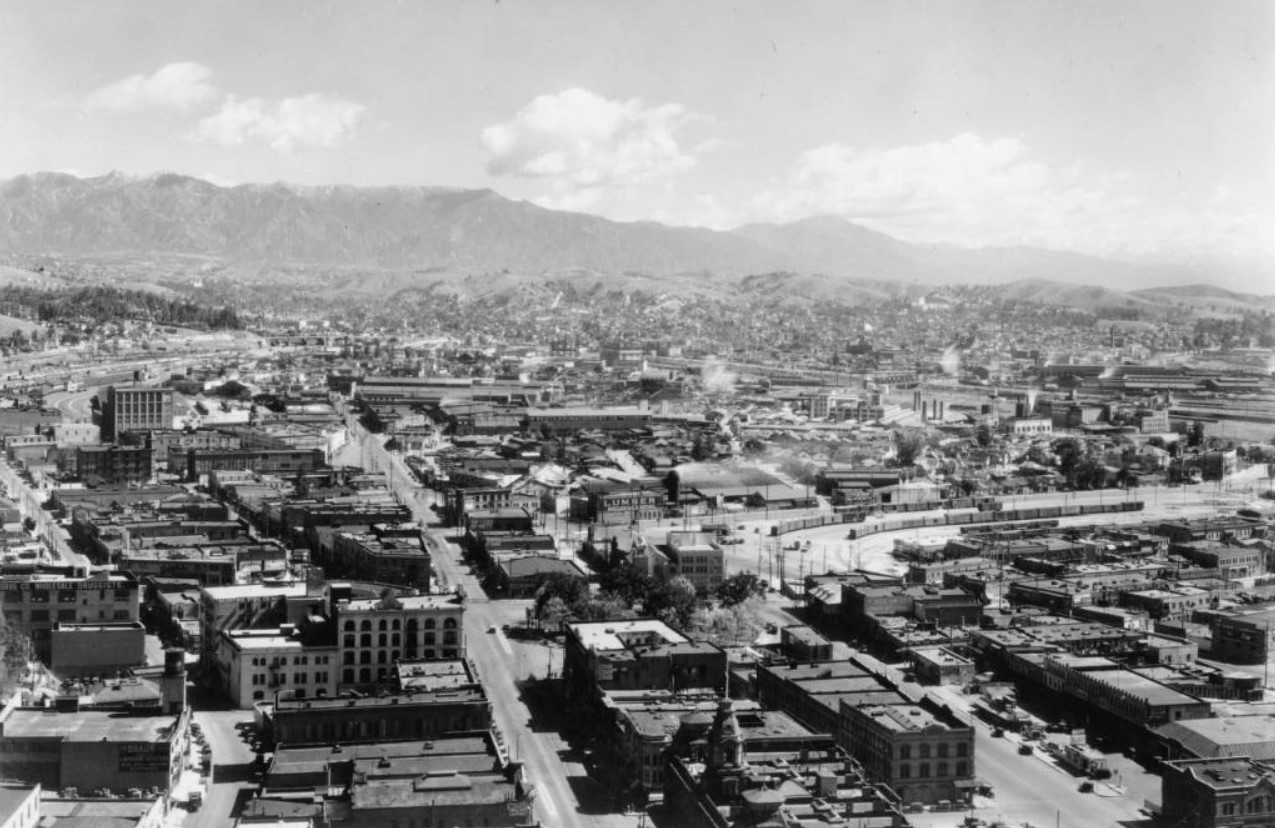

Early Views of the Los Angeles Plaza

Historical Photos of Early Los Angeles |

|

|

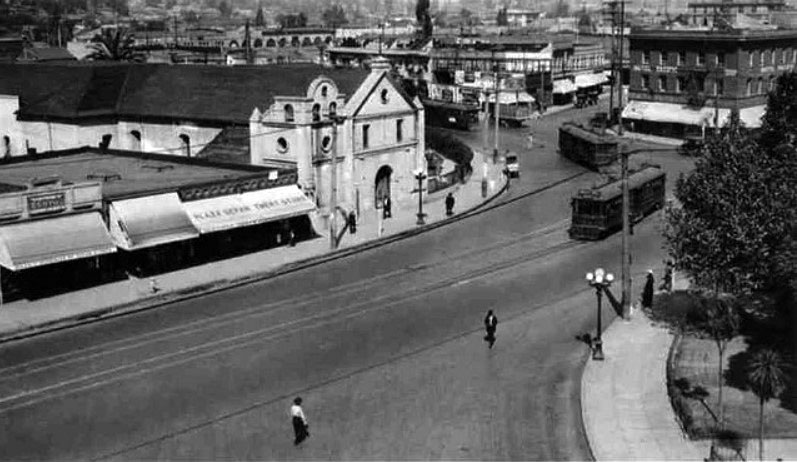

| (ca. 1900)* - View of the Old Mission Church from across the LA Plaza. Several men are seen relaxing on the Plaza's benches. In the background on top of Fort Moore Hill stands Los Angeles High School. |

Historical Notes This would be one of the last photos taken of the Plaza Church with its gazebo-like tower. It would soon be replaced with a "bell wall" (see next photo) similar to the one it had prior to 1861. |

|

|

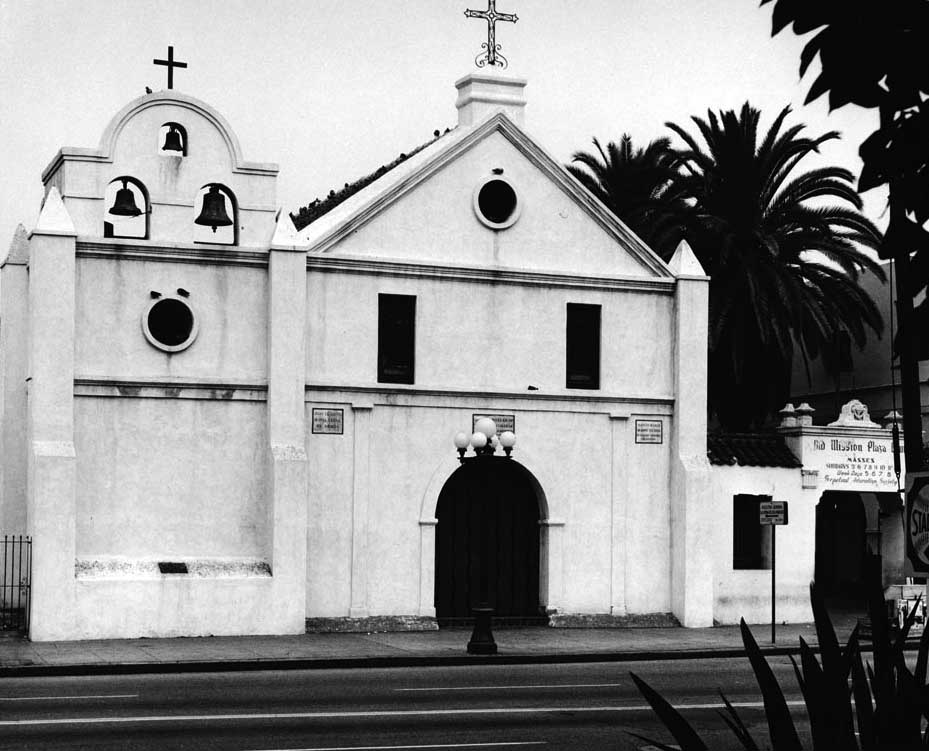

| (ca. 1901)* - Front view of the Old Mission Church with its newly installed "bell wall". There is a clear view of Los Angeles High School up on Fort Moore Hill and its relative relationship to the Plaza and the Plaza Church. |

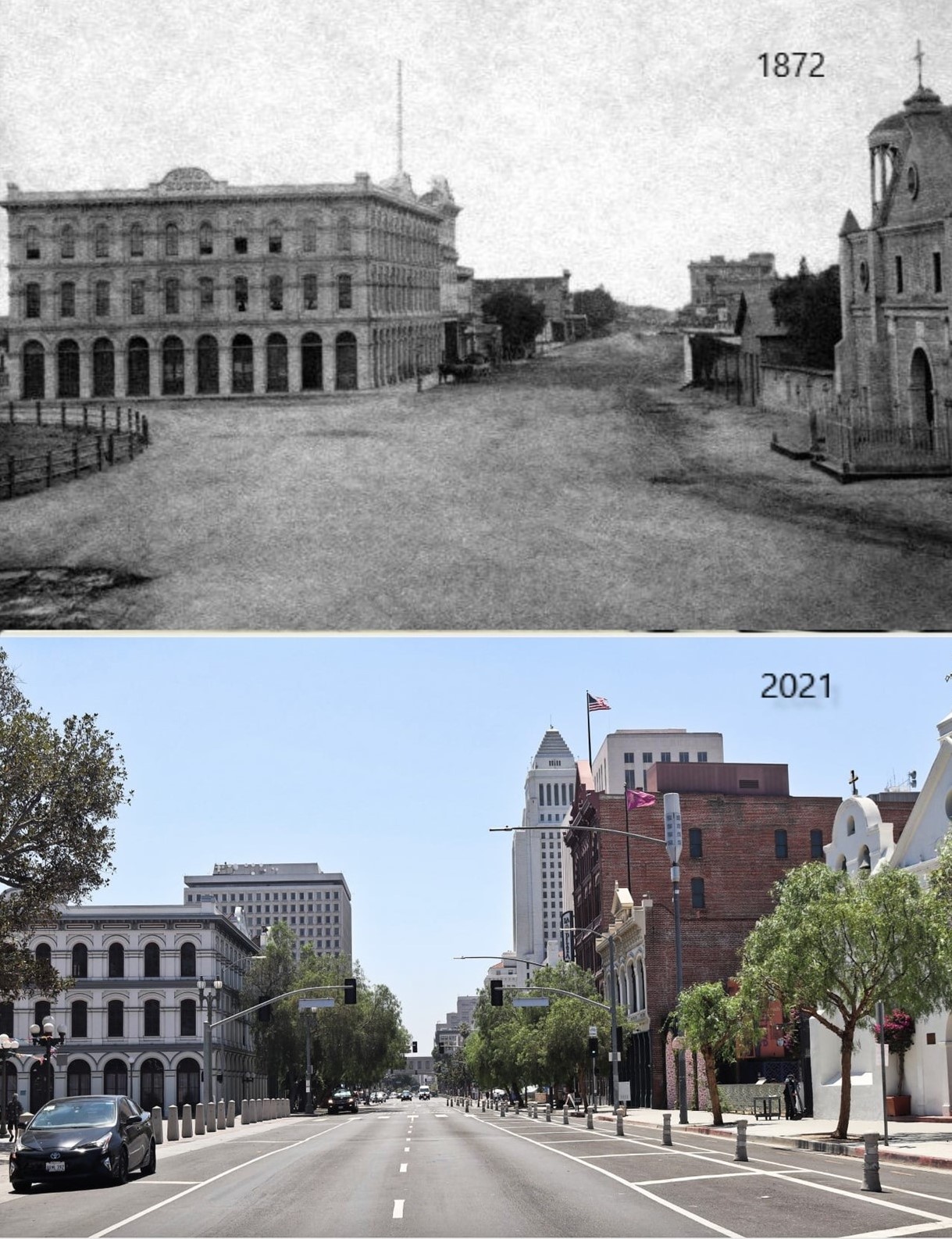

Before and After

|

|

|

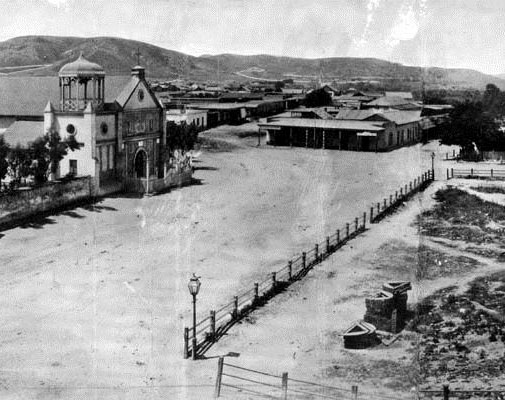

| (1900 vs. 1901)* - Old Mission Church with "Gazebo Tower" and "Bell Wall Tower". |

Historical Notes After the 1861 rebuilding of the Plaza Church, the traditional mission-style bell wall was replaced with a distinctive "gazebo-like" bell tower. This open, ornamental structure stood out as a marked departure from the original adobe campanario and reflected changing architectural preferences of the late 19th century. Prominent in period photographs, the tower became a familiar feature for Angelenos during a time of rapid urban growth, adding a Victorian touch to the historic church’s silhouette. Around 1901, the gazebo-like tower was replaced by a new bell wall resembling the one that had existed prior to 1861. This change signaled a deliberate return to the church’s earlier Spanish Colonial character. Photographic evidence from the time captures this architectural shift, with one image showing the church just before the tower’s removal and another depicting the newly installed bell wall. By 1915, further modifications were made, including the construction of a new bell gable, illustrating the church’s ongoing effort to preserve its historical identity while adapting to the needs and aesthetics of each era. |

Then and Now

|

|

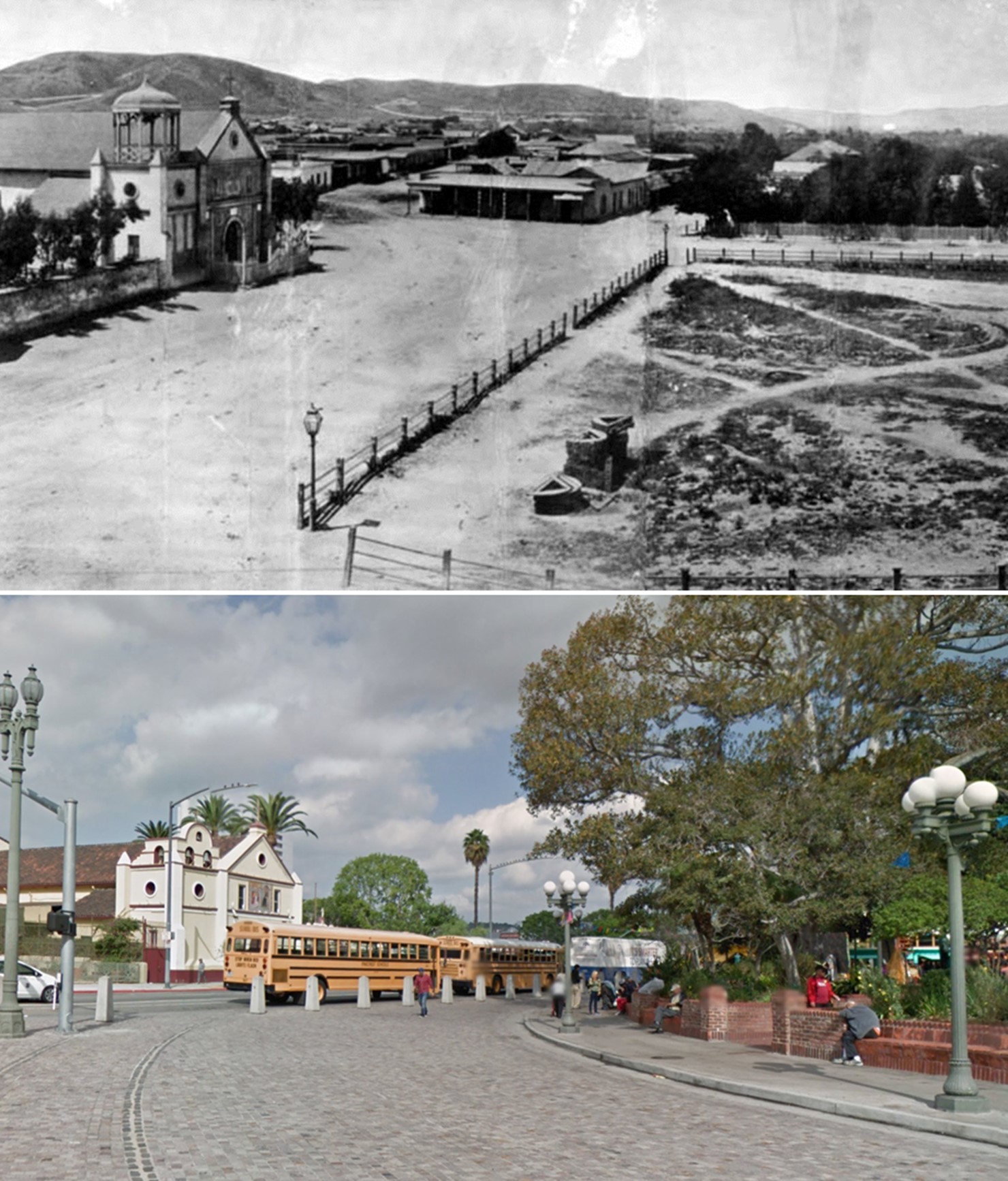

| (1885 vs. 2024)* – A ‘Then and Now’ comparison of the Plaza Church as seen from the Los Angeles Plaza, looking across Main Street. The gazebo-like tower, visible in the 1885 view, was replaced around 1901 by a new bell wall designed to resemble the one that stood prior to 1861. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes Post-1861 photos show the unusual open tower that gave La Placita a late-19th-century silhouette. Around 1901 the parish removed it and installed a three-bell gable to restore a Spanish-Colonial character. By the 1910s, fresh plaster and circular oculi further updated the front, reflecting routine maintenance while nodding to earlier forms. |

|

|

| (ca. 1901)* - View of the 'Old Plaza Mission' (Plaza Church) with its new 3-bell gable. A man and child can be seen crossing the street heading toward the church. |

|

|

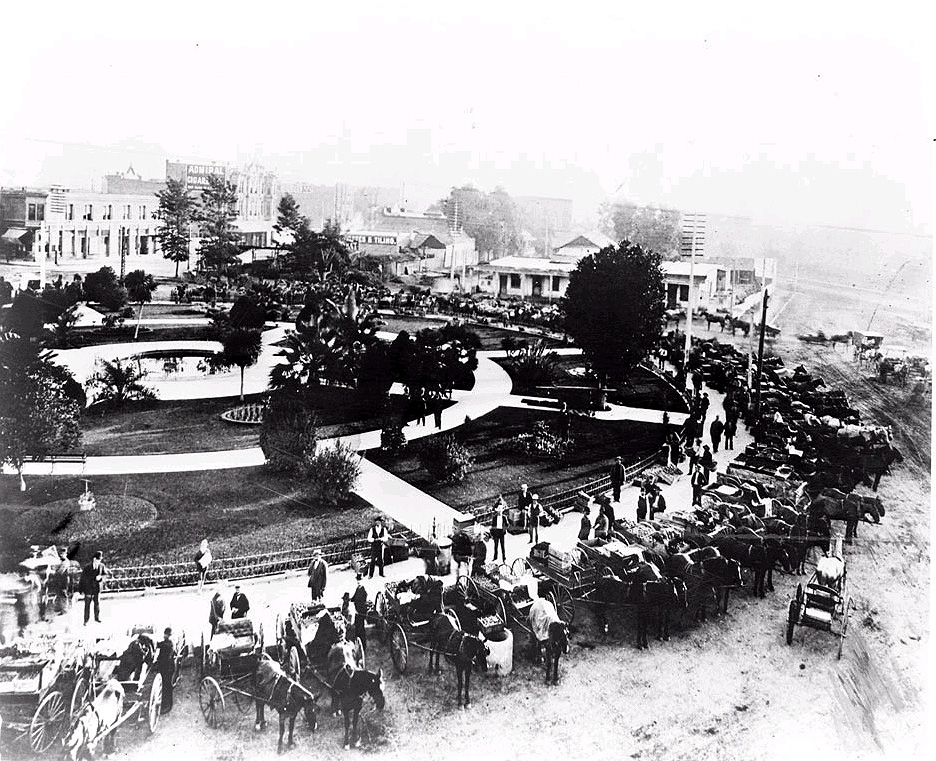

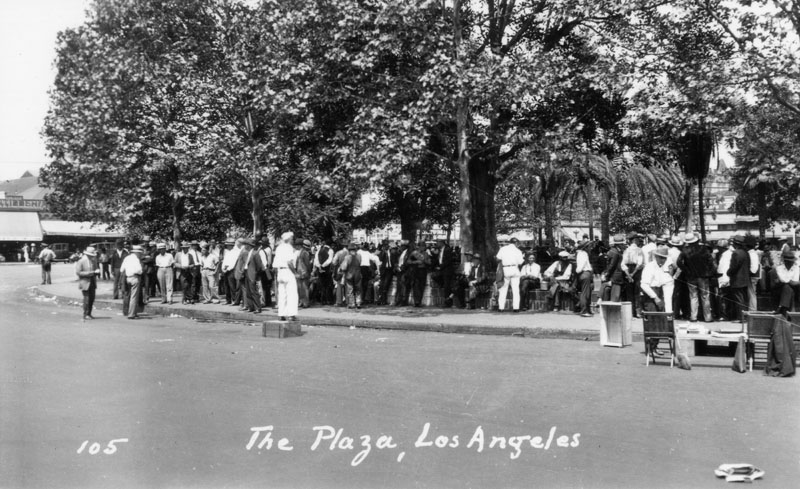

| (ca. 1900)* - Open air market at the Plaza, view is looking northwesterly from the fire house. |

Historical Notes Initially, the majority of vegetable selling in Los Angeles was done around the circular Olvera Street Plaza, just South of Macy Street, where Caucasian, Japanese and Chinese farmers congregated with their goods. However, the increased presence of wagons and the long hours of the makeshift vegetable market became a nuisance to the city. Click HERE to see more about the Los Angeles City Market. |

|

|

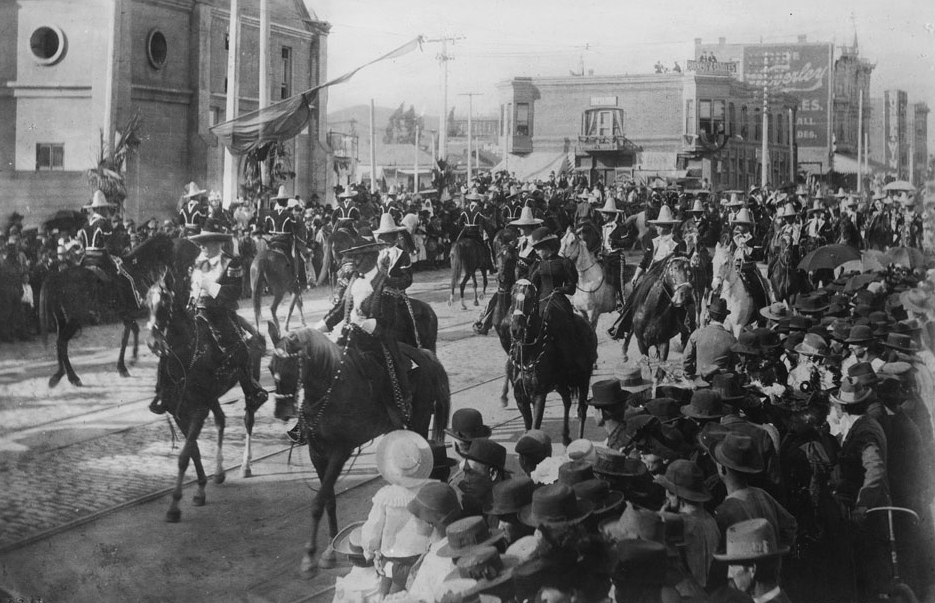

| (1901)* - Caballeros and señoras parading on horseback in front of the Plaza Church during La Fiesta de Los Angeles. Throngs of well-dressed people crowd the sidewalks on both sides of the street. The Grand Marshall of the parade is Francisco Figueroa. The young woman on the horse in black (foreground) is Katie Abbot, daughter of Merced Abbot of Merced Theatre. |

Historical Notes “La Fiesta de Los Angeles” also called "La Fiesta de Las Flores" was a week-long party that the city threw in its own honor during the 1890s and early 1900s. Staged by the Merchants’ Association, it featured parades—a flower parade, a parade with floats, a torchlight procession—and athletic competitions, a costume ball, and a carnival attended by masked revelers. The first fiesta was held in April, 1894. The Spanish title was reflective of a goal: to capture the color and the aura of old Los Angeles in its days as a pueblo under Mexican rule. Men in the garb of caballeros (horsemen) and vaqueros (cow hands) participated. So did Chinese, native Americans, and African Americans. It was a multi-cultural gala, distinct from any celebration elsewhere. |

|

|

| (ca. 1902)* - View showing a group of well-dressed men standing on the edge of the LA Plaza and also across the street in front of the Old Plaza Church. There is a horse-drawn wagon parked by the curb near the church with a streetcar passing by. |

|

|

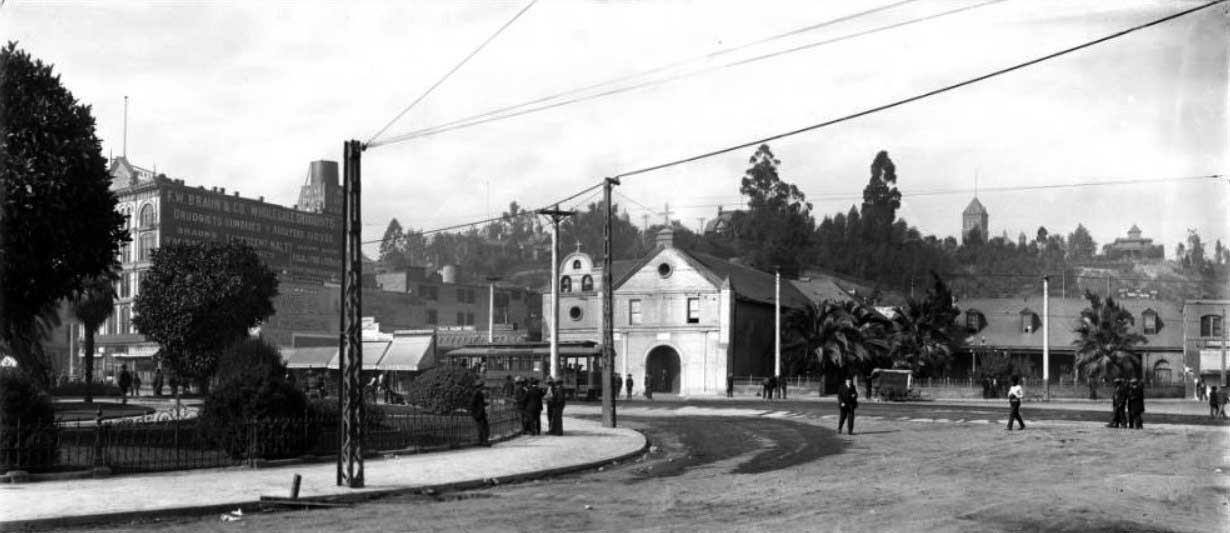

| (ca. 1905)* - Panoramic view of the Los Angeles Plaza, looking west. The F.W. Braun Building, Plaza Catholic Church, and shops along Main Street are visible in the background. Men are sitting, standing or moving about near the church, plaza and along Main Street. An electric streetcar is passing on Main Street carrying about a dozen passengers. Rocks and other forms of debris litter the dirt road. Utility lines and utility poles run along the streets. |

|

|

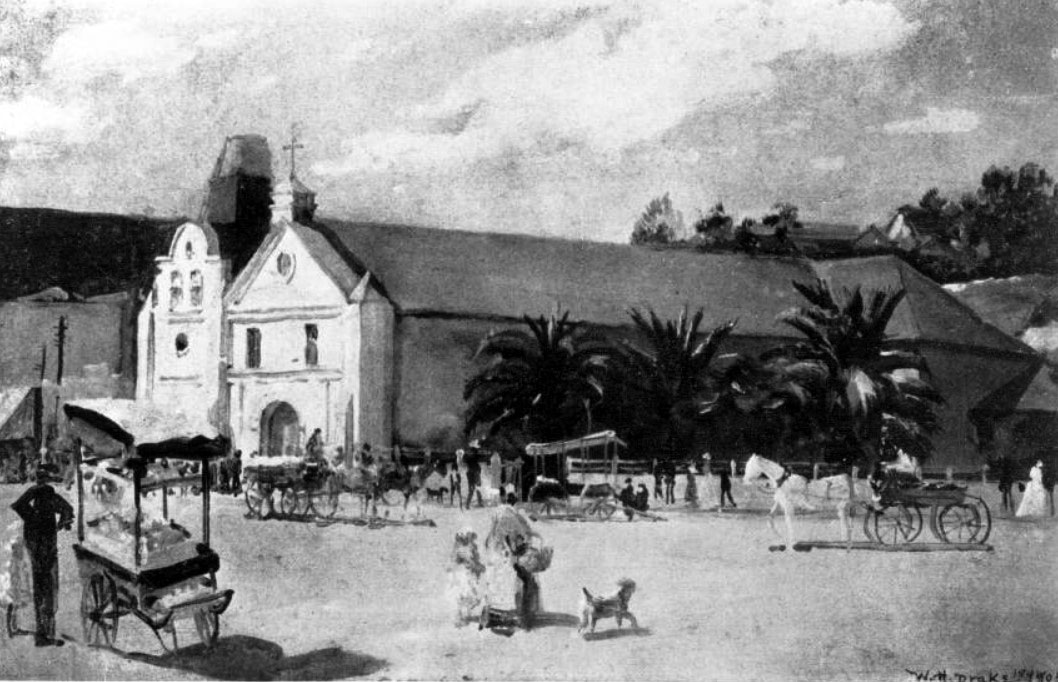

| (ca. 1905)* - Photograph of a painting by Will N. Drake of the old Plaza Church. The painting depicts a street scene in front of the Plaza Church: In the foreground a cart vendor in dark clothing is pictured. Closer to the church itself are several horse-drawn carriages, drawn both by dark and light horses. Between both the vendor and the carriages, towards the center of the image, a woman with a basket holds the hand of a child to her left. They are followed by what appears to be a dog. Short palms line the side of the church. |

|

|

| (ca. 1909)* – Panoramic view showing the front of the Plaza Church. A wire fence and palm trees can be seen to the right of the church, while tall buildings and water tower are visible behind and to the left of the church. A trolley can be seen at left, a cyclist and a pedestrian are visible just to the right of the church, and a horse pulling a carriage or wagon is visible at right. |

|

|

| (1906)* - Raising of the first El Camino Real bell at Los Angeles Plaza near Olvera Street to launch the state’s first road marker program. In the next few years, 450 of the bells were placed along the original mission route from San Diego to Sonoma. |

Historical Notes A story on the original El Camino Real bell appeared in the Aug. 16, 1906 Los Angeles Times: “Quaintly beautiful and picturesque were the ceremonies held at the old Plaza Church yesterday noon in dedication of El Camino Real and also in commemoration of the one hundred and twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the ancient and honorable pueblo of Los Angeles. … Father (Juan) Caballeria made the opening address and announced the object of the meeting. He spoke eloquently of the wonderful growth of the Golden State and the auspicious affair they were celebrating. He told graphically of when the bare feet of the padre of a century ago trod the famous highway that stretched its entire length throughout the entire State and how the padres that followed in the footsteps of the illustrious fathers of former days had endeavored to add their efforts to the building and growth of the great State. A stirring scene followed the termination of Father Caballeria’s address. As he concluded Gen. Antonio Aguilar, one of the last of the old guard that fought under Fremont and was present when Los Angeles was taken by the United States troops, fired a salute and simultaneously the clapper of the bell on the sign post of El Camino Real was raised and throughout the city echoed the sounds of all the bells in the Catholic churches as they tolled in honor of the reopening of the King’s highway again to travel. …” |

|

|

| (1905)* - View showing the Montezuma Saloon "firehouse" across from the Plaza, advertising Zobelein. |

Historical Notes Over its life, the Old Plaza Firehouse was used as a saloon, cigar store, poolroom, "seedy hotel", Chinese market, "flop house", and drugstore. The building was restored in the 1950s and opened as a firefighting museum in 1960. |

|

|

| (ca. 1905)* - Preparation for the Chinese New Year in front of the Montezuma Saloon, previously the Old Plaza Firehouse. |

|

|

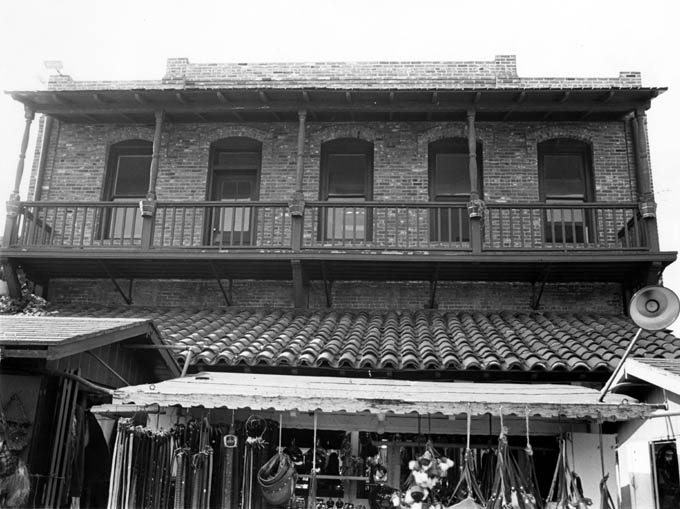

| (1905)* - View showing the two-story Vicente Lugo adobe house, seen with hipped roof and dormer windows. The home is located at 518-520 North Los Angeles Street and Sunset Boulevard, and faces the Plaza. When this photograph was taken, the adobe was home to the Pekin Curio Store with brick buildings flanking it on either side; and the road was still unpaved. |

Historical Notes La Casa de Don Vicente Lugo located on the east side of the El Pueblo Plaza at North Los Angeles Street and Sunset Boulevard. Built in 1839 by Vicente Lugo, it was one of the few two-story homes in Los Angeles at the time. It was donated in 1867 to St. Vincent's College (which later became Loyola University), the first college in Southern California; but later became known as the Washington Hotel, and later, the Pekin Curio Store. Unfortunately, the structure was so altered, that it does not resemble an adobe. |

|

|

| (1915)* - View of a row of two-story buildings with balconies in the 500 block of North Los Angeles Street in Old Chinatown, Los Angeles, with signs for "Fook Wo Lung Curio Co." and "Chew Fun & Co. Chinese Herbs" visible and an automobile parked at the street curb. The buildings face the Los Angeles Plaza (not pictured) and the central building (with three dormer windows) was built for Don Vicente Lugo and known as the Lugo Adobe. |

Historical Notes The site of the Vicente Lugo adobe house was designated California State Historic Landmark No. 301. Click HERE for more about the Vincent Lugo Adobe. |

|

|

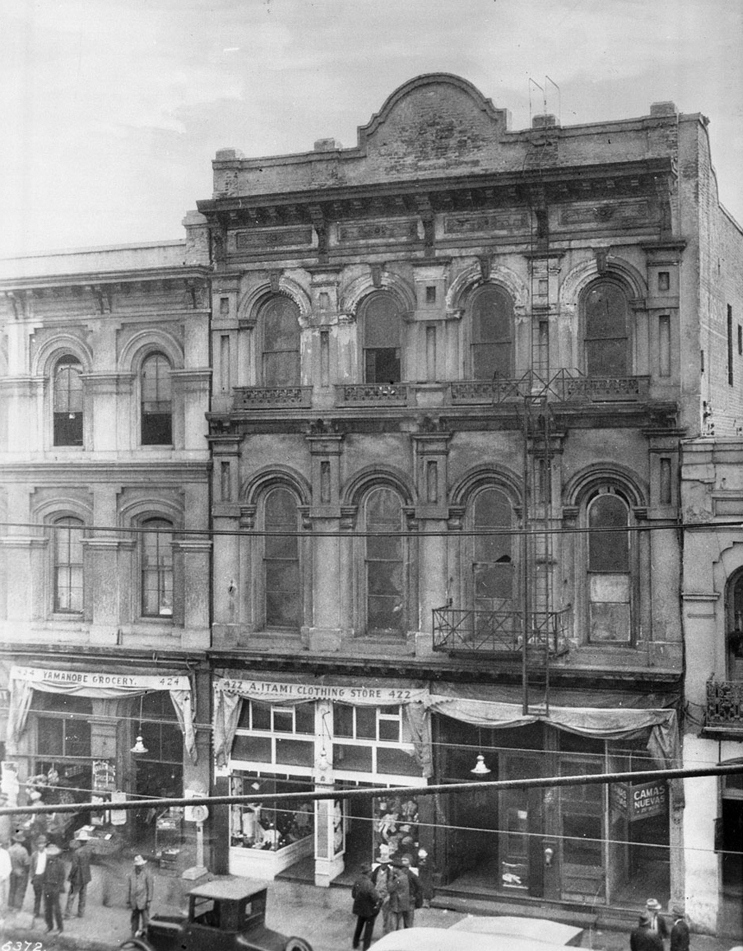

| (ca. 1909)* - Photograph of the Teatro Mercedes (or Merced Theatre). Below the Romanesque architecture of the three-story building, a crowd of pedestrians stand in front of the Japanese shops at ground level which read "A. Itami Clothing Store" and "Yamanobe Grocery". An early model automobile is partially visible in the foreground. |

Historical Notes The Merced Theater, completed on December 31, 1870, opened its first professional engagement on January 30, 1871. It was "used later as an Armory, then again as a Fire Engine house". |

|

|

| (ca. 1910s)** - View of the Avila Adobe house on Olvera Street; a small car is parked along the front of the wooden porch next to one of the staircases. Next door on the right (out of view) is the Los Angeles Railway (LARy) Plaza Substation. |

Historical Notes Don Francisco Avila, a wealthy cattle rancher and one-time Mayor of the pueblo of Los Angeles, built the Avila Adobe in 1818. The Avila Adobe, presently the oldest existing residence within the city limits, was one of the first town houses to share street frontage in the new Pueblo de Los Angeles. |

|

|

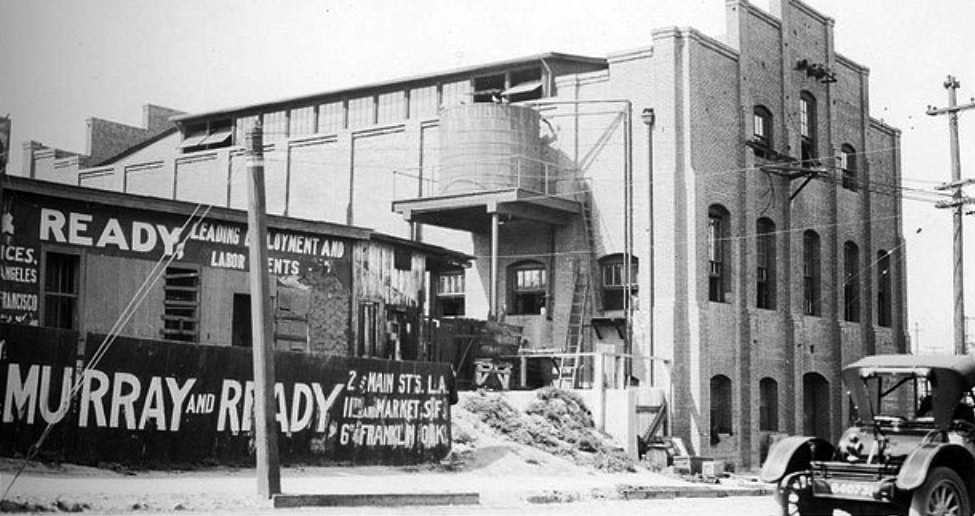

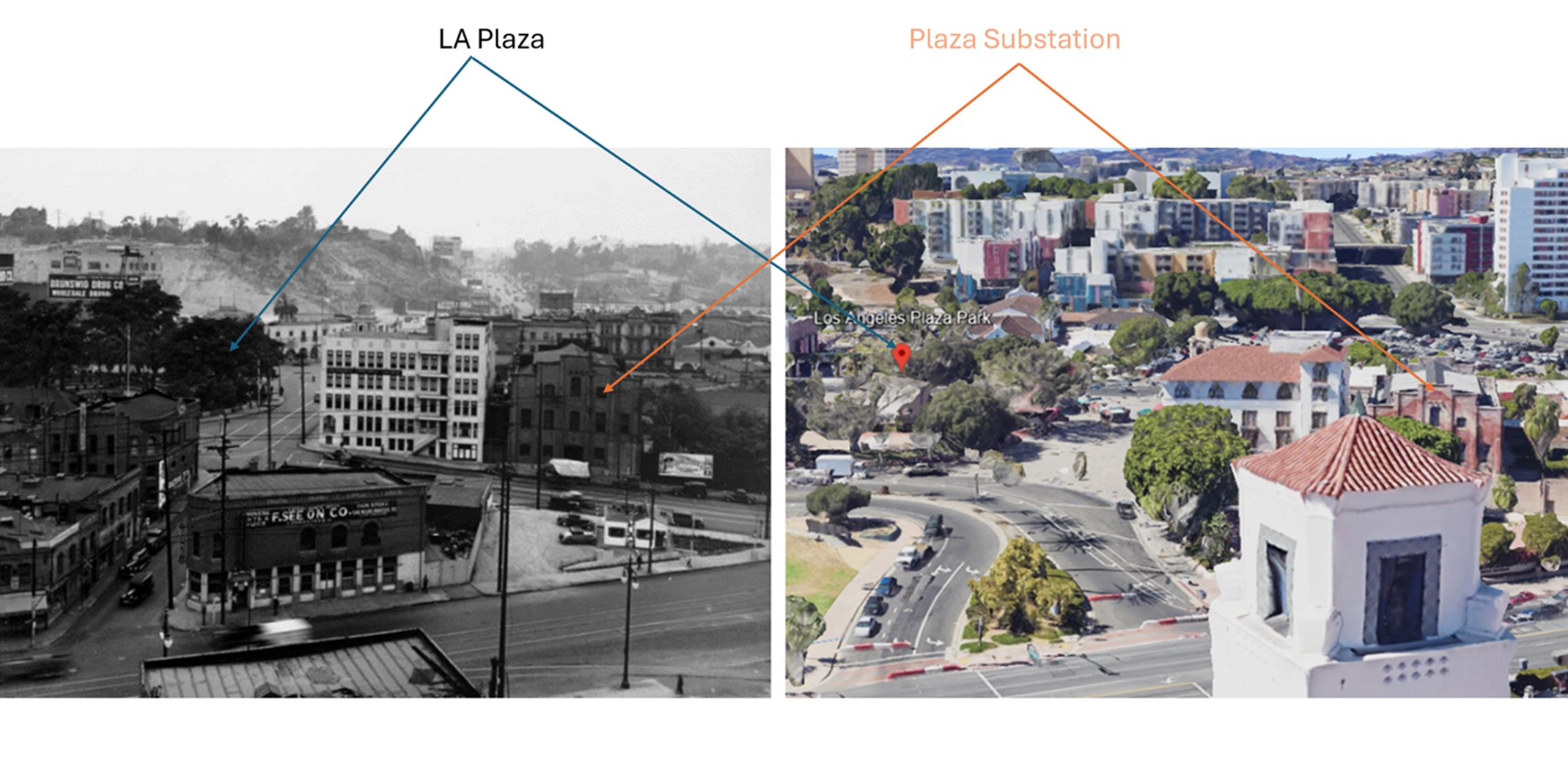

| (1913)#*** – View of the Los Angeles Railway (LARy) Plaza Substation (Eastside). The other side of the substation building fronts Olvera Street and is adjacent to the Avila Adobe. |

Historical Notes The Plaza Substation was an electrical substation that formed a part of the "Yellow Car" streetcar system operated by the Los Angeles Railway from the early 1900s until 1963. After being threatened with demolition in the 1970s, the Plaza Substation was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. |

|

|

| (1913)#*** – Interior view of the Plaza Substation showing three motor-generator sets used to provide electricity for the Los Angeles Railway (LARy). |

Historical Notes In May 1903, Henry Huntington, owner of the Los Angeles Railway, announced plans to build a new substation near the old plaza. The Los Angeles Times reported: "Another mammoth electricity substation is to be constructed by the Los Angeles Railway Company. Its location will be on the Plaza, and its completion will mean a long step forward toward the perfection of a system that already is surpassed by few in this country." The substatin was operating by 1905. The substation is one of the two buildings in the Los Angeles Plaza Historic District that is itself separately listed in the National Register of Historic Places, having been so listed in September 1978 (The Avila Adobe is the other). |

|

|

| (Early 1900s)* - Photograph of the bell of El Camino Real at the Los Angeles Plaza Mission. Behind it is a 1-story brick building with a wooden arched doorway and a dormer window is visible. On the bell in raised lettering "1769 & 1906, El Camino Real". The sign reads: "El Camino Real; San Gabriel Mission, 12 miles, via Aliso St. & Mission Rd.; San Fernando Mission, 23 miles, via Sunset Blvd. & Cahuenga Pass". |

|

|

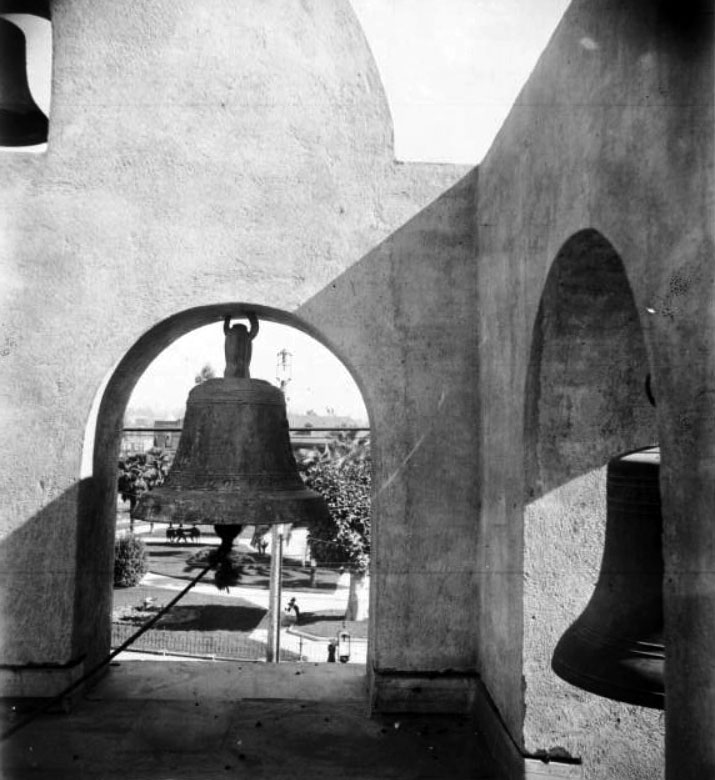

| (ca. 1910)* - View of the bells in the Los Angeles Plaza Church tower. Through one of the tower openings can be seen sidewalks, trees and people in the Plaza. |

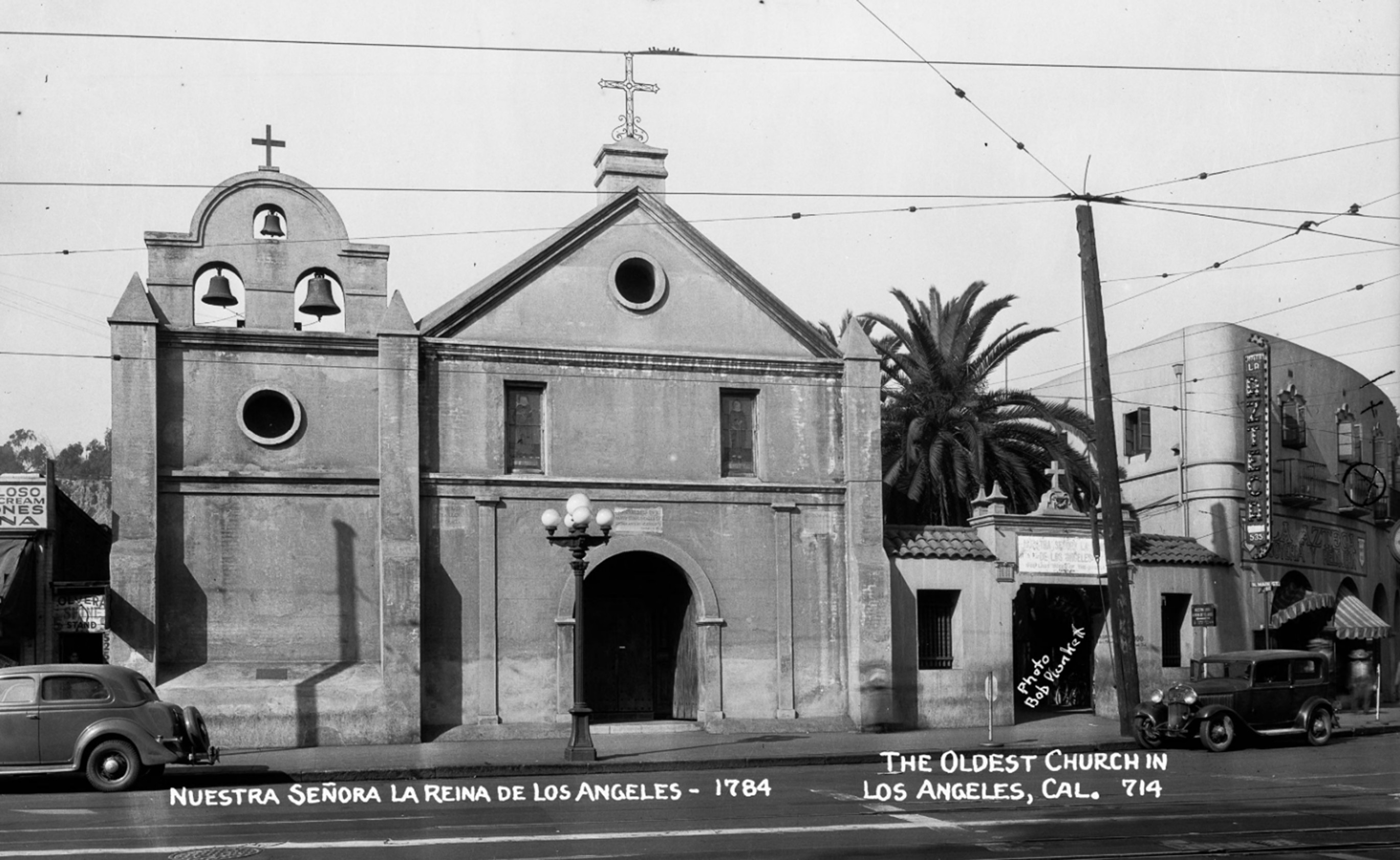

Historical Notes The Plaza Church bells were cast by Paul Revere’s apprentice, George Holbrook. The church, located at 535 North Main Street, is the oldest religious structure in Los Angeles. Originally built as a simple adobe by Franciscan padres with the labor of local Indigenous people, it was completed in 1822 and has remained in continuous use ever since. Later additions included the tile mosaic of The Annunciation (1981) by artist Isabel Piczek, ornate gold-leaf interior decoration, and wrought-iron detailing. |

|

|

| (1910s)* - View of the Old Plaza Church, showing what appears to be a new bell gable. Four churchgoers are seen behind a wrought-iron fence in front of the chapel. In the background on top of Fort Moore Hill can be seen the Banning House. |

Historical Notes During this decade, the church’s façade received fresh plaster and minor architectural repairs, including new round window openings (oculi) and decorative trim. The wrought-iron fence and gates were added to protect the churchyard from the growing flow of traffic and streetcar activity on Main Street. The area behind the church, including Fort Moore Hill, remained largely residential until the late 1930s. |

|

|

| (1915)* – View of the Plaza Church (La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles) on North Main Street, with a small machine shop next door advertising “Oils,” “Batteries,” and “Bicycle Sundries.” Electric trolley wires crisscross overhead, a streetlight stands at the corner, and pedestrians pass by—capturing a moment when old Los Angeles met the modern age. |

Historical Notes By 1915, Plaza Church stood as a relic of old Los Angeles amid a fully urbanized downtown. Next door, a small machine and bicycle shop at 521–523 N. Main symbolized the city’s technological age—advertising oils, batteries, and vulcanizing services. Overhead trolley wires, streetlights, and pedestrians reflected a city rapidly moving forward. The shop likely stood on ground once part of the church’s early burial yard, long since built over after burials were moved to Calvary Cemetery. Beneath the signs of progress, traces of the city’s earliest days remained—while the church itself continued to bridge Los Angeles’ colonial past with its industrial present. |

|

|

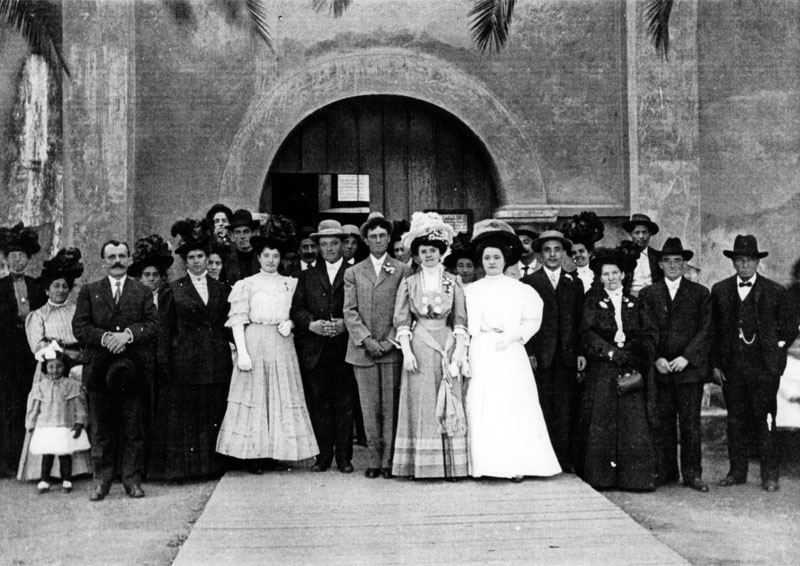

| (ca. 1917)* - A wedding at the Plaza Church in downtown Los Angeles. Maria Bidart Erramauspe is the bride. Several members of the Bidart family, originally from the Basque region in France and early settlers in Los Angeles, are present. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of the front of the Old Plaza Church as seen from the L.A. Plaza across the street. Early model cars are seen parked in front of the church. |

Historical Notes With automobiles replacing trolleys and wagons, the Plaza area entered a new era of transformation. Though many nearby adobe structures had disappeared, Plaza Church remained an active parish serving the largely Mexican-American community that now lived around Sonoratown. Its continued use helped preserve the religious and cultural traditions that had defined Los Angeles for over a century. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)^- Plaza Fountain. Several men appear to be reading the daily newspaper. A horse drawn wagon can be seen in the upper left. |

|

|

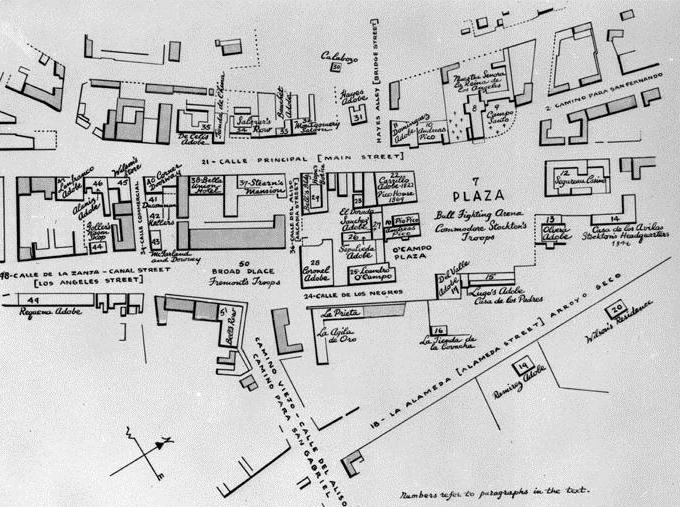

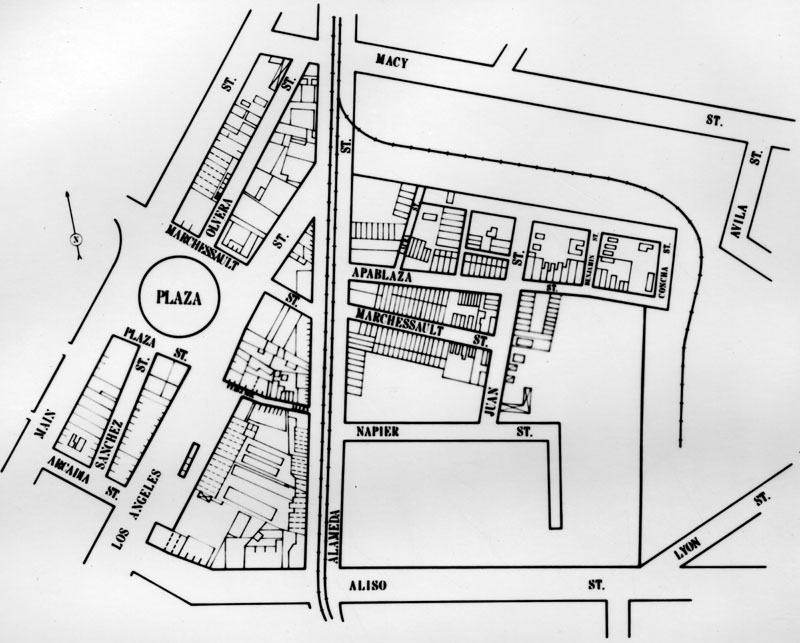

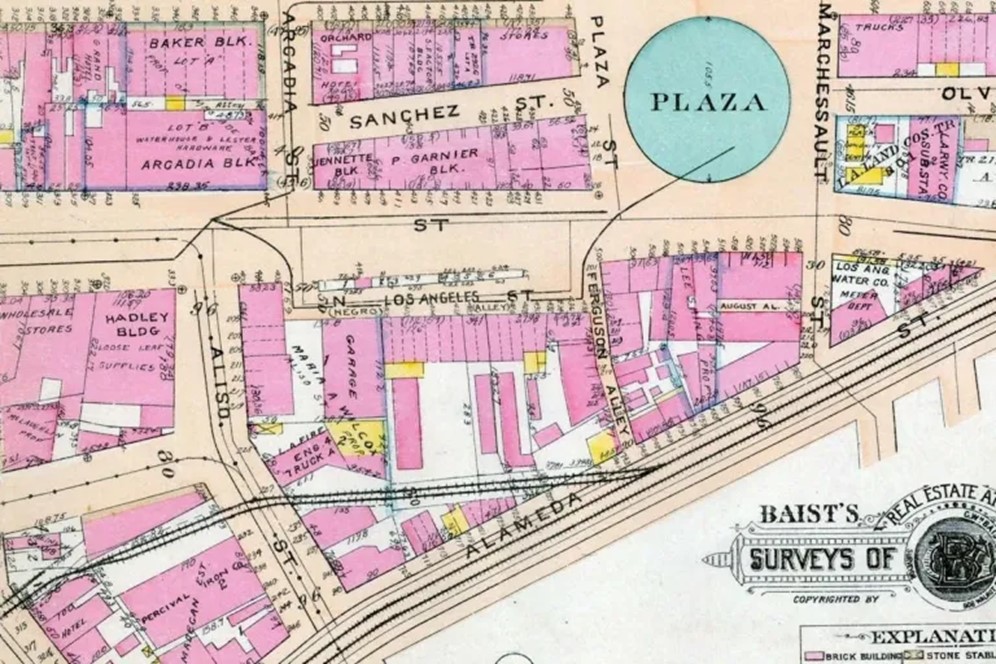

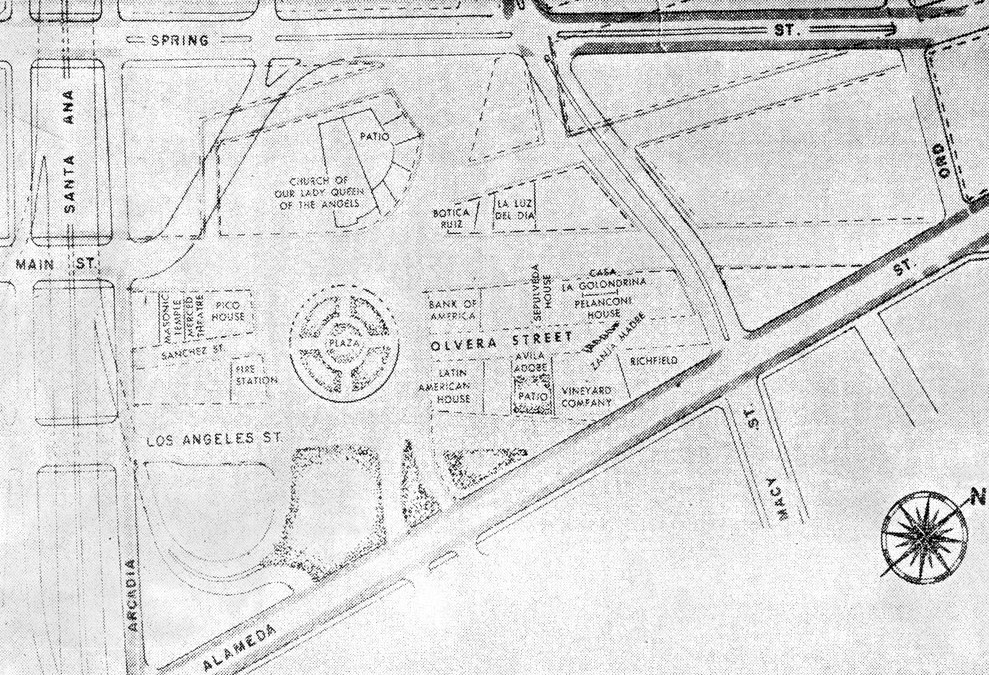

| (Early 1900s)* - Detailed map of the LA Plaza area in its early days. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920)** - View of North Main Street at Arcadia Street in the Plaza area circa 1920. From left to right: Pico House, Merced Theater, Masonic Temple, and Hotel Orchard on the corner of Arcadia Street. Small shops are at street level, and cars are parked along the curb. Streetcar tracks are in the foreground. |

|

|

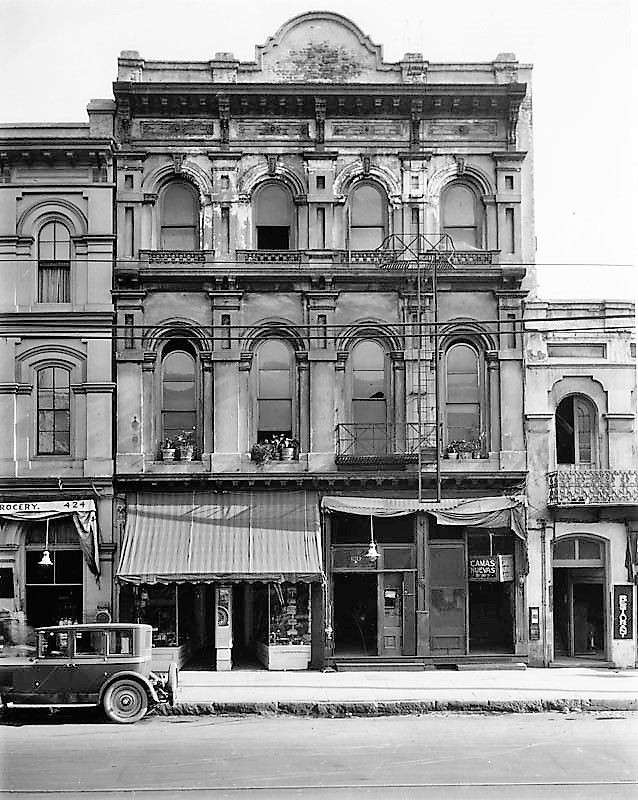

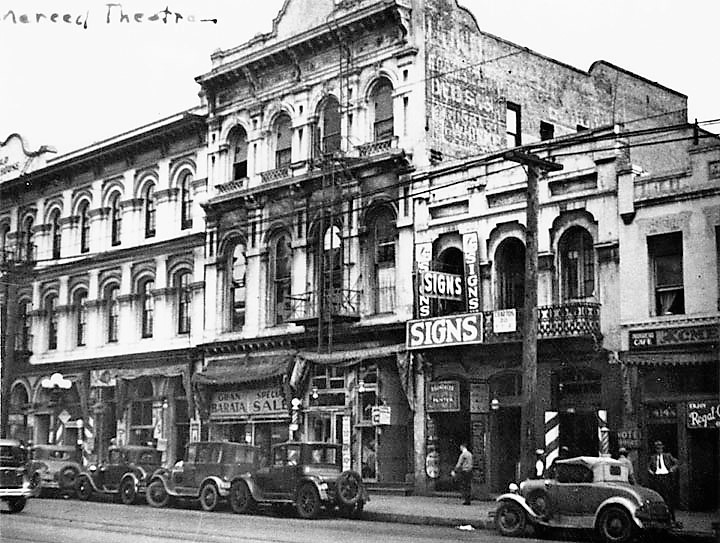

| (1920s)* - View of the Merced Theater as seen from across the street with commercial stores seen on the ground level. |

|

|

| (late 1920s)* – The Merced Theater is wedged between the Pico House and the Masonic Hall. |

|

|

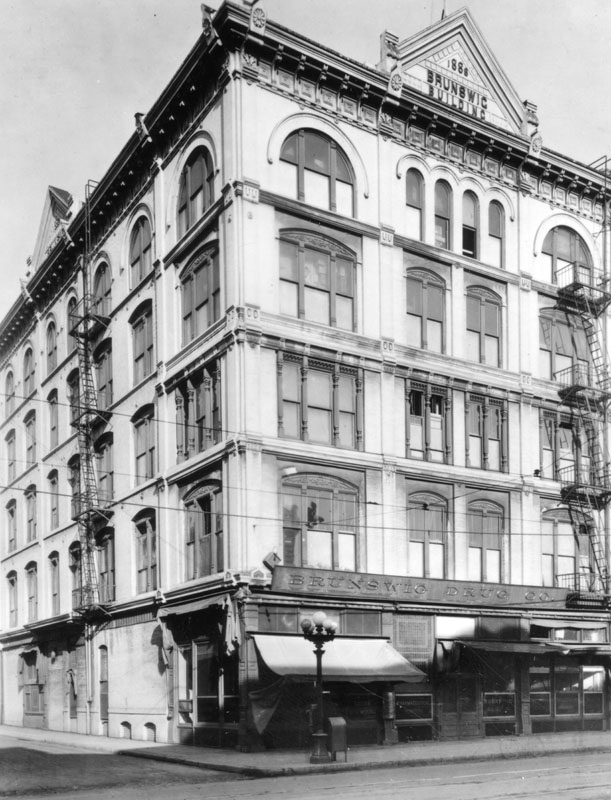

| (ca. 1920)* - View of the Vickrey-Brunswig Building located on the northwest corner of N. Main and Republic streets. The name of the building appears on two signs, one over the doorway and one on top of the roof. |

Historical Notes Prominent architect Robert Brown Young designed the Vickrey-Brunswig Building in a transitional Italianate style, varying the treatment of each story of the facade for greater visual interest. The windows of the upper floor feature Romanesque arches, while those of the third floor are embellished with turned posts that serve as the mullions between the grouped sashes. R. B. Young was the principal of one of Los Angeles's earliest architectural firms, R.B. Young & Son. Young's office garnered a number of prestigious hotel commissions, such as the Clifton (his first commission in Los Angeles, at the corner of Broadway and Temple Streets), Lankershim, Westminster, Lexington, Hollenbeck, and Occidental hotels. Young also designed the Lankershim office building, the Barker Brothers' block, the Wilson Block, and the California Furniture Company. |

|

|

| (ca. 1921)** - Closer view of the Vickrey-Brunswig Building located at 501 N. Main Street. The roof sign reads: 1888 - Brunswig Building. The sign over the building entrance reads: Brunswig Drug Co. |

Historical Notes The Vickrey-Brunswig Building was constructed of brick on a trapezoidal plan and stands five stories with a full basement. It was constructed in the Italianate style commonly used for commercial architecture in the Iate-19th and early 20th centuries. Characteristic elements of the building include the decorative stringcourse located above the fifth floor windows and the segmental and rounded arched brick windows featured on the south and west elevations. |

|

|

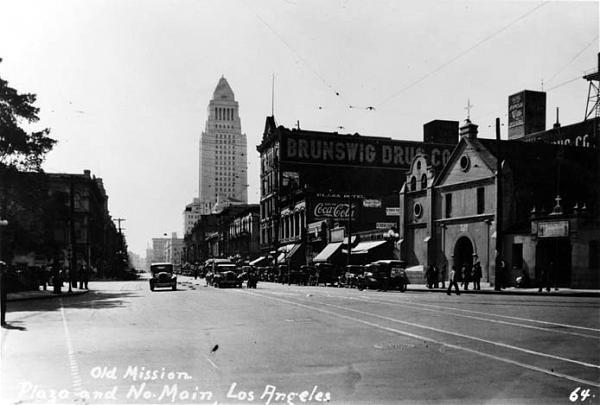

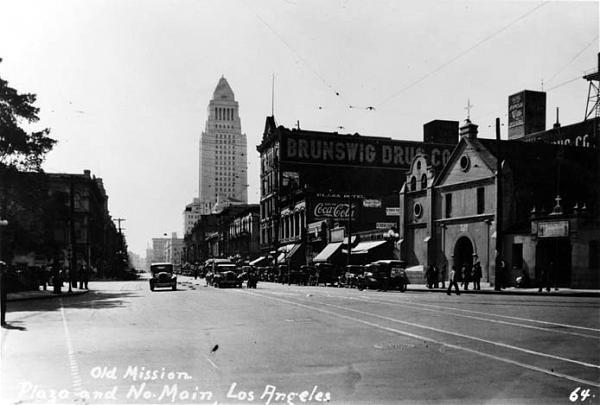

| (1920)*#^ - View looking south on Main Street showing the Old Plaza Church and Brunswig Building (Brunswig Drug Company) on the right and the LA Plaza and Pico House on the left. The new City Hall which would stand two blocks south would not be built until 1928. Early model cars share the road with electric streetcars. |

Historical Notes Note the elevated kiosk on the edge of the plaza to the left of photo. Elevated booths like these were used by the Los Angeles Railway and the Yellow Cars as a switchman’s tower to control the flow and path of streetcars through the intersection. Many of these were still standing well into the 1920s. |

|

|

| (ca. 1928)* - View looking south on Main Street showing the newly constructed City Hall standing in the background (corner of Temple and Main streets) with the Brunswig Building and Old Plaza Church at right. |

|

|

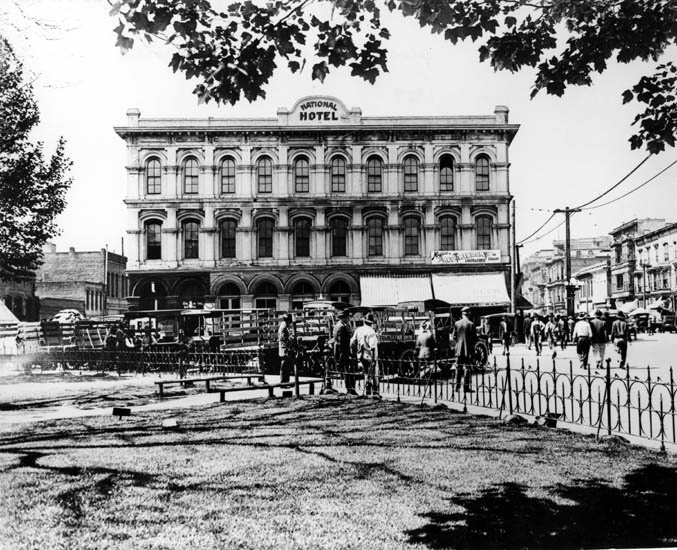

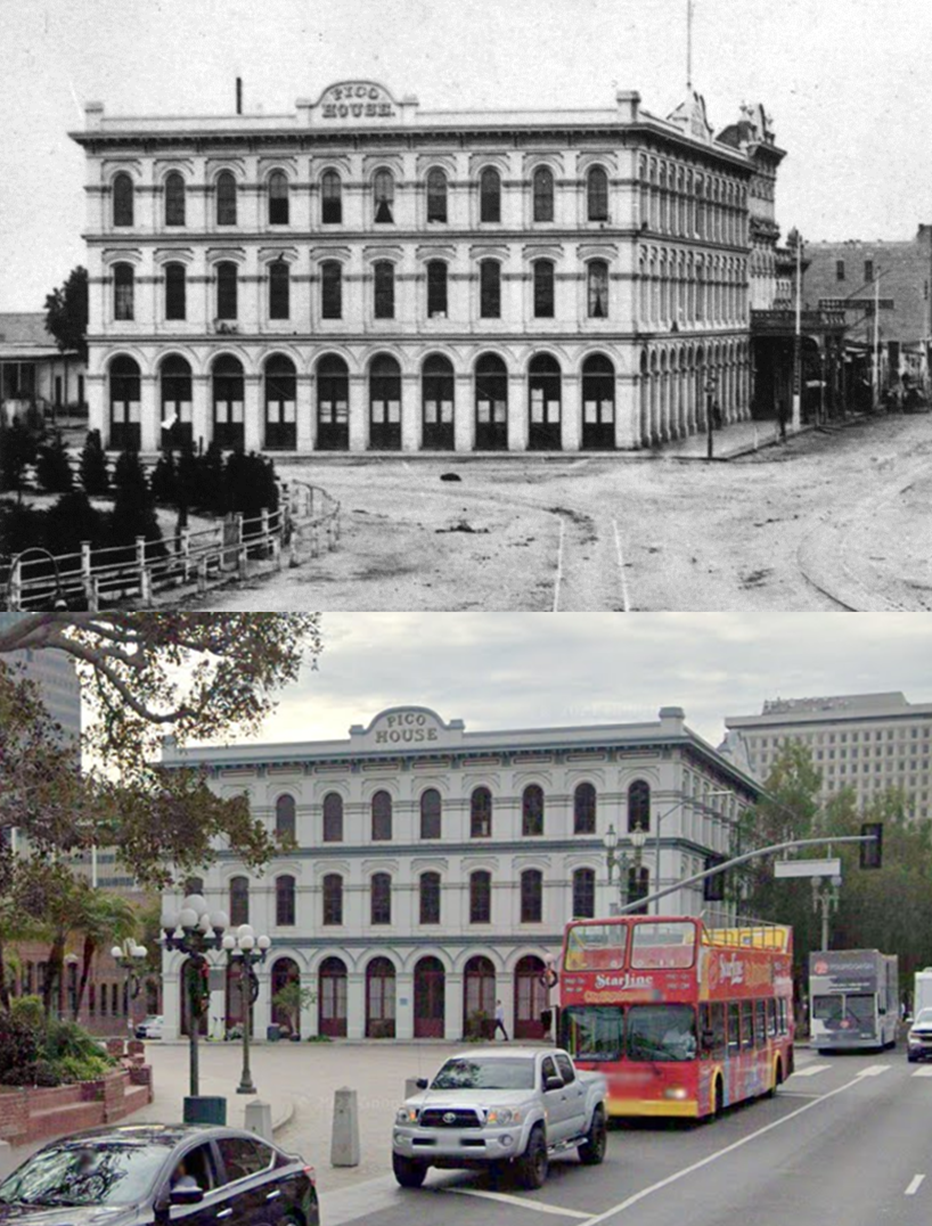

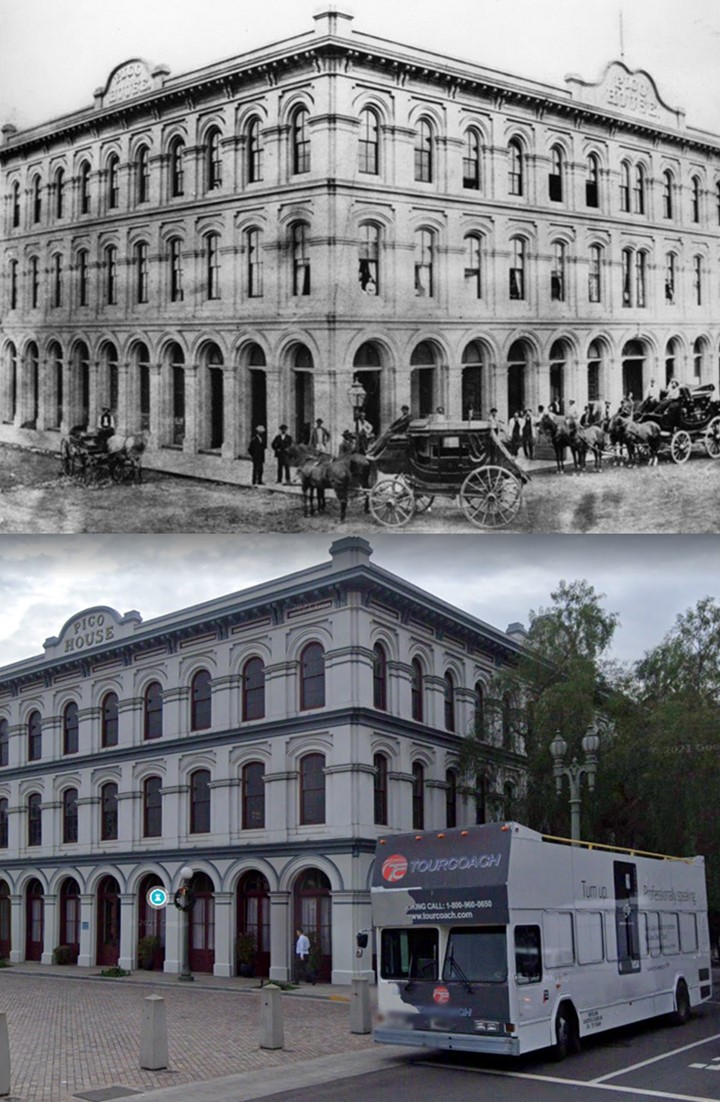

| (ca. 1920)*#^ - View of the Pico House as the National Hotel from the Plaza circa 1920. |

Historical Notes In 1880, Pico lost the hotel by foreclosure. From 1892-1920 the building was called the National Hotel. |

|

|

| (ca. 1920)** - Corner view of the Pico House as the National Hotel with a sign for "Plaza Employment Agency" on the right side of the building. A crowd of people are hanging around the corner, and a row of cars is parked up the left side, while 3 or 4 cars are seen on the right side. |

|

|

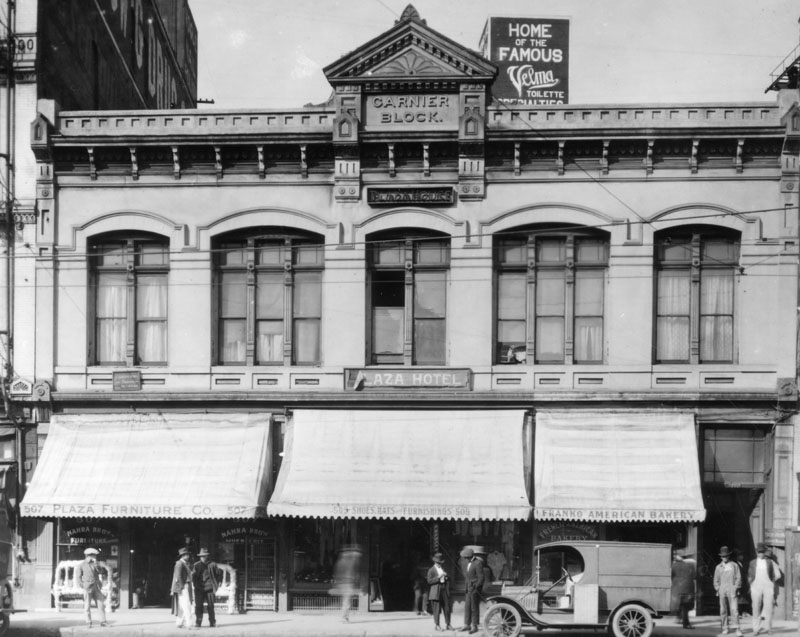

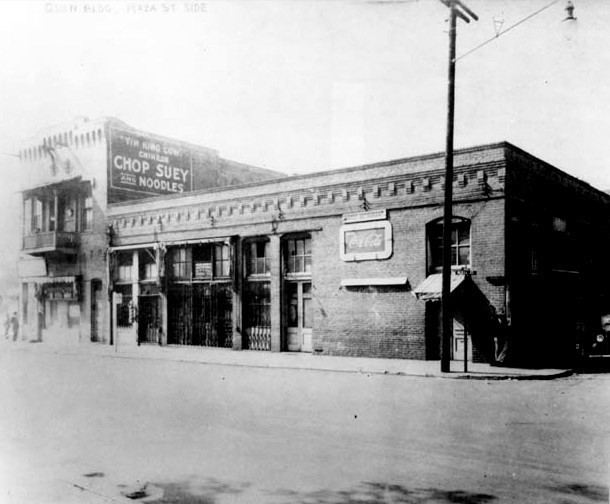

| (ca. 1920)** - Garnier Block, formerly known as the Plaza House had shops on the ground level and the Plaza Hotel on the second floor. A short distance to the right (out of view) sits the Old Plaza Firehouse. |

Historical Notes The Garnier Building was designed primarily for Chinese commercial tenants. It is the oldest building in Los Angeles exclusively and continuously inhabited by Chinese immigrants from the time of its construction in 1890 until the State took it over in 1953. The building was the headquarters of major Chinese American organizations and housed businesses, churches, and schools. It was an important structure in the original Los Angeles Chinatown. |

|

|

| (ca. 1925)** - On the left is the Jennette Block on the northwest corner of Arcadia and Los Angeles Streets, and on the right is the Garnier Building at 415 North Los Angeles Street. The construction of the #101 Freeway took away the Jennette Block and left the Garnier Building. |

|

|

| (1920s)*#^ - The Olvera Street side of the Pelanconi and Sepulveda Houses prior to restoration. |

Historical Notes Sepulveda House is a 22-room Victorian house built in 1887 in the East lake style. The original structure included two commercial businesses and three residences. Pelanconi House, built in 1857, is the oldest surviving brick house in Los Angeles. In 1930, it was converted into a restaurant called La Golondrina, which is the oldest restaurant on Olvera Street. |

|

|

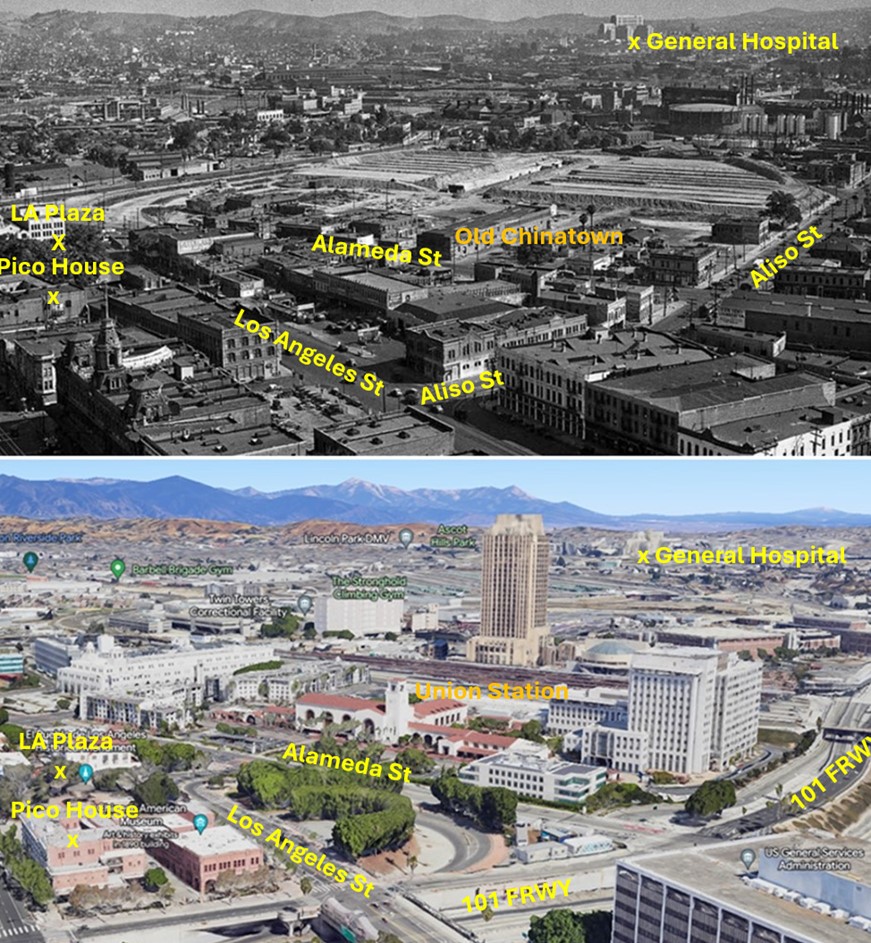

| (1920s)** - Map of early LA with the Plaza seen just west of Alameda. East of Alameda is the older part of Chinatown that was relocated when the Union Station was built in the late 1930s. Union Staion opened in May of 1939. |

|

|

| (n.d.)* - View of Sanchez Street, lined with brick buildings, looking toward the Plaza. |

Historical Notes This small street, which ran south of the Plaza, was officially named in 1861 for Tomas Avila Sanchez, through whose property it passed. Sanchez was elected Sheriff of Los Angeles County 17 times. He resided for many years in a Glendale adobe. |

|

|

| (1921)* - View of Sanchez Street, lined with brick buildings, looking north toward the Plaza in 1921. The first building at far left is the rear side of the Pico House and the rear side of the Merced Theater. |

Historical Notes Sanchez Street juts south from the plaza, opposite its more famous twin, Olvera Street, on the north side. It's just a block long, but it's seen a lot of history. In the 1880s and '90s, it was the scene of several crimes reported in The Times. Most involved the local saloons and Chinese gangs of the day, including the 1889 shooting death of the "Peruvian Princess," a woman whose tortured life took her from Lima to China to San Francisco and finally to her death in a Sanchez Street boarding house. In 1914 police fought protesters on Sanchez Street during the Christmas Riot. A member of the International Workers of the World, or Wobblies, was shot and killed. |

|

|

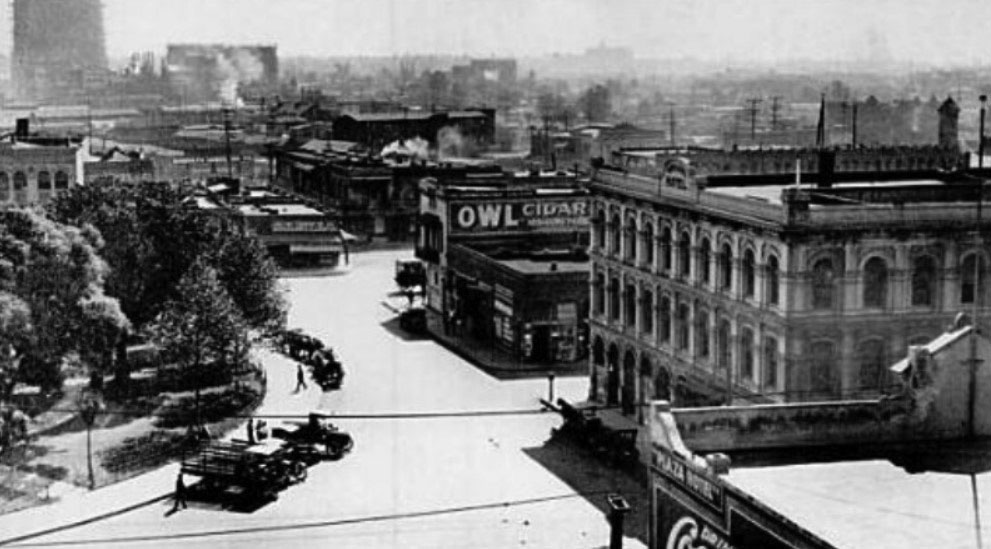

| (1918)* – View looking down from the top of the Plaza Church showing (L to R): the LA Plaza, the Old Fire Station with “Owl Cigar” billboard on its side, Sanchez Street, and the Pico House. |

|

|

| (1920s)** - View showing the El Pueblo Hellman/Quon Building on the southeast corner of Republic and Sanchez streets, across from the Plaza, with the Old Fire Station on its left. |

Historical Notes The Hellman/Quon building is named for its two long-time owners, a white European builder and a Chinese businessman. When Hellman, the original owner, died in 1920, the building was sold to Quon How Shing, who helped fellow Chinese learn English and taught them how to adapt to American society. The building had a hidden bell to alert occupants to the presence of unwelcome visitors who might take issue with the gambling and opium smoking within. It is now the offices of Las Angelitas del Pueblo, the volunteer organization that offers free tours of El Pueblo de Los Angeles, and El Pueblo Education Center. The Hellman/Quon Building site was where Governor Pio Pico's Office once stood, the last California capital of Mexico. |

|

|

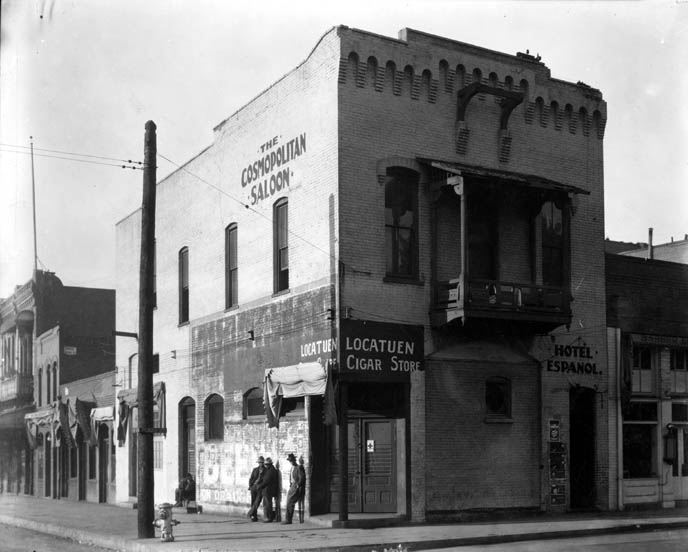

| (1920s)*#^ - View of the Firehouse with three men standing at the corner, when it was the Cosmopolitan Saloon. The sign over the corner doorway reads: Locatuen Cigar Store. |

Historical Notes Over its life, the Old Plaza Firehouse was used as a saloon, cigar store, poolroom, "seedy hotel", Chinese market, "flop house", and drugstore. The building was restored in the 1950s and opened as a firefighting museum in 1960. |

|

|

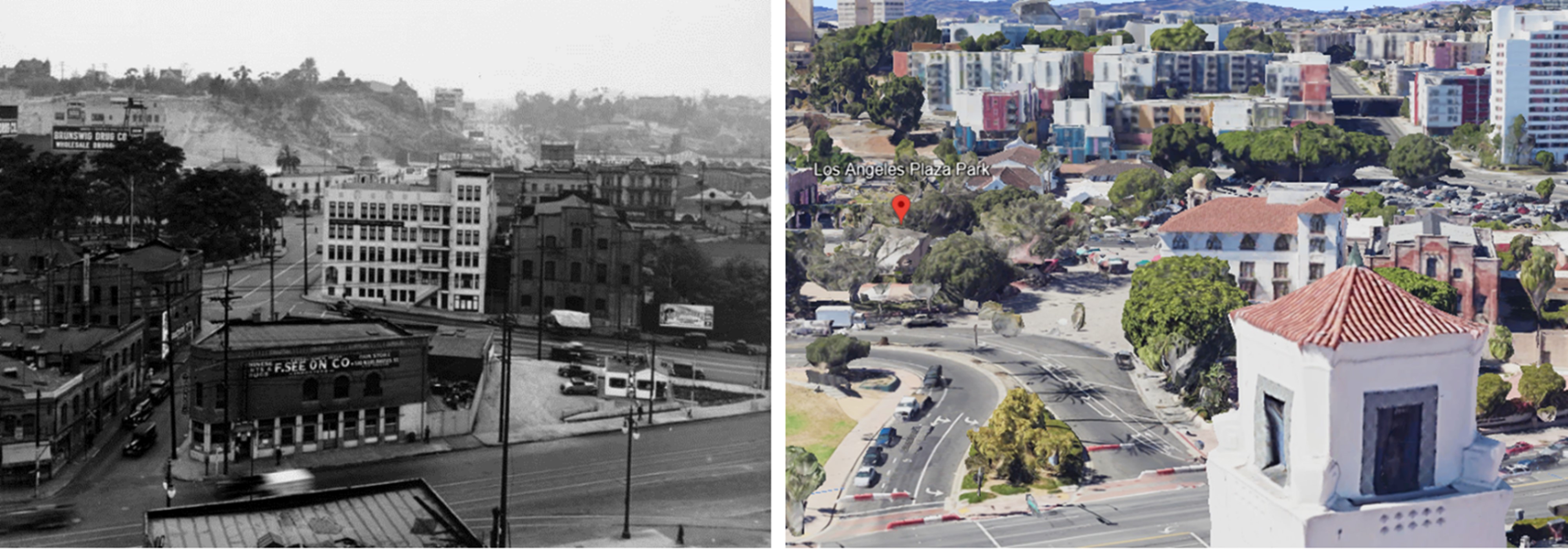

| (ca. 1924)** - Aerial view of the Los Angeles Plaza and surrounding buildings. The streets from top to bottom are: Alameda Street running diagonally at the upper left, Los Angeles Street, and Main Street. Nearly half the buildings to the right of the Plaza (south of the Plaza) were demolished in the 1950s to make way for the Hollywood Freeway. |

Historical Notes The sole occupant of the entire city block bounded by Los Angeles, Marchessault, and Alameda streets (upper left corner of the photo) was a sturdy, square, two-story brick structure. Built originally for a furniture factory, it was later remodeled to serve as a headquarters of the Los Angeles Water Department’s predecessor, the Los Angeles City Water Company. Click HERE to see more in Water Department's Original Office Building. |

|

|

| (ca. 1924)#*** - View looking north on Main Street with the Los Angeles Plaza visible in the upper right. A Los Angeles Railway (LARy) streetcar and several early model autos are seen on Main Street. |

|

|

| (1920s)^^^ – View looking northwest toward The Plaza Church from second floor of The Pico House. Three LARy streetcars are seen near the Old Plaza Church. |

|

|

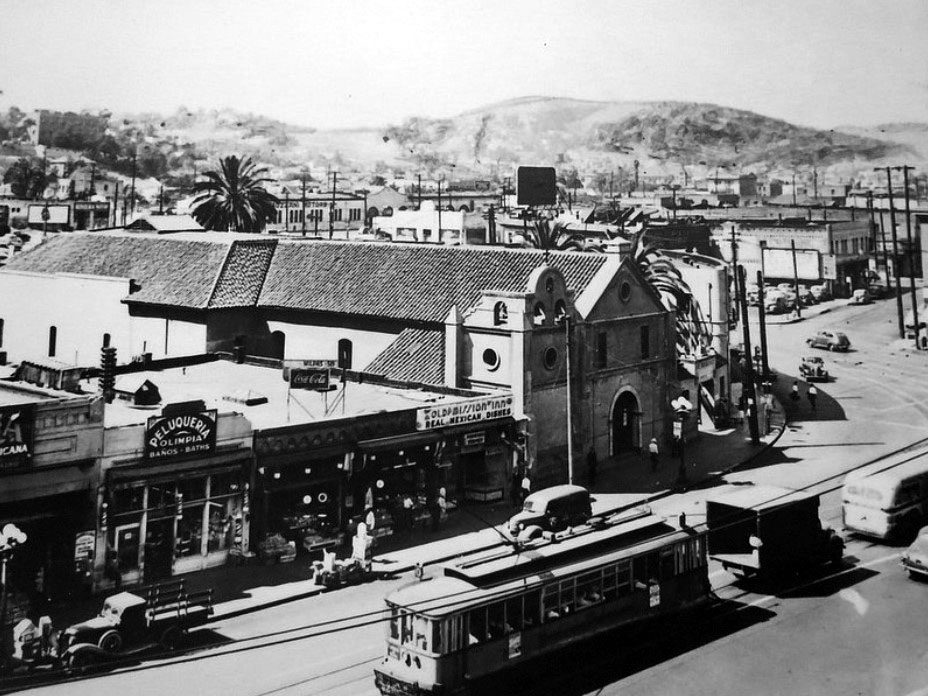

| (ca. 1925)** - The Plaza Church on Main Street across from the Plaza and Olvera Street. Behind the streetcar is the Hotel Pacific, the office of Philip Morici and Co., "Agencia Italiana," and the grocery store of Giovanni Piuma, who also made wine (Piuma Road in Malibu was named for him). The area north of the Plaza was at this time an Italian neighborhood. |

Historical Notes The area’s decline as the center of civic life led to its reclamation by diverse sectors of the city's poor and disenfranchised. The Plaza served as a gateway for newly arrived immigrants, especially Mexicans and Italians. During the 1920s, the pace of Mexican immigration into the United States increased to about 500,000 per year. California became the prime destination for Mexican immigrants, with Los Angeles receiving the largest number of any city in the Southwest. As a result of this dramatic demographic increase, a resurgence of Mexican culture occurred in Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (ca. 1925)* - Exterior view of the Plaza Church from across the street. An elevated LARY booth can be seen on the right edge of the photo. |

Historical Notes Elevated kiosks were used by the Los Angeles Railway and the Yellow Cars (LARY) as a switchman’s tower to control the flow and path of streetcars through intersections. |

|

|

| (1927)** - View of the plaza with several men lounging and sitting under a big tree. The Plaza Church can be seen in the background. To the right of the church is a parochial school. Next to the school is Azteca, a jeweler's that also carries religious artifacts. |

* * * * * |

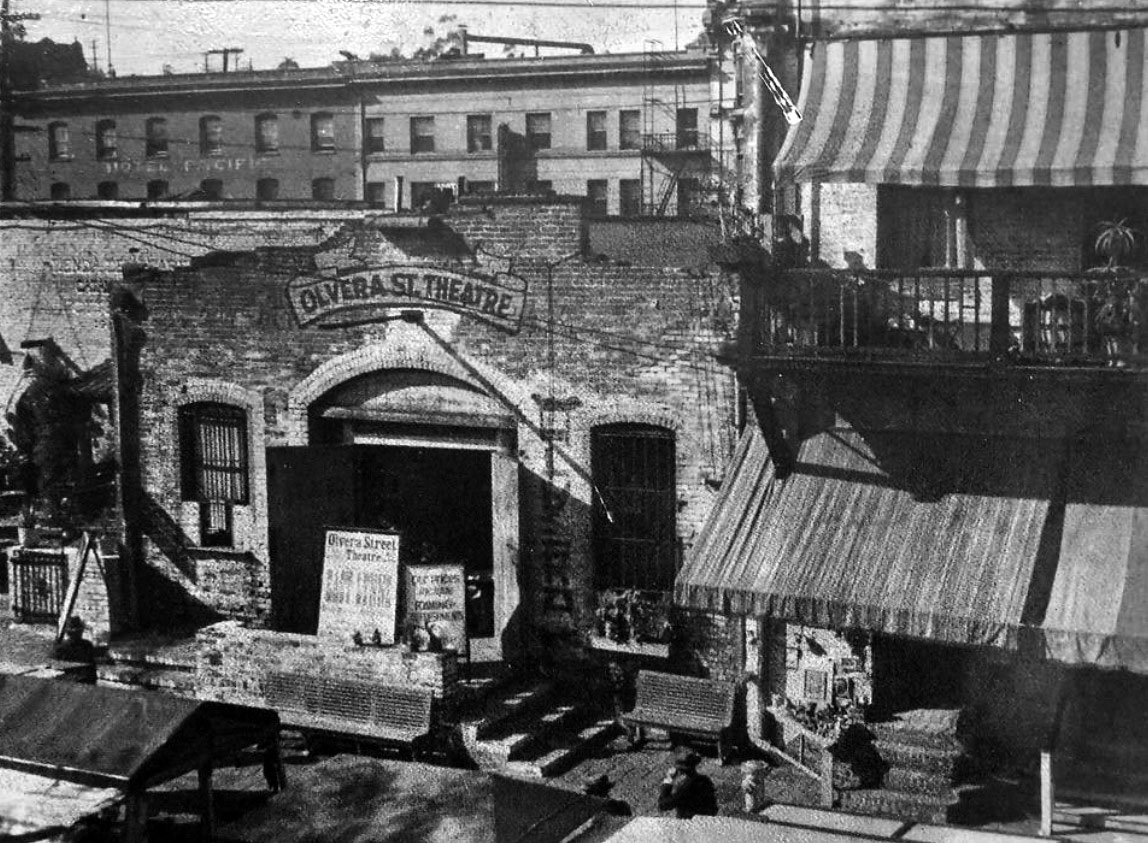

Olvera Street

|

|

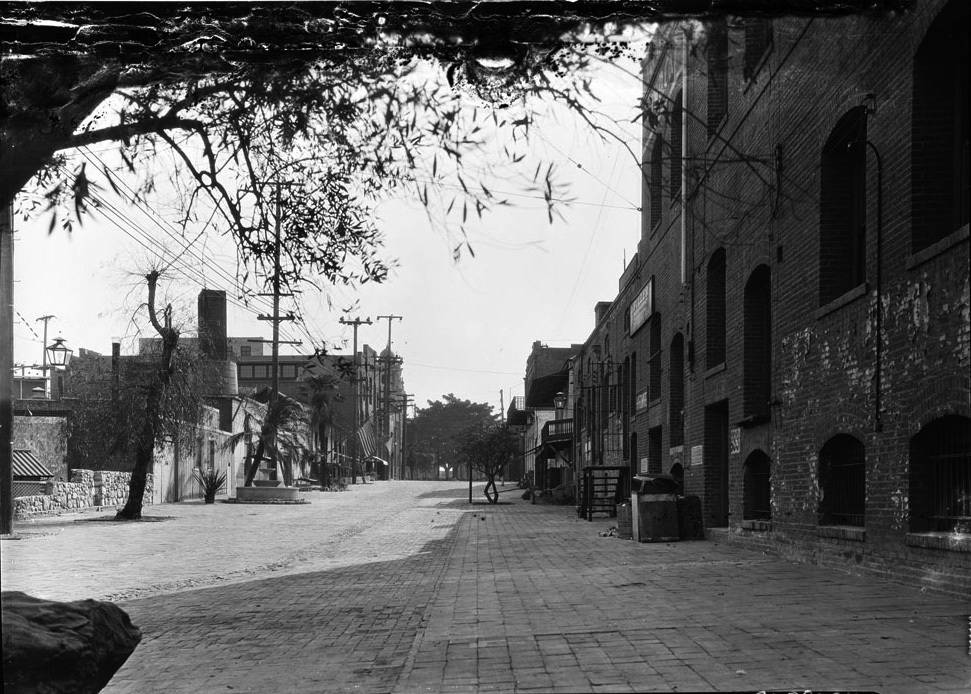

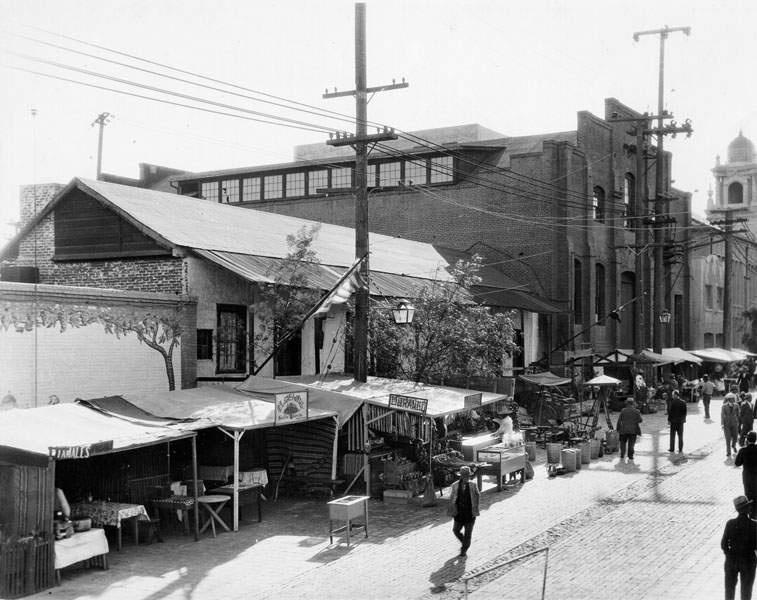

| (1920s)* - Olvera Street looking north, Avila Adobe on right, old cars parked on west side of street, Sepulveda House has large pole in front of it, Tool and Die shop at north end. The above view is what Christine Sterling saw when she decided that something had to be done to bring this historic street back to life. |

Historical Notes Born in Oakland in 1881, Christine Sterling (originally Chastine Rix) migrated south with her husband and two children, residing on Bonnie Brae as early as 1920. In 1926, during a stroll through the rundown alley, Sterling cringed at what had become of the dilapidated Avila Adobe. In an effort to appeal to Anglo hearts and minds, she orchestrated a one-woman campaign to save the old adobe, reminding citizens that the structure had once housed such American luminaries as Commodore Robert F. Stockton, victorious General John C. Fremont, and early explorer Kit Carson. |

|

|

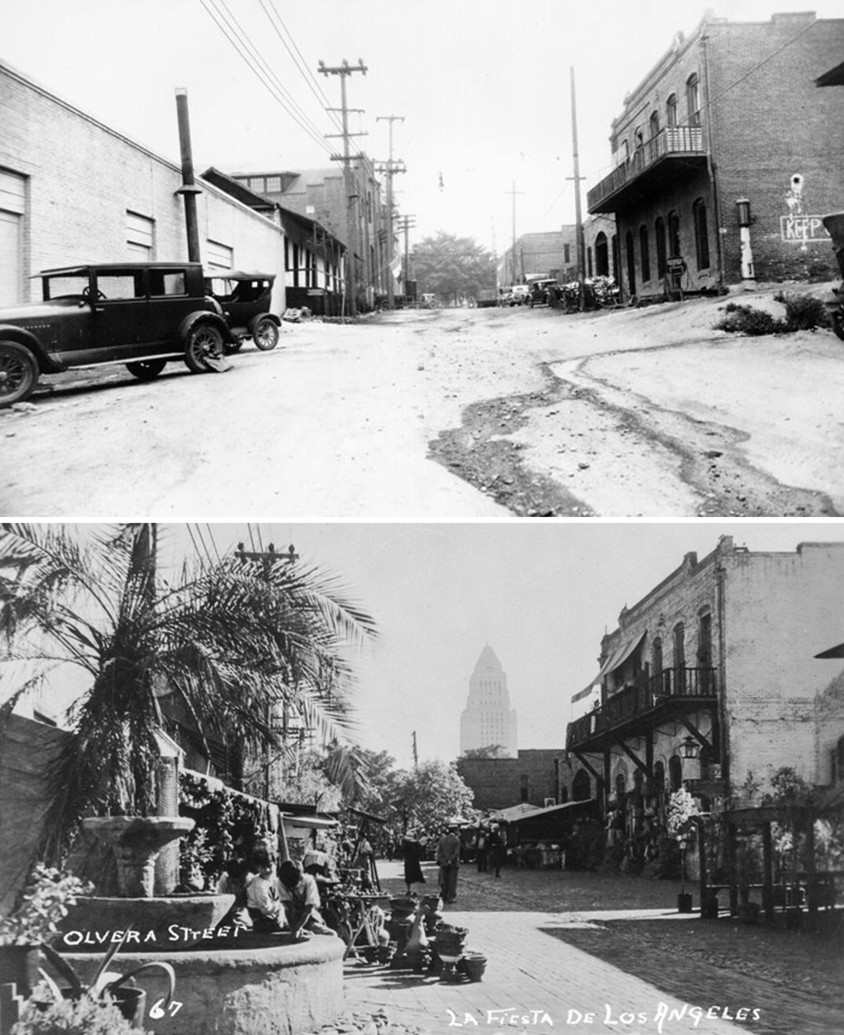

| (1926)* - View looking south on Olvera Street before improvement and also before City Hall was built. On the left the Avila Adobe is seen. To the right is the Sepulveda House with a gas pump on its side. |

Historical Notes The Avila Adobe was built ca. 1818 by Don Francisco Avila, alcalde (mayor) of Los Angeles in 1810. Used as Commodore Robert Stockton's headquarters in 1847, it was repaired by private subscription in 1929-30 when Olvera Street was opened as a Mexican marketplace. It is the oldest existing house in Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1930)* - View of Olvera Street looking south toward the Plaza before vendor kiosks or restaurants were put in place. Later that year things would change. |

Historical Notes Sterling's sales pitch for a Mexican marketplace, replete with vendors and musicians in ethnic garb, persuaded L.A. Times owner Harry Chandler to contribute $5,000 dollars, and in the process several prominent Angelenos joined his philanthropic party. According to the L.A. Times, during a fundraising BBQ held on the porch of the Avila Adobe, the tequila was flowing in spite of prohibition, and then Chief of Police Charlie "Two Guns" Davis was so moved by Sterling's call to action that he volunteered prison labor for Olvera's reconstruction. |

|

|

| (1930)** – View looking south on Olvera Street with City Hall in the background. A man is seen looking at the Avila Adobe. |

Before and After

|

|

| (1926 vs. 1930)* - A 'Before and After' comparison of Olvera Street. By 1930, through the efforts of activist Christine Sterling, the Plaza–Olvera area had been revitalized with the opening of Paseo de Los Angeles—soon popularly known by its official name, Olvera Street. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes In 1930, through the efforts of activist Christine Sterling, the Plaza-Olvera area was revived with the opening of Paseo de Los Angeles (which later became popularly known by its official street name Olvera Street). |

* * * * * |

Olvera Street - 1930s

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1930)** - A view down Olvera Street shortly after its revitalization with building on the left, booths on both sides, and pedestrians strolling through. The two-story building on the left is the Sepulveda House. |

Historical Notes In 1930, through the efforts of activist Christine Sterling, the Plaza-Olvera area was revived with the opening of Paseo de Los Angeles (which later became popularly known by its official street name Olvera Street). Sterling's vision for a "Mexican Marketplace of Yesterday in the City of Today" opened to the public on Easter Sunday in 1930. Her art and design education from Mills College served to inform her Olvera Street project, as well as her next ethnic re-envisioning, China City. Authenticity has always been tinged with historical fantasy in Los Angeles, and for better or for worse, Sterling's efforts indeed saved the Avila Adobe, and in the process created one of L.A.'s most visited tourist attractions. Towards the end of her life, Sterling would suffer the same fate of the shop owners of old Olvera and the displaced denizens of the first Chinatown, after she was evicted from her Chavez Ravine home to make way for Dodger Stadium. Sterling moved in to the Avila Adobe, which would be her final home before she passed on in 1963 at the age of 82. |

|

|

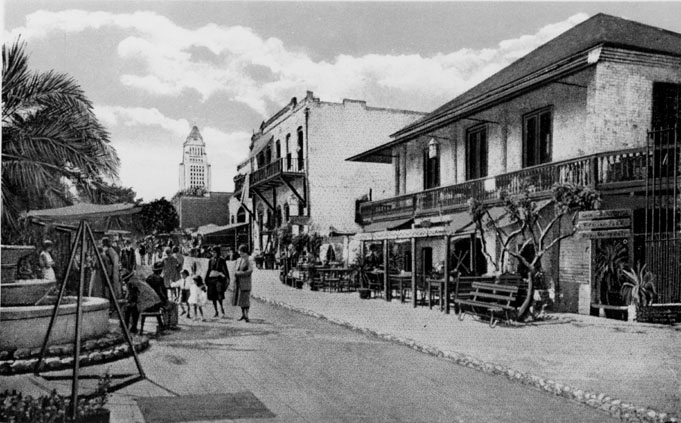

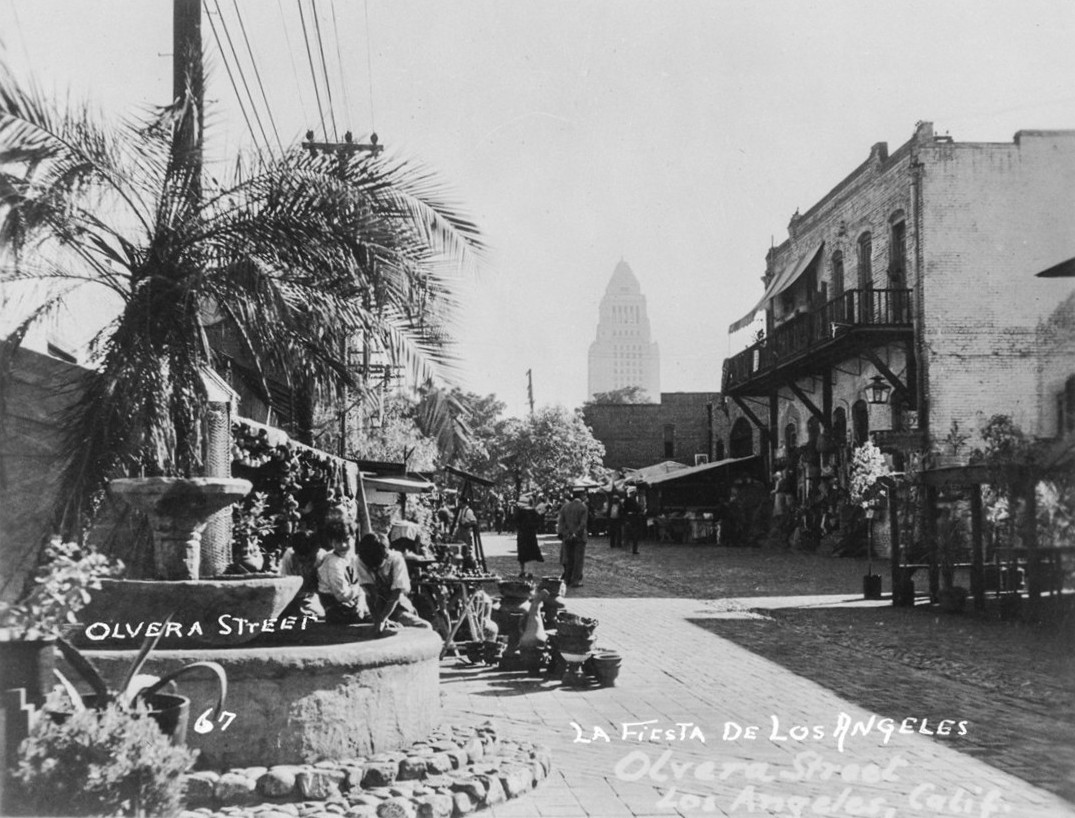

| (ca. 1930)* - Postcard view of Olvera Street looking south with City Hall in background. Pelanconi House and Sepulveda House on right (west) side. Palm tree and fountain on left side (east). |

Historical Notes When it opened in 1930, Olvera Street featured shops and restaurants selling colorful Mexican goods, as well as musicians performing in the outdoor plaza. It was designed to recreate a romanticized version of "Old Los Angeles." The new City Hall was built in 1928. |

|

|

| (1930s)* – View of Olvera Street with vending stands lining the background and three boys sitting on the edge of a fountain in the foreground. Los Angeles City Hall rises in the distance. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes La Fiesta de Los Angeles, first held in 1894, was a citywide celebration that romanticized the region’s Spanish and Mexican heritage through parades, costumes, and music. This spirit carried into the 1930 revitalization of Olvera Street, led by Christine Sterling, who transformed it into a festive marketplace to preserve and promote the city’s Mexican roots. Both the fiesta and Olvera Street reflected Los Angeles’ early efforts to craft a cultural identity that honored its past—though often through a selective, idealized lens. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)** - Late afternoon view of Olvera Street with City Hall in the background. |

Historical Notes Originally unveiled as "El Paseo de Los Angeles" on Easter Sunday in 1930, the street quickly became known as Olvera Street, a name that stuck and is more commonly used today. |

|

|

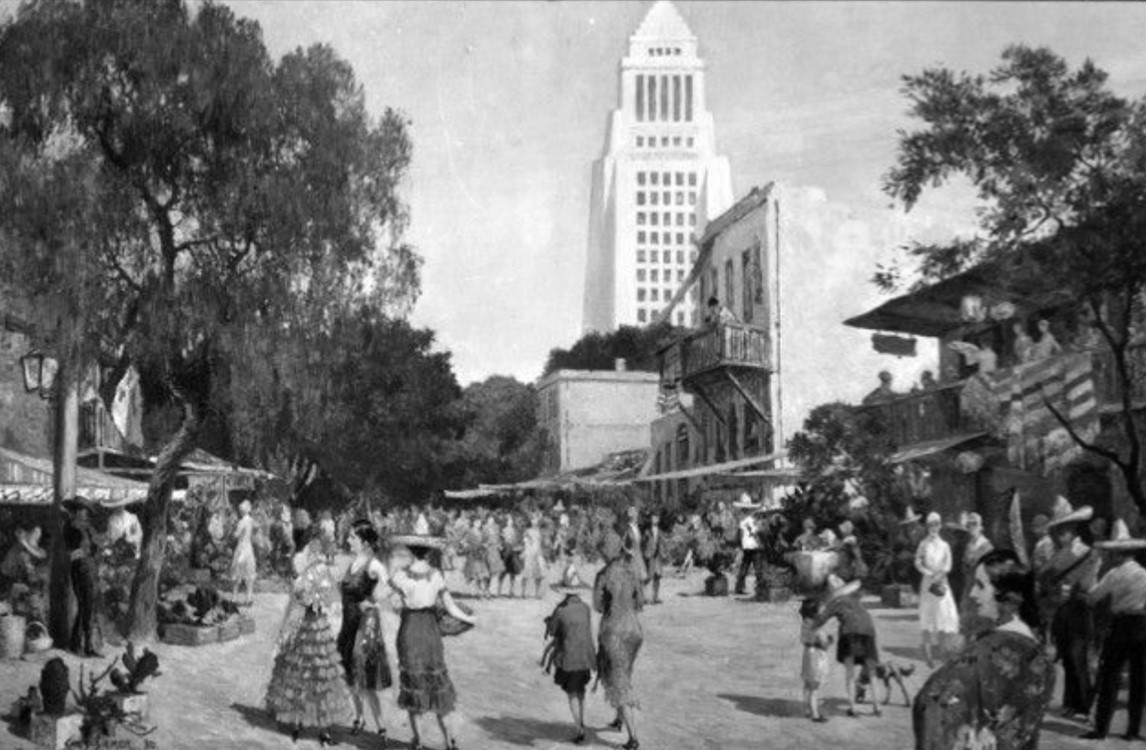

| (ca. 1930)* - A painting by Chris Siemer of Olvera Street, with L.A. City Hall in the background. The painting was created for display for the L.A. Chamber of Commerce. |

Historical Notes As a tourist attraction, Olvera Street is a living museum paying homage to a romantic vision of old Mexico. The exterior facades of the brick buildings enclosing Olvera Street and on the small vendor stands lining its center are colorful piñatas, hanging puppets in white peasant garb, Mexican pottery, serapes, mounted bull horns, oversized sombreros, and a life-size stuffed donkey. Today, Olvera Street attracts almost two million visitors per year. |

|

|

| (1930s)* – A woman leans against a chain barrier in front of a classic automobile, watching a group of Mariachi musicians playing at the edge of Olvera Street, with L. A. City Hall seen in the distance. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes When it opened in 1930, Olvera Street featured shops and restaurants selling colorful Mexican goods, as well as musicians performing in the outdoor plaza. It was designed to recreate a romanticized version of "Old Los Angeles." While it was initially created to cater to a largely Anglo population, over time Olvera Street has become more accepted as a symbolic center of Mexican culture in Los Angeles. |

|

|

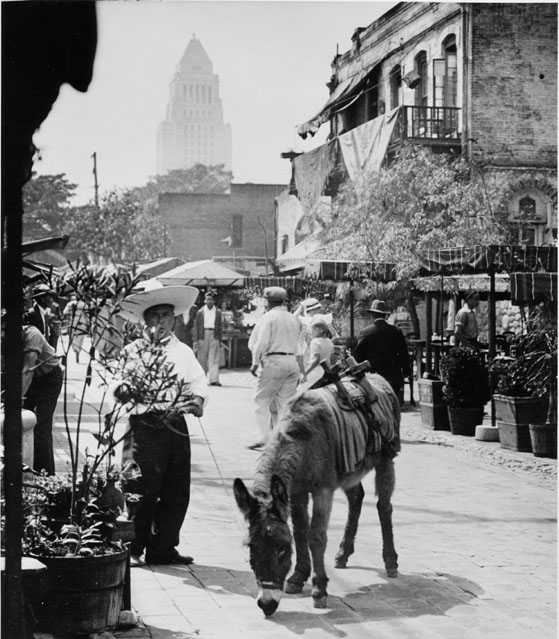

| (1930s)* - Hino Josa leading a donkey. View toward City Hall-looking at Sepulveda House, donkey on Olvera Street. The Sepulveda House fronts both Olvera and Main streets. |

Historical Notes The Sepulveda house was once the private home of one of the most powerful families in early Los Angeles. The Sepulveda House was built by Eloisa Martinez de Sepulveda in 1887, at a time when all predictions were that the population boom of the 1880s would last. However, Señora Sepulveda's hopes for Main Street were not fulfilled and by 1900 the area around her house was mostly industrial. Since the turn of the 20th century, Sepulveda House has been a bordello, a tearoom and the USO canteen during World War II. |

|

|

| (1930s)* - Interior view of the Sepulveda House showing wooden floors and staircase. |

* * * * * |

El Paseo de Los Angeles

|

|

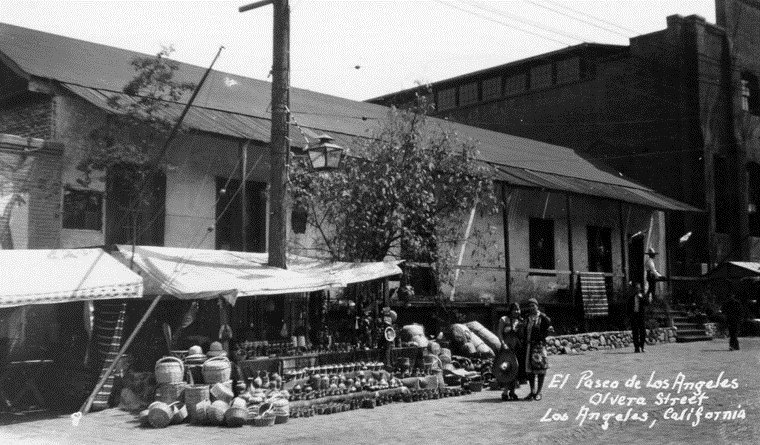

| (1930s)* – Postcard view of El Paso de Los Angeles "The Pathway of the Angels", Olvera Street, Los Angeles, CA. |

Historical Notes Originally unveiled as "Paseo de Los Angeles" on Easter Sunday in 1930, the street quickly became known as Olvera Street, a name that stuck and is more commonly used today. This historic area, envisioned by Christine Sterling as a vibrant Mexican marketplace and cultural center, is now part of the larger El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument. It represents the birthplace of Los Angeles and serves as a colorful tribute to the city's Mexican heritage. Olvera Street continues to draw millions of visitors annually with its array of shops, restaurants, and cultural events, offering a unique glimpse into the rich history and diverse culture of Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1930s)* – A man playing the guitar serenades a young woman in front of an adobe on Olvera Street. Both are dressed in traditional Mexican clothing. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes After Olvera Street first opened in 1930, it quickly became a vibrant cultural and tourist attraction, celebrating the Mexican heritage of Los Angeles. Vendors and performers, often dressed in traditional Mexican clothing such as serapes, rebozos, and charro outfits, helped create an authentic atmosphere. Spearheaded by Christine Sterling, the street was transformed into a Mexican-style marketplace, evoking the early pueblo days of the city. This romanticized vision of Mexican culture became a significant draw for both locals and tourists, preserving the area’s historic charm while promoting Mexican traditions in the heart of Los Angeles. |

|

|

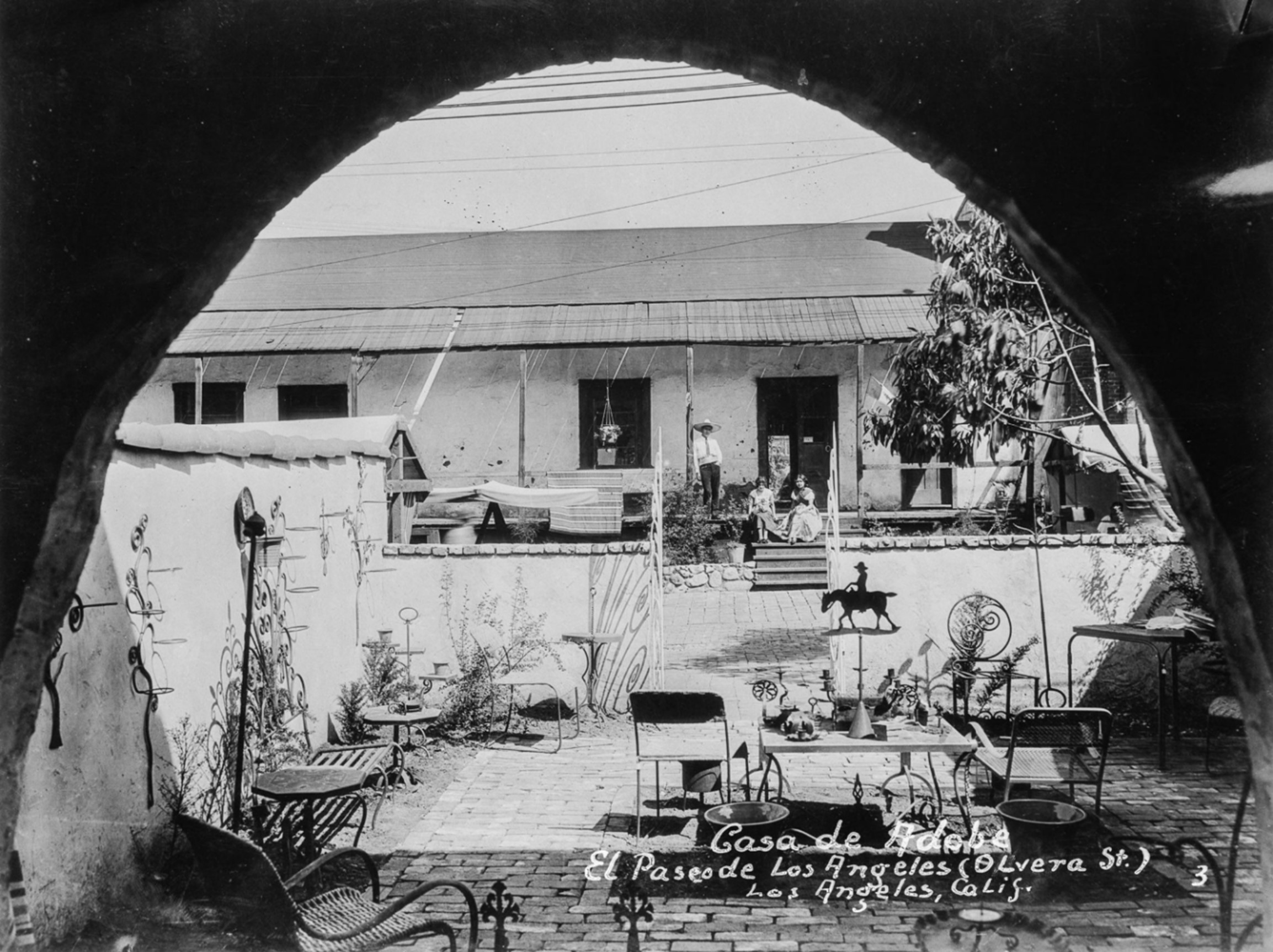

| (1930s)* – Looking through an archway across a courtyard showing a man and two women on the porch of the Avila Adobe on El Paseo de Los Angeles. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes Located at 10 Olvera Street, the Avila Adobe was built in 1818 by Francisco Ávila, a prominent cattle rancher and early mayor of Los Angeles. It is recognized as the oldest standing adobe house in the city. Click HERE to see more early views of the Avila Adobe. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)** - A view of Olvera Street looking across at vending booths in front of the Avila Adobe with two pedestrians walking near. |

Historical Notes In 1930, through the efforts of activist Christine Sterling, the Plaza-Olvera area was revived with the opening of Paseo de Los Angeles (which later became popularly known by its official street name Olvera Street). |

|

|

| (1930s)^ - View of three women dressed up in traditional Mexican/Spanish clothing posing for the camera in front of a fountain on Olvera Street. Socialite and preservationist, Christine Sterling led efforts to preserve the historic plaza and its buildings. |

Historical Notes Current historians note that the original intention of Olvera Street was to focus on LA’s Spanish past instead of its Mexican/Indigenous one. William Estrada, author of “The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space,” writes: "Olvera Street was successful and even surpassed Mexican tourist zones along border in Tijuana & Mexicali because it fulfilled tourists’ preconceived notions about Mexico & quaintness of its culture without risk or ‘reality’ of actually crossing border." |

|

|

| (1939)* – Postcard view showing two merchants having a conversation on Olvera Street in front of a vending booth with sign that reads: El Balero |

Historical Notes In its early days Olvera Street catered to a largely Anglo population; however, the meaning of Olvera Street has changed over the years, and the delusional fabrication has now been largely accepted as the symbolic epicenter of Mexican culture. |

* * * * * |

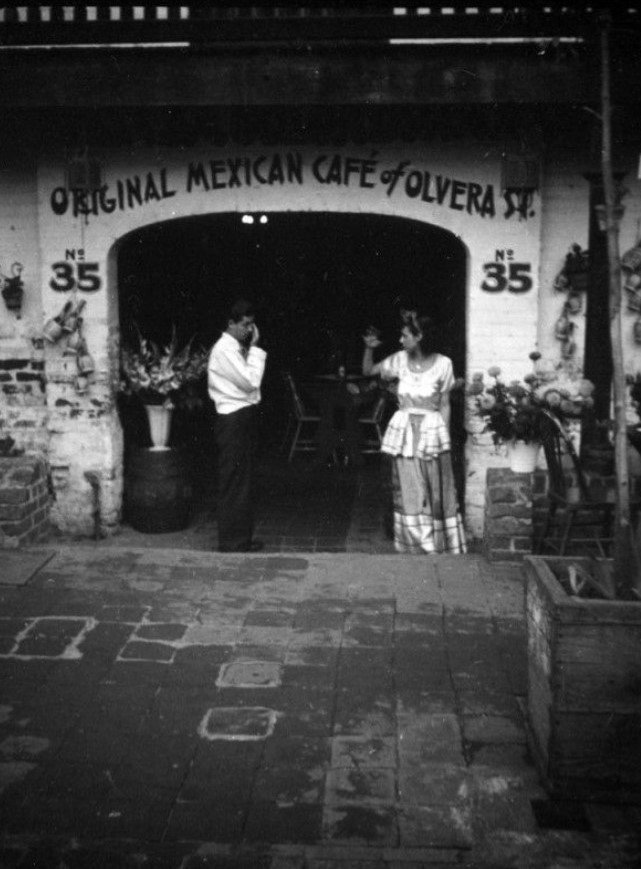

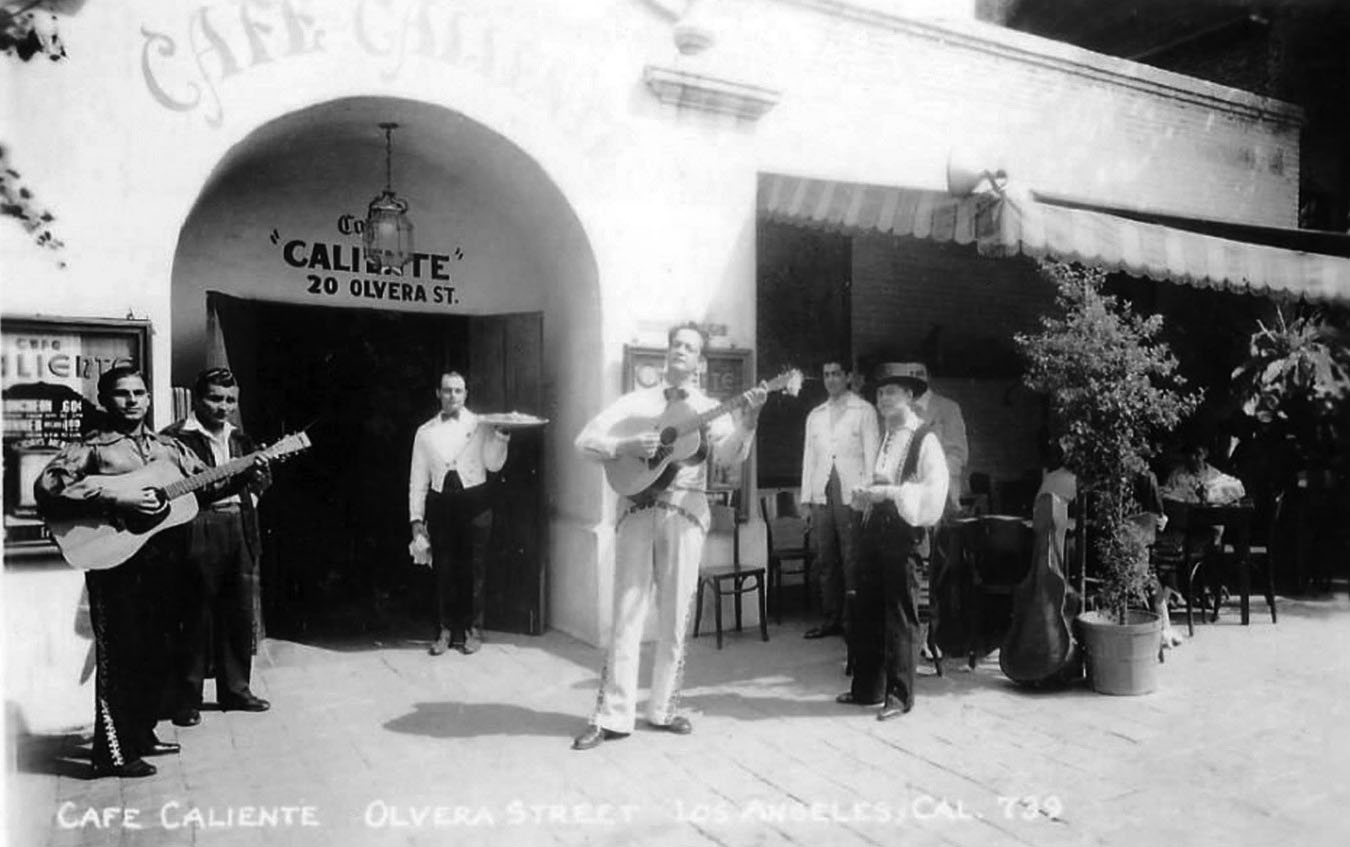

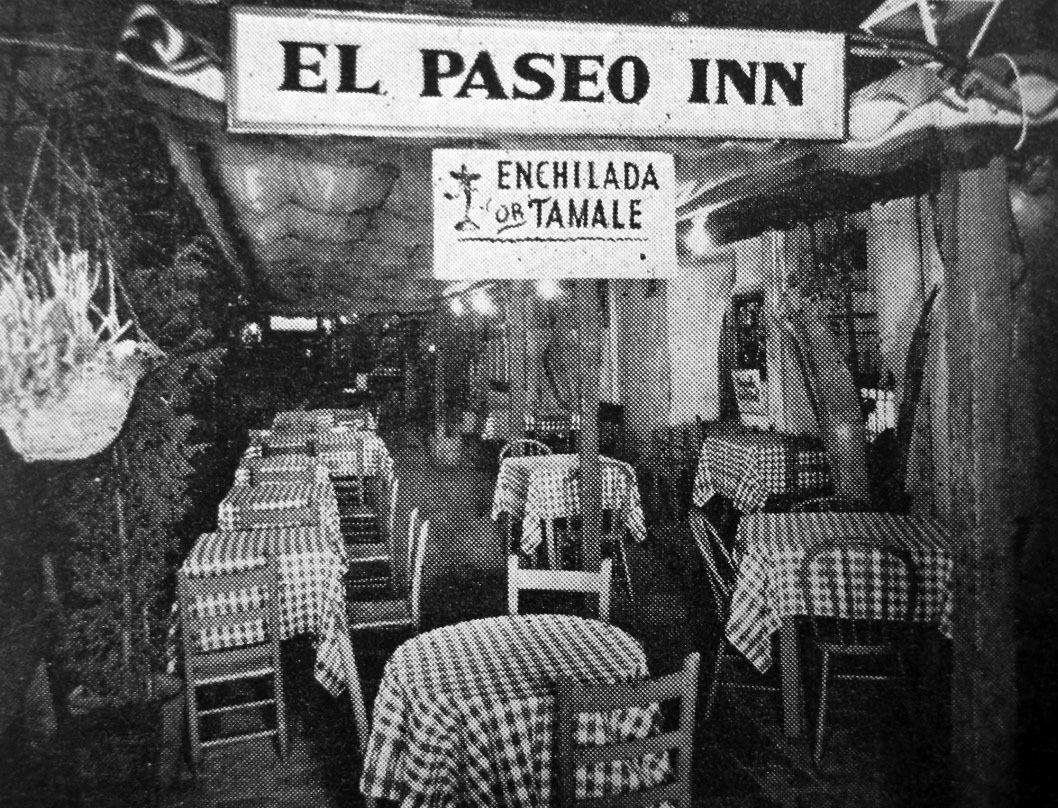

Original Mexican Cafe of Olvera Street

|

|

| (ca. 1937)* - The Original Mexican Café of Olvera Street, at No. 35, Olvera Street. Photo by Herman Schultheis |

* * * * * |

Garnier Block

|

|

| (1924)* - Aerial view of the Los Angeles Plaza and surrounding buildings, with the Garnier Block highlighted in upper right. Annotated by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes Nearly half of the buildings to the right of the Plaza (south of the Plaza) were demolished in the 1950s to make way for the Hollywood Freeway. Similarly, the buildings in the upper left were demolished in the late 1930s to make way for Union Station. |

|

|

| (ca. 1928)* - View looking south on Main Street showing the newly constructed City Hall standing in the background (corner of Temple and Main streets) with the Brunswig Building and Old Plaza Church at right. |

|

|

| (2021)* - Contemporary view looking south on Main Street from in front of the Los Angeles Plaza, with the Old Plaza Church visible on the right. Notable buildings from left to right include the Pico House, City Hall East, City Hall, the Federal Courthouse, the Vickrey/Brunswig Building, and the Plaza House. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1928 vs. 2021)* – Looking south on Main Street from in front of the Los Angeles Plaza, with the Old Plaza Church visible on the right. Most of the buildings seen in the 1928 photo still stand today. The only additions visible in the contemporary photo are the Federal Courthouse (1940) and City Hall East (1969). Photo comarison by Jack Feldman. |

* * * * * |

Garnier Block

|

|

| (ca. 1937)* - View looking southwest across Los Angeles Street showing the Garnier Block with the Jennett Block on the left and City Hall in the background. Photo by Herman Schultheis. |

Historical Notes Built in 1890 by Philippe Garnier—a French settler and prominent businessman—the Garnier Building is the oldest and most important single structure linking the Chinese community to Los Angeles’ original Chinatown. It is also the oldest and most significant Chinese building in a major metropolitan area of the state, as the original buildings in San Francisco’s Chinatown were destroyed by the earthquake of 1906. The southern wing of the Garnier Building was razed in the 1950s along with the Jennette Block to accommodate the construction of the Hollywood Freeway (101). |

|

|

| (1942)* – View of the west side of Los Angeles Street between Arcadia Street and the Plaza, showing both the Garnier Block and Jennette Block with the newly built Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office Building in the background. |

Historical Notes The Garnier Block was a pivotal structure in Los Angeles' original Chinatown during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Located at 415 N. Los Angeles Street near the LA Plaza, it served as a vital hub for the Chinese community, housing various shops, schools, temples, and businesses. The building was not only a commercial center but also an important social venue where community events, dances, and theatrical performances took place. |

|

|

| (2022)* - Google Street View showing the Garnier Block as it looks today. |

Historical Notes The southern wing of the Garnier Building was razed in the 1950s along with the Jennette Block to accommodate the construction of the Hollywood Freeway (101). |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1937 vs 2022)* - A view of the west side of Los Angeles Street, where the Garnier Block still stands today. The construction of the Hollywood Freeway (#101) removed everything to the left (south) of the Garnier Building, including an area once known as the Jennette Block. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes As plans for Union Station progressed in the 1930s, much of Chinatown faced demolition and displacement. However, the Garnier Block remarkably survived these changes, becoming a symbol of resilience for the community. Today, it stands as the oldest surviving building from LA's historic Chinatown and remains a significant landmark representing the rich cultural heritage of Chinese Americans in California. |

* * * * * |

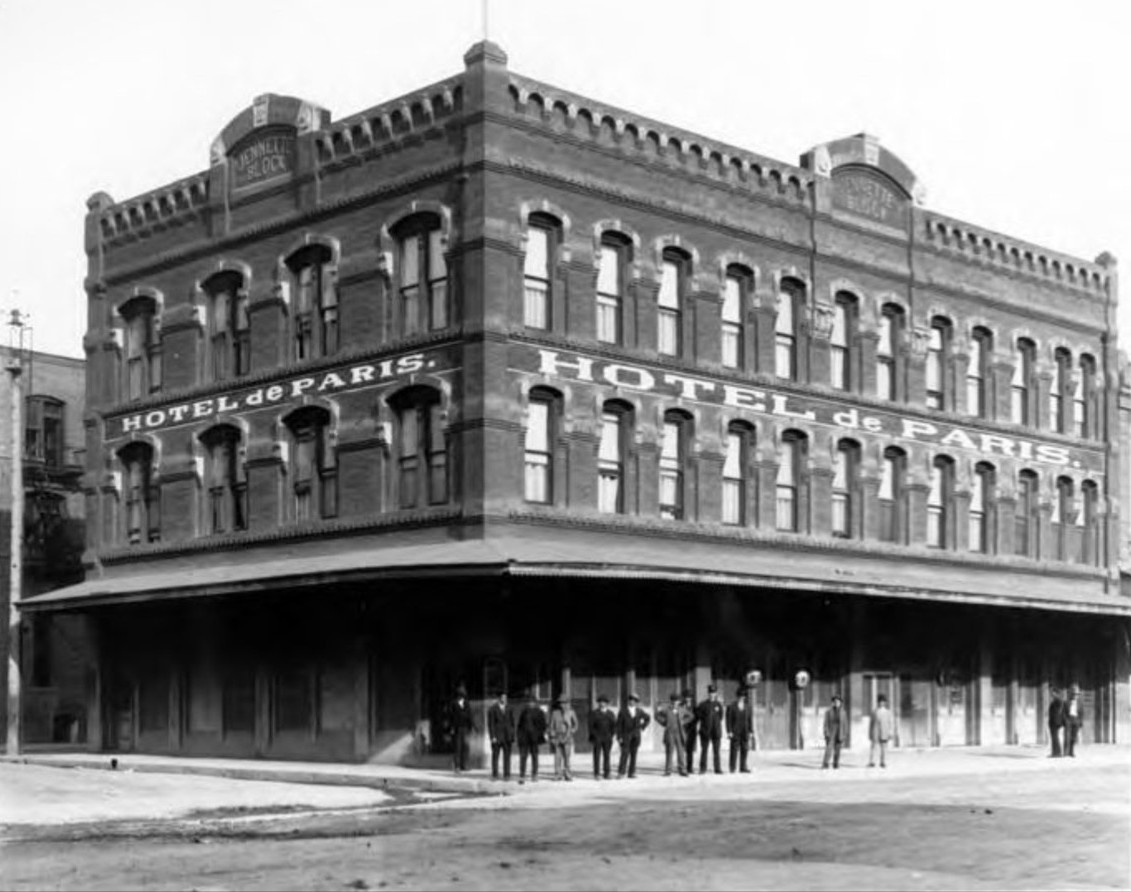

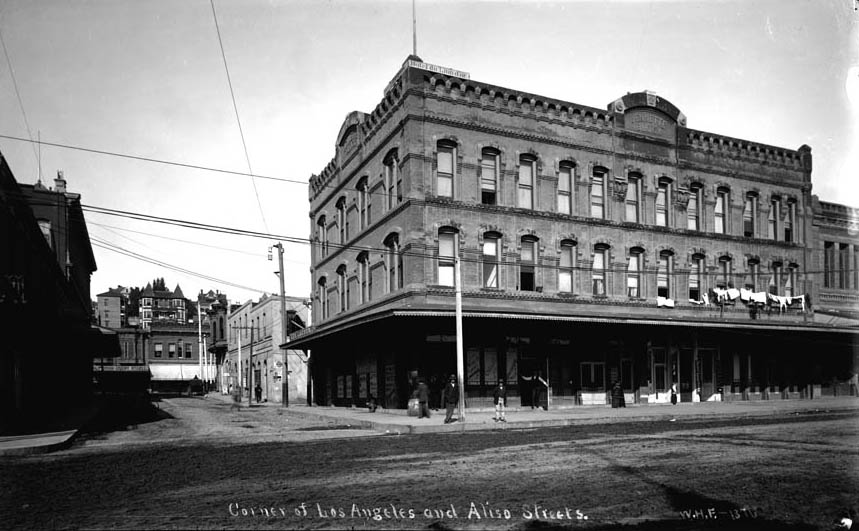

Jennette Block

|

|

| (1890)* – A view of the northwest corner of Los Angeles and Arcadia Streets, where the Hotel de Paris was the primary occupant of the Jennette Block. |

Historical Notes The Jennette Block, constructed circa 1888, was a prominent three-story brick commercial building that quickly became a focal point of downtown Los Angeles. The Hotel de Paris, occupying its upper floors, served as a vital hub for French-owned businesses and travelers, making the Jennette Block a central gathering place for the city's French community. The building was part of the diverse urban fabric that defined early Los Angeles, where immigrant populations, including French, Chinese, and others, lived and worked in close proximity. The structure’s Italianate architectural style—with its arched windows, decorative cornice, and ground-floor canopy—was typical of the commercial buildings that shaped the growing city during its transition from a pueblo to a major metropolis. |

|

|

| (ca. 1895)* - Looking west on Aracadia Street toward Fort Hill from Los Angeles Street with the Jennette Block standing on the northwest corner. |

Historical Notes Aliso Street changed names to Arcadia Street west of Los Angeles Street. See map below. |

|

|

| (ca. 1925)* - On the left is the Jennette Block on the northwest corner of Arcadia and Los Angeles Streets, and on the right is the Garnier Building at 415 North Los Angeles Street. The construction of the #101 Freeway took away the Jennette Block and left the Garnier Building. The Jennette Block was built circa 1888 and the Garnier Building in 1890. |

Historical Notes By the mid-1920s, the Jennette Block was well-established as a cornerstone of Old Chinatown’s commercial district. The building’s tenants included the Hotel de Paris and a mix of shops, restaurants, and service businesses that catered to the multicultural community of the area. The Jennette Block was known for its lively street presence and its role in bridging various immigrant communities, including French, Chinese, and other downtown residents. The surrounding area reflected the cosmopolitan energy of Los Angeles at the time, filled with hotels, markets, and cultural landmarks. The 101 Freeway’s construction in the 1950s led to the demolition of the Jennette Block and significantly altered the street grid, erasing much of the neighborhood’s original character while the adjacent Garnier Building, though partially reduced, survived and remains an important remnant of the city's early history. |

|

|

| (2023)* - Looking across Los Angeles Street toward the former site of the Jennette Block, now replaced by the overcrossing of the 101 Freeway and the realigned Arcadia Street, which now serves as a frontage road. The northern portion of the Garnier Building still stands on the northwest corner, a surviving piece of Los Angeles’ early Chinatown. |

Historical Notes The modern scene reflects the profound changes brought by mid-20th-century urban development. The site where the Jennette Block once stood is now dominated by the Hollywood Freeway overpass and a realigned Arcadia Street, now functioning as a freeway frontage road. This realignment and the freeway’s construction erased not only the Jennette Block but also a portion of Los Angeles’ original Chinatown. The northern part of the Garnier Building, visible in the image, remains as a rare survivor and now houses the Chinese American Museum within El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument. While the Jennette Block has vanished from the physical landscape, it endures through photographs and historical documentation as a symbol of the diverse immigrant communities that once thrived in the area. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1925 vs. 2023)* – A ‘Then and Now’ Comparison of the Jennette Block and Garnier Building. Looking north across Los Angeles Street, the 1925 image shows the Jennette Block (left) on the northwest corner of Arcadia and Los Angeles Streets, with the Garnier Building (right) extending along Los Angeles Street. By 2023, the Jennette Block and the original stretch of Arcadia Street were removed to make way for the 101 Freeway. The street now visible is a realigned frontage road that retains the Arcadia Street name. The northern portion of the Garnier Building still stands today as part of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, serving as a rare remnant of the city’s early Chinatown. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes This ‘Then and Now’ comparison captures the dramatic transformation of the area over nearly a century. The Jennette Block once played a vital role in the city’s commercial and cultural life, housing the Hotel de Paris and serving as a crossroads for French, Chinese, and other immigrant communities in Old Chinatown. The building’s demolition in the 1950s for the construction of the Hollywood Freeway not only erased a key architectural landmark but also disrupted the surrounding neighborhood and displaced much of the local community. The realigned Arcadia Street, now serving as a frontage road, bears little resemblance to the vibrant streetscape that once existed here. The Garnier Building’s survival offers a tangible link to the past, standing as a testament to the layered history of Los Angeles and the diverse communities that helped shape it. |

* * * * * |

Ferguson Alley

|

|

| (1921)* - This detail from a Baist’s Real Estate Atlas survey map highlights Ferguson Alley, a narrow passage running between Alameda Street and the southeast corner of the Plaza. It also shows the remaining section of Calle de los Negros, labeled as N. Los Angeles Street, where it terminated. |

Historical Notes Ferguson Alley was a narrow thoroughfare in early Los Angeles, located in the city's first Chinatown near the Plaza area. Named after William Ferguson, the alley was a densely populated space that reflected the city's ethnic diversity, housing Chinese residents and businesses alongside other immigrant communities. On October 24, 1871, Ferguson Alley and the surrounding area became the site of one of the darkest events in Los Angeles history. A mob of approximately 500 white and Latino Americans attacked the Chinese community, resulting in the deaths of at least 17 Chinese residents. This massacre, one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history, began after a conflict between rival Chinese tongs led to the death of a white rancher. |

|

|

| (1924)* - Aerial view of the Los Angeles Plaza and surrounding area showing the Ferguson Alley at center top. Annotated by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes Ferguson Alley was a narrow thoroughfare in early Los Angeles, named after William Ferguson, an Arkansas native who settled in the city in 1869. It was located near the Plaza, running between Los Angeles Street and Alameda Street. The alley was officially established around 1890, with Ferguson deeding it to the city in 1892. |

|

|

| (1925)* - Looking at the east side of Los Angeles Street at its intersection with Fergusion Alley see on the left next to the two power poles. |

Historical Notes Old Chinatown, including Ferguson Alley, reached its peak between 1890 and 1910, expanding to about fifteen streets and alleys with around two hundred buildings. However, the area began to decline in the early 1910s due to several factors: negative public perception influenced by gambling houses and opium dens, tong warfare that deterred business, the status of residents as tenants rather than property owners, and the threat of redevelopment that led to neglect in building maintenance. These issues contributed to a downward spiral, with landlords increasingly disinterested in improving their properties and residents facing deteriorating conditions while remaining reluctant to leave. |

|

|

| (1925)* - The Plaza Service Station located on the east side of Los Angeles Street in old Chinatown with Ferguson Alley at the far left. This is a blow up view of the previous image. |

|

|

| (1933)* - Looking east down Ferguson Alley from Los Angeles Street in old Chinatown. One-story brick buildings line the narrow alley at left, while two-story buildings can be seen at right. Most of the doorways have metal gates over the openings, suggesting that they are closed. A balcony can be seen on the second story of a building in the foreground at right. An automobile can be seen at left, near a sign that reads "Jerry's 'Where folks eat'". |

Historical Notes Jerry's Joynt was a restaurant located at 211 Ferguson Alley near the Plaza in Los Angeles' Old Chinatown during the early 1900s. It was considered one of the better dining establishments in the area, offering moderate prices and good food. The restaurant featured a jade lounge with carved woodwork and handsome figurines, making it an interesting spot to visit even for those not looking to dine. |

|

|

| (1934)* – Sketch of Los Angeles Street and Ferguson Alley in Old Chinatown.. |

Historical Notes In the early 20th century, Ferguson Alley remained central to Chinatown's development, reflecting the area's resilience despite challenges like forced relocations due to Union Station's construction. |

|

|

| (ca 1938)* - Close up view looking east on Ferguson Alley at Los Angeles Street in Chinatown. |

Historical Notes In the 1930s, plans for the construction of Union Station led to the gradual demolition of Old Chinatown. A remnant of the original Chinatown, including Ferguson Alley, persisted into the early 1950s. During this time, several businesses and a Buddhist temple lined Ferguson Alley, which was described as a narrow one-block street running between the Plaza and Alameda. |

|

|

| (1938)* – Four children and two men pose for the camera in Old Chinatown at the entrance to Ferguson Alley with a sign for Jerry's Joynt on the wall in the background. |

Historical Notes Christine Sterling, known for her work on the Olvera Street and China City projects, advocated for the razing of all remaining structures between the Plaza and Union Station, including those along Ferguson Alley. This ultimately led to the complete demolition of the area, marking the end of Ferguson Alley's history near the LA Plaza. Today, the only remaining edifice from the original Chinatown is the two-story Garnier Building, which now houses the Chinese American Museum. |

|

|

| (1948)* - Looking south on Los Angeles Street from the corner of Ferguson Alley toward City Hall with the Garnier Block seen across the street. Photo by Arnold Hylen. |

Historical Notes Today, no physical trace of Ferguson Alley remains. The only surviving edifice from the original Chinatown is the two-story Garnier Building, which now houses the Chinese American Museum. The demolition of Ferguson Alley and the surrounding area marked the end of Old Chinatown and paved the way for the modern urban landscape of downtown Los Angeles. |

Then and Now (Hybrid)

|

|

| (1924 vs. 2024)* – A blended view of the Los Angeles Plaza and its surrounding area. Notice the 101 Freeway on the right and the on-ramp now occupying the former entrance to the historic Ferguson Alley. Annotated by Jack Feldman. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1924 vs. 2024)* – Aerial view over the Los Angeles Plaza showcasing the dramatic transformation of Old Chinatown (upper half of the photo) over a century. The area is now home to Union Station and part of the 101 Freeway. Notably, the historic intersection of Ferguson Alley and Los Angeles Street has become the on-ramp to the Hollywood Freeway. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

* * * * * |

LA Plaza

|

|

| (1930)** - A man stands on a soapbox in front of a crowd of men gathered at the Los Angeles Plaza. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)** - People are seen sitting on benches and relaxing in the shade of a large rubber tree in the Plaza. To the left is seen the Pico House. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1930)* - Shoeshine in the LA Plaza with the Pico House seen in the background. |

* * * * * |

Avila Adobe

|

|

| (1932)* - View of the Avila Adobe house on Olvera Street, taken in 1932 - two years after Olvera Street was converted to a colorful Mexican marketplace - as made evident by the small vendor stands visible throughout. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1935)** - Avila Adobe as seen from a building across Olvera Street. In front of the house is a wooden cart, and a Mexican flag is by the entrance. It is located at 14-16-18 Olvera Street and was used by the Avila and Rimpau families. |

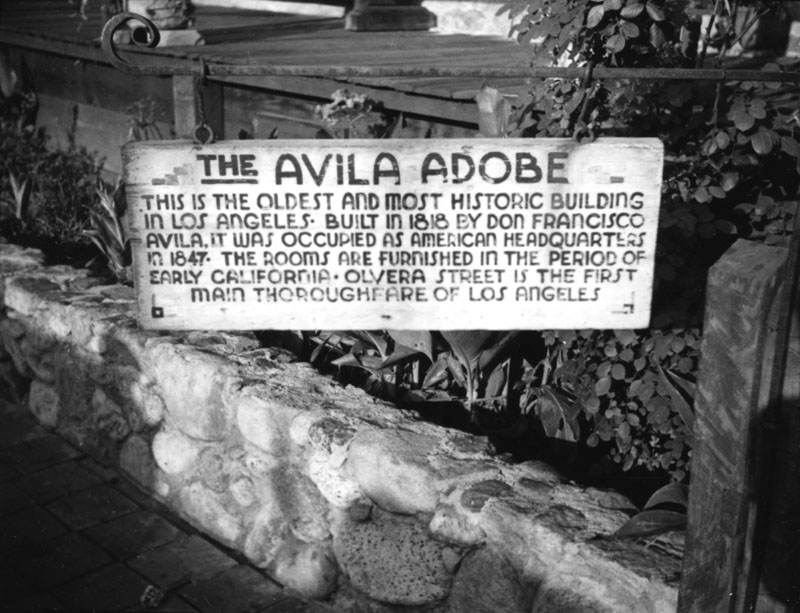

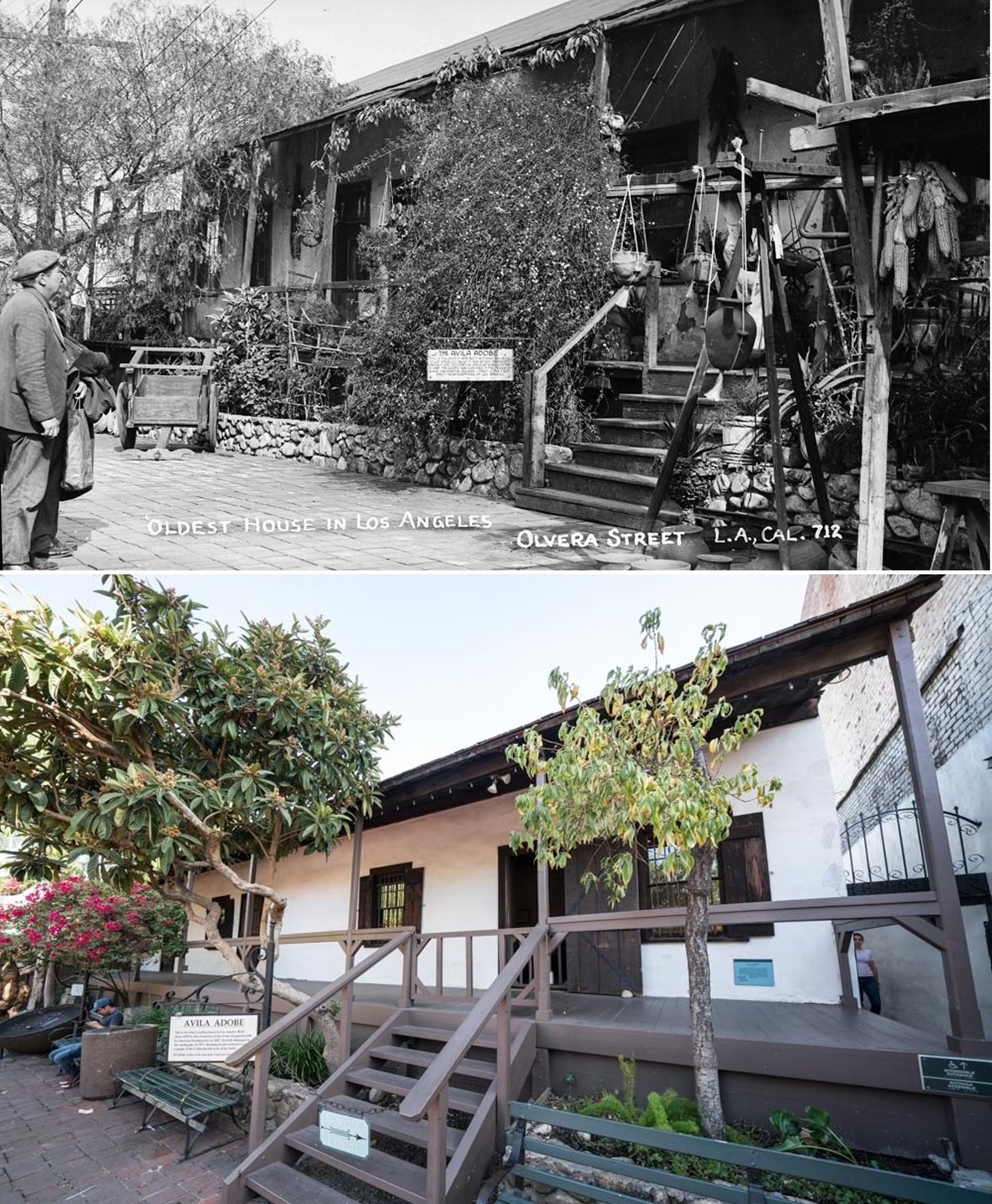

Historical Notes The Avila Adobe, presently the oldest existing residence within the city limits, was one of the first town houses to share street frontage in the new Pueblo de Los Angeles. The original structure was nearly twice as long as it is now, and was L-shaped with a wing that extended nearly to the center of Olvera Street, which was the town's plaza.** The Avila Adobe is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is also listed as California State Landmark No. 145 (Click HERE to see more in California Historical Landmarks in LA.) |

|

|

| (1930s)#+ – Postcard view showing the Avila Adobe on Olvera Street. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)**- View of the sign in front of the Avila Adobe, the oldest existing residence within the city limits. |

Historical Notes In 1847, this adobe became the temporary headquarters for Commodore Robert Field Stockton and General Stephen Watts Kearny during the American occupation of Los Angeles. At that time, it was the permanent home of Doña Maria Encarnación Avila - widow of Don Francisco Avila. When the townspeople got word that American troops were rapidly approaching the pueblo, many of them evacuated their homes to seek refuge at outlying ranchos. Doña Encarnación was among those that fled their adobes. At which point, Commodore Stockton's men seized the adobe for their commanding officer. When the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed a few days later, Stockton abandoned the adobe and Doña Maria Encarnación returned to her beloved home, where she remained until her death in 1855.** |

|

|

| (1930s)** - View of the Avila Adobe house on Olvera Street, showing the rear of the home. Several windows and doorways are visible under the long, covered "corredor" (or porch); steps lead down to a lower area of the courtyard. |

Historical Notes The Avila Adobe consisted of a generous courtyard with covered porches for each of the garaging areas, stables, workshops, etc., as well as a garden and vineyard, which Don Francisco tended to regularly.** |

|

|

| (ca. 1930s)** - An Avila Adobe room - possibly a sitting room or living room. The focal point of the room is a well-used and smoke-stained fireplace along the back wall; a wooden shelf rests along the length of the wall, displaying pots, pans, plates, and knick-knacks. Several different types and styles of chairs are located around the area, and a small table with a tablecloth is visible on the left. |

Historical Notes In 1953, the State of California acquired the Avila Adobe as part of El Pueblo de Los Angeles State Historic Park, and has been opened to tours since 1976.** |

|

|

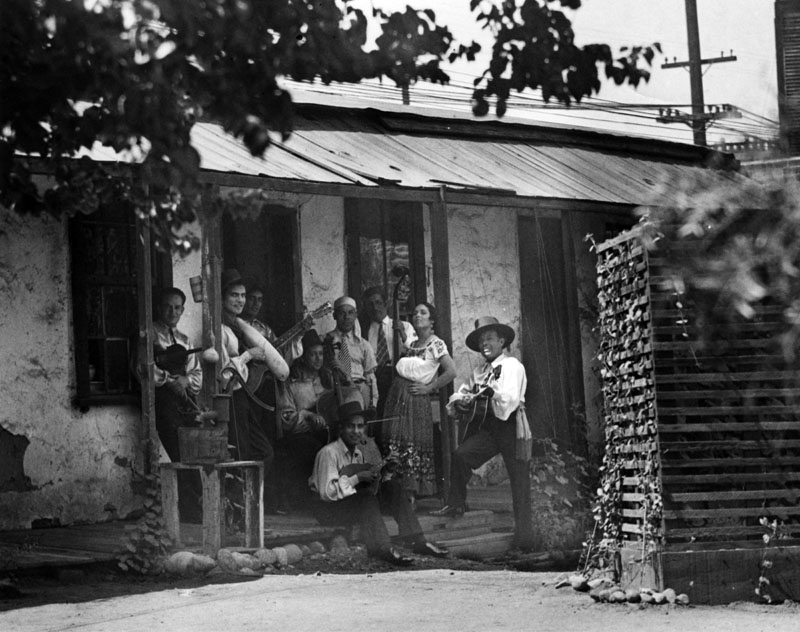

| (ca. 1930s)* - Group of musicians and dancers pose in the central courtyard of the Avila Adobe. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1948 vs. 2020)* - Avila Adobe, the oldest existing residence within the city limits. |

Historical Notes Avila adobe holds the record for being the oldest house in Los Angeles. It was built in 1818 by Francisco Avila. It's protected by the Los Angeles Plaza Historic District & California State Historic Park. The walls of the Avila Adobe are 2.5–3 feet thick and are built from sunbaked adobe bricks.* |

* * * * * |

|

|

| (1934)** - The Pico House, sometimes called "Old Pico House", built by Pio Pico in 1869-70. Seen from across the street, "Old Pico House" is on top of the building, and at street level a sign for "Pico House Cafe" is painted on the right side corner of the building. There is an open door in the middle of the block and a closed door farther to the left. One car is parked in front and several people are standing or walking in the area. |

Historical Notes In 1868, Pío de Jesús Pico constructed the three story, 33-room hotel, Pico House (Casa de Pico) on the old plaza of Los Angeles, opposite today's Olvera Street. At the time of its opening in 1869, it was the most lavish hotel in Southern California. Even before 1900, however, it began a slow decline along with the surrounding neighborhood, as the business center moved further south. After decades of serving as a shabby flop house, it was deeded to the State of California in 1953, and is now a part of El Pueblo de Los Angeles State Historic Monument. It is used on occasion for exhibits and special events.^* |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)** – View looking north showing the La Plaza (United) Methodist Church, Plaza Community Center, and the Methodist Headquarters Building, with a portion of the Plaza in the foreground. |

Historical Notes The Church is located on the site of the Tapia/Olvera adobe, which served as an early service building for the United Methodist Church mission in Los Angeles. The Methodist Church was also the founding agent in Southern California for Goodwill Industries. The adobe was torn down in 1917 and, nine years later, architects Train and Williams completed this Churrigeresque-style church. ^#^ |

|

|

| (1936)^*# - View of the Plaza as seen from the roof of the Brunswig Building. The Plaza Methodist Church can be seen on the left, where once stood the Olvera Adobe. Several large gas storage tanks are in the background. |

|

|

| (1892)* - Identical view of the Plaza taken from the exact same spot as the previous photo but in 1892 (44 years earlier) with the Olvera Adobe on the left. |

Before and After

|

|

|

| (1892)* - View showing the LA Plaza with the Olvera Adobe at left background and Olvera Street adjacent to it. | (1936)^*# - View of the LA Plaza showing the Plaza Methodist Church at upper-left where the Olvera Adobe once stood. |

Historical Notes The Olvera Adobe was torn down in 1917 and, nine years later, architects Train and Williams completed the Churrigeresque-style Plaza Methodist Church. |

Old Plaza Church

|

|

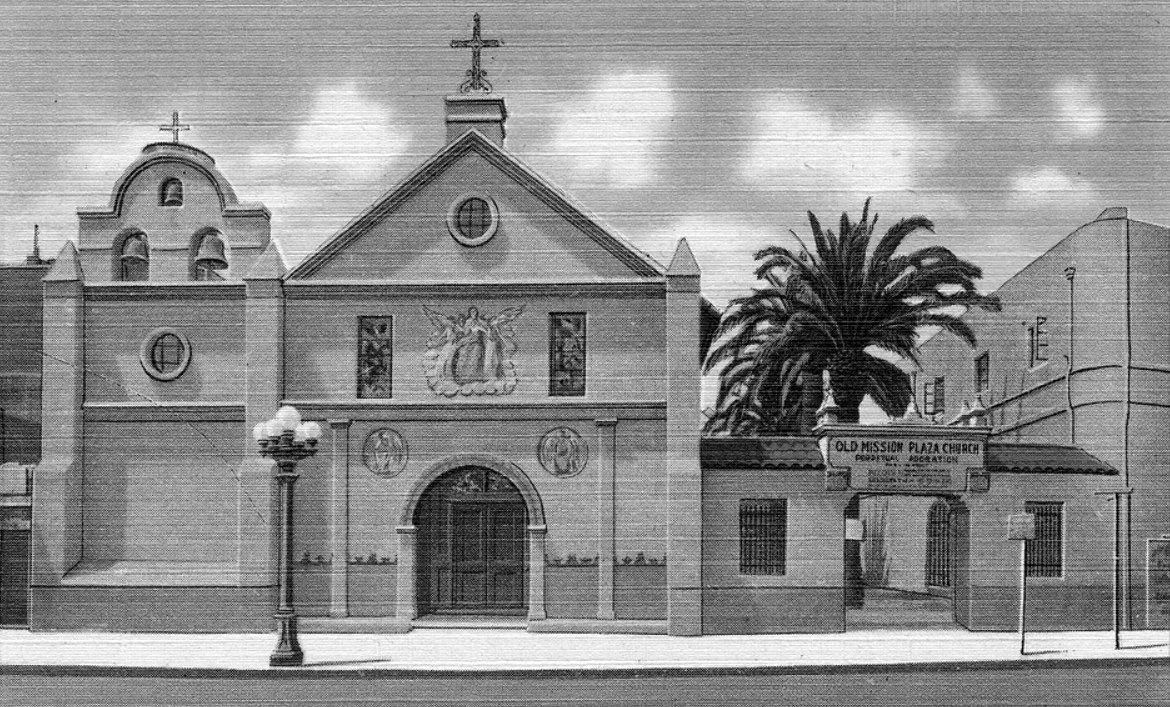

| (ca. 1930)##* – Postcard view of Our Lady, Queen of Angels, Old Mission Plaza Church. |

|

|

| (ca. 1937)** - A man is crossing Main Street directly outside of La Plaza Church. Signage on a water tower (upper left) promotes the nearby "Brunswig Drug Co." Photo by Herman J. Schultheis |

|

|

| (1937)** - According to the sign above the awning "giant malts" and "coloso ice cream cones" can be found at this Mexican ice cream store. Located at 523 North Main Street, El Popo is seen next door to the bells and crosses of the Plaza Church. |

Felipe de Neve Statue

|

|

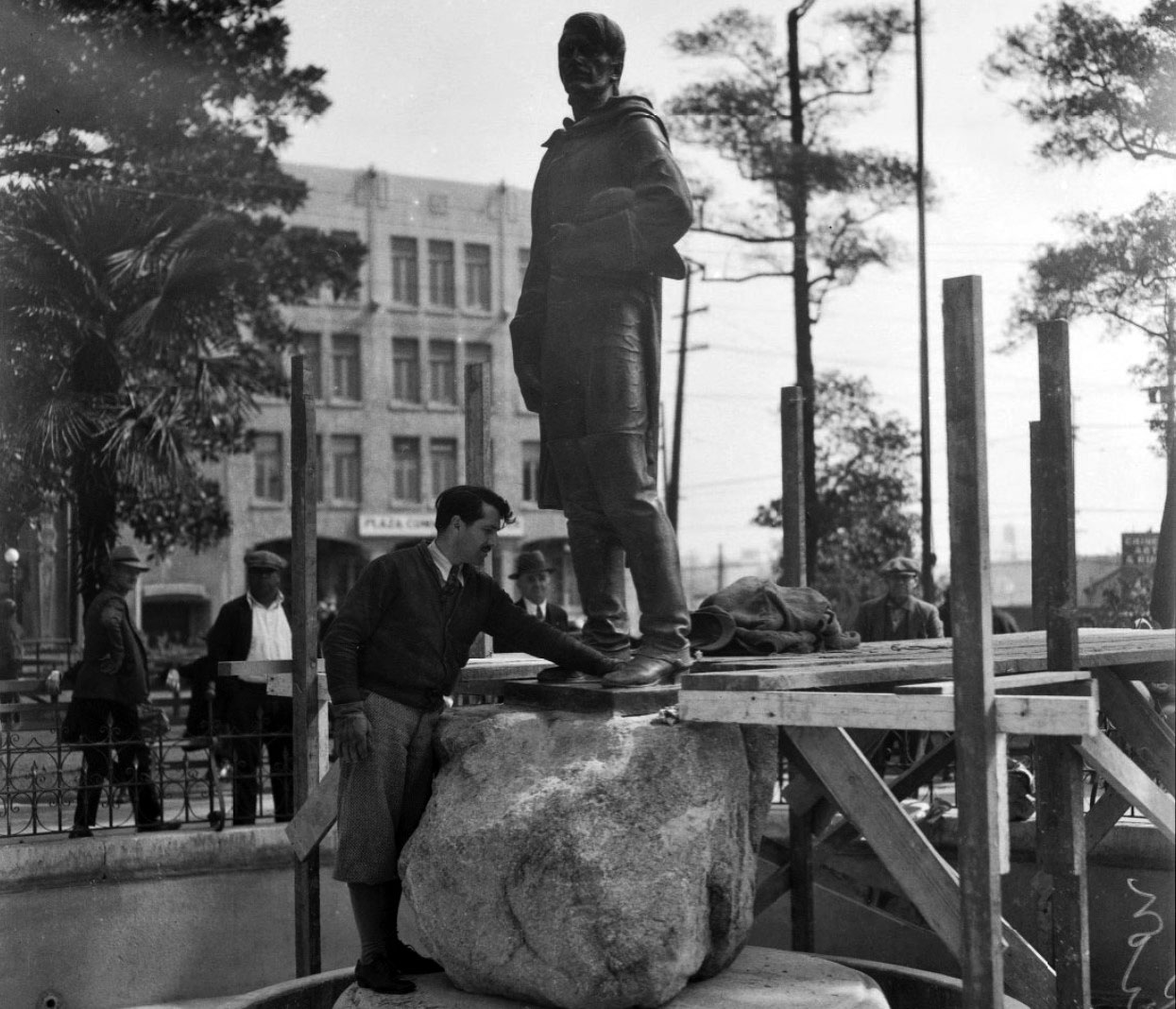

| (1932)* - Sculptor Henry Lion completing the installation of his statue of Felipe de Neve in La Plaza Park. LA Times / UCLA Image Archives |

Historical Notes Felipe de Neve (1724–1784) was the fourth governor of Las Californias, a province of New Spain, from 1775 to 1782. Neve is considered a founder of Los Angeles and helped to settle towns of Santa Barbara and San José whose surrounding communities became California cities. In 1781, Neve issued the first rules regarding governance of secular pueblos like Los Angeles, the "Regulations for the Government of the Province of the Californias" (Reglamento para el gobierno de la provincia de Californias).^ Sculptor Henry Lion was born in Fresno, California. He studied at the Otis Art Institute and with Stanton Macdonald-Wright. Most of his works were executed in bronze. Lion wrote the book SCULPTURE FOR BEGINNERS, and worked on the WPA art project. |

|

|

| (1932)* – Close-up view of the statue of Don Felipe de Neve shortly after being placed in the pool at center of the Plaza. LA Times / UCLA Digital Archives |

Historical Notes In 1932, the 7 foot high statue of De Neve was set in the 1873 pool at the center of the Plaza facing the Plaza Church. The statue was donated by the Daughters of the Golden West. |

|

|

| (ca. 1937)** - Felipe de Neve statue at the center of the Los Angeles Plaza Park |

Historical Notes The inscription on the statue reads: "Felipe de Neve (1728-84). Governor of California 1775-82. In 1781, on orders from King Carlos III of Spain, Felipe de Neve selected a site near the River Porciuncula and laid out the town of El Pueblo de La Reina de Los Angeles, one of two pueblos he founded in Alta California." |

* * * * * |

|

|

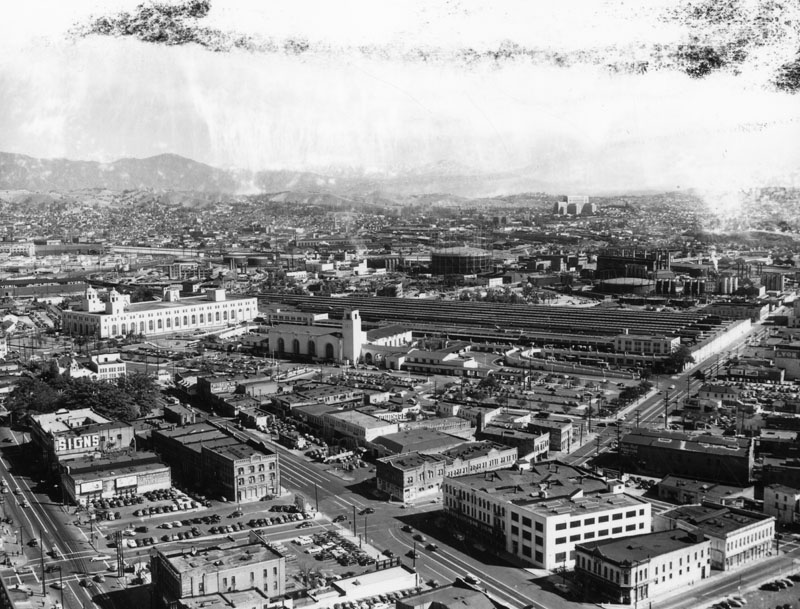

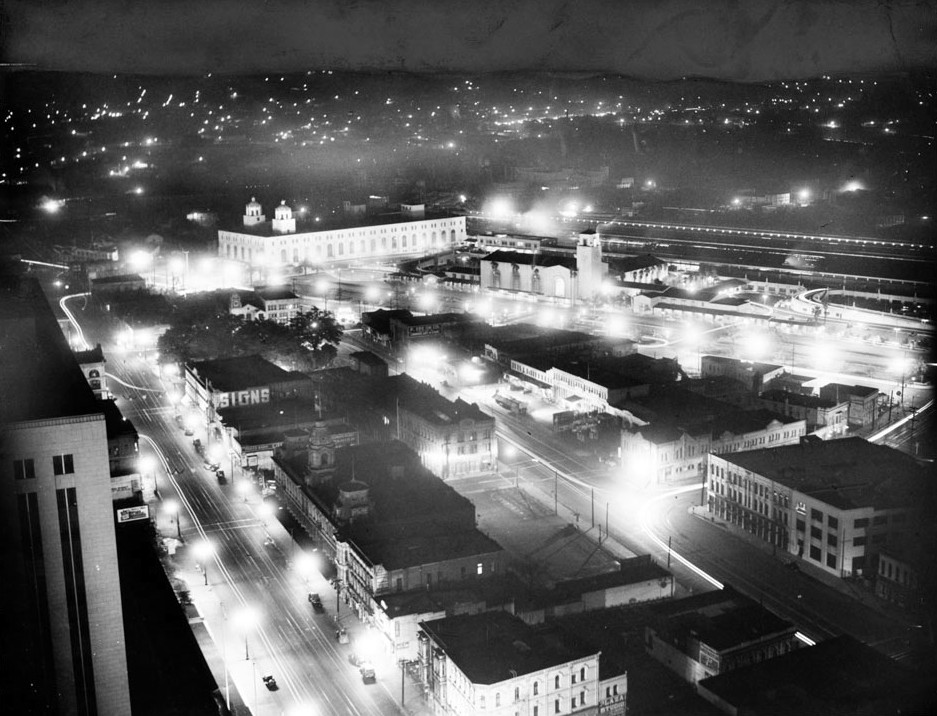

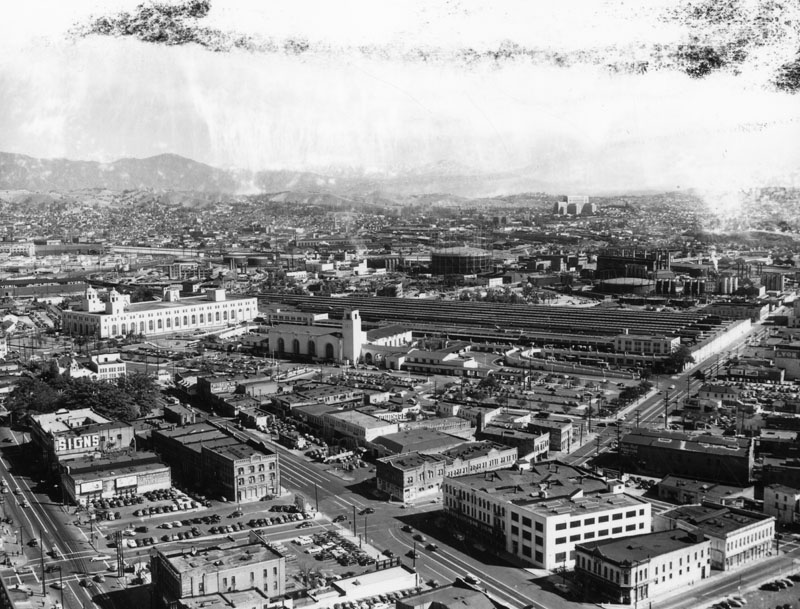

| (ca. 1930)*** – View of the proposed site for Union Station construction. This is one of the oldest areas in the City, with the Los Angeles Plaza at center and Chinatown at lower right. Main Street is seen at lower center running towards the background. Baker Block is at lower center-right. |

Historical Notes In 1926, a measure was placed on the ballot giving Los Angeles voters the choice between the construction of a vast network of elevated railways or the construction of a much smaller Union Station to consolidate different railroad terminals. The election would take on racial connotations and become a defining moment in the development of Los Angeles. The proposed Union Station was located in the heart of what was Los Angeles' original Chinatown. Reflecting the prejudice of the era, the conservative Los Angeles Times, a lead opponent of elevated railways, argued in editorials that Union Station would not be built in the “midst of Chinatown” but rather would “forever do away with Chinatown and its environs.” Voters approved demolishing much of Chinatown to build Union Station by a narrow 51 to 48 percent.^* |

|

|

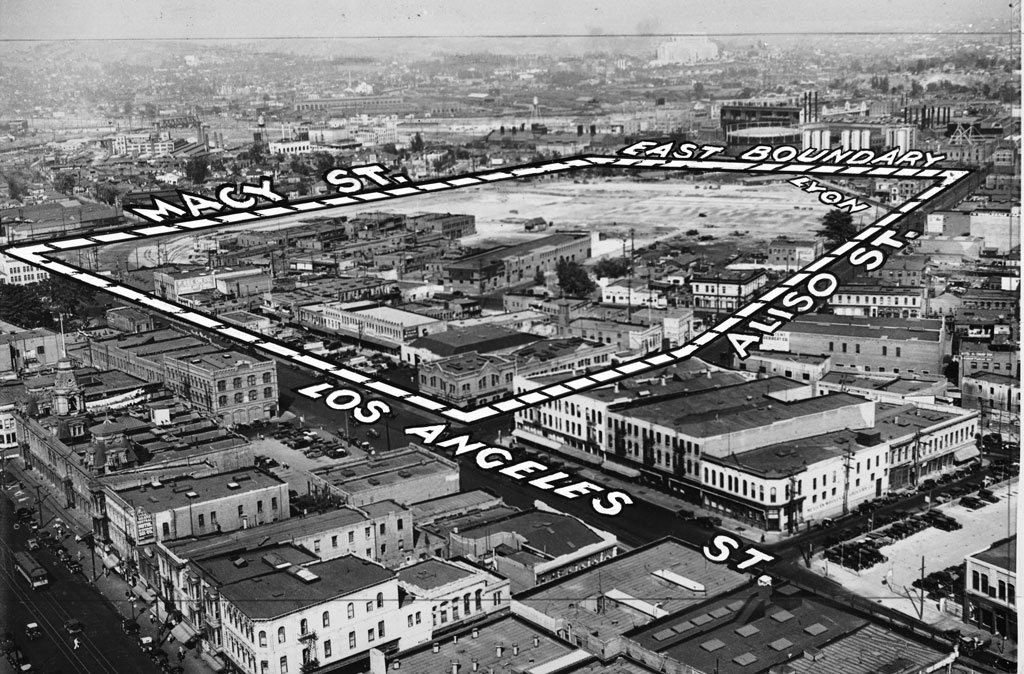

| (1933)*** - Panoramic view showing the Los Angeles Plaza (arrow) and surrounding area including most of Chinatown. The photo has been annotated to delineate the boundaries of the proposed new Union Station. |

Historical Notes The above photo comes from the September 18, 1933 issue of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. The article reads: "Chinatown faces extinction in Los Angeles with erection of the new Union Station on the Plaza site. The area enclosed by broken line will be occupied with tracks and the station. It includes most of Chinatown. Upper left hand line shows where trains enter station area from Southern Pacific bridge over Los Angeles River." *** |

|

|

| (1934)*** - Caption reads: “Site of new Union Terminal (enclosed by lines), where dirt to be removed from Fort Moore Hill will be used for filling in. This great depot will serve all steam railroads entering Los Angeles. Chinatown is seen in foreground of station site." The Los Angeles Plaza can be seen at left-center. The old Baker Block is still standing (lower-left). |

Historical Notes The ornate three-story Baker Block was completed in 1878 by Colonel Robert S. Baker. For a number of years, the building housed offices, shops, and apartments. Goodwill Industries of Southern California purchased it in 1919. Despite plans to relocate the structure for another purpose, the city purchased the Baker Block from Goodwill in 1941 and demolished the building a year later. U.S. Route 101 now runs beneath where these buildings once stood.^ Click HERE to see more in Early LA Buildings (1800s). |

.jpg) |

|

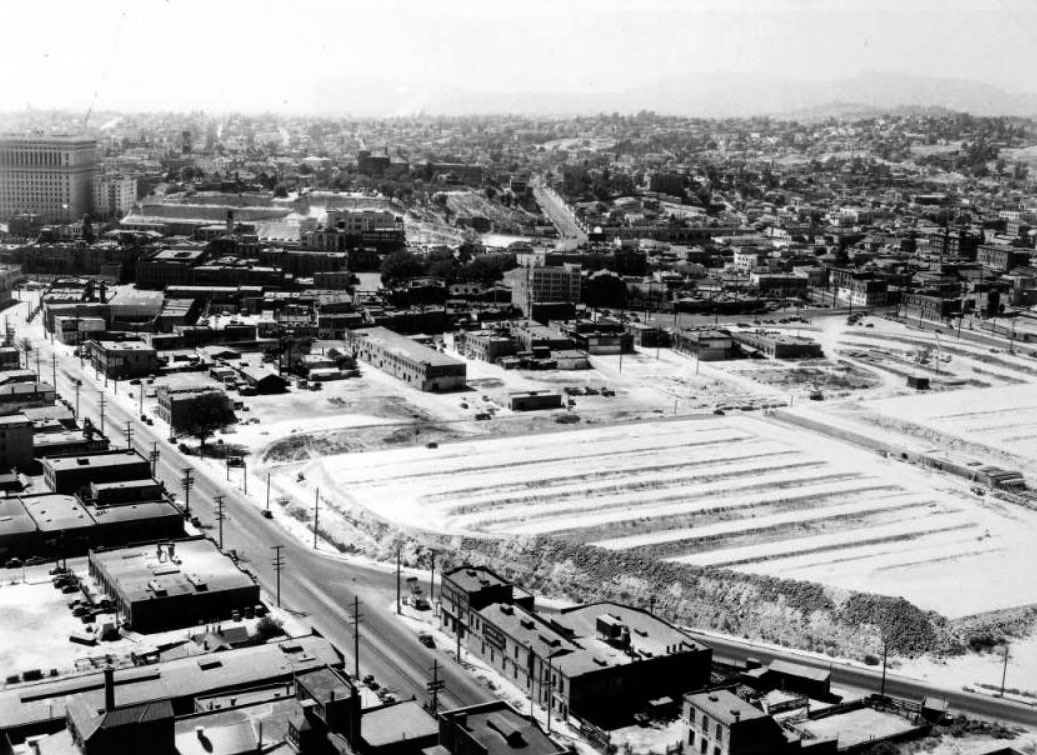

| (1935)*** - View looking west across Lyon Street near its intersection with Aliso Street. The Union Station construction site is seen at center. Ridges in the area are fills, where tracks will be laid. In center, under construction, is the pedestrian tunnel to the tracks. The LA Plaza is at upper-left. Photo Date: August 19, 1935 |

|

|

| (1935)*** - Panoramic view of the construction of Union Station looking northwest from the top of the Los Angeles Gas and Electric tank, August 27, 1935. The site of the terminal is at right and is a trapezoidal area full of graded dirt. The LA Plaza can be seen in the upper-center left. The Hall of Justice Building stands in the upper left. |

Historical Notes By the early 1950s, the section of the 101 Freeway (Hollywood Freeway) that runs through downtown would go right through where Aliso Street is shown above, running diagonally away from bottom center of photo. |

|

|

| (1938)*** - View looking north toward Union Station, still under construction. The main road going along the left side of the photo is Alameda Street. Aliso Street is at the southern end of the station near where the Hollywood Freeway is located today. The LA Plaza is out of view at left-center. |

Historical Notes When Union Station was opened in May 1939, it consolidated remaining service from its predecessors La Grande Station and Central Station. It was built on a grand scale and became known as "Last of the Great Railway Stations" built in the United States.^* |

|

|

| (1939)*** - Crowds watch early model train while celebrating completion of the new Union Station located at 800 N. Alameda Street. |

Historical Notes Examiner clipping attached to verso, dated May 4, 1939: "Stirring awake memories that had slumbered for more than a century, railroad officials yesterday staged a colorful pageant of transportation that thrilled thousands of Angelenos for two hours. Gayly costumed ladies of the Gay Nineties -- and the years before -- rode stage coaches and horse cars and stuttering, slow-moving trains of another era. Derby-hatted, mustachioed gentlemen in tight coats pumped high-wheeled bicycles -- 'bone-crushers' they were known as in those days -- all to celebrate formal opening of the new Union Station, pictured in background as oldest Union Pacific train approaches the city's newest in beautiful architecture." *** |

|

|

| (1940)** - Exterior view of Los Angeles Union Station, showing several palm trees, arched windows, and the large tower and clock. |

Historical Notes Union Station was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. It also is listed as Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 101. Click HERE to see more on the Los Angeles Union Station. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)*** - View of downtown looking southwest from where Union Station sits today. The new Federal Courthouse Building is under construction as seen between City Hall and the Hall of Justice. Alameda Street is in the foreground. The old Baker Block with its distinctive three towers still stands at the center of photo. |

Historical Notes The area in the extreme foreground is now Union Station. The street in front is Alameda Street, and those buildings ahead of Alameda were knocked down and are now landscaping and on ramps to the 101 Hollywood/Santa Ana Freeway. Old Chinatown started being demolished around 1933, and Union Station opened in 1939.^*# To the right-center of the photo is the Pico House in front of the LA Plaza which is out of view to the right. The old 1877-built Baker Block with it's distinctive three towers can be seen in the center of the photo just below the Federal Courthouse Building. The Baker Block would be demoished in 1942 to make room for the 101 Freeway. Click HERE to see more on the Baker Block. |

|

|

| (1939)^*# - View of the Plaza with the LA downtown skyline in the background. From left to right stand City Hall, the Federal Courthouse still under construction (completed in 1940), the Hall of Records, and the Hall of Justice. The old Brunswig Building can also be seen on the other side of the LA Plaza across from the Pico House. |

|

|

| (1939)* - Exterior front view of the two-story Vincent Lugo Adobe house, located on Los Angeles Street and facing the Plaza. It is now flanked by brick buildings, with cars parked on the street in front. |

* * * * * |

Marchessault and Los Angeles Street

|

|

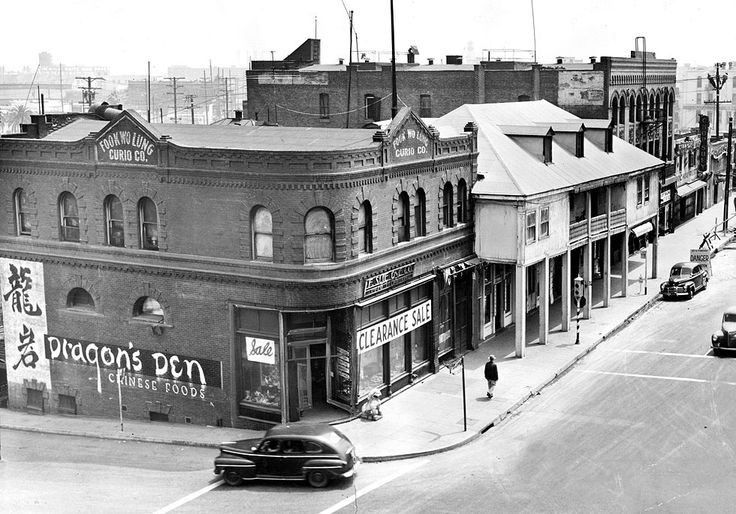

| (1930s) – Looking at the SE corner of Los Angeles and Marchessault streets showing Ying's Art Shop located in Fook Wo Lung Curio Company building. To its right is the old Vincent Lugo Adobe house. |

Historical Notes Marchessault Street was located along the north side of the historic Los Angeles Plaza. It was named after Damien Marchessault, a French-born two-time mayor of the city who later died by suicide. |

|

|

| (ca. 1939)** - View of Chinatown, looking south on Los Angeles and Marchessault streets. The Dragon's Den, a Chinese food restaurant, is in the Fook Wo Lung Curio Company building at the corner of the block. |

|

|

| (1949)*^# - View of the southeast corner of Marchessault and Los Angeles St. The old two-story Vincent Lugo Adobe house can be seen with its hipped roof and dormer window. It sits directly across the street from the LA Plaza. The brick building on the corner is the Fook Wo Lung Curio Company building. The painted sign on its side reads: Dragon's Den Chinese Food. |

Historical Notes In 1935, Eddy See opened the Dragon's Den Restaurant in the basement of the F. Suie One Company. On the exposed brick of the basement walls, Benji Okubo, Tyrus Wong and Marian Blanchard painted murals of the Eight Immortals and a dancing dragon. An arty crowd, including Walt Disney and the Marx Brothers, came to see the murals and sample the "authentic fare." In an era when Chinese restaurants were known as chop-suey joints, Dragon's Den served egg foo young, fried shrimp and almond duck. Non-Chinese diners during the Great Depression considered these "exotic" dishes. |

|

|

| (1950)* - View of Fook Wo Lung Curio Company building, containing the Dragon's Den Chinese Foods, SE corner of Alameda and Marchessault streets. |

|

|

| (ca. 1939)* - View looking up Marchessault Street (with Alameda Street crossing at bottom and Los Angeles Street crossing at mid distance) shows the LA Plaza. The old Water Department Building, now occupied by the F. See On Company, stands on the northwest corner of Marchessault and Alameda. |

Historical Notes In 1939, the first home of the Department of Water and Power was sold to the City to make way for the Civic Center development planned in connection with the new Union Passenger Depot. Located at the corner of Marchessault and Alameda Streets, directly across from the almost completed railroad station, the property was the main office of the municipal water works when the City bought out the private water companies operating here until 1902. |

|

|

| (1939)* - View looking toward Union Station from the SE corner of Marchessault and Los Angeles streets. Photo caption reads: "Another Landmark Gives Way to Progress -- Photo shows wrecking yesterday of first home of the Department of Water and Power, recently purchased by the City, to make a wide approach by way of Marchessault Street to the new Union Station. With work being rushed, thousands of persons will occupy the site of this landmark on May 3, when the celebration's parade passes on Alameda Street. The old building was the main office of the municipal water works when the City bought out the private water companies operation here until 1902." |

Historical Notes Click HERE to see more in Water Department's Original Office Building. |

|

|

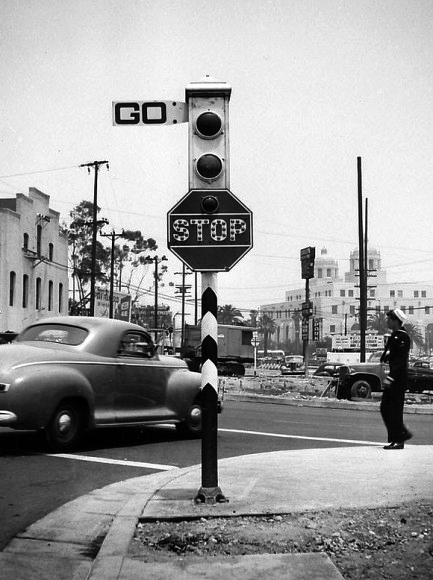

| (ca. 1942)* – View looking toward the Terminal Annex Building showing an Acme Semaphore Traffic Signal standing on the southeast corner of Marchessault and Los Angeles streets. To the left is the eastern face of the Plaza Substation building. Seen on the right is a sailor in uniform about to cross Los Angeles Street, heading toward the Plaza. Behind him, on the other side of the street, is where the old Water Department Building once stood. |

|

|

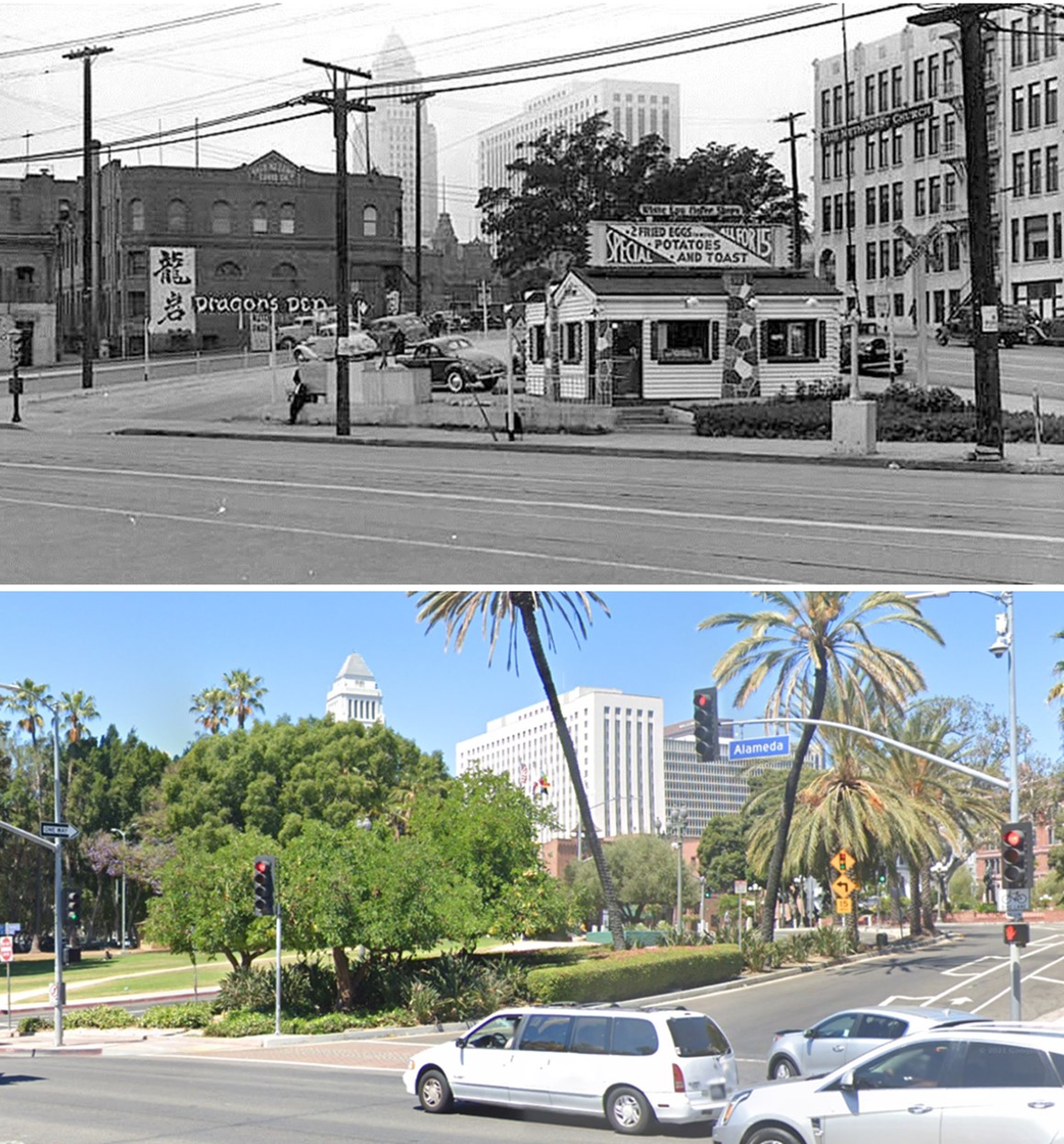

| (1943)* – Looking SW towards the LA Plaza and the Civic Center from N. Alameda, north of where it crosses Marchessault Street(left). Union Station is behind the camera. Seen here are Tyrus Wong's Dragon's Den Chinese Foods Restaurant (part of Old Chinatown), a glimpse of the Baker Block on Main Street, City Hall, the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse, the headquarters of the Southern California-Arizona Conference of the Methodist Church (in what later became the Biscailuz Building), and a White Log Coffee Shop. |

Historical Notes Today, Los Angeles Street curves sharply to the right into Alameda Street where Marchessault Street once existed. |

|

|

| (2021)* - Looking SW toward the LA Plaza and the Civic Center from Alameda Street and Los Angeles Street (originally where Marchessault Street intersected with Alameda Street. Union Station is behind the camera. |

Historical Notes Los Angeles Street now curves sharply to the right into Alameda Street where Marchessault Street once existed. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1943 vs 2021)* - Looking SW toward the LA Plaza and the Civic Center from Alameda Street and Los Angeles Street (originally where Marchessault Street intersected with Alameda Street. Union Station is behind the camera. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1939 vs 2022)* - Looking SW toward the LA Plaza from Alameda Street and Los Angeles Street (originally where Marchessault Street intersected with Alameda Street. Union Station is behind the camera. |

Then and Now

|

|

| (1939 vs 2022)* - Looking SW toward the LA Plaza from Alameda Street and Los Angeles Street (originally where Marchessault Street intersected with Alameda Street. Union Station is behind the camera. The LA Plaza and Plaza Substation are highlighted to get a better perspective. |

|

|

| (ca. 1940)* - Aerial view of the Civic Center, Union Station and the LA Plaza. The Plaza is in the upper center-left of photo. The flattened lot of the where the old Water Department building once stood can be seen just to the northeast of the Plaza. |

* * * * * |

Marchessault and Alameda Street |

At Alameda and Marchessault Streets, Los Angeles once had a very different face. This intersection sat within the city’s original Chinatown near the Plaza, where Chinese immigrants built businesses, institutions, and daily life within a district shaped by segregation and exclusion.

|

Life in Old Chinatown |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1900)* – View looking east on Marchessault Street at Alameda Street in Los Angeles’ original Chinatown. |