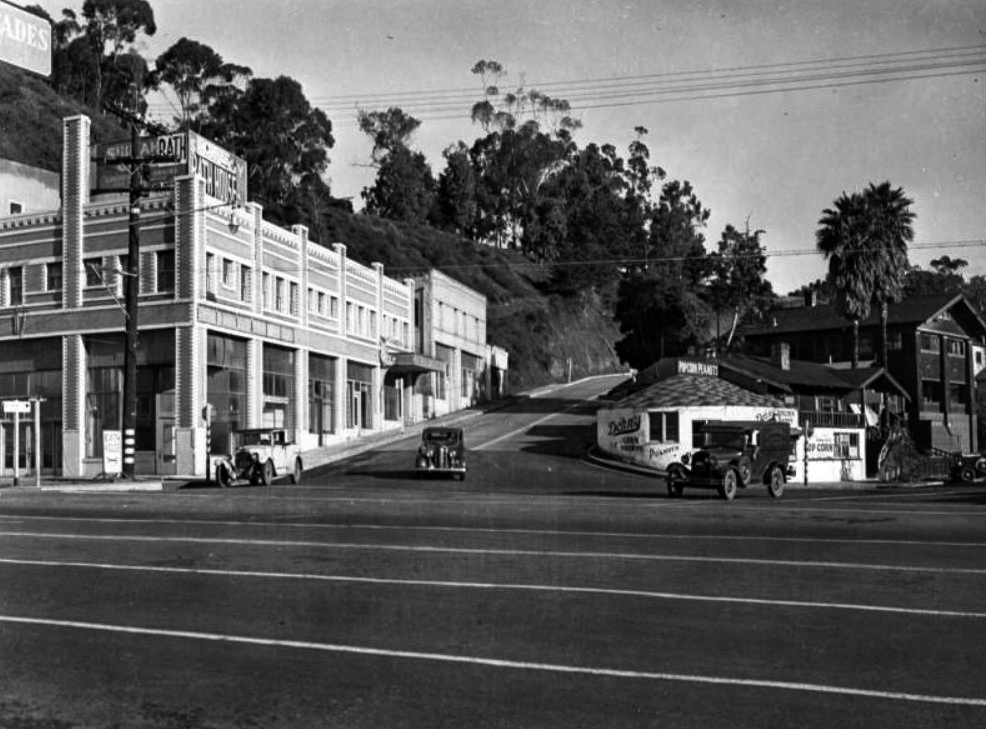

| (1930s)^** - Intersection of Pacific Coast Highway, Chautauqua Blvd. and Channel Road, Santa Monica. |

|

|

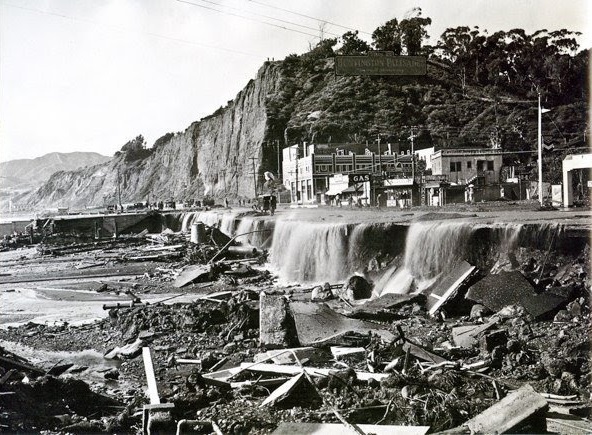

| (1938)^^^^ - View of the Santa Monica Canyon flood of 1938. The sign on top of the hill reads: HUNTINGTON PALISADES. |

Historical Notes In 1938, PCH was damaged by one of wettest seasons ever to hit Southern California. |

|

|

| (1938)#*#* – Repairing Pacific Coast Highway after the great storm of 1938. The intersection of PCH and Chautauqua Blvd is seen in the background. Photo Date: March 7, 1938 |

|

|

| (ca. 1945)** - Aerial view of the intersection of Chautauqua Boulevard, West Channel Road and Pacific Coast Highway. The Canyon Market Groceries and Liquor building is at center, and to the left is a billboard sign for the Lindomar Hotel. In the left foreground Pacific Coast Highway separates the market from a partly filled parking lot and the beach. The area where the market is located appears to be cut out of the solid rock hill in the background. |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)^** - View showing automobile traffic at the intersection of Pacific Coast Highway, Chautauqua Boulevard, and Channel Road in Santa Monica. Two boys are sitting on a railing watching traffic across from storefront signs that read "Canyon Market", "Canyon Liquor Store", and "Gloryfied frankfurters." |

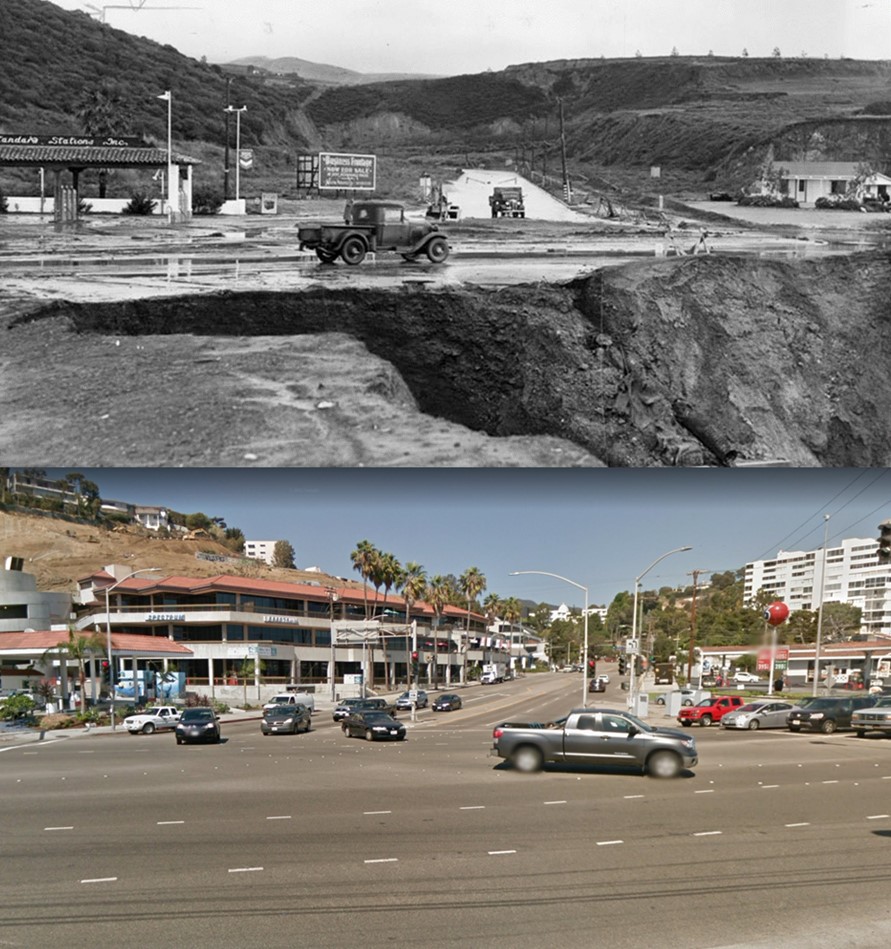

Then and Now

|

|

| (1930s vs 2022)* - Intersection of Pacific Coast Highway, Chautauqua Blvd. and Channel Road, Santa Monica. |

Sunset and PCH

|

|

| (1940)* – View looking NE showing Sunset Boulevard where it comes into Pacific Coast Highway (PCH), after a storm. In the foreground can be seen the erosion of a section of the highway. Photo taken from site of Gladstones today. |

Historical Notes This section of Pacific Coast Highway was formally dedicated as the 'Theodore Roosevelt Highway' when it was completed in 1929 and was generally known as the 'Roosevelt Highway' or 'Coast Highway' in the 1930s. It was designated as US 101A (Alternate) in 1936. State legislative action in 1964 changed many highway numbers in California, and US 101A became CA 1. In the same year, the state legislature offically named CA 1 'Pacific Coast Highway' in Orange, Los Angeles and Ventura Counties.* Gas station on left is still there. Got remodeled 15- 20 years ago. Click HERE for contemporary view. |

|

|

| (1960s)* - Sunset Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway. |

Historical Notes The Standard Oil Station pictured was owned by Clint Eastwood's father. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1940 vs. 2022)* – Looking NE on Sunset Boulevard from PCH showing how the area has evolved over the last 80 years. Current image taken from driveway of Gladstones. |

* * * * * |

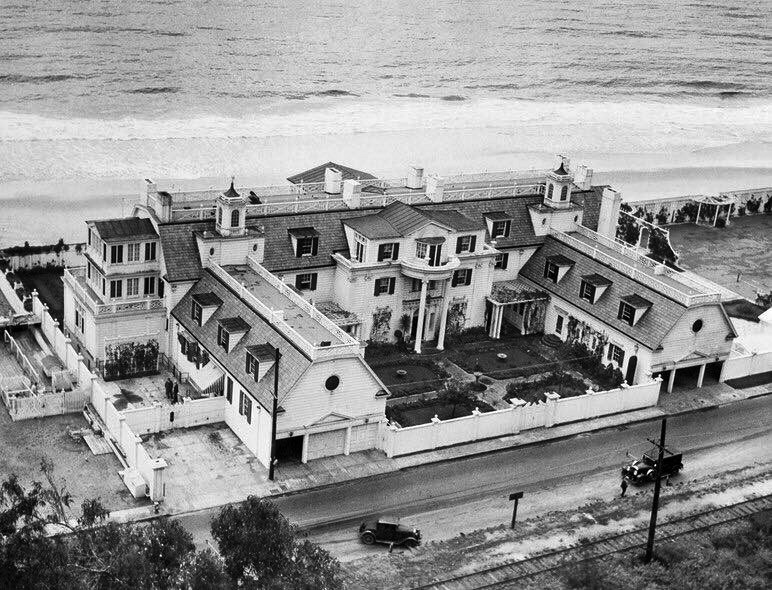

Marion Davies Mansion

|

|

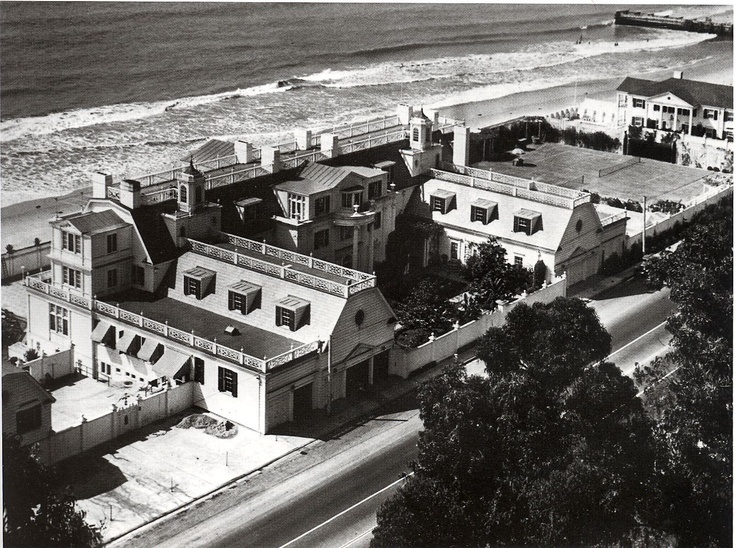

| (ca. 1929)* - View of Santa Monica homes along Pacific Coast Highway, looking south. The highway is in the foreground at center and follows the contours of the coast as it disappears into the distance at center. The right side of the road is lined with an assortment of large beach houses including Marion Davies' mansion (center-right) which is still under construction. On the left side of the highway, a railroad runs parallel to the road and the steep cliffs of Palisades Park rise above the tracks. There are trees along the top and bottom of the cliffs, but the faces are bare rock. There is a small wharf at center that sticks out above the low tide, and a long pier is visible in the background at right. |

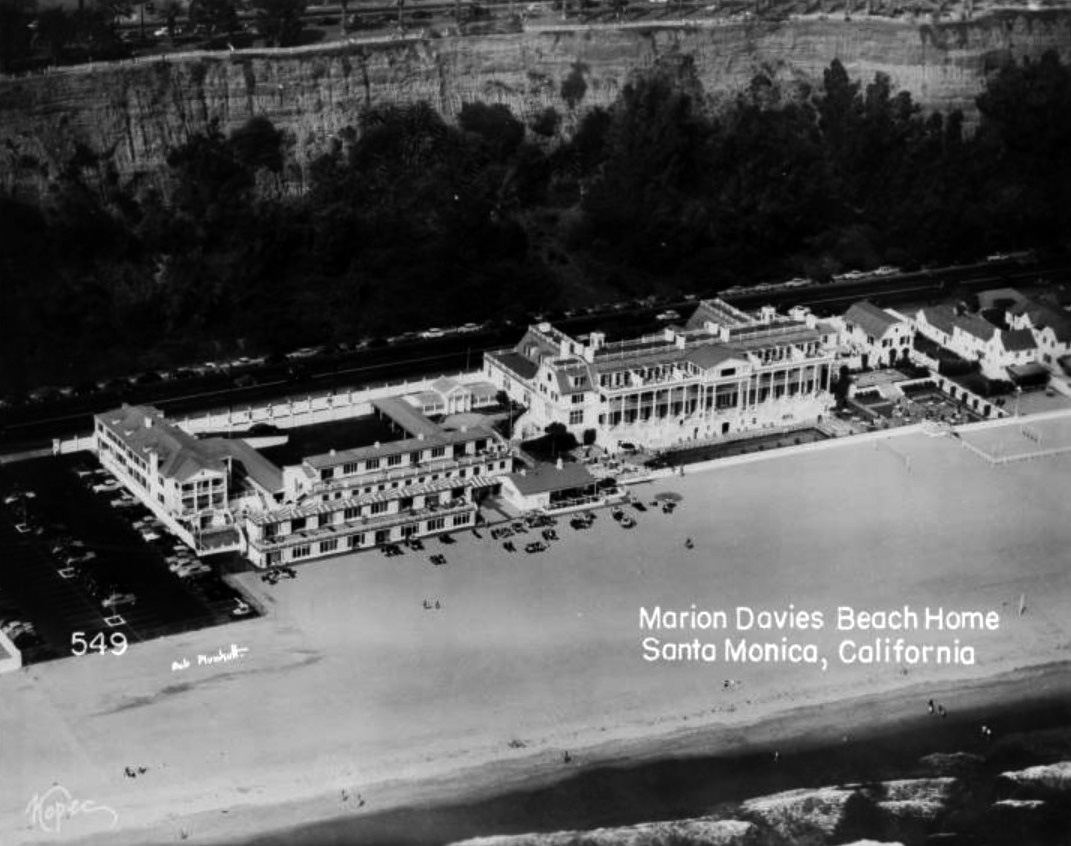

Historical Notes William Randolph Hearst might have been the first media mogul of the 20th Century. In his day, Hearst owned 28 major newspapers and 18 magazines, as well as radio stations and movie companies. Santa Monica’s Gold Coast was so desirable that in the 1920s, Hearst, one of the richest and most powerful men in America, bought 4.91 acres of beachfront property so that he could build a mansion for his mistress, actress Marion Davies. |

|

Historical Notes During the 1930s and 1940s, Marion Davies' Beach House in Santa Monica became the epicenter of Hollywood's social scene, solidifying its place in entertainment history. Davies and William Randolph Hearst frequently hosted lavish parties and exclusive film screenings for the entertainment elite, making the estate a must-visit destination for celebrities and industry moguls. The property was a crown jewel of Santa Monica's prestigious "Gold Coast," a stretch of beachfront where numerous movie stars and influential figures owned homes. With its opulent design and extravagant amenities, the Beach House was widely regarded as one of the most lavish properties in the area, rivaling other famous residences of the time and cementing its status as a symbol of Hollywood's Golden Age glamour. |

|

|

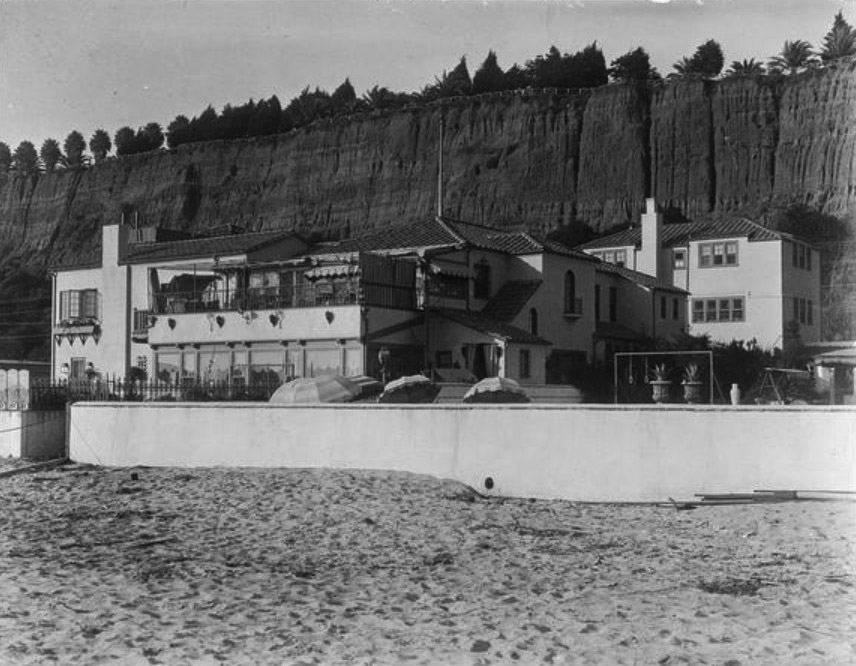

| (1978)* – View from the bluff looking down at the beach, highlighting changes to the Marion Davies residence over a 50-year span. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes After Marion Davies sold the estate in 1947 for $600,000, the property underwent significant changes. It was initially operated as a luxury hotel and limited-membership beach club, catering to an exclusive clientele. However, in 1956, despite opposition from neighbors, the main mansion was demolished, marking the end of an era for the iconic residence. The state of California then purchased the property in 1960, setting the stage for its future as a public space. Today, the site is known as the Annenberg Community Beach House, with only the original guest house and main pool surviving from Davies' time. |

Before and After

|

|

| (1929 vs. 1978)* – View looking south from Palisades Park toward the Santa Monica Pier. The most noticeable change over this nearly 50-year span is the widened beach, primarily the result of human intervention through beach nourishment projects. Also note the streetcar running along the Southern Pacific tracks on the Roosevelt Highway (now PCH) in the earlier image. |

Historical Notes The increased sand on Santa Monica Beach compared to 100 years ago is largely due to human intervention, particularly through beach nourishment projects. Over the past century, efforts have been made to widen and enhance the beach to boost tourism and recreation. Key factors include the artificial widening of the beach by adding approximately 30 million cubic yards of sand, sourced from infrastructure projects and dredging operations, and the desire to make Santa Monica Beach resemble wider, flatter East Coast beaches. In 1947, for example, nearly 14 million cubic yards of sand were removed to make way for El Segundo's Hyperion power plant. They were deposited onto Santa Monica's beaches. Another million cubic yards came a couple years later, the sand this time recovered from dredging operations along a nearby breakwater. In all, some thirty million cubic yards of sand have been dumped onto the beaches of Santa Monica and Venice. |

|

Historical Notes The railroad tracks will be removed in 1934 when Roosevelt Highway is widened to 4 lanes. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)* - View from the bluffs of Palisades Park, showing railroad tracks and the Roosevelt Highway (later Pacific Coast Highway) below, with the Santa Monica Pier and Ocean Park Pier in the distance. The mansion of actress Marion Davies is visible at center, with the new guest house still under construction at lower center-right. By 1934, the railroad tracks were removed, and Roosevelt Highway was widened. |

Historical Notes The site of the former Marion Davies estate on Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica is now home to the Annenberg Community Beach House. The original property, designed by architect Julia Morgan for William Randolph Hearst and actress Marion Davies, featured a grand 110-room mansion known as "Ocean House" or "The Beach House." This luxurious retreat was popular among Hollywood celebrities in the 1920s and 1930s. Although the main mansion was demolished in the 1950s, the guest house and original swimming pool were preserved and are now part of the Annenberg Community Beach House, which serves as a public recreational facility. |

|

|

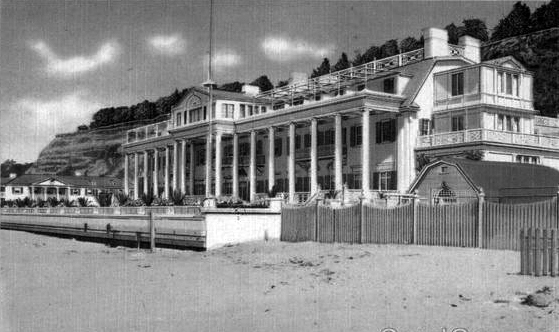

| (ca. 1931)* - View of Marion Davies’ 110-room mansion on Santa Monica beach designed by architect Julia Morgan and built circa 1926. The guest house closest to the camera still exists. Roosevelt Highway would be widened in 1934. |

Historical Notes William Randolph Hearst commissioned William Edward Flannery to construct a grand beach house for his longtime companion, actress Marion Davies. In 1926, architect Julia Morgan (the architect of Hearst Castle) was hired to complete the design and oversee construction of the estate, which featured an ornate swimming pool, several houses, gardens and an opulent 110-room mansion. The beach house served as Davies’ primary residence from 1929 to 1942. |

|

|

| (ca. 1933)* – Close-up front view showing the Marion Davies mansion. Two cars are parked across the highway next to the tracks. Roosevelt Highway would be widened in 1934. |

|

|

| (1934)* – Postcard view showing the “Beach Homes of the Motion Picture Stars” with Marion Davies’ house at lower right. |

Historical Notes Photo was taken shorty after railroad tracks were removed and Roosevelt Highway widened (1934). |

|

|

| (late 1930s)* - Closer view of Marion Davies' beach house (mansion) on the Pacific Coast Highway, Santa Monica |

Historical Notes Julia Morgan created a three-story, 34-bedroom Georgian mansion on the Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica. Called "Ocean House" or "The Beach House," it was the grandest property in the neighborhood. Rumor has it the cost was $7 million dollars. |

|

|

| (late 1930s)* - Aerial view showing the 4.91-acre Marion Davies estate in Santa Monica, designed by Julia Morgan. The building on the left is the guest house. |

Historical Notes Marion Davies was born Marion Douras in Brooklyn, New York on January 3rd, 1897. She always wanted to be a star. When she met William Randolph Hearst, she had already made a name for herself on the Broadway stage. Rumor has it she wrote her first film, "Runaway Romany," directed by her brother-in-law, George Lederer. 1918’s "Cecilia of the Pink Roses" was her first film backed by Hearst. Then her marketing campaign began. Over the next ten years, Davies filmed an average of almost three films a year. She was a tireless worker, always trying to live up to the relentless promotional campaigns launched by Hearst. In the early twenties, she and Hearst relocated their movie company, Cosmopolitan Productions, to California to join forces with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. Once the Beach House was finished, Marion evolved into Hollywood's premiere hostess. Her parties attracted the day’s biggest stars, international dignitaries and business titans. Those who knew Davies say she never took herself seriously and was beloved by all who knew her for her gracious spirit and charitable tendencies. |

|

|

| (1940s)* - Image of the mansion beach house of actress Marion Davies (which later became Ocean House, or the Oceanhouse Hotel, and Sand and Sea Beach Club), with the bluffs below Palisades Park visible in the background. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930s)* - Postcard view from the beach, showing the Marion Davies mansion. The Santa Monica bluffs are seen in the background. The mansion's guest house, on the left, still exists today. |

Historical Notes The three-story, 118-room, 34-bedroom, 55-bath Georgian mansion had 37 fireplaces, Tiffany chandeliers, a ballroom, a dining room from a Venetian palazzo, and a room that was coated in gold leaf. It was accompanied by three guesthouses, two swimming pools, tennis courts and dog kennels and was called “Ocean House." |

|

|

| (ca. 1930s)* - View showing guests enjoying a day by the pool at Marion Davies' mansion in Santa Monica. |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)* - Aerial view of Ocean House (or the Oceanhouse Hotel) and the Sand and Sea Beach Club on the property that was formerly the mansion of actress Marion Davies on the beach in Santa Monica, California, with Palisades Beach Road (part of Pacific Coast Highway) and the bluffs below Palisades Park in the background. |

Historical Notes In 1947, Davies sold the estate and it was converted into the Oceanhouse Hotel and Sand & Sea Beach Club. The main mansion was demolished in 1956, and the property was sold to the State of California in 1959. The Sand & Sea Club remained popular with regulars all the way through until the 1990s. In 2005, the Annenberg Foundation, at the recommendation of Wallis Annenberg, made a generous financial commitment to preserve the site for public use. The Annenberg Community Beach House at Santa Monica State Beach opened to the public on April 25, 2009, representing a unique partnership between the Annenberg Foundation, California State Parks and the City of Santa Monica. The total construction costs were roughly $30 million. |

|

|

| (2016)* - View of the restored Marion Davies Mansion pool, now part of the Annenberg Community Beach House. Photo by Mike Hope / Wikipedia |

Historical Notes The mansion's original pool was restored by the Annenberg Foundation and opened to the public on a fee for entry basis in 2009. The pool is trimmed in tile and has a marble deck. The mansion's original guest house also still exists and is used for events. New facilities include a pool house with changing areas and a second floor view deck, a new event house, a splash pad, gardens, beach volleyball/tennis courts, a children's play area, public restrooms, beach rentals, and a cafe. |

* * * * * |

Lasky Residence

|

|

| (1920s)* – Postcard view showing the beach home of Jesse Lasky (one of the founders of Paramount Pictures), located at 609 Ocean Front Walk across from the Sorrento/Gables. |

Historical Notes Filled with antiques and guests, the Lasky home became a magnet for stars, performers, and executives. From hosting lavish open air extravaganzas to spontaneous get-togethers, the beach house was where Hollywood culture maven Bess Lasky held court. |

|

|

| (1928)* – View showing the Jesse L. Lasky residence, with Spanish tile roof, large balcony, enclosed and open patios, umbrellas, and playground equipment, with beach and wall in foreground and cliffs in background. |

Historical Notes "'Our Santa Monica beach house, 609 Ocean Front, was a two-story hacienda surrounding a garden with a fountain. It originally had twelve guest suites...[which] my father enlarged..still further. We became a kind of hotel for the famous...I can remember no time when we were not inundated with house guests.” – Jesse L. Lasky, Jr. In 1930, Lasky traded Paramount shares and the beach house to Harry Warner for $250K. |

* * * * * |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)* - Roosevelt Highway, later renamed the Pacific Coast Highway (PCH), as seen from Palisades Park in Santa Monica. The highway runs parallel with the many beach clubs, restaurants, and residences on the coast. In the distance are Pacific Palisades, where the landmark Lighthouse bathhouse is located, and the Santa Monica Mountains. |

Historical Notes The Hollywood set and the uber-rich were drawn to Santa Monica’s beach in the 1920s & 30s. The opulent residences they constructed north of the Pier and fabulous parties they threw earned this stretch of sand the nickname of “Gold Coast”. Many other Hollywood stars, producers and movie studio moguls also built homes on Santa Monica's beach in the 1920s. Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford were among the first to make the move. |

|

|

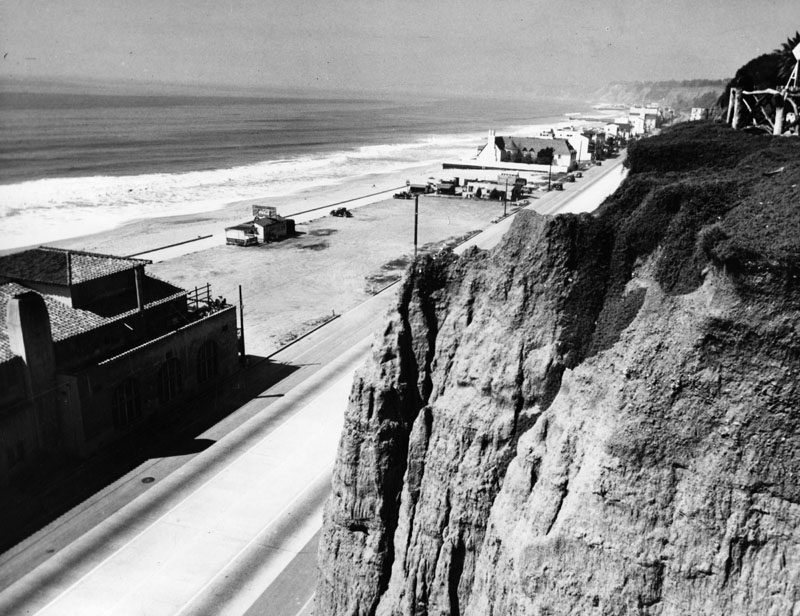

| (1931)* - Looking down upon the Roosevelt Highway (later Pacific Coast Highway) and crowds at the beach from the cliffs in Pacific Palisades. |

|

|

| (1934)* - Caption reads: A new link in the Roosevelt highway and an improved coastal boulevard which replaces the old narrow road along the beach at the foot of the Santa Monica Palisades, will be formally opened and dedicated on Monday afternoon. Governor F. F. Merriam and state, county and municipal officials will join in ceremonies which will climax months of work. Photo shows the highway link, which has been widened to 80 feet and extends nearly one mile. Arrow shows where boulevard rises to connect with Wilshire Boulevard on Ocean Avenue. |

* * * * * |

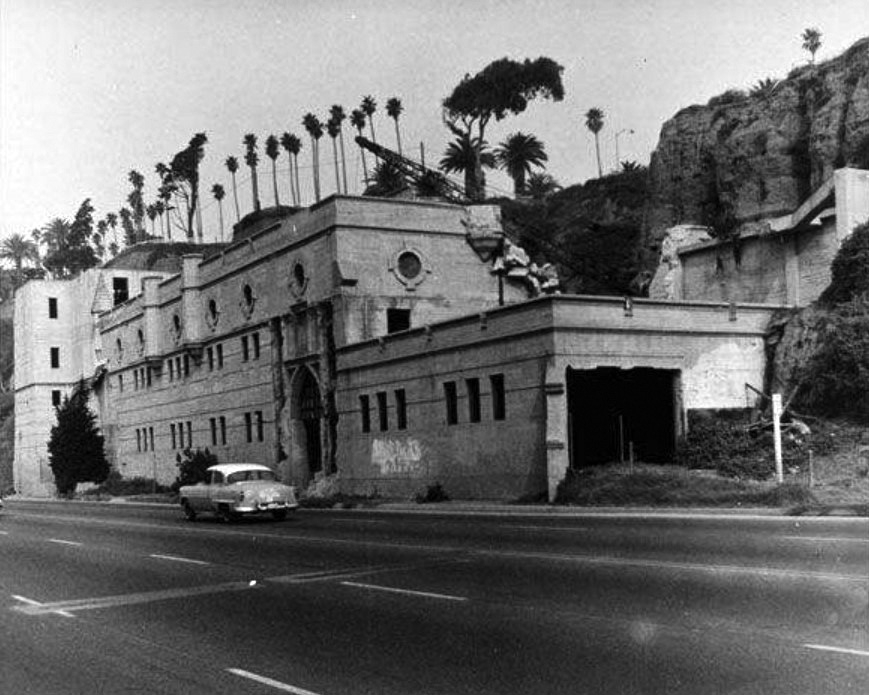

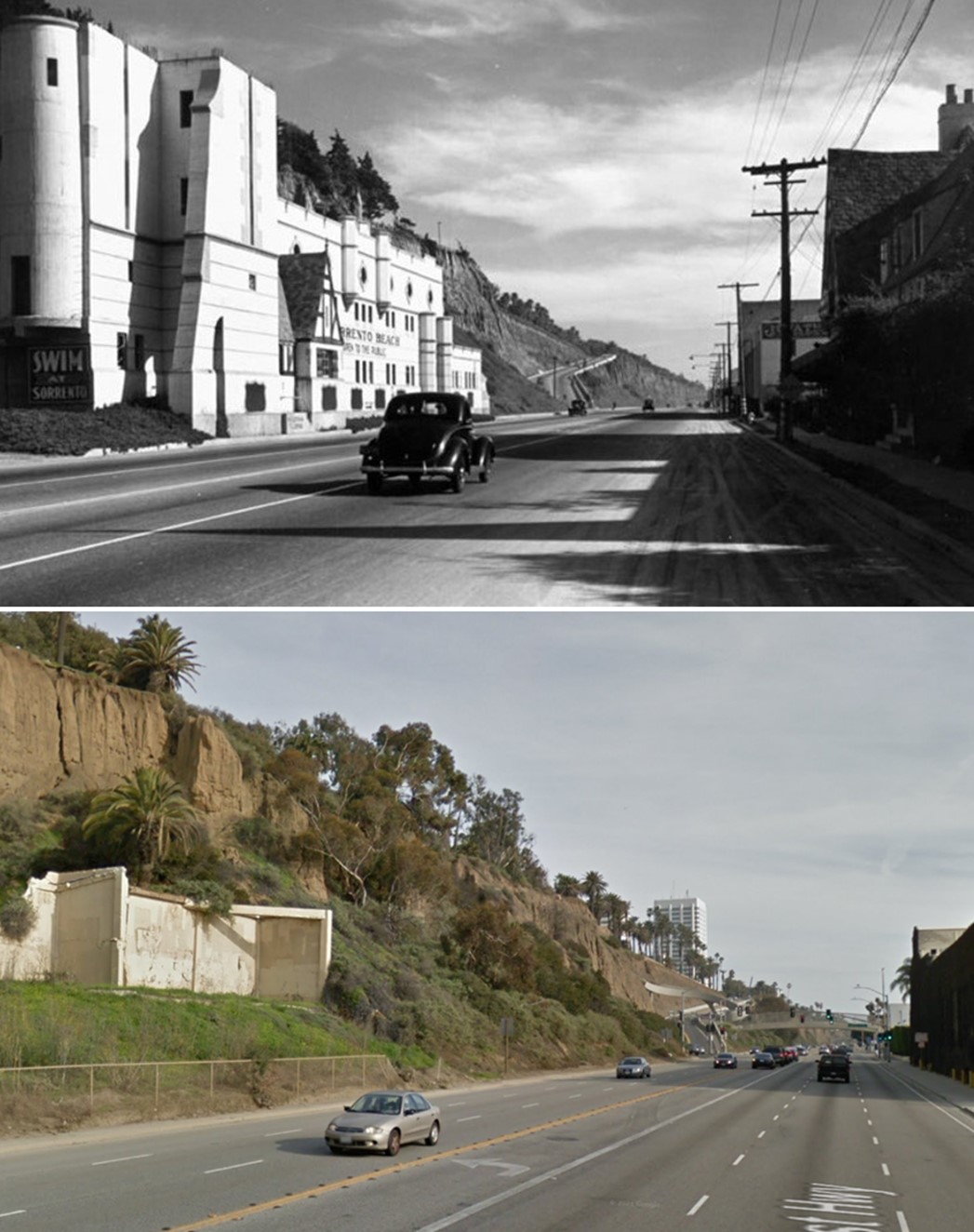

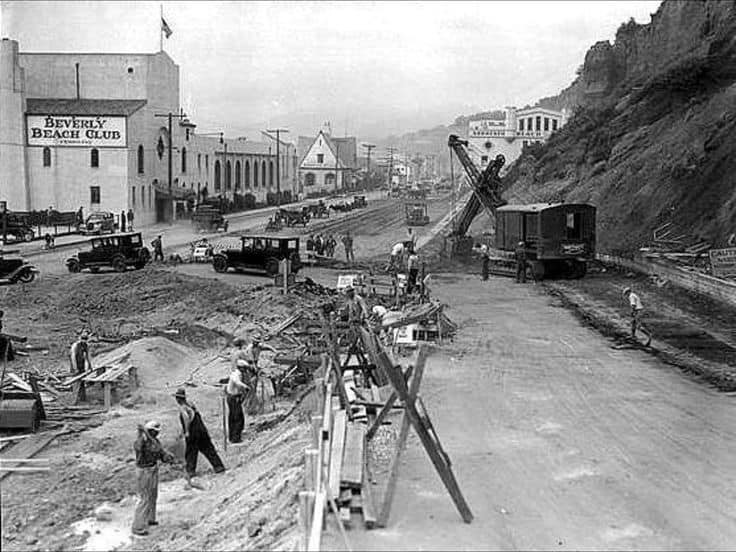

Sorrento Club Garage (later known as the Sorrento Ruins)

|

|

| (1936)* - View showing a car travelling south on Roosevelt Highway (later PCH) in Santa Monica with the Sorrento Beach Club garage on the left and the California Incline in the distance. |

Historical Notes IIn the 1920s, “Promoters decided to create a fantastic club (Gables Beach Club) and hotel complex on the cliffs at the foot of Montana Avenue...Designed to emulate the grandest castle-like structures of Europe.....would be twenty-one stories high and would include the first new bridge to span the beach road." - (from the book) Santa Monica Beach by Ernest Marquez |

|

|

| (1936)* - View showing a car travelling south on Roosevelt Highway (later PCH) in Santa Monica with the Sorrento Beach Club garage on the left and the California Incline in the distance. Photo by 'Dick' Whittington; Image enhanced and colorized by Richard Holoff |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)^ – Panoramic view towards the Palisades bluffs, showing the ruins of the Sorrento Club parking structure with another parking lot visible in the foreground. |

Historical Notes Originally designed to be 21 storys tall, only three stories were completed (1928) when the Great Depression hit. The smaller building would be used as a garage for Gables Beach Club across the street until a fire partially destroyed the club (1930). Within two years the club was rebuilt and reopened as the Sorrento Beach Club and the 3-story building continued to be used as a parking garage until 1962. Click HERE to see a postcard illustration of the proposed 21-story Gables Hotel. |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)^ – Panoramic view towards the Palisades bluffs, showing the ruins of the Sorrento Club parking structure with another parking lot visible in the foreground.Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

|

|

| (ca. 1950)* - Man standing at the edge of the Santa Monica Palisades bluffs looking down at the Sorrento Ruins. |

|

|

| (ca. 1952)* – View showing the ruins of the Gables Hotel, later Sorrento Club parking structure with the Palisades bluffs in the background. The structure was known as the Sorrento Ruins. Note the crane in the background. |

Historical Notes The Sorrento Ruins were left standing until the 1970s and then demolished. Today, part of the foundation is still visible and is being used as a retaining wall. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1936 vs. 2017)* - Looking south on PCH (CA-1) toward the California Incline showing the Sorrento Club and Ruins. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

* * * * * |

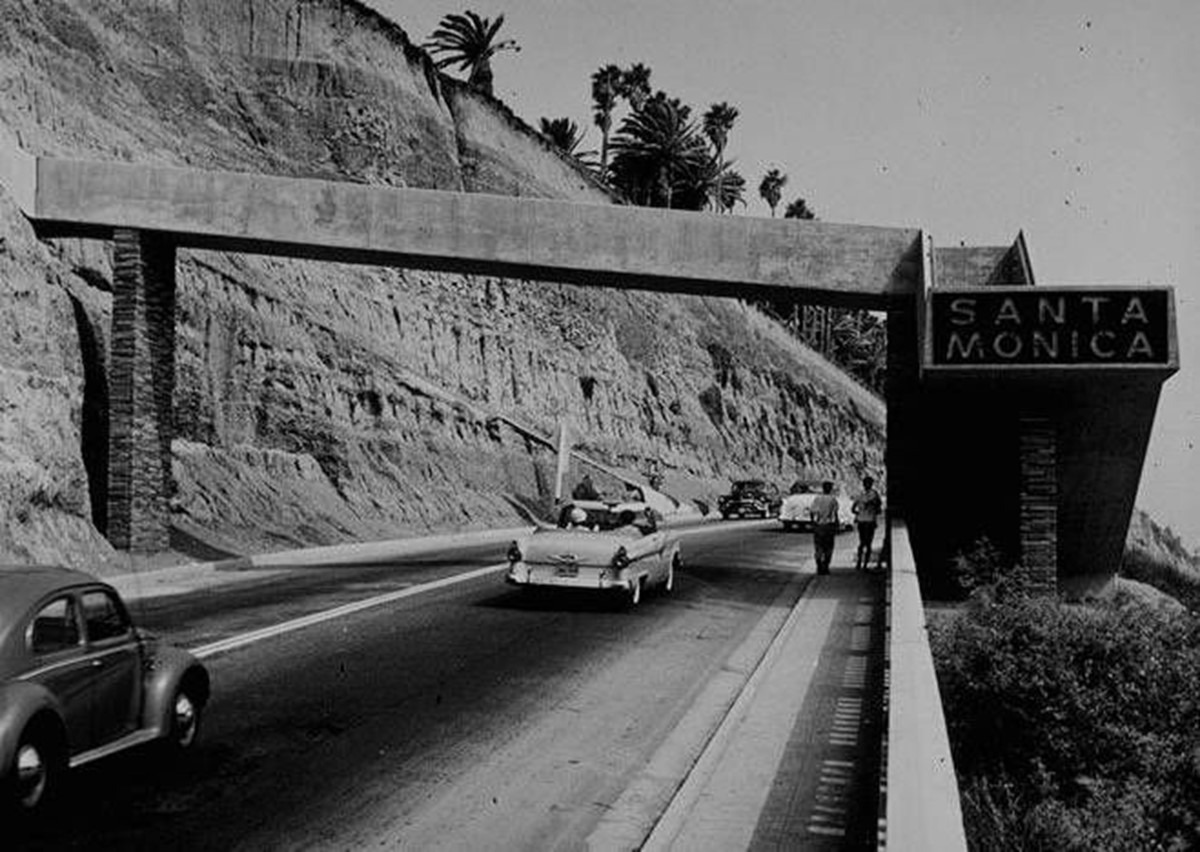

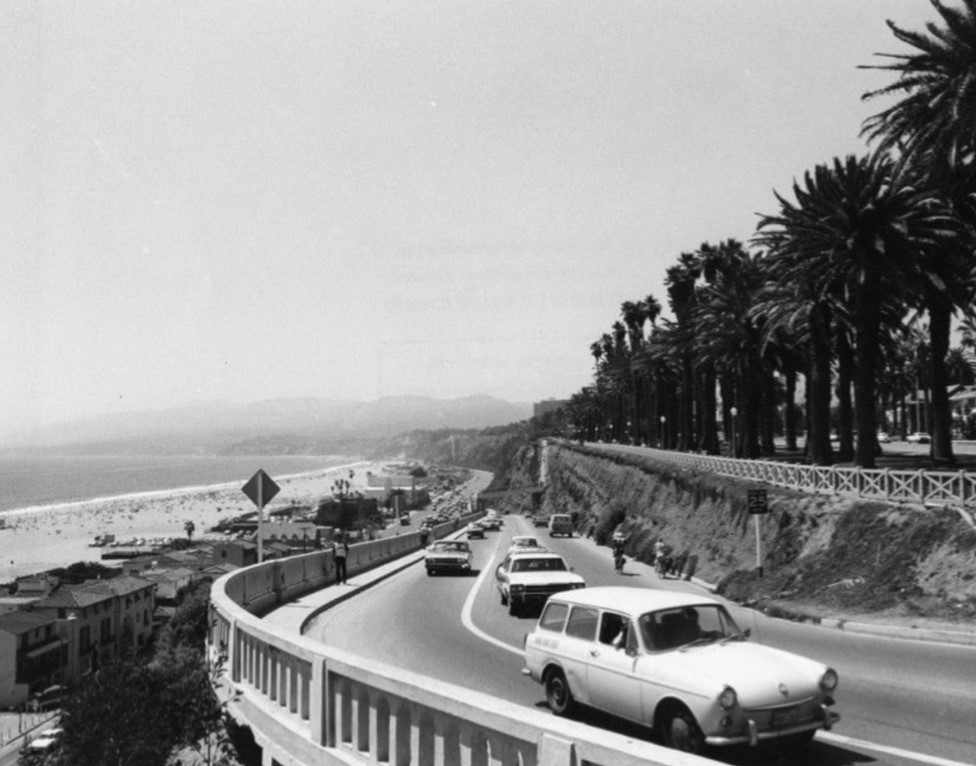

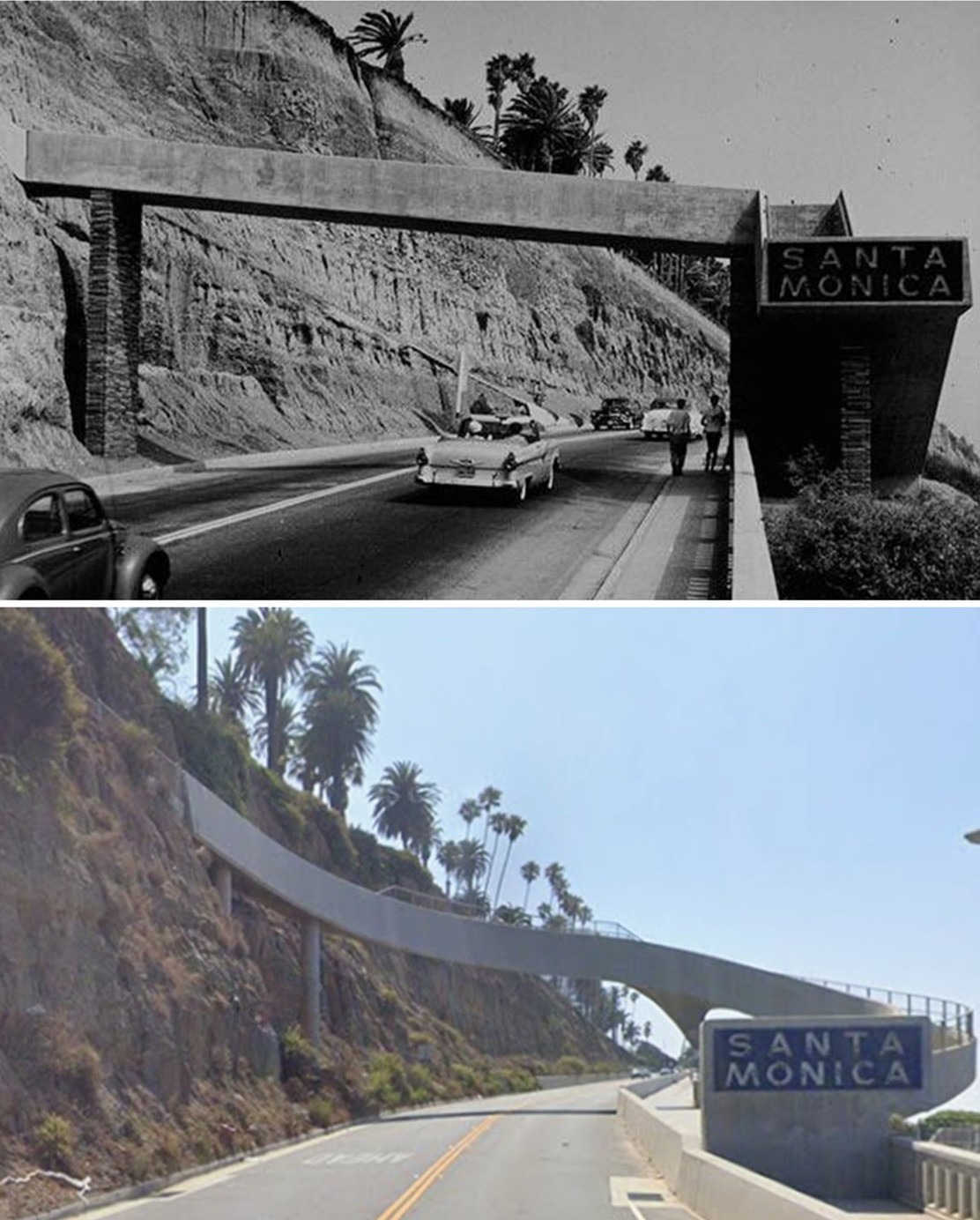

California Incline (1929 +)

|

|

| (ca. 1929)* - View of Santa Monica looking south from Palisades Park. In the foreground the slope of the California Incline cuts diagonally downhill; below lie beach houses, the bathing-area buildings and the shoreline. The Santa Monica Municipal Pier appears faintly in the distance. |

Historical Notes Before the Incline existed, beachgoers reached the shore by footpaths such as the Sunset Trail or stairways like the 99 Steps. Around 1905, a rough dirt road called Linda Vista Drive was carved into the bluffs, giving automobiles a shortcut to the beach. It was later paved and renamed the California Incline, taking its name from the street it connected with at the top—California Avenue. |

|

|

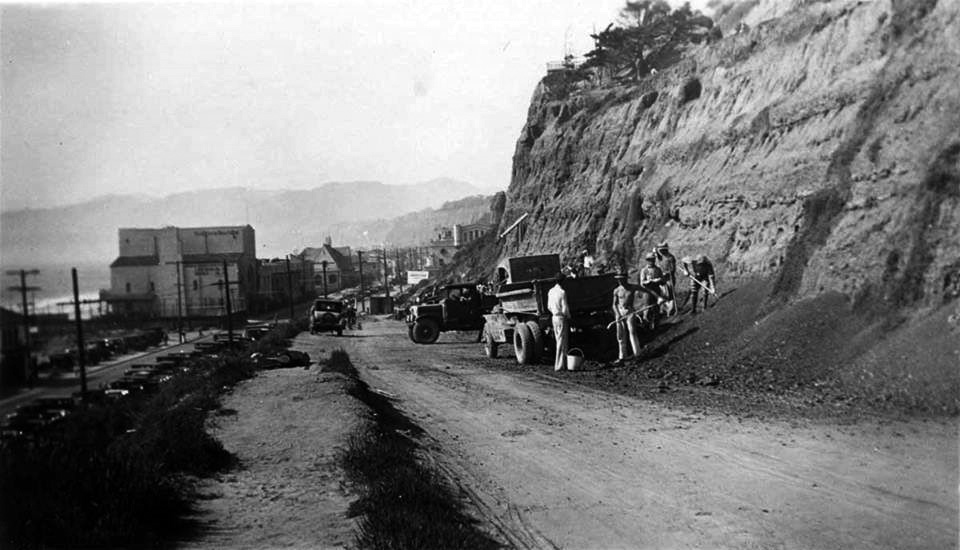

| (ca. 1929)* – Construction crews widening the Roosevelt Highway and the California Incline. |

Historical Notes During the late 1920s, the California Incline was widened and improved by the California Division of Highways as part of the coastal highway upgrade. Around the same time, the coast road was formally dedicated as the Theodore Roosevelt Highway, later known as the Pacific Coast Highway. These improvements modernized the Incline, doubling its width and turning it into a vital link between the expanding beach route and the city above. |

|

|

| (ca. 1929)* – Work crews widening the California Incline to improve automobile access from the bluffs to the beach road below. |

Historical Notes The widening of the Incline required reinforcing the soft sandstone cliffs that supported the road. Concrete retaining walls and surfacing were added to handle the growing number of vehicles using the route. The project transformed a narrow cliffside path into one of Santa Monica’s signature automobile approaches, reflecting the city’s rapid embrace of the motor age. |

|

|

| (1930s)* - View looking north along the concrete California Incline, with early automobiles heading between the beach and Ocean Avenue. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes By the 1930s, the California Incline was a fully paved concrete roadway carrying steady traffic between the Pacific Coast Highway and the bluff-top neighborhoods. The half-mile incline connected the growing coastal highway system to downtown Santa Monica and Palisades Park, making it an essential route for both residents and visitors. |

|

|

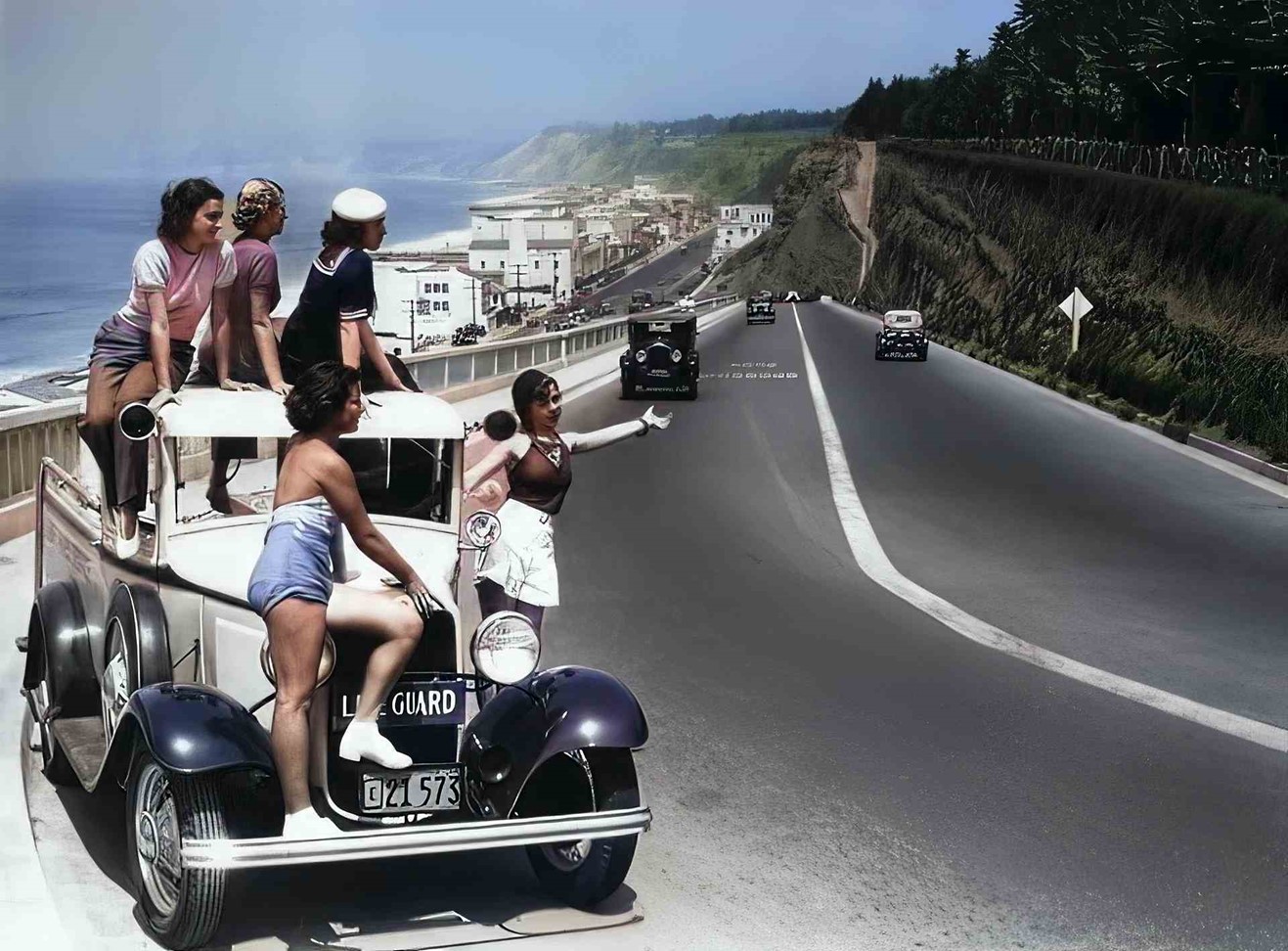

| (1930s)* - Five women ride in an open-bed lifeguard truck atop the California Incline, with the beach visible below. |

Historical Notes Scenes like this captured the spirit of the California Incline in its early decades—a place of sun, leisure, and local pride. The Incline linked Santa Monica’s beach life with its civic center, and became part of the city’s identity as a hub of recreation, lifeguard services, and coastal culture. |

|

|

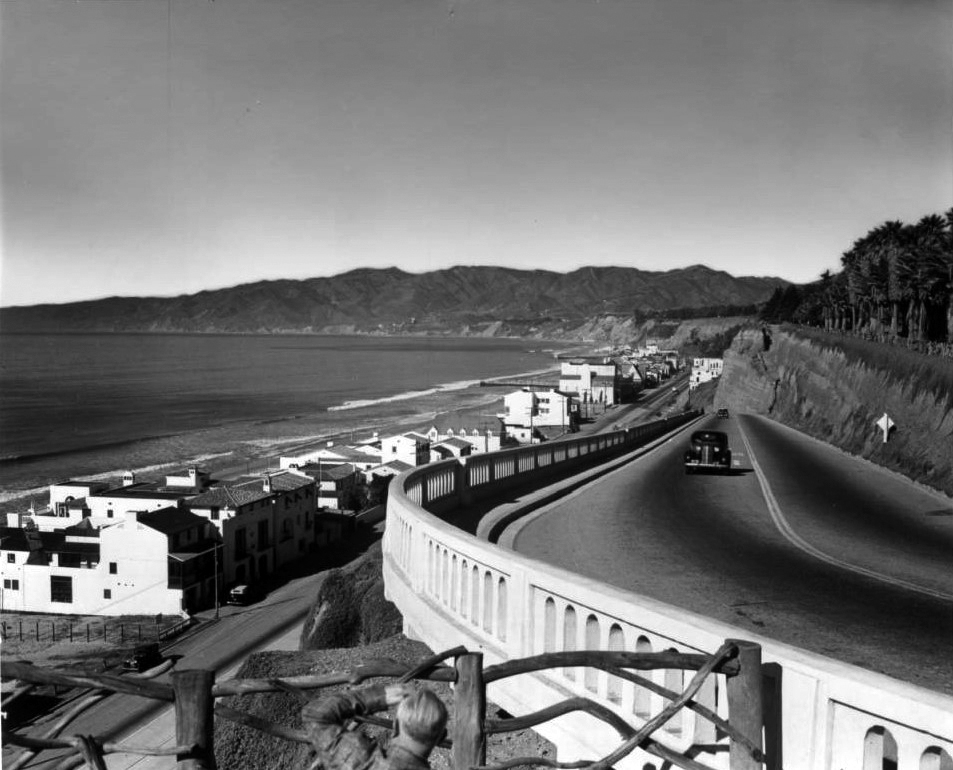

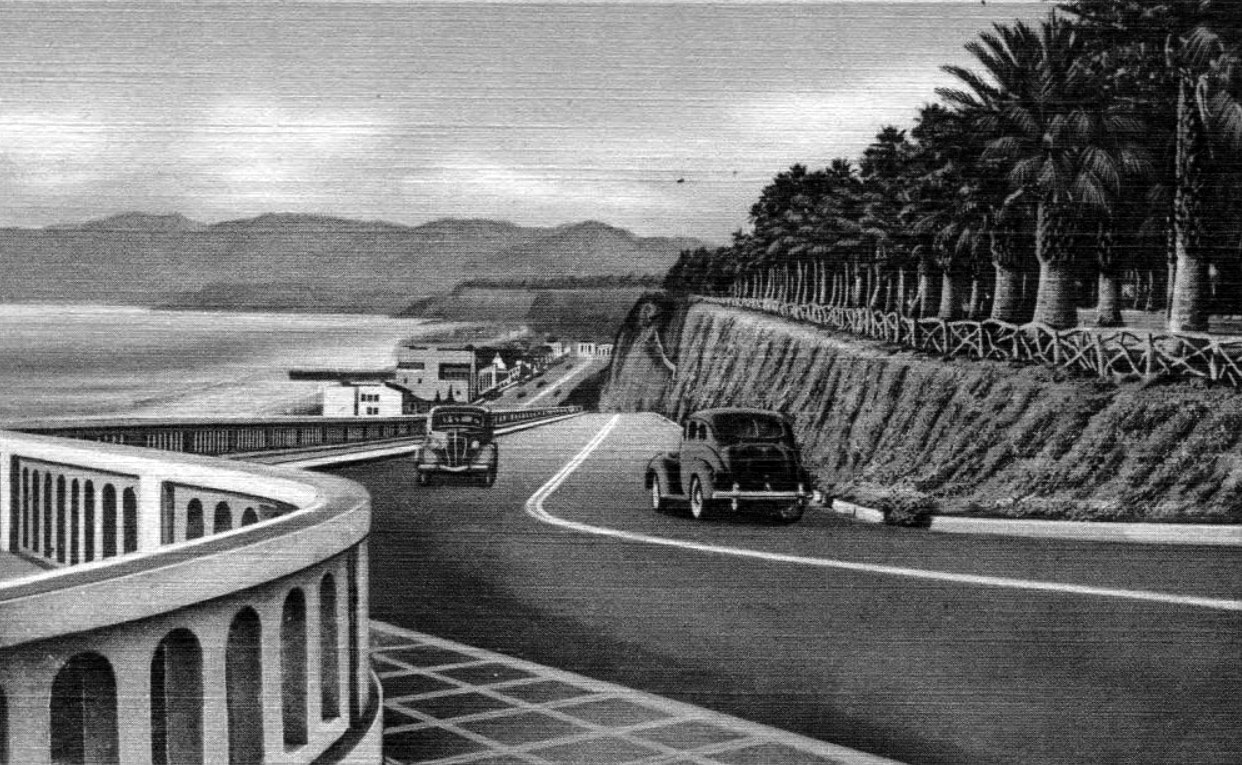

| (1930s)* - California Incline, Santa Monica (AI image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff). |

Historical Notes By this era, the Incline’s concrete balustrades and graceful curve down the bluff had become instantly recognizable. Its design reflected both function and beauty—a practical link to the beach and a scenic drive that framed sweeping ocean views. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)* – A man looks down toward the Santa Monica coastline from the top of the California Incline. Photo by Dick Whittington. |

Historical Notes This quiet moment from the late 1930s shows the Incline’s dual purpose—as a transportation route and as a scenic overlook. From the top of the bluff, Palisades Park offered panoramic views of the ocean, while the Incline provided a graceful descent to the beach and the Pacific Coast Highway below. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)* – Postcard view showing cars traveling up and down the California Incline, which runs between Ocean Avenue and Pacific Coast Highway. Palisades Park is on the right. |

Historical Notes Color postcards of this era often featured the Incline as a symbol of Santa Monica’s charm. The curving roadway, palm-lined park, and beach below captured the harmony between urban design and the natural coastline. The Incline was widely regarded as one of the most scenic gateways in Southern California. |

|

|

| (1949)* – Looking south from Palisades Park, this view takes in the California Incline, the Santa Monica Municipal Pier and Yacht Harbor, and the Ocean Park Pier. Photo from the Eric Weinberg Collection. |

Historical Notes By the post-war years, the Incline had become a fixture of Santa Monica’s beach culture, linking the bluff-top city streets to the busy piers and amusement zones below. The Santa Monica Municipal Pier and the adjacent Yacht Harbor were central gathering places for fishing, boating, and entertainment—easily reached by way of the California Incline. |

|

|

| (1940s)* - Postcard view showing the California Incline road with automobiles, leading down from bluffs and Palisades Park down to Pacific Coast Highway. Beach houses, the Santa Monica Pier with the La Monica Ballroom at its center, and other buildings are also in this view, with Ocean Park amusement piers in the distance. |

Historical Notes During the 1940s, the beach and pier area flourished with dance halls, restaurants, and small cottages along the shore. The California Incline served as the main link between downtown Santa Monica and the thriving beachfront, making it one of the most photographed stretches of roadway on the coast. |

|

|

| (1957)* - Heading up the California Incline toward the pedestrian over-crossing that connects Palisades Park atop the bluff to the bridge across the Pacific Coast Highway below. |

Historical Notes In 1957, Santa Monica built its first dedicated pedestrian bridge across the California Incline to improve safety for beachgoers and residents. Before this bridge, pedestrians had to share the roadway or descend steep stairways cut into the bluffs. The new overcrossing, officially known as the Idaho Avenue Pedestrian Overcrossing, linked Palisades Park and Ocean Avenue at the top with a stairway and walkway leading to the beach and Pacific Coast Highway below. Constructed of reinforced concrete with steel railings, it reflected the city’s postwar commitment to both recreation and public safety as beach traffic and tourism surged. |

|

|

| (1959)* – A woman walks down the California Incline toward the Pacific Coast Highway and the beach below. |

Historical Notes This image reflects a quieter side of the Incline, showing it as part of everyday life for locals as well as tourists. For generations of residents, walking the Incline became a ritual—offering sea air, exercise, and one of the best views in town. |

|

|

| (1972)* - Looking north along the Palisades bluffs from the California Avenue Incline Bridge, connecting Ocean Avenue to the Pacific Coast Highway. |

Historical Notes By the 1970s, the road was officially known as the California Avenue Incline Bridge. It remained a vital connector but was beginning to show its age after decades of coastal erosion and increasing vehicle loads. Plans for eventual reconstruction were already being discussed by city engineers. |

|

|

| (2013)* - Two men walk up the California Incline using the roadway instead of the narrow sidewalk. Photo by “Tinton5.”/ Wikipedia |

Historical Notes By the early 1990s, engineers had determined that the original Incline bridge no longer met modern seismic standards. Funding for its replacement was secured in 2007, but construction did not begin until 2015. This photo shows the old roadway shortly before demolition, capturing the familiar curve that had carried cars and pedestrians for more than a century. |

.jpg) |

|

| (2020)* – California Incline after its full reconstruction, featuring lanes for cars, cyclists, and pedestrians, along with two new bridges linking Palisades Park and the beach. Photo courtesy of Steve Loeper / Santa Monica Conservancy. |

Historical Notes Reopened with much celebration in 2016, the rebuilt California Incline was engineered to current seismic standards while preserving its classic appearance. The new structure is supported by deep concrete pilings and stabilized with more than a thousand soil anchors. Today the Incline serves as a multi-modal route—welcoming vehicles, cyclists, and walkers—and remains one of Santa Monica’s most iconic coastal landmarks. Click HERE to see more Early Views of the California Incline (1905+). |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1957 vs. 2025)* – Looking up the California Incline toward the pedestrian crossing that connects the Palisades Park at the top to the bridge crossing Pacific Coast Highway. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes The original Idaho Avenue Pedestrian Overcrossing, completed in 1957, was a simple straight-span bridge of reinforced concrete with steel railings. Its narrow, utilitarian design reflected mid-century engineering priorities—function over form—yet it quickly became a familiar part of the California Incline’s profile. The bridge provided a safe connection between Palisades Park and the beach below, allowing pedestrians to cross over the busy Pacific Coast Highway without navigating the steep bluffs or the traffic on the Incline itself. The replacement bridge, completed in 2016 as part of the California Incline reconstruction, introduced a more graceful, curved design that follows the contour of the bluff. Built to modern seismic and accessibility standards, it features a wider deck, integrated lighting, and protective railings. The new bridge not only enhances safety but also complements the scenic setting, offering a visual echo of the Incline’s sweeping arc and framing panoramic ocean views from both directions. |

* * * * * |

McClure Tunnel (originally Olympic Tunnel)

|

|

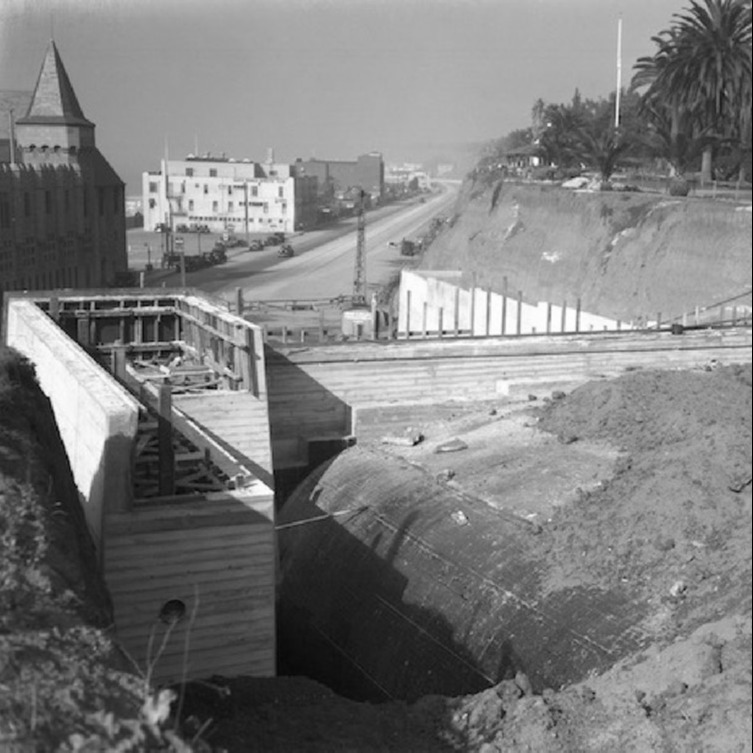

| (1934)* – View showing the construction of the Olympic Tunnel (renamed the McClure Tunnel in 1969). |

Historical Notes The tunnel was conceived as a vital connection between Roosevelt Highway (later Pacific Coast Highway) and Colorado Avenue/Olympic Boulevard, leading to Lincoln Boulevard and Los Angeles beyond. At the time, Santa Monica was experiencing rapid growth in both automobile and rail traffic. The corridor served both modes—the auto tunnel for cars and Pacific Electric streetcars on tracks along the bluffs above—capturing a transition era as Southern California shifted from electric rail to the automobile. This early phase in 1934 shows the foundations of a project that would soon become a signature entryway to Santa Monica’s beaches. |

|

|

| (1935)* - Workers stand on the arched roof of the new Colorado Avenue and Ocean Avenue tunnel (then called the Olympic Tunnel, later renamed the McClure Tunnel). Pacific Electric tracks run in the foreground, while the Looff Hippodrome carousel building and La Monica Ballroom rise along the pier behind them. Signs advertise auto parks, cafes, and apartments catering to the growing beachfront crowds. |

Historical Notes This 1935 view shows construction of the Colorado Avenue and Ocean Avenue tunnel in Santa Monica, with its arched top taking shape. Pacific Electric streetcar tracks run across the foreground, while in the distance the Santa Monica Pier, Yacht Harbor, and breakwater are visible. Signs for local businesses such as “Whirlwind Auto Park,” “Albers Waffle Parlor,” and the “Overlook Hotel and Apartments” capture the commercial life of the era. The Looff Hippodrome with its dome and the La Monica Ballroom also appear, anchoring the scene in the city’s beachfront culture. The Pacific Electric tracks seen here once carried passengers and freight into Santa Monica, but service declined after World War II as car travel grew. Passenger service ended in 1953, and the tracks above the tunnel were removed in the 1960s when the Santa Monica Freeway was extended to the coast and the tunnel was rebuilt for automobiles. Today, part of that old route has been revived by Metro’s E Line, which opened in 2016 and once again brings rail passengers to downtown Santa Monica near the pier. |

|

|

| (1935)* - Construction of the Roosevelt Highway Tunnel (Olympic Tunnel) under Ocean Avenue. One of the towers of the Deauville Club can be seen on the left. Photo date: December 2, 1935 |

Historical Notes By late 1935, construction on the Roosevelt Highway Tunnel was in full swing. The project required cutting beneath Ocean Avenue to link the new Roosevelt Highway with downtown Santa Monica, a major engineering effort for its time. Visible in the background is one of the towers of the Deauville Club, a glamorous beach resort that symbolized Santa Monica’s popularity as both a local and tourist destination. The tunnel’s design used reinforced concrete with a flat-arch profile, allowing for four lanes of traffic and accommodating the Pacific Electric tracks that ran overhead. This stage of construction set the scene for the tunnel’s formal dedication just two months later, when Santa Monica would celebrate its newest gateway with a parade and motor cavalcade. |

|

|

| (1935)* - Construction of the Roosevelt Highway Tunnel under Ocean Avenue on December 2, 1935. |

Historical Notes This photo shows the Roosevelt Highway Tunnel (later called the Olympic Tunnel, and today the McClure Tunnel) in its final stages of construction beneath Ocean Avenue. Reinforced concrete walls and the arching roof were being finished to create a modern four-lane roadway. Above the tunnel, Pacific Electric streetcar tracks still ran along the bluff, a reminder of the rail network that once carried commuters and beachgoers between Santa Monica and Los Angeles. Taken just weeks before the tunnel’s February 1936 dedication, the image captures a pivotal moment when Santa Monica was re-engineering its landscape to balance cars, trains, and growing seaside crowds. |

|

|

| (1936)* – Ceremonies marking the opening of a 400-foot tunnel beneath Colorado and Ocean Avenues in Santa Monica on February 1, 1936. The tunnel, originally known as the Olympic Tunnel and later renamed McClure Tunnel, joins the Roosevelt Highway (later, Pacific Coast Highway) with Olympic and Lincoln boulevards. |

Historical Notes On opening day, February 1, 1936, the “Olympic Tunnel” was formally dedicated. The Los Angeles Times described the celebration: “Through tunnel to coast at Santa Monica went a cavalcade of autos when the ribbon was cut February 1st. Flat-arch construction and four traffic lanes are features.” Though plans for a parade and barbecue in the tunnel were canceled due to poor weather, the event still drew a large crowd eager to see the city’s newest civic achievement. The completion of the tunnel marked the beginning of a new era in Santa Monica’s transportation history, where automobiles and beach tourism would dominate, gradually pushing aside the Pacific Electric system that had once defined regional travel. |

|

|

| (1936)* – View showing hundreds of people at dedication of the new Santa Monica tunnel linking Roosevelt Highway with Olympic and Lincoln boulevards (Feb. 1, 1936). |

Historical Notes Known initially as the Olympic Tunnel, the structure became the McClure Tunnel in 1969, honoring Robert E. McClure, longtime editor of the Santa Monica Evening Outlook and an advocate for the freeway system. The tunnel linked Roosevelt Highway with Olympic and Lincoln Boulevards, providing a direct conduit between downtown Santa Monica and the coast. By the 1950s, Pacific Electric service had ended, and in the 1960s the tracks were removed as the Santa Monica Freeway was extended directly into the tunnel. The old streetcar right-of-way was erased, and the tunnel fully adapted for cars. Yet decades later, rail returned nearby with the opening of Metro’s E Line in 2016, once again delivering passengers to downtown Santa Monica just a few blocks from the pier. |

|

|

| (1936)* – View showing a new Ford V-8 Fordor sedan as it exits the tunnel in Santa Monica onto Olympic Boulevard, which leads to Lincoln Boulevard. The tunnel connected those streets with Roosevelt Highway. The above photo was published in the Feb. 23, 1936 Los Angeles Times automotive page. |

Historical Notes Automakers seized on the tunnel’s publicity value, using images like this to emphasize the freedom of modern motoring. In the background, the roofline of the Deauville Club looms, tying together Santa Monica’s glamorous beachfront reputation with its new transportation gateway. |

|

|

| (1936)* – Night view looking west toward the entrance to the new McClure Tunnel from the Olympic Boulevard side. Photo Date: May 22, 1936. |

Historical Notes A night view shows the tunnel freshly completed, lit from the Olympic side and framed by palm trees and streetlamps. The structure quickly became a recognizable landmark for motorists, symbolizing Santa Monica’s identity as both a beach city and a node in Los Angeles’ expanding freeway network. |

|

|

| (2022)* - Contemporary view of the eastern portal of the McClure Tunnel. |

Historical Notes Today, the McClure Tunnel serves as the transition point between the Santa Monica Freeway (I-10) and Pacific Coast Highway. While modern traffic has far surpassed the expectations of its 1930s designers, the tunnel endures as both a bottleneck and a symbolic passageway — guiding travelers from urban Los Angeles to the open Pacific coast. The story of the tunnel mirrors the region’s broader transportation history: from rail to freeway, and now back to rail nearby with the revival of passenger service through Metro’s E Line to Downtown Santa Monica (4th & Colorado). |

* * * * * |

Route 66

.jpg) |

(1936)^**^ - Postcard view of the Santa Monica Pier and Beach looking from Palisades Park. Route 66, End of the Trail sign at lower right.

|

Historical Notes In 1936, Route 66 was extended from downtown Los Angeles to Santa Monica, today the intersection of Olympic Boulevard and Lincoln Boulevard (a segment of State Route 1). Even though there is a plaque dedicating Route 66 as the Will Rogers Highway placed at the intersection of Ocean Boulevard and Santa Monica Boulevard, the highway never terminated there. Route 66 was unofficially named "The Will Rogers Highway" by the U.S. Highway 66 Association in 1952, although a sign along the road with that name appeared in the John Ford film, The Grapes of Wrath, which was released in 1940, twelve years before the association gave the road that name. A plaque dedicating the highway to Will Rogers is still located in Santa Monica (Ocean and Santa Monica Boulevards).*^ |

* * * * * |

Palisades Park

|

|

| (1937)* - Corner view of Palisades Park (right), shows the 297 foot drop-off onto the palisades. Parts of the Roosevelt Highway can be seen and the Santa Monica beach is in the background. |

Statue of Santa Monica

|

|

| (1937)* - View of the statue St. Monica for whom the city is named. The statue is located in Palisades Park in Santa Monica. Eugene Morahan is the sculptor. |

Historical Notes The 18-ft. high Art Deco Sculpture for whom Santa Monica was named was sculpted in 1934 by Eugene Morahan as a Public Works of Art project and presented to the citizens of Santa Monica by the Federal Government. Morahan and his wife (Grace) lived at the Tennis Club on Third Street in Santa Monica where the statue was caste in the backyard. It was to be installed during the celebration of Pioneer Day and as Morahan was under great pressure to complete his work by that deadline, he contacted his good friend and fellow sculptor, Gutzon Borglum to leave his work on Mount Rushmore and come down to help him finish his work on Saint Monica.+# |

.jpg) |

|

| (2007)*^ - Close-up view of the statue of Santa Monica by Eugene Morahan. Photo by Sharon Mollerus / Wikipedia |

Historical Notes The statue is located at the foot of Wilshire Boulevard just a block or so north of Santa Monica Boulevard. |

|

|

| (ca. 1940)#^# – Postcard view showing a couple enjoying a leisurely day in the shade of a palm tree at Palisades Park, Santa Monica. |

* * * * * |

|

|

| (1928)^*^* - View of intersection of Santa Monica Blvd. and Third Street facing northeast, with pedestrians crossing street, vehicles in foreground and background, businesses, and Santa Monica City Hall. Legible business signs include: The Florsheim Shoe, Santa Monica Radio Co., Jeweler Ellis, Security Trust & Savings Bank. A clock on the right reads 12:20. |

|

|

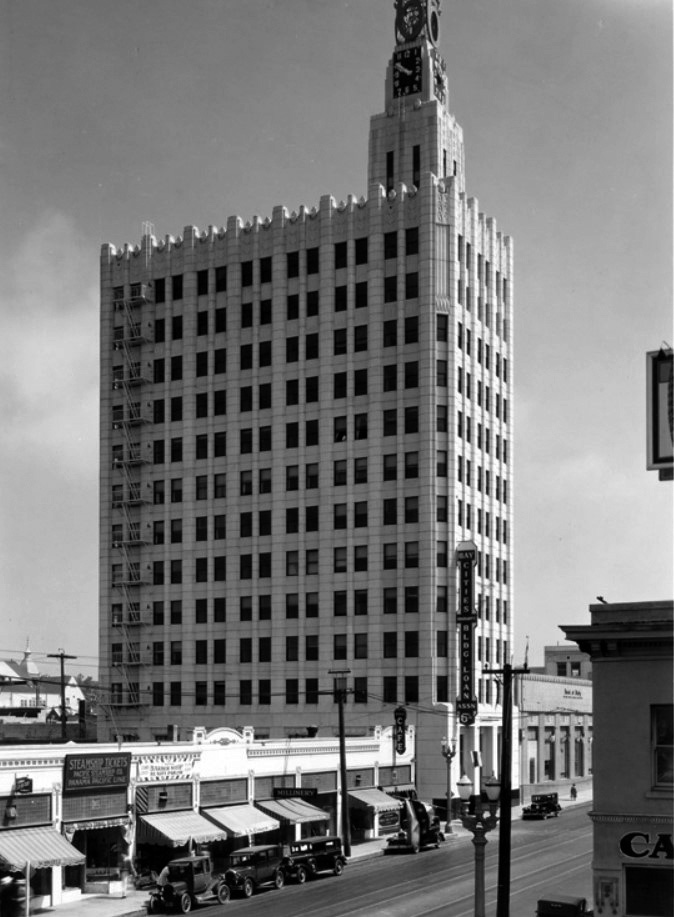

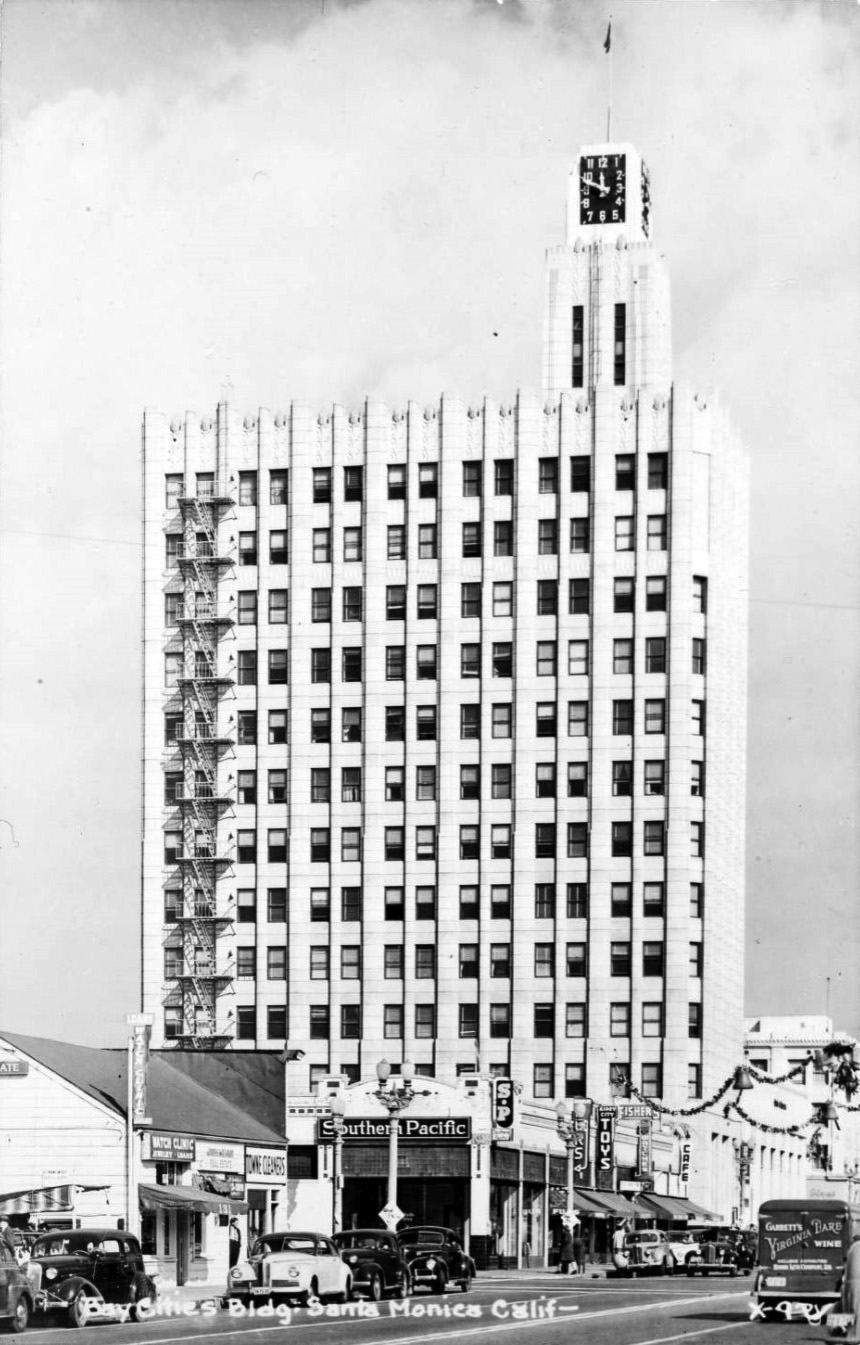

| (ca. 1926)#^ – View showing the intersection of Fourth Street and Santa Monica Boulevard with Santa Monica City Hall on the northwest corner, Security Trust and Savings Bank on the northeast corner, the Henshey-Tegner Building on the southeast corner, and Pacific Southwest Bank on the southwest corner. |

Historical Notes In the 1920s, Santa Monica was thriving both as a popular tourist destination and as home to a budding aviation industry and other businesses. Though Santa Monicans had long trekked to downtown Los Angeles for important shopping, Santa Monica’s downtown was at last coming into its own as a full-service retail center. Henshey’s Department Store, founded by Harry C. Henshey and his partners, was crucial to this change. *##^ |

Henshey's Department Store

|

|

| (ca. 1925)*##^ - View looking at the southeast corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Fourth Street showing the Henshey’s Department Store shortly after it was constructed. |