Los Angeles City Hall - Building a Civic Landmark

Completed in 1928, Los Angeles City Hall was built to announce that the city had come of age. Rising above the Civic Center with a bold central tower, it symbolized confidence, growth, and belief in the future. At a time when Los Angeles was still shaping its identity, City Hall became both a working government building and a visual statement of civic pride. Its construction, dedication, and long presence on the skyline reflect how Los Angeles saw itself and how it wanted the world to see it. |

|

|

| (1928)* - View of Los Angeles City Hall decorated with banners for its opening ceremony. Bleachers line Spring Street as crowds gather for parades and public celebrations. |

| Historical Notes

This image captures Los Angeles at a moment of shared civic pride. Downtown streets were transformed into public gathering spaces as residents came out to witness the dedication of the new City Hall. Contemporary accounts describe large crowds attending multiple days of ceremonies, parades, and speeches. The celebration reflected a widespread belief that Los Angeles had reached a turning point, ready to present itself as a major American city with a monumental seat of government. |

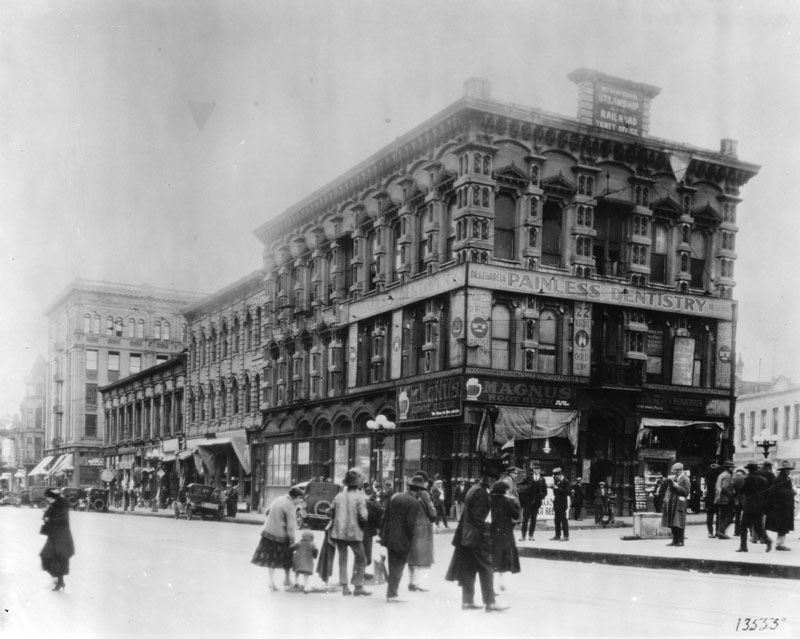

The Site Before City Hall

|

|

| (ca. 1926)* - View showing the Temple Block at the intersection of Spring, Main, and Temple streets. This triangular block would soon be cleared to make way for the new City Hall. Ground was broken on March 4, 1926. |

| Historical Notes

For decades, Temple Block was the commercial and civic heart of Los Angeles. The wedge-shaped block at Main, Spring, and Temple streets held offices, shops, and early city institutions. One of the city’s first stores was established here in the 1850s by Jonathan Temple, for whom Temple Street was named. By the 1920s, the aging buildings no longer matched the city’s ambitions. Clearing Temple Block marked a deliberate decision to replace the old commercial core with a formal civic center built to express permanence and authority. |

|

|

|

|

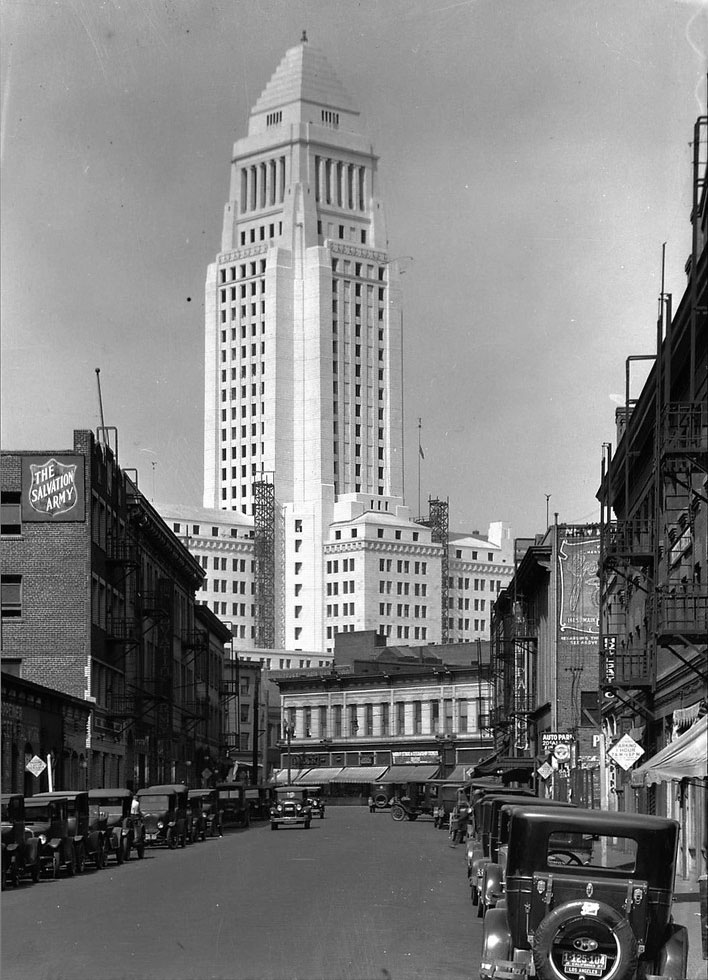

| (1911 - 1930)* - Before and after view looking toward the southeast corner of Temple and Broadway, showing the area before City Hall and after its completion in 1928. |

| Historical Notes

This comparison shows one of the most dramatic transformations in downtown Los Angeles. Low rise commercial buildings and narrow streets were replaced by a towering civic monument designed to dominate the skyline. The change was more than architectural. It reflected a shift in how the city defined itself, placing public government at the center of downtown and signaling a move toward a planned, monumental civic identity. |

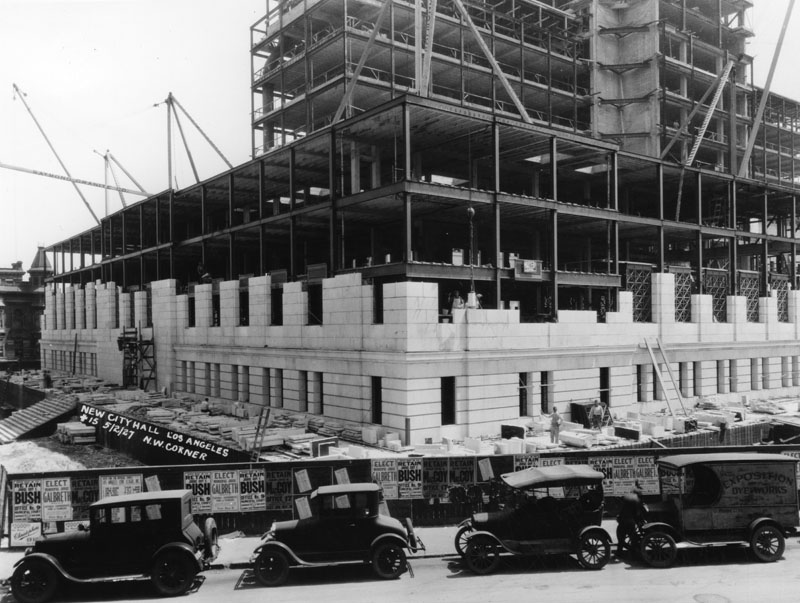

Designing a City Symbol

|

|

| (1927)* - Steel framing rises rapidly as the new City Hall takes shape, dwarfing the remaining structures of Temple Block. |

| Historical Notes

After voters approved a bond issue in 1923, the city commissioned architects John Parkinson, Albert C. Martin, and John C. Austin in August 1925. Parkinson developed the overall architectural concept, Martin handled the structural engineering, and Austin oversaw working drawings and project administration. Once construction began, the steel frame climbed quickly, making City Hall a highly visible symbol of Los Angeles’s civic ambitions even before it was finished. |

|

|

| (1927)* - View showing early automobiles and a streetcar passing the construction site as City Hall’s steel framing nears completion. |

| Historical Notes

This scene captures Los Angeles in transition. Streetcars, early automobiles, and pedestrians move through the same streets as the city’s new civic landmark rises behind them. The 28 story City Hall replaced the Romanesque Revival City Hall built in 1888 on Broadway between 2nd and 3rd streets. That earlier building had replaced an even older one story adobe City Hall, formerly the Rocha House, located at Spring and Court streets. Each replacement reflected the city’s steady growth in size, complexity, and civic ambition. |

|

|

| (1927)* - Los Angeles City Hall beginning to take form at 200 North Spring Street. |

| Historical Notes

By this stage, the building’s distinctive tower was clearly defined. At 454 feet tall, City Hall was designed to become the tallest building in Los Angeles, a distinction it would hold for more than 30 years. Its form and scale were carefully chosen to project authority, permanence, and civic pride, combining classical inspiration with modern construction methods. For many years, city rules limited the height of most buildings in Los Angeles to about 150 feet, allowing taller structures only if they were decorative towers. Because of this restriction, City Hall’s central tower stood far above all other buildings downtown. These height limits remained in place until the late 1950s, which is why City Hall remained the city’s tallest structure for more than three decades. |

Building the Tower

|

|

| (1927)* - Exterior stone begins to be added to Los Angeles City Hall as construction advances upward. |

| Historical Notes

As the steel frame was completed, crews began enclosing the building with stone and masonry. This phase marked a visible shift from raw structure to finished landmark. The exterior materials gave City Hall its solid, monumental appearance, reinforcing the idea that the building was meant to endure and to symbolize stability in a rapidly growing city. At 454 feet tall, City Hall was designed to rise far above its surroundings. Upon completion, it became the tallest building in Los Angeles, a distinction it would hold for more than 30 years. |

|

|

| (1927)* - View showing the northwest corner of Los Angeles City Hall during construction, May 2, 1927. |

| Historical Notes

This image shows the scale of the building as the tower continued to rise above the Civic Center. One of the most symbolic aspects of its construction was the concrete used in the tower. It was made with sand collected from each of California’s 58 counties and water from its 21 historic missions. The gesture was intentional, linking City Hall to the entire state and its history, not just to the city it served. |

|

|

| (1927)* - View of the new Los Angeles City Hall more than halfway completed. |

| Historical Notes

By this stage, City Hall’s distinctive tower was clearly defined and already dominated the skyline. Its form was inspired by the ancient Mausoleum of Mausolus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and reflects the influence of the nearby Los Angeles Central Library, completed shortly before construction began. The design blended classical references with modern construction methods, reinforcing the idea that Los Angeles was both forward looking and rooted in tradition. |

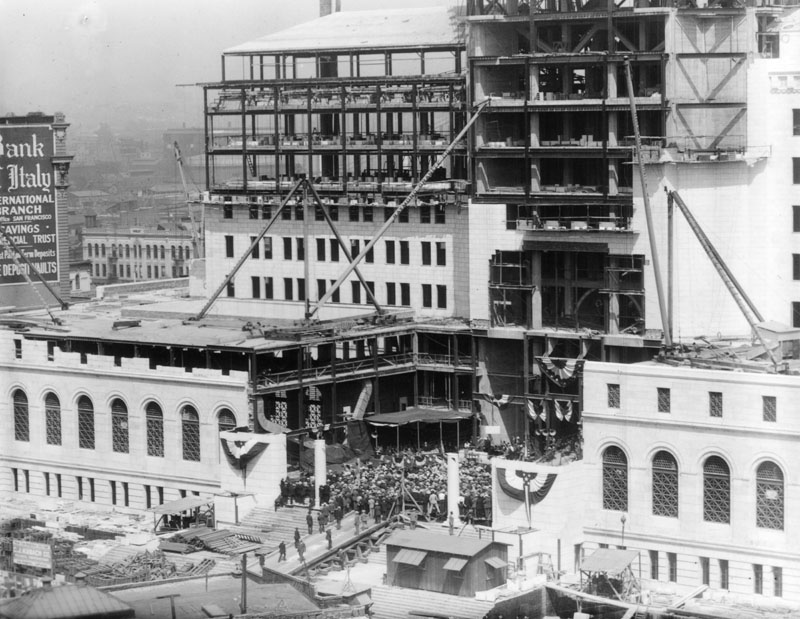

Marking Progress and Ceremony

|

|

| (1927)* - Ceremony marking the halfway completion of the new Los Angeles City Hall. |

| Historical Notes

Public ceremonies were used throughout construction to mark progress and build public support. The halfway completion event emphasized that City Hall was not just a building project, but a shared civic achievement. These ceremonies helped keep the public engaged and reinforced the idea that the structure belonged to the people of Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1927)* - Cornerstone for the new Los Angeles City Hall being lowered into position. |

| Historical Notes

The laying of the cornerstone was one of the most symbolic moments in the construction process. The ceremony drew city leaders, state officials, and large crowds. A sealed copper box was placed inside the cornerstone containing historical documents, photographs, and artifacts meant to represent Los Angeles at that moment in time. The contents reflected a desire to preserve the city’s story for future generations. The event was treated as major news, complete with speeches, a formal procession, and live radio coverage, underscoring the importance City Hall held in the civic life of the city. |

|

|

| (2015)* - The cornerstone for Los Angeles City Hall, located to the left of the original Spring Street entrance, now closed. Photo by Scott Harrison. |

| Historical Notes

Today, the cornerstone remains in place as a physical reminder of City Hall’s construction and the values associated with its founding. While the original entrance nearby is no longer in use, the cornerstone continues to connect the present building with the moment when Los Angeles formally laid claim to its role as a major American city. |

Approaching Completion

|

|

| (1928)* – Los Angeles City Hall under construction as seen from the upper terminus of Angels Flight at 3rd and Olive streets |

| Historical Notes

Seen from Bunker Hill, City Hall rises clearly above the surrounding city as construction nears completion. The view from Angels Flight emphasizes how dominant the new building had become on the skyline. From this vantage point, the tower appears as a focal point for downtown Los Angeles, visually tying the older hilltop neighborhoods to the emerging Civic Center below. |

|

|

| (1928)* - City Hall near the final stage of completion, prior to landscaping. |

| Historical Notes

By early 1928, the main structure of City Hall was largely complete, with only finishing work and landscaping remaining. The building’s clean lines and tall central tower set it apart from every other structure in the city. At this moment, City Hall stood not only as a functional government building, but as a carefully staged symbol of order, permanence, and civic authority. For decades, Los Angeles had avoided vertical development through strict height limits. As a result, City Hall’s tower remained unmatched, giving it a commanding presence that defined the city’s skyline well into the mid twentieth century. |

|

|

| (1928)* - View showing the nearly completed City Hall building as seen from Weller Street, now Onizuka Street, in Little Tokyo. Metal scaffolding remains near the base of the tower. |

| Historical Notes

This view from the east shows City Hall towering above nearby commercial buildings and residential neighborhoods. The remaining scaffolding near the base signals that work was still underway, but the overall form of the building was complete. Seen from Little Tokyo, City Hall appeared both distant and monumental, reinforcing its role as the central seat of government for a rapidly expanding city. |

|

|

| (1928)* - View showing the nearly completed City Hall building as seen from Weller Street, now Onizuka Street, in Little Tokyo. Image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

| Historical Notes

When City Hall opened its doors later in 1928, it was already embraced by the public as a powerful symbol of Los Angeles’s transformation. Before most residents ever set foot inside, the building had become a shared point of pride. Hundreds of thousands of people would soon line downtown streets for dedication events, drawn by the sense that the city had entered a new stage in its history. |

Preparing for the Grand Opening

|

|

| (1928)* - View of the new Los Angeles City Hall as final preparations are made for its opening. Sky writing above the building reads “prosperity.” |

| Historical Notes

As construction wrapped up, attention shifted from building the structure to presenting it to the public. Decorations were added, streets were prepared for large crowds, and City Hall was framed as a symbol of optimism and economic confidence. The skywriting message reflected the mood of the late 1920s, when Los Angeles leaders promoted the city as forward looking, stable, and open for growth. The building’s design blended classical, Mediterranean, and modern elements, with granite at the lower levels and terra cotta above. This combination reinforced the idea that City Hall was both dignified and modern, rooted in tradition while embracing the future. |

Opening Ceremony, April 1928

|

|

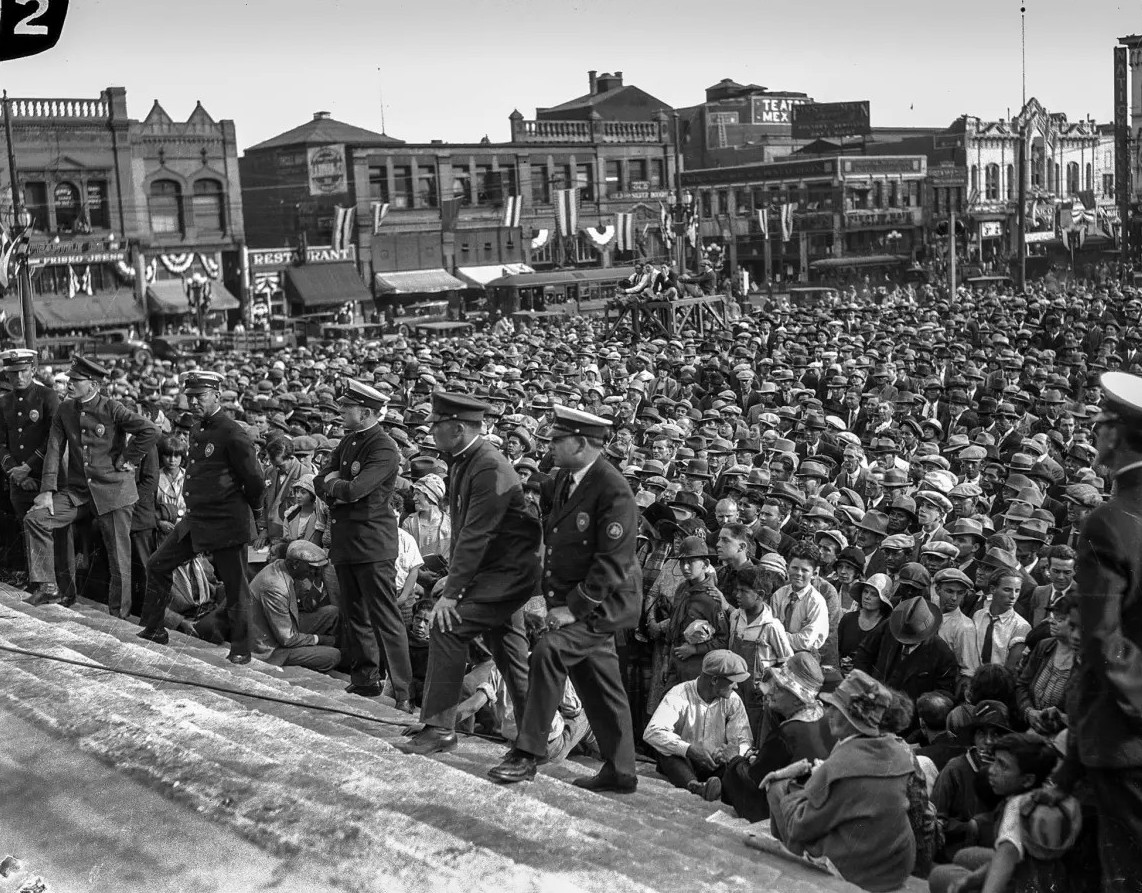

| (1928)* - Daytime dedication ceremony of the newly completed Los Angeles City Hall, photographed from the side facing 1st Street. |

Historical Notes The official dedication of Los Angeles City Hall took place over several days in April 1928 and drew large crowds downtown. Streets surrounding the building were closed to traffic and lined with spectators as city leaders, visiting officials, and performers took part in the ceremonies. The daytime events emphasized City Hall’s role as a working government building and a public gathering place at the heart of the city. Speeches and presentations focused on Los Angeles’s growth and future promise, reinforcing the idea that the city had reached a new level of national importance. |

|

|

| (1928)* - Crowd at Los Angeles City Hall dedication ceremonies. The program was held on the South Terrace of City Hall. Buildings along Spring Street are visible in the background. News cameras appear at left. (Los Angeles Times Archive / UCLA) |

| Historical Notes

Large crowds gathered throughout the Civic Center during the dedication events. Temporary platforms and staging areas were set up to accommodate speakers, performers, and the press. Newsreel cameras and photographers documented the ceremonies, ensuring wide coverage beyond those in attendance. The presence of media reflects how closely the opening of City Hall was followed both locally and nationally. |

|

|

| (1928)* - Crowd at Los Angeles City Hall dedication ceremonies with Main Street visible in the background. (Los Angeles Times Archive / UCLA) |

| Historical Notes

Views from multiple angles show how the dedication extended beyond the building itself and into the surrounding streets. Main Street, one of downtown’s primary corridors, became part of the celebration as spectators filled sidewalks and open areas. The scale of attendance highlighted public interest and pride in the city’s new civic landmark. |

|

|

| (1928)* - Mayor George E. Cryer speaks during the dedication ceremonies for the new Los Angeles City Hall. (Los Angeles Times Archive / UCLA) |

| Historical Notes

Mayor Cryer’s remarks emphasized City Hall as a symbol of stability, progress, and confidence in the city’s future. Civic leaders presented the building not only as a seat of government but as a statement of Los Angeles’s ambitions. The speeches formed the formal centerpiece of the dedication program. |

|

|

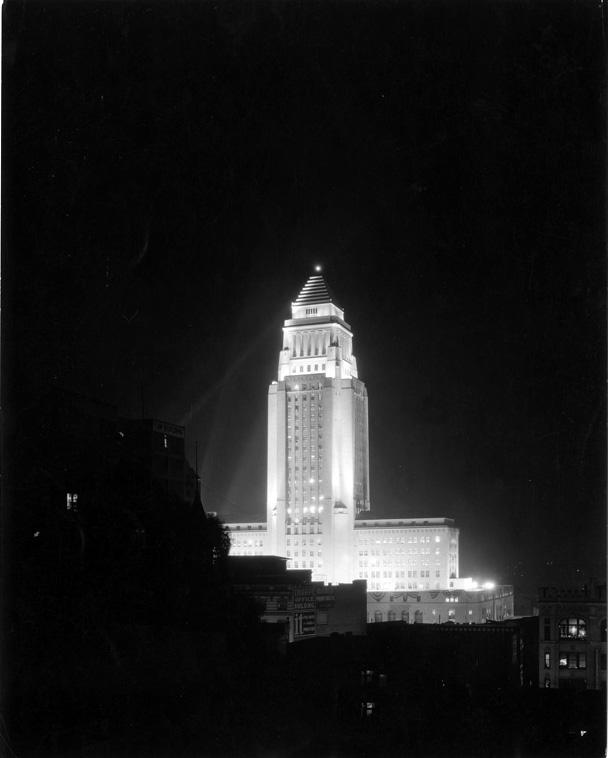

| (1928)* - Nighttime view of Los Angeles City Hall during opening ceremonies, illuminated and decorated for the occasion. |

| Historical Notes

The opening ceremonies extended into the evening, transforming City Hall into a dramatic nighttime landmark. Powerful spotlights illuminated the tower, making it visible across much of the city and introducing many residents to the idea of a civic building designed to be seen after dark. These nighttime views marked City Hall’s first appearance as a visual centerpiece of downtown Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1928)* - Nighttime view of Los Angeles City Hall as seen from Bunker Hill, with banners displayed on the building. |

| Historical Notes

Seen from Bunker Hill, City Hall rises prominently above the surrounding city, its illuminated tower glowing against the night sky. This vantage point highlights how dramatically the building altered downtown’s visual balance. For residents accustomed to a low skyline, the tower served as a clear sign that Los Angeles had entered a new phase of growth and ambition. |

|

|

| (1928)* – View looking down from Bunker Hill toward City Hall during opening ceremonies. The Los Angeles Times Building clock tower is visible at right. |

| Historical Notes

This view places City Hall within the broader downtown landscape during its debut. The presence of the Los Angeles Times Building reflects the close relationship between civic life and the press during this period. From Bunker Hill, the illuminated tower appears as the visual anchor of downtown Los Angeles, reinforcing City Hall’s role as the city’s civic center. |

City Hall at Night and the Lindbergh Beacon

|

|

| (1936)* - Los Angeles City Hall illuminated at night during the Celebration of Electric Power, marking the completion of the Hoover Dam, then known as Boulder Dam. The Lindbergh Beacon glows at the top of the tower. |

| Historical Notes

In 1936, City Hall again became the focus of a major public celebration, this time marking the arrival of power from Hoover Dam to Los Angeles. The building was dramatically illuminated as part of the Celebration of Electric Power, highlighting both technological achievement and the city’s growing infrastructure. The Lindbergh Beacon, mounted atop the tower, played a central visual role in the event. |

|

|

| (1936)* - Nighttime view of Los Angeles City Hall with multiple spotlights projecting from the tower during the Celebration of Electric Power. |

| Historical Notes

By night, City Hall functioned as a beacon both literally and symbolically. The powerful spotlights reinforced its dominance on the skyline and reflected Los Angeles’s desire to present itself as modern, confident, and forward looking. Events like this demonstrated how City Hall had been designed to command attention day and night. |

| (1930s)* – Postcard view showing Los Angeles City Hall and the Civic Center with the Lindbergh Beacon shining high into the sky. |

| Historical Notes

Postcards from the 1930s frequently featured the Lindbergh Beacon as one of downtown Los Angeles’s most distinctive nighttime elements. Rising above the Civic Center, the rotating light helped define the city’s skyline during an era when illuminated landmarks were still uncommon. The imagery reinforced Los Angeles’s identity as a city linked to aviation and modern technology. |

| (1936)* - The Lindbergh Beacon atop Los Angeles City Hall illuminated as power from Hoover Dam first reached the city. |

| Historical Notes

The lighting of the Lindbergh Beacon in 1936 coincided with a major milestone in Los Angeles’s development: access to large scale, reliable hydroelectric power from Hoover Dam. The moment symbolized the city’s connection to one of the most ambitious engineering projects of the twentieth century and reinforced City Hall’s role as a visual symbol of civic pride and technological progress. As air traffic increased in the late 1930s, aviation authorities raised concerns that the powerful rotating beacon could be mistaken for an airport navigational light. Guidance from the Federal Aviation Administration and its predecessor agencies led to restrictions on the beacon’s operation, and by the early 1940s its regular use had largely ceased. Its brief period of prominence reflects how quickly aviation safety standards and navigational practices were evolving. |

City Hall in Daily Use

|

|

| (ca. 1929)* - View looking northwest showing an airplane, identified as a Fokker F.10, flying over Los Angeles City Hall. |

| Historical Notes

This image captures City Hall as part of everyday life in a rapidly modernizing city. Airplanes passing overhead were no longer novelties but symbols of Los Angeles’s growing role in aviation and transportation. The presence of City Hall beneath the aircraft reinforces the connection between local government and the technological future the city was embracing. Scenes like this showed that City Hall was not isolated from daily activity. It stood at the center of a city increasingly shaped by mobility, innovation, and speed. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)* – Postcard view showing Los Angeles City Hall with Spring Street in the foreground. |

| Historical Notes

Postcards such as this helped normalize City Hall as a familiar part of daily urban life. No longer a new landmark, the building had become a standard reference point for downtown Los Angeles. Street traffic, pedestrians, and nearby commercial buildings filled the scene, emphasizing City Hall’s role as a functioning center of government rather than a ceremonial backdrop. By the late 1930s, the building had settled into its long term role as the city’s administrative heart. |

|

|

| (1934)* – View looking northeast toward City Hall from the intersection of Spring and 1st Street. |

| Historical Notes

This street level view shows City Hall integrated into the everyday flow of downtown. Automobiles, pedestrians, and street activity dominate the foreground, while the tower rises steadily behind them. The contrast highlights how the building was designed to project authority without interrupting daily life below. City Hall’s visibility from multiple streets made it a constant presence for those who worked, shopped, or passed through downtown Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1949)* – Reporter taking a picture from the top of a “Radio Flash Car” parked on Bunker Hill with City Hall and the California State Building in the background. |

| Historical Notes

The Los Angeles Herald-Express “Radio Flash Car” represents mid-century news gathering at its most resourceful. Equipped with a radio telephone and a rooftop platform for photographers, the vehicle allowed reporters to transmit stories quickly from the field. City Hall’s presence in the background underscores its importance as a frequent subject of breaking news. Political decisions, public events, and civic debates often centered there, making it a natural focal point for journalists chasing the latest story. |

|

|

| (1950)* – View looking southwest toward the intersection of Los Angeles Street and Commercial Street, with City Hall in the background. Photo by Arnold Hylen. |

| Historical Notes

This image places City Hall within a dense mix of small scale commercial buildings, restaurants, and hotels. The contrast between the monumental tower and the modest foreground structures reflects the layered character of downtown Los Angeles in the mid twentieth century. Rather than dominating daily life, City Hall functioned as a steady backdrop, overseeing a city that continued to grow and change around it. |

|

|

| (1959)* - Street view looking south on Main Street showing City Hall at the southwest corner of Temple and Main streets. The Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office Building is seen on the right. |

| Historical Notes

By the late 1950s, City Hall had become a familiar and enduring feature of downtown. The surrounding streetscape shows how government buildings, transportation corridors, and everyday commerce coexisted within the Civic Center area. The presence of the multi globe streetlight in the foreground reflects earlier street lighting traditions that once defined downtown Los Angeles. Together, the elements in this scene illustrate how City Hall remained constant even as the city’s infrastructure and streets evolved. |

City Hall and the Civic Center

|

|

| (ca. 1930s)* - View of Los Angeles City Hall facing north from First Street. To the west on Spring Street are the old State Building, Hall of Records, and Hall of Justice. |

| Historical Notes

This view shows City Hall as the anchor of a growing Civic Center district. Rather than standing alone, the building was intentionally placed among county and state institutions to form a centralized seat of government. The surrounding structures reflect an effort to organize civic functions within a formal and orderly setting. The arrangement marked a shift away from the scattered government offices of earlier decades toward a planned civic core designed to convey stability, authority, and permanence. |

|

|

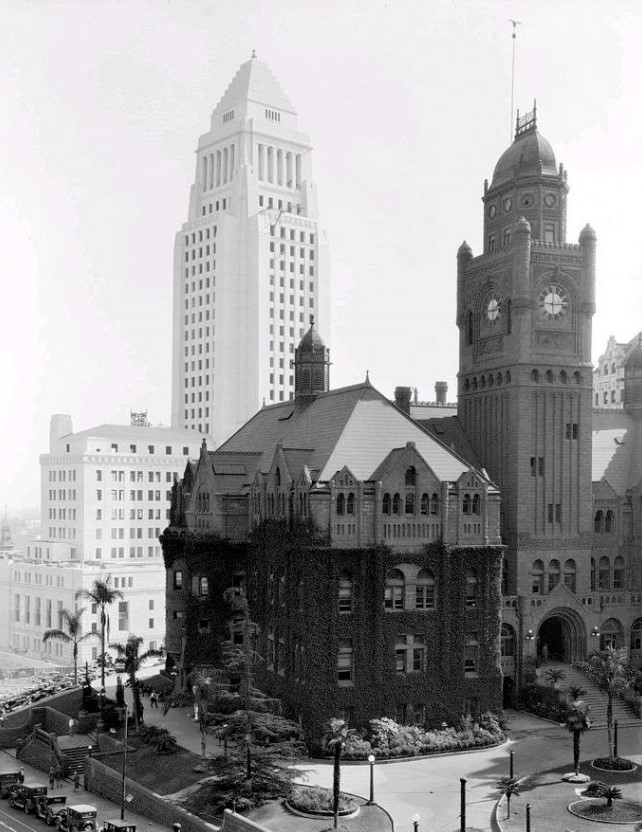

| (1930)* - View looking southeast at the intersection of Temple and Broadway. The County Courthouse stands at center with the Hall of Records to its right. City Hall towers above both in the background. |

| Historical Notes

This image highlights the layered development of the Civic Center during the early twentieth century. Older government buildings occupied the foreground while the newly completed City Hall rose behind them, signaling a new hierarchy within the civic landscape. Although these buildings coexisted for a time, the image foreshadows change. The original Los Angeles County Courthouse was demolished in 1936, and the Hall of Records remained standing until 1973, reflecting evolving ideas about government space and architectural preservation. |

|

|

| (1928)* – Newly opened City Hall towers over the old Los Angeles County Courthouse. Note the three level enclosed passageway between the Courthouse and the Hall of Records on the right. |

| Historical Notes

At the time City Hall opened, the Civic Center was a mix of old and new. The enclosed passageway connecting the County Courthouse and Hall of Records reflects earlier design priorities focused on functional efficiency rather than monumentality. City Hall’s scale and placement immediately altered this balance. Its height and visibility established it as the dominant civic structure, setting the direction for future redevelopment in the area. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)* - View showing City Hall in the background and the Los Angeles County Courthouse in the foreground. |

| Historical Notes

This image captures a transitional moment in downtown Los Angeles. The older courthouse, once a symbol of civic authority, now appears secondary to City Hall behind it. The contrast illustrates how quickly civic identity can shift as cities grow and redefine their priorities. Within a few years, the courthouse would be removed, making way for a reimagined Civic Center centered more clearly around City Hall. |

|

|

| (ca. 1930)* - Same view, image enhancement and colorization by Richard Holoff. |

| Historical Notes

The enhanced view brings renewed clarity to the architectural contrast between the two buildings. City Hall’s clean lines and vertical emphasis stand apart from the heavier, older forms of the courthouse. Seen together, the buildings reflect competing eras of civic design, one focused on tradition and the other on projecting a modern civic image. |

|

|

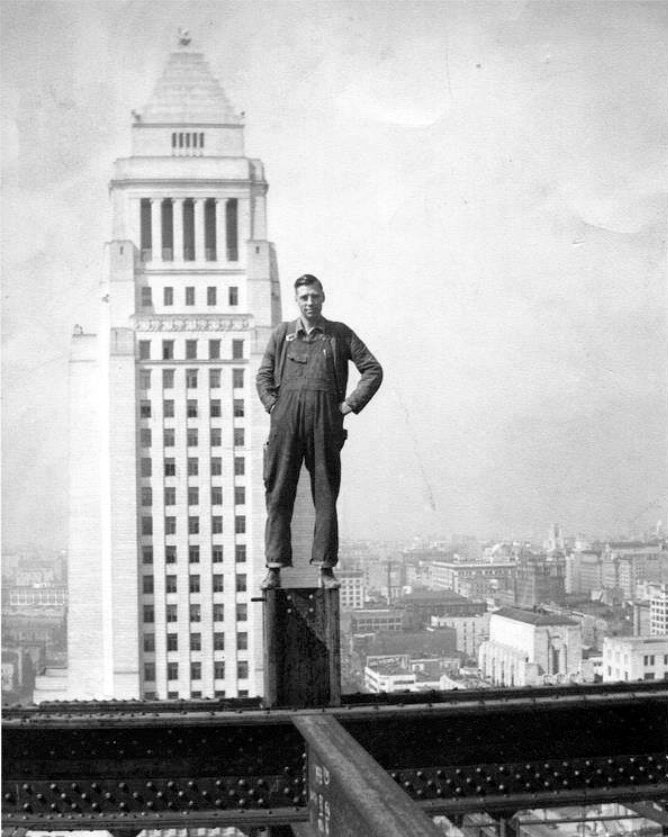

| (ca. 1938)* - View looking south toward City Hall showing a man standing atop steel framing for the new Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office Building. Photo courtesy of Lauren Frobisher Scanlon. Frank McGuire is seen in the image. |

| Historical Notes

This photograph documents the continued expansion of the Civic Center into the late 1930s. The Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office Building, completed in 1940, represented the federal government’s growing presence alongside city and county institutions. The worker standing atop the steel framing emphasizes both the scale of the project and the human effort behind the Civic Center’s construction. City Hall remains visible in the background, reinforcing its role as the visual and symbolic anchor of the district. |

City Hall and a Changing City

|

|

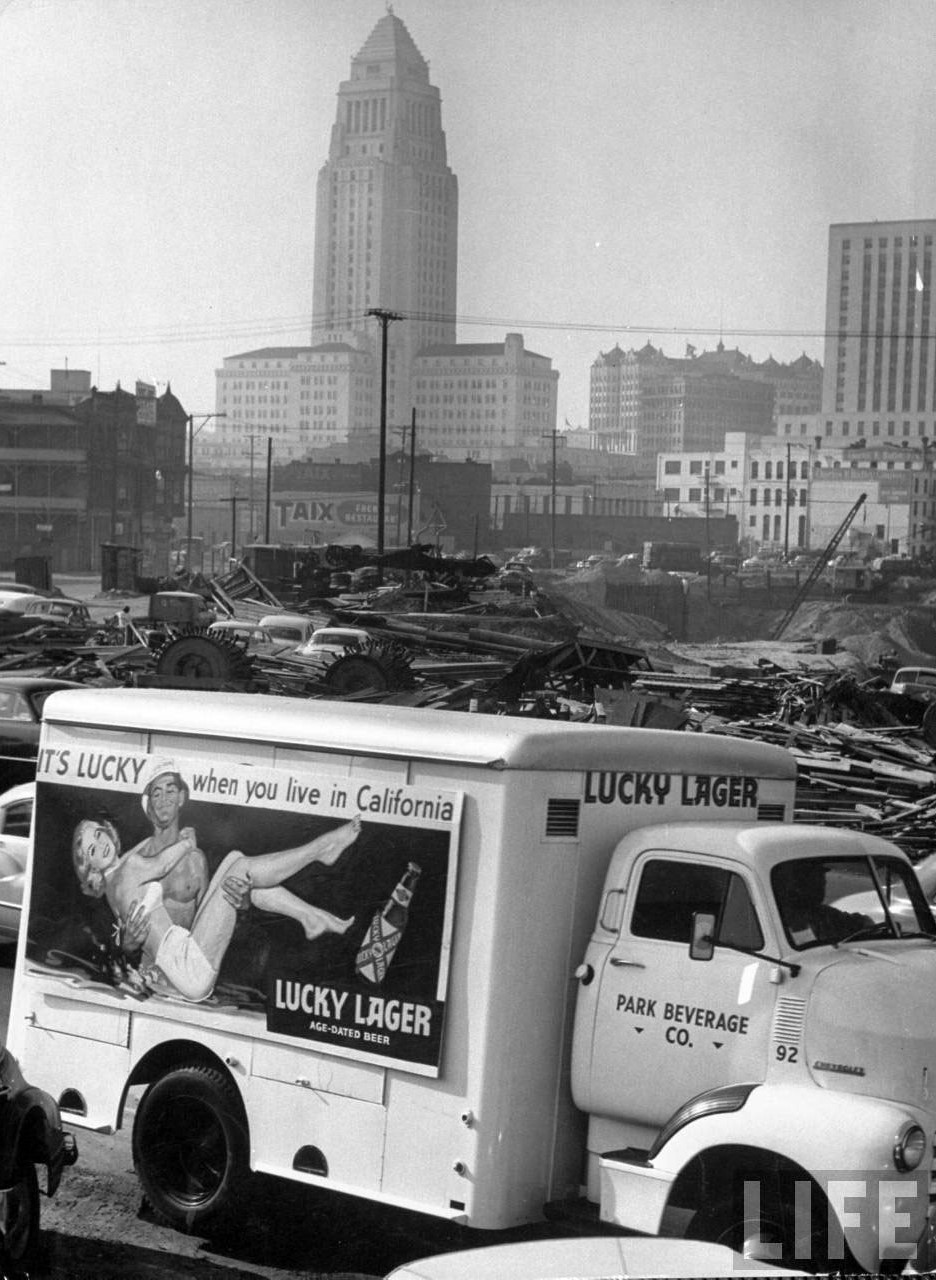

| (1953)* – View looking southwest toward Los Angeles City Hall from the site of the Aliso Street Project of the Santa Ana Freeway. Also visible from left to right are Taix French Restaurant, the old Hall of Records, and the Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office Building. |

| Historical Notes

This view captures downtown Los Angeles during a period of rapid physical transformation. Freeway construction pushed directly through established neighborhoods, reshaping the city around automobile travel. From the Santa Ana Freeway construction site, City Hall appears steady and unchanged, while the city around it is being dismantled and rebuilt. Although freeways promised faster movement and economic growth, they also brought more vehicles, increased emissions, and rising environmental costs. This image shows City Hall presiding over a city entering a new phase of development, one defined as much by infrastructure as by architecture. |

|

|

| (1954)* – Blimp flying over downtown Los Angeles on a smoggy day. Buildings visible include the Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office Building, the International Bank Building, and City Hall. |

| Historical Notes

By the early 1950s, air pollution had become one of Los Angeles’s most serious public health concerns. On September 9, 1954, a U.S. Navy blimp flew over downtown to collect air samples at multiple altitudes, including 500 feet, 1,000 feet, and the top of the smog layer. The flight marked a shift from speculation to scientific investigation. These tests supported the work of researchers such as Arie Haagen-Smit, whose studies helped identify the chemical causes of smog. City Hall’s presence beneath the blimp underscores how environmental challenges had become matters of public policy and governance, not just inconvenience. |

|

|

| (1954)* - Navy blimp testing air pollution levels as it passes City Hall through dense smog surrounding downtown Los Angeles. |

| Historical Notes

By the mid 1950s, city and county officials recognized that smog could not be addressed through guesswork or isolated enforcement. Scientific measurement became central to decision making, and air quality monitoring expanded across the region. Flights like this demonstrated that smog was layered, widespread, and regional in nature. These findings pushed policymakers away from blaming individual factories and toward coordinated solutions involving transportation, industry, and land use across Southern California. |

|

|

| (1954)* - Navy blimp passing City Hall through downtown smog. AI enhanced and colorized. |

| Historical Notes

This enhanced image reinforces how deeply smog shaped everyday life in mid century Los Angeles. City Hall, once introduced as a symbol of optimism and progress, now stood amid the unintended consequences of growth. Rather than diminishing City Hall’s importance, these challenges expanded its role. The building became the setting for debates over air quality, transportation policy, and regional planning, reflecting a city forced to confront the costs of its own success. |

The Lindbergh Beacon Afterward

|

|

| (1951)* - The rotating Lindbergh Beacon is visible atop Los Angeles City Hall. A portion of Bunker Hill appears at lower left, with the old State Building at center right. |

| Historical Notes

The Lindbergh Beacon was installed atop City Hall in 1928 as part of the building’s opening celebrations. Originally emitting a powerful white light, the rotating beacon symbolized Los Angeles’s embrace of aviation, modern technology, and national achievement following Charles Lindbergh’s historic transatlantic flight the year before. Concerns about air safety soon followed as aviation traffic increased over the city. In 1931, the U.S. Department of Commerce determined that the bright white beacon posed a potential hazard to pilots, and the light was changed to red. During World War II, the beacon was turned off as part of regional blackout precautions intended to protect coastal cities. Although the beacon was relit on limited occasions in the postwar years, it was no longer used regularly after the early 1940s. The structure itself remained in place until the early 1950s, when the beacon was removed, marking the end of its original role as both a navigational aid and a symbolic feature of Los Angeles City Hall. |

Inside City Hall

|

|

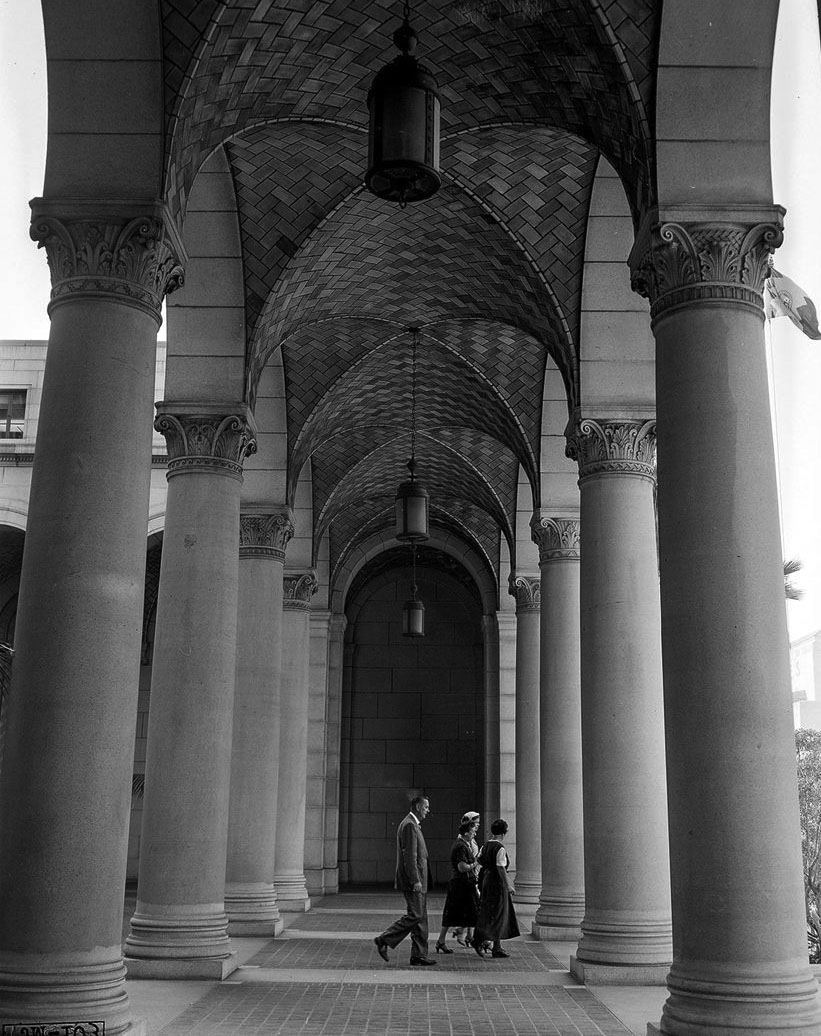

| (1955)* - Spring Street entrance to Los Angeles City Hall. This image led off the Know Your City photography series in the November 18, 1955, Los Angeles Times. |

| Historical Notes

The Spring Street entrance served as one of the primary public access points to City Hall. Its formal design reflected the building’s role as an open seat of government, welcoming residents who came to conduct city business or attend public meetings. The Know Your City series was intended to familiarize readers with civic spaces they might otherwise never enter. Featuring City Hall emphasized its importance not just as a landmark, but as a place meant to be used by the public. |

|

|

| (1950s)* – View showing the steps to City Hall on the Spring Street side. |

| Historical Notes

These steps functioned as both an architectural threshold and a daily gathering space. City employees, elected officials, visitors, and residents moved through this entrance throughout the day, reflecting City Hall’s role as a working building rather than a ceremonial monument. The steady flow of foot traffic illustrates how City Hall had become woven into the routine life of downtown Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (1955)* – View showing the south corridor on the Spring Street floor of City Hall as seen from the rotunda. At the end, the Mayor’s office is on the left and City Council offices on the right. A bronze plaque is set into the rotunda floor. |

| Historical Notes

This corridor shows how City Hall’s interior was organized around practical governance. Offices for elected officials were arranged along direct circulation routes, emphasizing accessibility and efficiency rather than formality. The bronze plaque embedded in the rotunda floor marked the space as civic ground, reinforcing the idea that this was a place where public business was conducted on behalf of the city’s residents. |

|

|

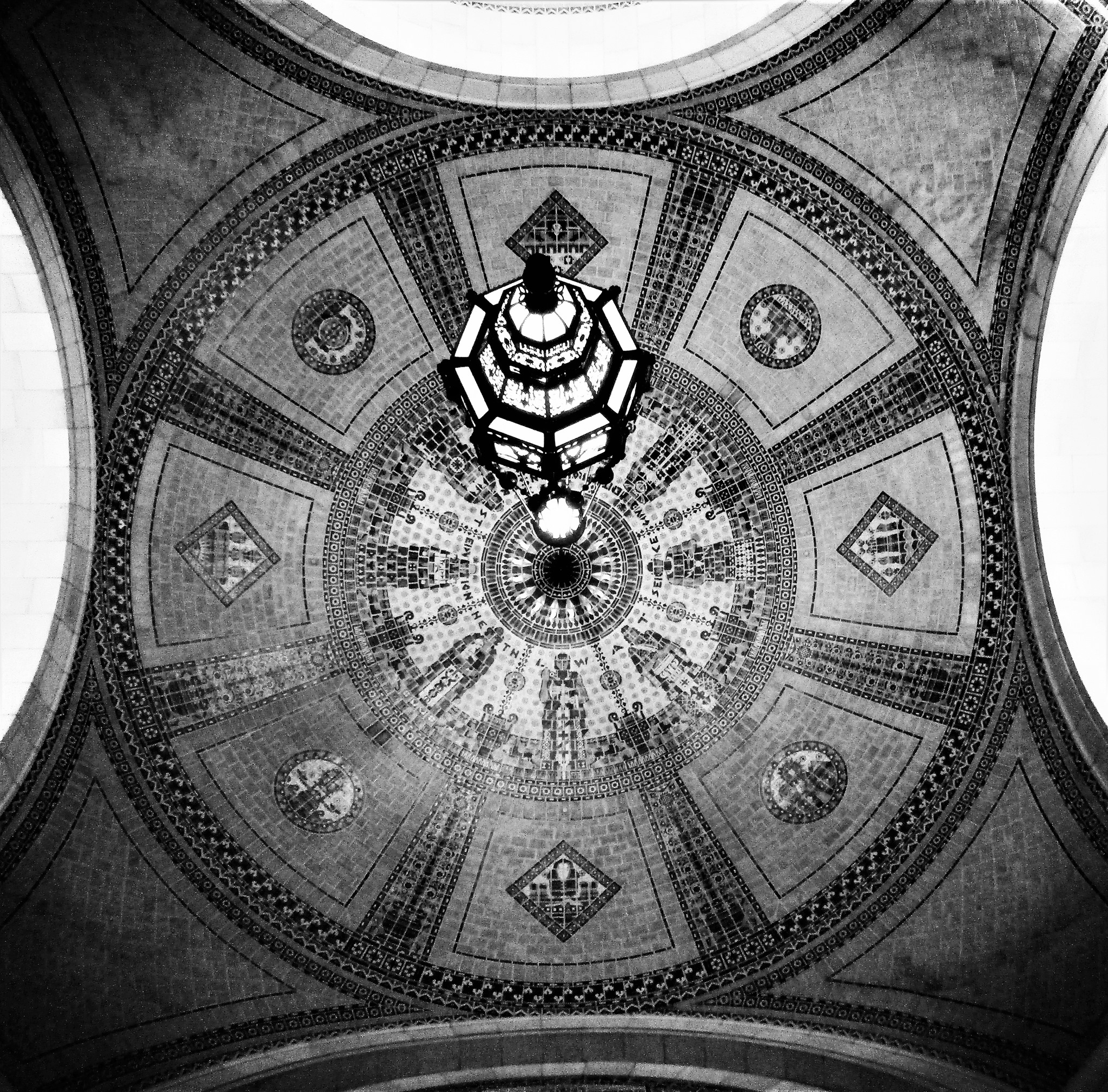

| (2021)* – Looking up at the ceiling of the City Hall rotunda on the third floor. Photo by Howard Gray. |

| Historical Notes

The interior of City Hall was designed by Austin Whittlesey, whose work emphasized grandeur without excess. Byzantine in style, the interior features vaulted ceilings, marble floors, and an expansive rotunda rising high above the main floor. The rotunda remains the building’s most dramatic interior space. Its scale, decorative details, and lighting were intended to inspire respect for civic institutions while providing a dignified setting for public life. Even decades after its completion, the space continues to communicate the ideals of permanence, order, and public service that defined City Hall’s original purpose. |

City Hall on the Modern Skyline

|

|

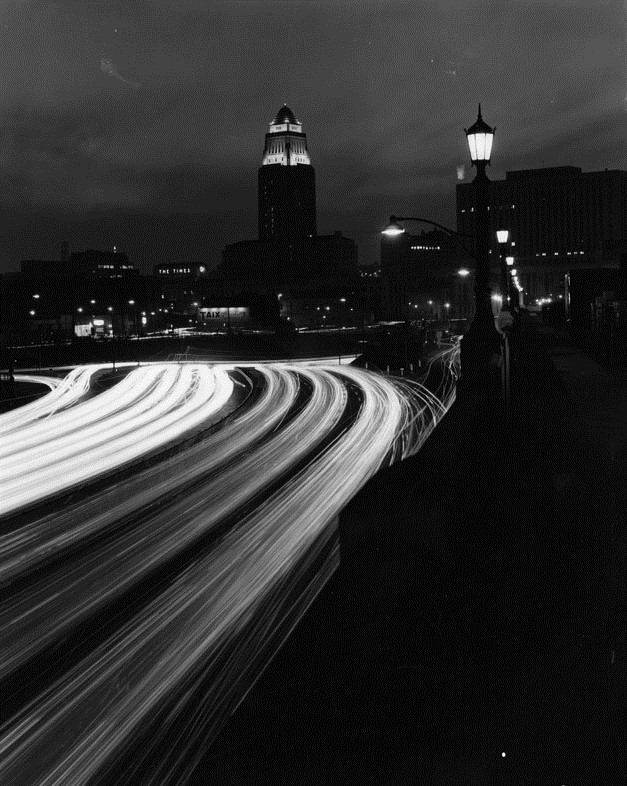

| (1962)* - Night view looking southwest toward Los Angeles City Hall, with Union Station visible at right and the Hollywood Freeway (U.S. 101) in the foreground. |

| Historical Notes

This nighttime view looks southwest toward Los Angeles City Hall, with Union Station visible in the foreground. Completed in 1939, Union Station had become the city’s primary rail gateway by the time this photograph was taken, anchoring downtown’s northeastern edge and linking Los Angeles to regional and national rail networks. The presence of the Hollywood Freeway alongside Union Station reflects the coexistence of older rail-based transportation and the automobile-oriented infrastructure that increasingly defined the city after World War II. City Hall remains prominent in the distance, serving as a steady civic reference point amid changing transportation patterns, expanding freeway networks, and a rapidly evolving urban landscape. |

|

|

| (1969)* – Night view looking northeast over the Los Angeles Times Building toward City Hall. |

| Historical Notes

By the late 1960s, downtown Los Angeles glowed with artificial light. Office towers, street lighting, signage, and traffic combined to create an active nighttime environment. City Hall remained prominent, but no longer singular. This image captures a city whose identity was expanding vertically and outward. City Hall continued to serve as a visual anchor, even as the skyline grew denser and more layered around it. |

|

|

| (2013)* - View looking northeast showing Los Angeles City Hall at sunset. Photo by Michael J. Fromholtz. |

| Historical Notes

Although surrounded by taller buildings, City Hall remains one of the most recognizable structures in Los Angeles. Its form, proportions, and placement continue to distinguish it from the glass and steel towers that followed. Between 1998 and 2001, the building underwent a major seismic retrofit designed to allow it to remain functional after a magnitude 8.2 earthquake. In 1976, Los Angeles City Hall was designated Historic-Cultural Monument No. 150, recognizing its architectural and civic significance. |

|

|

| (2013)* – City Hall in perspective. View looking northeast with downtown Los Angeles and the snow-capped San Gabriel Mountains in the background. Photo by Todd Jones. |

| Historical Notes

Once the tallest building in Los Angeles for more than three decades, City Hall is now dwarfed by dozens of skyscrapers. The city experienced a major building boom from the early 1960s through the early 1990s, during which most of its tallest structures were completed. Despite this dramatic change, City Hall retains a distinct presence. Rather than competing in height, it stands as a reminder of an earlier vision of civic identity, when symbolism, proportion, and permanence mattered as much as scale. |

Closing Perspective

Across nearly a century of growth, reinvention, and expansion, Los Angeles City Hall has remained constant while the city around it transformed repeatedly. Once a declaration of arrival, it now serves as a point of continuity, linking generations to a shared civic center. Its lasting importance lies not in how tall it is, but in how long it has endured, continuing to represent public service, civic responsibility, and the evolving story of Los Angeles itself. |

* * * * * |

|

Other Sections of Interest |

|

Water and Power in Early LA |

|

Newest Additions |

New Search Index |

A new SEARCH INDEX has been added to help navigate through the thousands of topics and images found in our collection. Try it out for a test run.

Click HERE for Search Index |

* * * * * |

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index

© Copyright Water and Power Associates

Layout by Rocket Website Templates